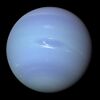

Astronomy:Naiad (moon)

Naiad as seen by Voyager 2 (elongation is due to smearing) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Voyager Imaging Team |

| Discovery date | September 1989 |

| Designations | |

Designation | Neptune III |

| Pronunciation | /ˈneɪəd/ or /ˈnaɪæd/,[1][2] /ˈneɪəd/ or /ˈnaɪəd/[3] |

| Named after | pl. Ναϊάδες Nāïades |

| Adjectives | Naiadian /-ˈædiən/[4] |

| Orbital characteristics[5][6] | |

| Epoch 18 August 1989 | |

| 48 224.41 km | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0047 ± 0.0018 |

| Orbital period | 0.2943958 ± 0.0000002 d |

| Inclination |

|

| Satellite of | Neptune |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Dimensions | 96×60×52 km[7][8] |

| Mean radius | 30.2 ± 3.2 km[6] |

| Mean density | 0.8±0.48 g/cm3[9] |

| Rotation period | synchronous |

| Axial tilt | zero |

| Albedo | 0.072[7][10] |

| Physics | ~51 K mean (estimate) |

| Apparent magnitude | 23.91[10] |

Naiad /ˈneɪəd/, (also known as Neptune III and previously designated as S/1989 N 6) named after the naiads of Greek legend,[11] is the innermost satellite of Neptune and the nearest to the center of any gas giant with moons with a distance of 48,224 km from the planet's center. Its orbital period is less than a Neptunian day, resulting in tidal dissipation that will cause its orbit to decay. Eventually it will either crash into Neptune's atmosphere or break up to become a new ring.[12]

History

Naiad was discovered sometime before mid-September 1989 from the images taken by the Voyager 2 probe. The last moon to be discovered during the flyby, it was designated S/1989 N 6.[13] The discovery was announced on 29 September 1989, in the IAU Circular No. 4867, and mentions "25 frames taken over 11 days", implying a discovery date of sometime before 18 September. The name was given on 16 September 1991.[14]

Physical characteristics

Naiad is irregularly shaped. It is likely that it is a rubble pile re-accreted from fragments of Neptune's original satellites, which were smashed up by perturbations from Triton soon after that moon's capture into a very eccentric initial orbit.[15]

Orbit

Naiad is in a 73:69 orbital resonance with the next outward moon, Thalassa, in a "dance of avoidance". As it orbits Neptune, the more inclined Naiad successively passes Thalassa twice from above and then twice from below, in a cycle that repeats every ~21.5 Earth days. The two moons are about 3540 km apart when they pass each other. Although their orbital radii differ by only 1850 km, Naiad swings ~2800 km above or below Thalassa's orbital plane at closest approach. Thus this resonance, like many such orbital correlations, serves to stabilize the orbits by maximizing separation at conjunction. However, the role of orbital inclination in maintaining this avoidance in a case where eccentricities are minimal is unusual.[16][9]

Exploration

Since the Voyager 2 flyby, the Neptune system has been extensively studied from ground-based observatories and the Hubble Space Telescope as well. In 2002–03 the Keck telescope observed the system using adaptive optics and detected easily the largest four inner satellites. Thalassa was found with some image processing, but Naiad was not located.[17] Hubble has the ability to detect all the known satellites and possible new satellites even dimmer than those found by Voyager 2. On 8 October 2013 the SETI Institute announced that Naiad had been located in archived Hubble imagery from 2004.[18] The suspicion that the loss of positioning was due to considerable errors in Naiad's ephemeris[19] proved correct as Naiad was ultimately located 80 degrees from its expected position.

References

- ↑ Noah Webster (1884) A Practical Dictionary of the English Language

- ↑ naiad (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, September 2005, http://oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=naiad (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "Naiad". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/naiad.

- ↑ Morris (1904) British violin-makers

- ↑ Jacobson, R. A.; Owen, W. M. Jr. (2004). "The orbits of the inner Neptunian satellites from Voyager, Earthbased, and Hubble Space Telescope observations". Astronomical Journal 128 (3): 1412–1417. doi:10.1086/423037. Bibcode: 2004AJ....128.1412J.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Showalter, M. R.; de Pater, I.; Lissauer, J. J.; French, R. S. (2019). "The seventh inner moon of Neptune". Nature 566 (7744): 350–353. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-0909-9. PMID 30787452. PMC 6424524. Bibcode: 2019Natur.566..350S. https://www.spacetelescope.org/static/archives/releases/science_papers/heic1904/heic1904a.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Karkoschka, E. (2003). "Sizes, shapes, and albedos of the inner satellites of Neptune". Icarus 162 (2): 400–407. doi:10.1016/S0019-1035(03)00002-2. Bibcode: 2003Icar..162..400K.

- ↑ Williams, D. R. (2008-01-22). "Neptunian Satellite Fact Sheet". NASA (National Space Science Data Center). http://nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov/planetary/factsheet/neptuniansatfact.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brozović, M.; Showalter, M. R.; Jacobson, R. A.; French, R. S.; Lissauer, J. J.; de Pater, I. (October 31, 2019). "Orbits and resonances of the regular moons of Neptune". Icarus 338 (2): 113462. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2019.113462. Bibcode: 2020Icar..33813462B.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "Planetary Satellite Physical Parameters". JPL (Solar System Dynamics). 2008-10-24. http://ssd.jpl.nasa.gov/?sat_phys_par.

- ↑ "Planet and Satellite Names and Discoverers". Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature. USGS Astrogeology. July 21, 2006. http://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/append7.html.

- ↑ "Naiad". NASA. https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/moons/neptune-moons/naiad/in-depth/.

- ↑ Green, D. W. E. (September 29, 1989). "Neptune". IAU Circular 4867. http://www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu/iauc/04800/04867.html. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ Marsden, B. G. (September 16, 1991). "Satellites of Saturn and Neptune". IAU Circular 5347. http://www.cbat.eps.harvard.edu/iauc/05300/05347.html. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ↑ Banfield, D.; Murray, N. (October 1992). "A dynamical history of the inner Neptunian satellites". Icarus 99 (2): 390–401. doi:10.1016/0019-1035(92)90155-Z. Bibcode: 1992Icar...99..390B.

- ↑ "NASA Finds Neptune Moons Locked in 'Dance of Avoidance'". November 14, 2019. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=7540.

- ↑ Marchis, F.; Urata, R.; de Pater, I.; Gibbard, S.; Hammel, H. B.; Berthier, J. (May 2004). "Neptunian Satellites observed with Keck AO system". 36. p. 860. Bibcode: 2004DDA....35.0708M.

- ↑ "Lost Neptune Moon Re-Discovered". http://news.discovery.com/space/astronomy/lost-neptune-moon-found-131008.htm.

- ↑ Showalter, M. R.; Lissauer, J. J.; de Pater, I. (August 2005). "The Rings of Neptune and Uranus in the Hubble Space Telescope". 37. p. 772. Bibcode: 2005DPS....37.6609S.

External links

- Naiad Profile by NASA's Solar System Exploration

- Neptune's Known Satellites (by Scott S. Sheppard)

- Archival Hubble Images Reveal Neptune's "Lost" Inner Moon (SETI : October 8, 2013)

- Neptune Moon Dance (animation) on YouTube from NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory

|