Medicine:Timeline of Chagas disease

From HandWiki

This is a timeline of Chagas disease, describing major events such as scientific and medical developments, as well as major organizations and campaigns aimed at combating the disease.

| Year/period | Key developments |

|---|---|

| 16th century onwards | Upon the arrival of the Spanish in South America, several accounts by travellers and physicians describing patients with chagas disease–like symptoms merge.[1] |

| 1920s–1930s | Salvador Mazza and others detect some 1,400 cases of Chagas disease in the Argentine Gran Chaco in these decades, in a region where others have failed to identify a case in previous decades.[2] |

| 1940s | Introduction of serodiagnostic tests shows that infections with Chagas disease causative parasite trypanosoma cruzi are widespread in Latin America.[1] |

| 1950s | Chagas disease prevention programs start to be conducted.[2] In Central America, the presence of Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus is recognized as a public health problem.[3] |

| 1980s–1990s | Chagas disease prevention is dramatically improved through large-scale vector control and screening of blood donors.[2] The estimated burden of disease in terms of disability-adjusted life years declines from 2·7 million in 1990 to 586,000 in 2001 in the Southern Cone.[4] |

| Recent years | Due to migration of people infected with Chagas disease causing parasite trypanosoma cruzi from endemic countries, Chagas disease is increasingly becoming a global health problem. At present about 7-8 million people are estimated to be infected with Chagas disease causing parasite trypanosoma cruzi, mostly in Latin America, and more than 25 million people are at risk of contracting Chagas disease. In 2008 alone, over 10,000 deaths from Chagas disease were reported.[1][2] |

Full timeline

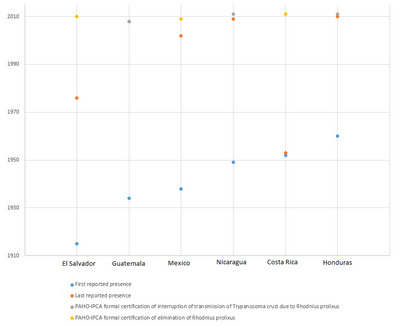

First and last reported presence of Chagas disease vector rhodnius prolixus in Central America and Mexico.[3]

Estimated Nuber of immigrants infected with trypanosoma cruzi in European countries.[5]

| Year/period | Type of event | Event | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 7–10 million BP | The ancestor of Chagas disease parasite trypanosoma cruzi is probably introduced to South America via bats.[1] | South America | |

| ~15000 BP | Infection | Chagas parasite trypanosoma cruzi starts to affect human beings upon their arrival in the Americas.[1] | Americas |

| ~9000 BP | Infection | The earliest detection of a chagas parasite trypanosoma cruzi infection in a human comes from a Chinchorro mummy. Chagas disease causative parasite trypanosoma cruzi infections would also be found in mummies of subsequent cultures that succeeded the Chinchorros and were living in the same area up to the time of the Spanish conquest in the 16th century.[1] | South America |

| 1707 | Medical development | Portuguese physician Miguel Diaz Pimenta publishes book first suggesting clinical report relating to possible intestinal symptoms of Chagas disease. Pimenta describes a condition, which is known as “bicho”, “that causes the humours to be retained, causing the patient to have little desire to eat”.[1] | |

| 1735 | Medical development | Portuguese physician, Luís Gomes Ferreira describes account on the megavisceral syndrome of Chagas disease.[1] | |

| 1835 | Report | During The Voyage of the Beagle, British naturalist Charles Darwin writes account of blood sucking process of a triatomine bug (known as benchuca or the great black bug of the Pampas) attacking on him. Based on this encounter and Darwin's prolonged gastric and nervous symptoms, it would be hypothesised that Darwin was suffering from Chagas disease later in his life. Despite all this, the critical role of triatomine bugs in transmitting Chagas disease would remain undiscovered until 1909.[1][4] | Argentina |

| 1873 | Medical development | Danish physician Theodoro Langgaard describes Chagas disease as “mal de engasgo” probably referring to dysphagia.[1][6] | Brazil |

| 1909 | Scientific development | Brazilian scientist Carlos Chagas, after years of researching trypanosomes, finds the relation between these pathogenes and a feverish two-year-old girl with enlarged spleen and liver and swollen lymph nodes. Chagas discovers a new human disease which soon would bear his name.[7][1][8] | Brazil |

| 1913 | Scientific development | Nattan-Larrier reports finding Chagas disease causing parasite trypanosoma cruzi in the milk of laboratory animals.[9] | |

| 1915 | Scientific development | Rhodnius prolixus, one of the main vectors of trypanosoma cruzi (causative agent of Chagas disease) in Central America, is discovered in El Salvador.[3] | El Salvador |

| 1930–1939 | Scientific development | Argentine epidemiologist Salvador Mazza describes more than a thousand Chagas disease cases in the Argentine Chaco province. Mazza is the first to raise the possibility that Chagas disease could be transmitted by blood transfusion.[1] | Argentina |

| 1934 | Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus, is first reported in Guatemala.[3] | Guatemala | |

| 1936 | Scientific development | Study reports having found trypomastigotes in the milk of mothers in the acute phase of Chagas disease.[9] | |

| 1939 | Scientific development | Swiss chemist discovers Organochloride DDT's insecticidal properties.[10] This would allow vector control in the 1940s when the first organochlorine insecticides are developed.[1] | |

| 1947 | Prevention development | Gamma-hexachlorocyclohexane (BHC) insecticide is released and recommended for its use as first control alternative against Chagas disease vectors. For many years ahead, BHC would remain the mainstay of Chagas disease vector control trials and campaigns.[4] | |

| 1949 | Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus, is first reported in Nicaragua.[3] | Nicaragua | |

| 1953 | Medical development | Dye crystal violet is found to kill Chagas disease parasite trypanosoma cruzi in blood preservations. Since then the dye would be widely employed in blood banks in endemic areas to eliminate the parasite from blood used for transfusion.[1] | |

| 1953 | Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus, is first reported in Costa Rica.[3] | Costa Rica | |

| 1956–1959 | Chagas disease vector Rhodnius prolixus, is first reported in Honduras.[3] | Honduras | |

| 1966 | Medical development | Swiss multinational health-care company Hoffmann-La Roche introduces benznidazole for treatment of Chagas disease.[1] | Switzerland |

| 1970 | Medical development | German multinational company Bayer introduces Nifurtimox for treatment of Chagas disease. | Germany |

| 1972 | Scientific development | M. A. Miles detects trypomastigotes and antibodies against Chagas disease parasite trypanosoma cruzi, after examining the milk of mice in the acute phase of the disease. Finally, Miles would conclude that, experimentally, even in the acute phase of the disease, Chagas transmission through breast-feeding is rare.[9] | |

| 1975 | Program launch | Brazil starts operating Chagas disease control program. At the time, 711 out of over 5000 municipalities have triatomine-infested houses targeted by the program.[4] | Brazil |

| 1975–1978 | Program launch | The Ministry of Health of Brazil conducts a seroprevalence survey in its Chagas disease endemic areas and finds 4.1% individuals positive, equivalent to about 800,000 cases of the disease.[4] | Brazil |

| 1983 | Program launch | Brazil launches national campaign of Chagas disease vector control. By 1986 75% of the initial objectives would be attained.[4] | Brazil |

| 1986 | Report | Brazil reports 186 municipalities infested with triatomines (potential Chagas disease vectors).[4] | Brazil |

| 1991 | Program launch | A Southern Cone Initiative (INCOSUR), a regional intergovernmental control program agreed between the governments of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, Uruguay and Peru, is launched with the original objectives of eliminating all domestic and peridomestic populations of the main vector triatoma infestans and transmission of trypanosoma cruzi via blood transfusion in the Southern Cone countries by the year 2000.[7][2][4][11] | Argentina , Bolivia, Brazil , Chile , Paraguay, Uruguay, Peru |

| 1993 | Report | Brazil reports 83 municipalities infested with triatomines (potential Chagas disease vectors).[4] | Brazil |

| 1997 | Eradication | Control over the transmission of Chagas disease infection by vector triatoma infestans is certified in Uruguay by the Pan American Health Organization.[7][11] | Uruguay |

| 1997 | Program launch | The Initiative of the Andean Countries (IAC) is launched by Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela with the purpose of interrupting transmission via vector and transfusion of Chagas disease in the region.[7][12] | Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, Venezuela |

| 1997 | Program launch | The Initiative of Central America and Mexico is launched with the objectives of interrupting the transmission of Chagas disease by vector rhodnius prolixus, reducing domestic infestation by vector triatoma dimidiata and interrupting parasite trypanosoma cruzi transmission through blood transfusion.[7][3] | |

| 1998 | Program launch | The World Health Assembly and others set target for interruprion of transmission of Chagas disease by 2005 (not achieved).[2] | |

| 1999 | Eradication | Control over the transmission of Chagas disease infection by vector triatoma infestans is certified in Chile by the Pan American Health Organization.[7][11] | Chile |

| 2002 | Report | The burden of Chagas disease in Latin America is calculated to amount to as much as 2.7 times the joint burden of malaria, schistosomiasis, leishmaniasis and leprosy, and accounts for 670 000 disability-adjusted life years through its impact on worker productivity, premature disability and death.[2] | Latin America |

| 2002 | Organization | The Initiative of the Amazon Countries (AMCHA) is organized by the Pan American Health Organization with the objectives of evaluating the risks of Chagas endemicity becoming established in the Amazon Region, identifying the research required for monitoring and prevention of Chagas disease in the region, proposing monitoring and prevention, and proposing an international cooperation system. Nine Amazon countries are represented: Bolivia, Brazil , Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, French Guiana, Peru, Surinam and Venezuela.[7] | Brazil (Manaus) |

| 2006 | Eradication | Control over the transmission of Chagas disease infection by vector triatoma infestans is certified in Brazil by the Pan American Health Organization.[7][4] | Brazil |

| 2008 | Eradication | Guatemala becomes the first country in Central America to be formally certified as free of Chagas disease transmission due to rhodnius prolixus.[3][13] | Guatemala |

| 2011 | Eradication | All the previously endemic countries of Central America, in addition to Mexico, are formally certified as free of Chagas disease transmission due to their main domestic vector, rhodnius prolixus.[3] | Mexico, Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica |

See also

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 Steverding, Dietmar (2014). "The history of Chagas disease". Parasites & Vectors 7: 317. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-317. PMID 25011546.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Gürtler, Ricardo E; Diotaiuti, Liléia; Kitron, Uriel. Commentary: Chagas disease: 100 years since discovery and lessons for the future. https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/37/4/698/740634/Commentary-Chagas-disease-100-years-since. Retrieved 28 February 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Hashimoto, Ken; Schofield, Christopher J (2012). "Elimination of Rhodnius prolixus in Central America". Parasites & Vectors 5: 45. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-5-45. PMID 22357219.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 MASSAD, E. (2008). "The elimination of Chagas' disease from Brazil". Epidemiology and Infection 136 (9): 1153–1164. doi:10.1017/S0950268807009879. PMID 18053273.

- ↑ Steverding, Dietmar (2014). "The history of Chagas disease". Parasites & Vectors 7: 317. doi:10.1186/1756-3305-7-317. PMID 25011546.

- ↑ Marcondes de Rezende, Joffre (2009-01-01). À sombra do Plátano: crônicas de história da medicina. ISBN 9788561673635. https://books.google.com/?id=hJwnBgAAQBAJ&pg=PA308&lpg=PA308&dq=%22mal+de+engasgo%22+%22langaard%22#v=onepage&q=%22mal%20de%20engasgo%22%20%22langaard%22&f=false. Retrieved 8 February 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Rodrigues Coura, José; Albajar Viñas, Pedro; Junqueira, Angela (2014). "Ecoepidemiology, short history and control of Chagas disease in the endemic countries and the new challenge for non-endemic countries". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 109 (7): 856–862. doi:10.1590/0074-0276140236. PMID 25410988.

- ↑ Kropf, SP; Sá, MR (2009). "The discovery of Trypanosoma cruzi and Chagas disease (1908-1909): tropical medicine in Brazil.". Historia, Ciencias, Saude--Manguinhos 16 Suppl 1: 13–34. doi:10.1590/S0104-59702009000500002. PMID 20027916.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Norman, Francesca F.; López-Vélez, Rogelio (2013). "Chagas Disease and Breast-feeding". Emerging Infectious Diseases 19 (10): 1561–1566. doi:10.3201/eid1910.130203. PMID 24050257.

- ↑ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1948". Nobelprize. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1948/. Retrieved 16 December 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Rodrigues Coura, José (2013). "Chagas disease: control, elimination and eradication. Is it possible?". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 108 (8): 962–967. doi:10.1590/0074-0276130565. PMID 24402148.

- ↑ Guhl, F (2007). "Chagas disease in Andean countries.". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 102 Suppl 1: 29–38. doi:10.1590/S0074-02762007005000099. PMID 17891273.

- ↑ Trypanosomiasis—Advances in Research and Treatment: 2012 Edition. Scholarly Editions. 2012-12-26. ISBN 9781481608909. https://books.google.com/?id=e_LY1heZbkgC&pg=PT14&lpg=PT14&dq=%222008%22+%22guatemala%22+%22prolixus%22#v=onepage&q=%222008%22%20%22guatemala%22%20%22prolixus%22&f=false. Retrieved 2 March 2017.