Biology:Plant collecting

Plant collecting is the acquisition of plant specimens for the purposes of research, cultivation, or as a hobby. Plant specimens may be kept alive, but are more commonly dried and pressed to preserve the quality of the specimen. Plant collecting is an ancient practice with records of a Chinese botanist collecting roses over 5000 years ago.[1]

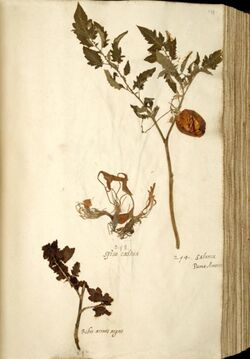

Herbaria are collections of preserved plants samples and their associated data for scientific purposes. The largest herbarium in the world exist at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, in Paris, France. Plant samples in herbaria typically include a reference sheet with information about the plant and details of collection. This detailed and organized system of filing provides horticulturist and other researchers alike with a way to find information about a certain plant, and a way to add new information to an existing plant sample file.

The collection of live plant specimens from the wild, sometimes referred to as plant hunting, is an activity that has occurred for centuries. The earliest recorded evidence of plant hunting was in 1495 BC when botanists were sent to Somalia to collect incense trees for Queen Hatshepsut. The Victorian era saw a surge in plant hunting activity as botanical adventurers explored the world to find exotic plants to bring home, often at considerable personal risk. These plants usually ended up in botanical gardens or the private gardens of wealthy collectors. Prolific plant hunters in this period included William Lobb and his brother Thomas Lobb, George Forrest, Joseph Hooker, Charles Maries and Robert Fortune. [2]

Plant pressing

Proper pressing and mounting techniques are critical to the longevity of a collected plant sample. Properly preserved plant samples can last for hundreds of years.[3] The New York Botanical Garden itself holds plant samples that date back to the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804–1806.

Sample gathering

The first step of plant pressing begins with the collection of the sample. When collecting a sample it is important to first make sure that land you are collecting on allows for the removal of natural specimens. The next step after finding a suitable plant for collection is to assign it with a number for record keeping purposes. This number system is up to the individual collector, but usually involves the date of collection or the sequential number of that collection. Along with an assigned number, observations about the plant's location and live appearance should be noted in detail. These field notes will accompany the finished sample to provide supplementary information about the plant.[4][5]

Compression

After cleaning the sample of any mud or dirt, the next step is to press the sample. Some samples may press better if they have been left to wilt for a few days. However plants should never be allowed to spoil or decompose before pressing, as this will impact the quality of the dried product. Plant presses are most commonly constructed with two flat smooth pieces of wood, and some type of compression mechanism. Compression may be accomplished with tightened nuts and bolts on the corners of the press, with tightened straps around the press, or by placing weights on top of the press. When placing in the press, plant samples should be sandwiched between a few layers of absorbent blotter. Newspaper and cardboard are two common choices for blotter material. When arranging the plant in the press it is important to remember that the dried plant product will be fragile and inflexible, so position the plant exactly as you wish the final product to appear. Tighten the press and wait approximately a day to check up on the plant. The blotter should be taken out and replaced with dry blotter roughly every 24 hours. Complete drying time will vary depending on the type of plant, but is generally 7–10 days. Fleshier plants such as succulents will take longer.[6][3][5]

Mounting

After the plant sample has been sufficiently dried and pressed, it must be mounted. The quality of mounting not only impacts the appearance of the plant sample, but also determines the rate of deterioration the sample will experience. Herbarium quality mounts use specialized paper for the best protection against deterioration.[7] This paper can either be 100% alpha cellulose paper or cotton “rag” paper. These types of paper are ideal for preserving plant samples because they are acid free and pH neutral. Samples can be strapped to the paper with linen tape, or glued onto the sheet. If glue is needed, it is recommended that Grade A methyl cellulose mixed with water be used for optimal deterioration resistance.[4]

Storage

In order for plant specimens to be kept in good condition for future reference, adequate storage conditions are needed. The storage space should be kept in a low light, low humidity environment. The temperature of the storage space should be kept cool, between 50 – 65 degrees Fahrenheit.[8]

It is important to keep the storage space free of harmful pest. It is recommended to protect the specimens by sheathing the sheets in sealed plastic bags. Various pesticides may also be used to protect the storage space from pest infestation. If pest infestation has already occurred, the samples should be frozen for three to four days. Freezing new additions of plant samples is a suggested preventative measure against the introduction of pest to the storage space.[7][4]

Collection of herbarium specimens

Herbarium specimens of plants are collected for a number of different uses. They can assist in accurate identification and provide a species record for a time and place that can be used in distribution maps. They can also provide biological material for researchers, a reference point to document scientific names and vouchers for research and seed collections.[9] DNA barcoding, a new method of identification of plant vouchers, is being used in herbaria across the world.[10] The Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History creates their barcodes from a short sequence of plant DNA, which can be easily identified from all healthy specimens of the species. This barcode is then printed and placed onto the plant mount. By creating these DNA barcodes, the process of organizing and loaning plant specimens becomes more streamlined and can be mechanized.

Voucher specimens

Voucher specimens are select herbarium specimens. What distinguishes these specimens from others is that a voucher specimen is a "representative sample of an expertly identified organism." These specimens are usually associated with a professional research article and are considered to be more official references than a typical herbarium specimen. Voucher specimens can be useful in many ways such as use for comparison when scientists think they have found a new species or when dichotomous keys have narrowed the possible species down to a few that have minute differences.[11]

Plant collecting as a hobby

Plant collecting may also refer to a hobby, in which the hobbyist takes identifiable samples of plant species found in nature, dries them, and stores them in a paper sheet album, a simple herbarium, along with the information of the finding location, finding date, etc. necessary scientific information. As in many collecting hobbies, rarer specimens have been valued. However, when collecting living organisms, the conservation aspects must precede the collector's ambitions. This has led in some cases to a collector voluntarily taking part, helping scientists, in some research areas, provided he can store the "collectible". In fact, historically, many species have initially been found within a collection of a collector.

Usually, a plant can be identified in nature, since they are stationary. The advent of digital cameras has led many plant collectors to switch totally to photography. Some have switched to collecting live specimens of various plant species in their gardens, building a sort of "private botanical garden". Some have specialized in a specific group, the orchids and the roses and their cultivars are among the most collected. [12]

Poaching

Illegal collection of plants is known as plant poaching. A report on the risk of rare plant poaching has provided data showing possible connections between geography and the rate of poaching in the Shenandoah National Park, Virginia, USA.[13] The openings for poaching were found to be increased in locations with easy accessibility, such as roads, trails, and developed areas. The condition of the environment can determine the levels of poaching, with regions of higher quality receiving more attention from poachers.

Ethics

The hobby and practice of plant collecting is known to have been the cause of declines in certain plant populations.[14] This can be the result of hobbyists being oblivious to the status of a particular species, collectors of valuable species for profit, or researchers over collecting to fill slots in herbaria. This issue can be solved with proper research on the status of species before a plant is collected and taking the smallest sample possible.

Safety and precautions

While plant collecting may seem like a very safe and harmless practice, there is a few things collectors should keep in mind to protect themselves. First collectors should always be aware of the land where they are collecting. As in hiking there will be certain limitations to whether or not public access is granted on a plot of land and if collection from that land is allowed. For example, in a National park of the United States , plant collection is not allowed unless given special permission. Collecting internationally will involve some logistics, such as official permits which will most likely be required to bring plants both from the country of collection and to the destination country. The major herbaria can be useful to the average hobbyist in aiding them in acquiring these permits.[12]

If traveling to a remote location to access samples, it is safe practice to inform someone of your whereabouts and planned time of return. If traveling in hot weather, collectors should bring adequate water to avoid dehydration. Forms of sun protection such as sunscreen and wide brimmed hats may be essential depending on location. Travel to remote locations will most likely involve walking measurable distances in wild terrain, so precautions synonymous with those related to hiking should be taken.[12][15]

Terminology

Plant "discovery" means the first time that a new plant was recorded for science, often in the form of dried and pressed plants (a herbarium specimen) being sent to a botanical establishment such as Kew Gardens in London, where it would be examined, classified and named.[16]

Plant "introduction" means the first time that living matter – seed, cuttings or a whole plant – was brought back to Europe. Thus, the Handkerchief tree (Davidia involucrata) was discovered by Père David in 1869 but introduced to Britain by Ernest Wilson in 1901.[16]

Often, the two happened simultaneously: thus Sir Joseph Hooker discovered and introduced his Himalayan rhododendrons between 1849 and 1851.[16]

See also

- List of Irish plant collectors

- Collecting plant genetic diversity guidelines

External links

References

- ↑ Whittle, T (1970). The Plant Hunters. London: Heinemann. pp. 16.

- ↑ "A history of British gardening". BBC. Archived from the original on 2008-04-24. https://web.archive.org/web/20080424013320/http://www.bbc.co.uk/gardening/design/nonflash_victorian3.shtml. Retrieved 2008-03-07.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Collecting Plants". http://www.amnh.org/explore/curriculum-collections/biodiversity-counts/plant-identification/collecting-plants.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Preparing And Storing Herbarium Specimens". https://www.nps.gov/museum/publications/conserveogram/11-12.pdf.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "How to Collect, Press and Mount Plants". http://store.msuextension.org/publications/AgandNaturalResources/MT198359AG.pdf.

- ↑ "How to Press and Preserve Plants". http://www.amnh.org/explore/curriculum-collections/biodiversity-counts/plant-identification/how-to-press-and-preserve-plants/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Making a Plant Collection". http://www.sdnhm.org/science/botany/resources/general-information/how-to-make-a-plant-collection/.

- ↑ "BRIT Herbarium". http://www.brit.org/herbarium/plantcollecting/storage.

- ↑ Bean, A.R., ed (2006). Collecting and preserving plant specimens, A Manual. Queensland Herbarium, Environmental Protection Agency Biodiversity Sciences unit, Brisbane. ISBN 1-920928-06-5. http://www.qld.gov.au/environment/assets/documents/plants-animals/herbarium/collecting-manual.pdf.

- ↑ "Plant DNA Barcode Project" (in en). http://botany.si.edu/projects/dnabarcode/index.htm.

- ↑ Culley, Theresa M. (29 October 2013). "Why vouchers matter in botanical research1". Applications in Plant Sciences 1 (11). doi:10.3732/apps.1300076. PMID 25202501.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 http://www.brit.org/sites/default/files/public/Herbarium/Plant_Collection_and_Preservation_01.pdf

- ↑ Young, John A.; Manen, Frank T. van; Thatcher, Cindy A. (2011-09-01). "Geographic Profiling to Assess the Risk of Rare Plant Poaching in Natural Areas" (in en). Environmental Management 48 (3): 577–587. doi:10.1007/s00267-011-9687-3. ISSN 0364-152X. Bibcode: 2011EnMan..48..577Y. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00267-011-9687-3.

- ↑ Norton, David A.; Lord, Janice M.; Given, David R.; Lange, Peter J. De (1994-01-01). "Over-Collecting: An Overlooked Factor in the Decline of Plant Taxa". Taxon 43 (2): 181–185. doi:10.2307/1222876.

- ↑ "Collecting and preserving plant specimens, a manual". https://www.qld.gov.au/environment/assets/documents/plants-animals/herbarium/collecting-manual.pdf.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Toby Musgrave; Chris Gardner; Will Musgrave (1999). The Plant Hunters. Seven Dials. pp. 10–11. ISBN 1-84188-001-9.