Philosophy:Tao yin

| Tao yin |

|---|

Tao yin, also called Taoist Neigong, is a series of body and mind unity exercises (Divided into Yin, lying and sitting positions, and more Yang, standing and moving positions) practiced by Taoists to cultivate Jing (essence) and direct and refine qi, the internal energy of the body according to Traditional Chinese medicine.[1] The practice of Tao Yin was a precursor of qigong,[2] and was practised in Chinese Taoist monasteries for health and spiritual cultivation.[2] Tao Yin is also said to be[3] a primary formative ingredient in the well-known "soft style" Chinese martial art, T'ai Chi Ch'uan.[4]

The main goal of Tao yin is to create balance between internal and external energies and to revitalize the body, mind and spirit, developing strength and flexibility in muscles and tendons.

The Daoyintu

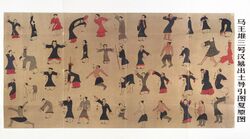

A painted scroll on display at the Hunan Provincial Museum and known as the Daoyintu found in tomb three at Mawangdui in 1973 and dated to 168 BC shows coloured drawings of 44 figures in standing and sitting postures doing Tao yin exercises. It is the earliest physical exercise chart in the world so far and illustrates a medical system which does not rely on external factors such as medication, surgery or treatments but internal factors to prevent disease.

The images include men and women, young and old. Their postures and movements differ from one another. Some are sitting, some are standing, and still others are practising Daoyintu or exercising using apparatuses.

Translation of the texts covering the document show that the early Chinese were aware of the need for both preventative and treatment based breathing exercises. The exercises can be divided into three categories:

- Postures of bodily exercises such as stretching arms and legs, leaning over, hopping, dancing, breathing exercises and using various equipment such as a stick and a ball.

- Imitating animal behaviour such as dragon, monkey, bear and crane.

- Exercises targeted at specific diseases.[5]

Effects

A typical Tao Yin exercise will involve movement of the arms and body in time with controlled inhalation and exhalation. Each exercise is designed with a different goal in mind, for example calmative effects or expanded lung capacity.

Some of the exercises act as a means of sedating, some as a stimulant or a tonification , whilst others help in the activation, harnessing and cultivation of internal Ch'i energy and the external Li life force. Through the excellent health that is gained thereby, they all assist in the opening up of the whole body, enhance the functioning of the autonomic nervous system, increase the mental capacity of the brain, give greater mind control, increase perception and intuition, uplift moral standards, and give tranquillity to the mind, which in turn confers inner harmony and greater happiness. As time goes by, these exercises slowly open up the functional and control channels that feed and activate the energy, nervous and psychic centres, enabling the individual to have a deeper understanding, consciousness and awareness of the spiritual world.[6]

According to Mantak Chia (Taoist Master and creator of the Universal Healing Tao System) the practice of Tao Yin has the following effects: harmonization of the chi, relaxation of the abdominal muscles and the diaphragm, training of the "second brain" in the lower abdomen, improvement of health and structural alignment.[7]

See also

- Chinese alchemy

- Dantian

- Internal alchemy

- Lee-style t'ai chi ch'uan

- Silk reeling

- Taoist sexual practices

- Wudangshan

- Yin Yoga

- Zhang Sanfeng

- Aiki

- Jing

References

- ↑ Taoist Ways of Healing by Chee Soo chapter 11 Tao Yin - Taoist Respiration Therapy page 113(Aquarian Press/Thorsons - HarperCollins 1986

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Huang, Jane (1987). The Primordial Breath, Vol. 1. Original Books, Inc. ISBN 0-944558-00-3.

- ↑ Eberhard, Wolfram (1986). A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols: Hidden Symbols in Chinese Life and Thought. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London. ISBN 0-415-00228-1. https://archive.org/details/dictionaryofchin00wolf.

- ↑ Lao, Cen (April 1997). The Evolution of T'ai Chi Ch'uan – T'AI CHI The International Magazine of T'ai Chi Ch'uan Vol. 21 No. 2. Wayfarer Publications. ISSN 0730-1049.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-07-16. https://web.archive.org/web/20160716012412/http://www.hnmuseum.com/hnmuseum/eng/collection/collectionContent.jsp?infoid=013224276c214028848331f4e86b0aef. Retrieved 2017-03-12.

- ↑ Taoist Ways of Healing by Chee Soo chapter 11 Tao Yin - Taoist Respiration Therapy page 114(Aquarian Press/Thorsons - HarperCollins 1986

- ↑ Chia, Mantak (September 2005). Energy Balance through the Tao: Exercises for Cultivating Yin Energy.. Destiny Books.. ISBN 159477059X.

External links

- Entry on Daoyin from the Center for Daoist Studies

- The origin of Daoyin Inscription from a Warring State Period cultural relic - neigong.net

- Theory of essence Qi and spirit - neigong.net

- Entry on Tao Yin at the Seahorse Mediawiki

- 马王堆汉墓陈列全景数字展厅—湖湖南省博物馆 (Virtual tour of the Mawangdui Han Tombs exhibit at the Hunan Provincial Museum).