Engineering:Scavenging (engine)

Scavenging is the process of replacing the exhaust gas in a cylinder of an internal combustion engine with the fresh air/fuel mixture (or fresh air, in the case of direct-injection engines) for the next cycle. If scavenging is incomplete, the remaining exhaust gases can cause improper combustion for the next cycle, leading to reduced power output.

Scavenging is equally important for both two-stroke and four-stroke engines. Most modern four-stroke engines use crossflow cylinder heads and valve timing overlap to scavenge the cylinders. Modern two-stroke engines use either Schnuerle scavenging (also known as "loop scavenging") or uniflow scavenging.

The scavenge or scavenging port refers to that port through which clean air enters the cylinder, the exhaust port through which it leaves.

Origins

The first engines deliberately designed to encourage scavenging were gas engines built by Crossley Brothers Ltd in the United Kingdom in the early 1890s. These Crossley Otto Scavenging Engines were made possible by the recent change from slide valves to poppet valves, which allowed more flexible control over valve timing events.[1] The closing of the exhaust valve occurred more than 30 degrees later than on earlier engines, giving a long 'overlap' period (when both the intake and exhaust valves are open). As these were gas engines they did not require a long period of valve closure during the compression stroke. The exhaust gases were drawn from the engine by a partial vacuum following in the wake of a 'slug' of exhaust gas from the previous combustion cycle.

This method requires that the exhaust pipe is long enough to contain the gas slug for the entire duration of the stroke. As the Crossley engine was so slow-revving, this resulted in an exhaust pipe with a length of 65 feet (20 m) between the engine and its cast-iron 'pot' silencer.[2]

Types of scavenging

Crossflow Scavenging

thumb|upright|Cross flow scavenging with a deflector piston

Crossflow cylinder heads are used by most modern 2-stroke engines, whereby the intake ports are located on one side of the combustion chamber and the exhaust ports are on the other side. The momentum of the gases assists in scavenging during the 'overlap' phase (when the intake and exhaust valves are simultaneously open).

Vertical loop Scavenging

For two-stroke engines, crossflow scavenging was used in early crankcase-compression engines, such as used by small motorcycles. The transfer port (where the fuel/air mixture enters the combustion chamber) and the exhaust port were located on opposite sides of the combustion chamber. This arrangement had the advantage of simplicity, but it also directed the incoming charge directly towards the exhaust port. To improve the emptying of the cylinder of exhaust gases and retain more of the incoming charge in the cylinder, a deflector piston was often used. This piston shape directed the intake gases towards the top of the cylinder to push the exhaust fumes down and out the exhaust port. However, the deflector piston was not very effective in practice - much of the gas flow took a shortcut path and still failed to reach the top of the cylinder - and the shape of the piston compromised the shape of the combustion chamber by causing long flame paths and excessive surface area. Therefore, vertical loop scavenging is rarely used in modern two-stroke engines.

Schnuerle Scavenging

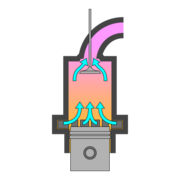

Schnuerle scavenging (sometimes called "loop scavenging" or "reverse scavenging") is a design used by most modern valveless two-stroke engines. The key difference compared to crossflow scavenging is that the transfer ports are located either side of the exhaust port and aimed at the opposite cylinder wall.[3] As the fuel/air mixture enters the combustion chamber, it travels across the cylinder then up the cylinder wall opposite the exhaust port before looping over at the cylinder head and back down to the exhaust port. This long flow path and opposite directions of intake and exhaust flows minimizes the mixing of the fresh and spent gases and limits the amount of fresh charge which escapes the cylinder prior to the ports closing. This scavenging method does require a greater understanding of the 3-dimensional gas flow in the cylinder and more care in the placement, size, and angle of the various ports.

Uniflow scavenging

Uniflow scavenging is a design in which the fresh intake charge and exhaust gases flow in the same direction. This requires that the intake and exhaust ports be at opposite ends of the cylinder. As used by some two-stroke engines, the fresh charge enters through piston-controlled ports near the bottom of the cylinder and flows upward, pushing the exhaust gases out through poppet valves located in the cylinder head. Other uniflow engines - such as the Ricardo Dolphin marine engine - use a downward flow direction, with the fresh air/fuel mixture entering at the top of the cylinder and the exhaust gases exiting at towards the bottom of the cylinder. Yet another design uses piston-controlled ports at both ends of the cylinder and two opposed pistons in each cylinder moving in opposite directions to compress the charge between them.

The uniflow method of scavenging has been often used for two-stroke diesel engines in motor vehicles, marine vessels, railway locomotives and as stationary engines. Its drawback is the additional complexity, mass, volume, and cost required to implement the poppet valvetrain (or the additional crankshaft or rocker arms required to control a second piston).

See also

References

- ↑ Clerk, Dugald (1907). The Gas and Oil Engine. pp. 312–313. https://www.forgottenbooks.com/en/readbook/TheGasandOilEngine_10014378#325.

- ↑ Smith, Philip H. (1962). The Scientific Design of Exhaust and Intake Systems (1st ed.). GT Foulis. pp. 29–30.

- ↑ "Loop Scavenging and Boost Ports". http://twostrokehistoryplus.jigsy.com/loop-scavenging-and-boost-ports. Retrieved 5 October 2019.

|