Functional Database Model

The functional database model is used to support analytics applications such as financial planning and performance management. The functional database model, or the functional model for short, is different from but complementary to the relational model. The functional model is also distinct from other similarly named concepts, including the DAPLEX functional database model[1] and functional language databases. The functional model is part of the online analytical processing (OLAP) category since it comprises multidimensional hierarchical consolidation. But it goes beyond OLAP by requiring a spreadsheet-like cell orientation, where cells can be input or calculated as functions of other cells. Also as in spreadsheets, it supports interactive calculations where the values of all dependent cells are automatically up to date whenever the value of a cell is changed.

Overview

Analytics, especially forward looking or prospective analytics requires interactive modeling, "what if", and experimentation of the kind that most business analysts do with spreadsheets. This interaction with the data is enabled by the spreadsheet’s cell orientation and its ability to let users define cells calculated as a function of other cells.

The relational database model has no such concepts and is thus very limited in the business performance modeling and interactivity it can support. Accordingly, relational-based analytics is almost exclusively restricted to historical data, which is static. This misses most of the strategic benefits of analytics, which come from interactively constructing views of the future.

The functional model is based on multidimensional arrays, or "cubes", of cells that, as in a spreadsheet, can be either externally input, or calculated in terms of other cells. Such cubes are constructed using dimensions which correspond to hierarchically organized sets of real entities such as products, geographies, time, etc. A cube can be seen as a function over the cartesian product of the dimensions. I.e., it assigns a value to each cell, which is identified by an n-tuple of dimension elements; thus the name "functional". The model retains the flexibility and potential for interactivity of spreadsheets, as well as the multidimensional hierarchical consolidations of relational-based OLAP tools. At the same time, the functional model overcomes the limitations of both the relational database model and classical spreadsheets.

Products that implement the principles of the functional model to varying degrees have been in existence for some time, including products such as Essbase, TM1, Alea, Microsoft Analysis Services, etc.[2][3][4]

Analytics context

The management system of an enterprise generally consists of a series of interconnected control loops. Each loop starts by developing a plan, the plan is then executed, and the results are reviewed and compared against the plan. Based on those results, and a new assessment of what the future holds, a new plan is developed and the process is repeated. The three components of the control loop, planning, execution and assessment, have different time perspectives. Planning looks at the future, execution looks at the present and review looks at the past.

Information Technology (IT) plays now a central role in making management control loops more efficient and effective. Operational computer systems are concerned with execution while analytic computer systems, or simply Analytics, are used to improve planning and assessment. The information needs of each component are different. Operational systems are typically concerned with recording transactions and keeping track of the current state of the business – inventory, work in progress etc. Analytics has two principal components: forward-looking or prospective analytics, which applies to planning, and backward looking or retrospective analytics, which applies to assessment.

In retrospective analytics, transactions resulting from operations are boiled down and accumulated into arrays of cells. These cells are identified by as many dimensions as are relevant to the business: time, product, customer, account, region, etc. The cells are typically arrayed in cubes that form the basis for retrospective analyses such as comparing actual performance to plan. This is the main realm of OLAP systems. Prospective analytics develops similar cubes of data but for future time periods. The development of prospective data is typically the result of human input or mathematical models that are driven and controlled through user interaction.

The application of IT to the tree components of the management control loop evolved over time as new technologies were developed. Recording of operational transactions was one of the first needs to be automated through the use of 80 column punch cards. As electronics progressed, the records were moved, first to magnetic tape, then to disk. Software technology progressed as well and gave rise to database management systems that centralized the access and control of the data.

Databases made it then possible to develop languages that made it easy to produce reports for retrospective analytics. At about the same time, languages and systems were developed to handle multidimensional data and to automate mathematical techniques for forecasting and optimization as part of prospective analytics. Unfortunately, this technology required a high level of expertise and was not comprehensible to most end users. Thus its user acceptance was limited, and so were the benefits derived from it.

No wide-use tool was available for prospective analytics until the introduction of the electronic spreadsheet. For the first time end users had a tool that they could understand and control, and use it to model their business as they understood it. They could interact, experiment, adapt to changing situations, and derive insights and value very quickly. As a result, spreadsheets were adopted broadly and ultimately became pervasive. To this day, spreadsheets remain an indispensable tool for anyone doing planning.

Spreadsheets and the functional model

Spreadsheets have a key set of characteristics that facilitate modeling and analysis. Data from multiple sources can be brought together in one worksheet. Cells can be defined by means of calculation formulas in terms of other cells, so facts from different sources can be logically interlinked to calculate derived values. Calculated cells are updated automatically whenever any of the input cells on which they depend changes. When users have a "what if" question, they simply change some data cells, and automatically all dependent cells are brought up to date. Also, cells are organized in rectangular grids and juxtaposed so that significant differences can be spotted at a glance or through associated graphic displays. Spreadsheet grids normally also contain consolidation calculations along rows and or columns. This permits discovering trends in the aggregate that may not be evident at a detailed level.

But spreadsheets suffer from a number of shortcomings. Cells are identified by row and column position, not the business concepts they represent. Spreadsheets are two dimensional, and multiple pages provide the semblance of three dimensions, but business data often has more dimensions. If users want to perform another analysis on the same set of data, the data needs to be duplicated. Spreadsheet links can sometimes be used, but most often are not practical. The combined effect of these limitations is that there is a limit on the complexity of spreadsheets that can be built and managed. While the functional model retains the key features of the spreadsheet, it also overcomes its main limitations. With the functional model, data is arranged in a grid of cells, but cells are identified by business concept instead of just row or column. Rather than worksheets, the objects of the functional model are dimensions and cubes. Rather than two or three dimensions: row, column and sheet, the functional model supports as many dimensions as are necessary.

Another advantage of the functional model is that it is a database with features such as data independence, concurrent multiuser access, integrity, scalability, security, audit trail, backup/recovery, and data integration. Data independence is of particularly high value for analytics. Data need no longer reside in spreadsheets. Instead the functional database acts as a central information resource. The spreadsheet acts as a user interface to the database, so the same data can be shared by multiple spreadsheets and multiple users. Updates submitted by multiple users are available to all users subject to security rules. Accordingly, there is always a single consistent shared version of the data.

Components of the functional model

A functional database consists of a set of dimensions which are used to construct a set of cubes. A dimension is a finite set of elements, or members, that identify business data, e.g., time periods, products, areas or regions, line items, etc. Cubes are built using any number of dimensions. A cube is a collection of cells, each of which is identified by a tuple of elements, one from each dimension of the cube. Each cell in a cube contains a value. A cube is effectively a function that assigns a value to each n-tuple of the cartesian product of the dimensions.

The value of a cell may be assigned externally (input), or the result of a calculation that uses other cells in the same cube or other cubes. The definition of a cube includes the formulas that specify the calculation of such cells. Cells may also be empty and deemed to have a zero value for purposes of consolidation.

As with spreadsheets, users need not worry about executing recalculation. When the value of a cell is requested, the value that is returned is up to date with respect to the values of all of the cells that go into its calculation i.e. the cells on which it depends.

Dimensions typically contain consolidation hierarchies where some elements are defined as parents of other elements, and a parent is interpreted as the sum of its children. Cells that are identified by a consolidated element in one or more dimensions are automatically calculated by the functional model as sums of cells having child elements in those dimensions. When the value of a consolidated cell is requested, the value that is returned is always up to date with respect to the values of all of the cells that it consolidates.

An example

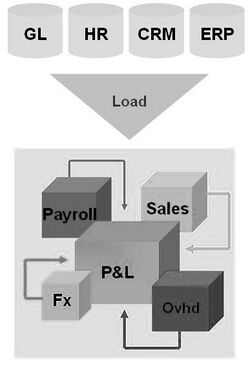

The cubes and their dimensions (in parentheses) are as follows:

- Profit and Loss - P&L (Region, Account, Currency, Time)

- Sales - Sales(Region, Product, Time)

- Payroll - Payroll(Region, Employee, Time)

- Overhead - Ovhd(Account, Time)

- Foreign Exchange - Fx(Currency, Time)

The cubes in the model are interconnected through formulas:

The P&L cube picks up the dollar costs from the payroll cube through a formula of the form: P&L( "Payroll", "Dollars") = Payroll ("All Employees")

Note: The expression syntax used is for illustration purposes and may not reflect syntax used in the formal model or in particular products that implement the functional model. The dimensions that are omitted from the expression are assumed to range over all the leaf elements of those dimensions. Thus this expression is equivalent to:

P&L( xRegion, "Payroll", "Dollars", xTime) = Payroll (xRegion, "All Employees", xTime), for all leaves xRegion in Region and all leaves xTime in Time.

Similarly, P&L also picks up sales revenue from the Sales cube through:

P&L( "Sales", "Dollars") = Sales("All Products")

Overhead accounts are allocated by region on the basis of sales:

P&L("Region", "Dollars") = Ovhd() * Sales("Region") / Sales("All Regions")

Finally, other currencies are derived from the dollar exchange rate:

P&L() = P&L("Dollars") * Fx()

The historical portion of the cubes is also populated from the data warehouse. In this simplified example, the calculations just discussed may be done in the data warehouse for the historical portion of the cubes, but generally, the functional model supports the calculation of other functions, such as ratios and percentages.

While the history is static, the future portion is typically dynamic and developed interactively by business analysts in various organizations and various backgrounds. Sales forecasts should be developed by experts from each region. They could use forecasting models and parameters that incorporate their knowledge and experience of that region, or they could simply enter them through a spreadsheet. Each region can use a different method with different assumptions. The payroll forecast could be developed by HR experts in each region. The overhead cube would be populated by people in headquarters finance, and so would the exchange rate forecasts. The forecasts developed by regional experts are first reviewed and recycled within the region and then reviewed and recycled with headquarters.

The model can be expanded to include a Version dimension that varies based on, for example, various economic climate scenarios. As time progresses, each planning cycle can be stored in a different version, and those versions compared to actual and to one another.

At any time the data in all the cubes, subject to security constraints, is available to all interested parties. Users can bring slices of cubes dynamically into spreadsheets to do further analyses, but with a guarantee that the data is the same as what other users are seeing.

Functional databases and prospective analytics

A functional database brings together data from multiple disparate sources and ties the disparate data sets into coherent consumable models. It also brings data scattered over multiple spreadsheets under control. This lets users see a summary picture that combines multiple components, e.g., to roll manpower planning into a complete financial picture automatically. It gives them a single point of entry to develop global insights based on various sources.

A functional database, like spreadsheets, also lets users change input values while all dependent values are up to date. This facilitates what-if experimentation and creating and comparing multiple scenarios. Users can then see the scenarios side by side and choose the most appropriate. When planning, users can converge on a most advantageous course of action by repeatedly recycling and interacting with results. Actionable insights come from this intimate interaction with data that users normally do with spreadsheets

A functional database does not only provide a common interactive data store. It also brings together models developed by analysts with knowledge of a particular area of the business that can be shared by all users. To facilitate this, a functional database retains the spreadsheet’s interactive cell-based modelling capability. This makes possible models that more closely reflect the complexities of business reality.

Perhaps a functional database’s largest single contribution to analytics comes from promoting collaboration. It lets multiple individuals and organizations not only share a single version of the truth, but a truth that is dynamic and constantly changing. Its automatic calculations quickly consolidate and reconcile inputs from multiple sources. This promotes interaction of various departments, facilitates multiple iterations of thought processes and makes it possible for differing viewpoints to converge and be reconciled. Also, since each portion of the model is developed by the people that are more experts in their particular area, it is able to leverage experience and insights that exist up and down the organization.

References

- ↑ Shipman D.W. The functional data model and the data language DAPLEX. ACM Transactions on Database Systems 6(1), March 1981, p. 140-173.

- ↑ George Spofford, Sivakumar Harinath, Chris Webb, Dylan Hai Huang, Francesco Civardi: MDX-Solutions: With Microsoft SQL Server Analysis Services 2005 and Hyperion Essbase. Wiley, 2006, ISBN:0-471-74808-0

- ↑ Jedox OLAP http://www.jedox.com/en/products/jedox-olap.html

- ↑ Infor PM OLAP Server http://www.infor.com/content/brochures/infor-pm-olap.pdf/

Further reading

- "Basic Set Theory". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/set-theory/primer.html

- Bird R.S., Wadler P.L. Introduction to Functional Programming. Prentice Hall (1988).

- Buneman P., Functional Database Languages and the Functional Data Model. A position paper for the FDM workshop (June 1997) http://www.cis.upenn.edu/~peter/fdm-position.html.

- Codd, E. F. A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks. Comm. ACM 13, 6 (June, 1970)

- Henderson P. Functional Programming Application and Implementation. Prentice Hall (1980).

- Hrbacek, K and Jech, T Introduction to Set Theory, Third Edition, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York 1999.

- Lang, Serge (1987), Linear algebra, Berlin, New York: Springer-Verlag, ISBN:978-0-387-96412-6

- C.M. Necco, J.N. Oliveira, L. Quintas. A functional approach for on line analytical processing, 2006. WISBD, III Workshop de I ngeniería de Software y Bases de Datos. CACIC'06, XII Congreso Argentino de Ciencias de la Computación, Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Argentina.

- E. F. Codd. Providing olap to user-analysts: an it mandate, Apr. 1993. Technical Report, E. F. Codd and Associates.

- P. Trinder, A functional data base, D.Phil Thesis, Oxford University 1989.

- G. Colliat, Olap relational and multidimensional database systems, SIGMOD Record, 25(3), (1996)

- T. B. Pedersen, C. S. Jensen, Multidimensional database technology, IEEE Computer 34(12), 40-46, (2001)

- C. J. Date with Hugh Darwen: A Guide to the SQL standard : a users guide to the standard database language SQL, 4th ed., Addison Wesley, USA 1997, ISBN:978-0-201-96426-4

- Ralph Kimball and Margy Ross, The Data Warehouse Toolkit: The Complete Guide to Dimensional Modeling (Second Edition), p. 393

- Karsten Oehler Jochen Gruenes Christopher Ilacqua, IBM Cognos TM1 The Official Guide, McGraw Hill 2012