Philosophy:The Family of Man

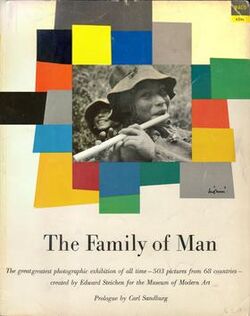

The Family of Man was an ambitious[1] photography exhibition curated by Edward Steichen, the director of the Museum of Modern Art's (MoMA) Department of Photography. It was first shown in 1955 from January 24 to May 8 at the New York MoMA, then toured the world for eight years to record-breaking audience numbers.

According to Steichen, the exhibition represented the "culmination of his career."[2]

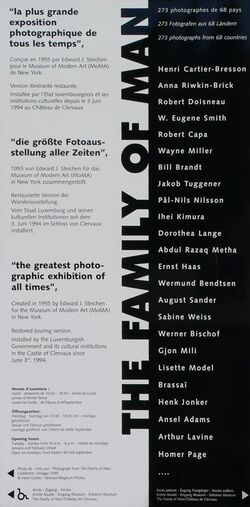

The physical collection is archived and displayed[3] at Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg (Edward Steichen's home country; he was born there in 1879 in Bivange). It was first presented there in 1994 after restoration of the prints.[4]

In 2003 the Family of Man photographic collection was added to UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in recognition of its historical value.[5]

World tour

Part of the Museum of Modern Art's International Program the exhibition The Family of Man toured the world, making stops in thirty-seven countries on six continents. More than 9 million people viewed the exhibit, which is still in excess of the audience for any photographic exhibition since.The photographs included in the exhibition, which is still on display, focus on the commonalities that bind people and cultures around the world and the exhibition itself served as an expression of humanism in the decade following World War II.[6]

The recently-formed United States Information Agency was instrumental in touring the photographs throughout the world in five different versions for seven years, under the auspices of the Museum of Modern Art International Program.[7] Notably, it was not shown in Franco's Spain, in Vietnam, nor in China. Copy 5: Following a bilateral agreement between the USA and USSR, in 1959 the American National Exhibition was to be held in Moscow and the Russians were to have the use of New York City's Coliseum. This Moscow trade fair at Sokolniki Park was the scene of Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and United States Vice President Richard Nixon's 'Kitchen Debate' over the relative merits of communism and capitalism. The Family of Man was a late inclusion not originally envisaged in MoMA's itinerary. With a grant to the Museum of $15,000 (less than half of what it requested) and funding from the plastics industry for the radical pre-fabricated translucent pavilion design to house it, a fifth copy of the show was salvaged from what was left from Beruit and Scandinavia showings, augmented with new prints.[8] In Moscow, in the context of a trade show 'supermarket' meant to demonstrate lavish consumerism, and a multimedia display assembled by Charles Eames, the collection's overtones of peace and human brotherhood symbolized a lifting of the overhanging danger of an atomic war for Soviet citizens in the midst of the Cold War.[9] This meaning seemed to be grasped especially by Russian students and intellectuals.[9] Recognising the importance of the Moscow exhibition as "the high spot of the project"[10] Steichen attended its opening and made copious photographs of the event.[8]

The original prints from Copy 3 exhibited in the permanent collection at Clervaux Castle in Luxembourg have been restored twice, once in the 1990s and more comprehensively during a closure of the museum in the years 2010-2013.[2]

An innovative exhibit

The physical installation and layout of the Family of Man exhibition aimed to enable the visitor to read this as a photo-essay[11] about human development and cycles of life affirming a common human identity and destiny against the contemporary Cold War threats of nuclear war.

Architect Paul Rudolph designed a series of temporary walls among the existing structural columns[12] guiding visitors past the images,[13] the effect of which he described as "telling a story",[14] encouraging them to pause at those which attracted their attention. HIs layout was accommodated as closely as possible, using his display features, in the international venues which varied considerably from the original space at MoMA.

Open spaces within the layout required viewers to make their own decisions about their passage through the exhibition, and to gather to discuss it. The layout and placement of prints and their variation in size encouraged the bodily participation of the audience, who would have to bend to examine a small print displayed below eye level and then to step back to view a mural image, and to negotiate both narrow and expansive spaces.[15]

The prints range in size from 24 x 36 cm to 300 x 400 cm and were made by his assistant Jack Jackson,[16] in the case of the contemporary images, from the negative supplied to Steichen by each photographer. Also included were copies of historical images including a Matthew Brady civil war documentation and a Lewis Carroll portrait.[8] Blown-up, often mural scale images, angled, floated or curved, some inset into other floor-to-ceiling prints, even displayed on the ceiling (a canted view of a silhouetted axeman and tree), on posts like finger-boards (in the final room), and the floor (for a Ring o' Roses series), were grouped together according to diverse themes. Repeated prints of Eugene Harris' portrait of a Peruvian flute-player forming a coda, or acting as 'Pied Piper' to the audience in the opinion of some reviewers,[15][17] and according to Steichen himself, expressing "a little bit of mischief, but much sweetness—that's the song of life."[18] Lighting intensities varied throughout the series of ten rooms in order to set the mood.

The exhibition opened with an entrance archway papered with a blow-up of a crowd in London by Pat English framing Wyn Bullock's Chinese landscape of sunlight on water into which was inset an image of a truncated nude of a pregnant woman in an evocation of creation myths. Subjects then ranged in sequence from lovers, to childbirth, to household, and careers, then to death and on a topical portentous note, the hydrogen bomb (an image from LIFE magazine of the test detonation Mike, Operation Ivy, Enewetak Atoll, October 31, 1952) which was the only full-colour image; a room-filling backlit 1.8m x 2.43m Eastman transparency, replaced for the travelling version of the show with a different view of the same explosion in black and white.

Finally, full cycle, visitors returned once more to children in a room in which the last picture was W. Eugene Smith's iconic 1946 A Walk to Paradise Garden. As the centrepiece of the exhibition a hanging sculptural installation of photographs including Vito Fiorenza's Sicilian family group and Carl Mydans' of a Japanese family (both from nations which were recent enemies of the Allies in WW2), another from Bechuanaland by Nat Farbman and a rural family of the United States by Nina Leen, encouraged circulation to view double-sided prints and invited reflection on the universal nature of the family beyond cultural differences.

Photos were chosen according to their capacity to communicate a story, or a feeling, that contributed to the overarching narrative. Each grouping of images builds upon the next, creating an intricate story of human life. The design of the exhibition built on trade displays and Steichen's 1945 Power In The Pacific exhibition which was designed by George Kidder Smith for MoMA, Steichen's commissioning of Herbert Bayer for the presentation of his curatorship of other exhibitions and his own long history of initiation of innovative exhibits dating back to his association with Gallery 291 early in the century.[15][19] In 1963 Steichen elaborated on the special opportunities offered by the exhibition format;

In the cinema and television, the image is revealed at a pace set by the director. In the exhibition gallery, the visitor sets his own pace. He can go forward and then retreat or hurry along according to his own impulse and mood as these are stimulated by the exhibition. In the creation of such an exhibition, resources are brought into play that are not available elsewhere. The contrast in scale of images, the shifting of focal points, the intriguing perspective of long- and short- range visibility with the images to come being glimpsed beyond the images at hand —all these permit the spectator an active participation that no other form of visual communication can give.[20]

Texts used in the exhibition and book

The enlarged prints by the multiple photographers were displayed without explanatory captions, and instead were intermingled with quotations by, among others, James Joyce, Thomas Paine, Lillian Smith, and William Shakespeare, chosen by photographer and social activist Dorothy Norman.[21] Carl Sandburg, Steichen's brother-in-law, 1951 recipient of the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and known for his biography of Abraham Lincoln, wrote an accompanying poetic commentary also displayed as text panels throughout the exhibition and included in the publication, of which the following are a sample;

There is only one man in the world and his name is All Men. There is only one woman in the world and her name is All Women. There is only one child in the world and the child's name is All Children.People! flung wide and far, born into toil, struggle, blood and dreams, among lovers, eaters, drinkers, workers, loafers, fighters, players, gamblers. Here are ironworkers, bridge men, musicians, sandhogs, miners, builders of huts and skyscrapers, jungle hunters, landlords, and the landless, the loved and the unloved, the lonely and abandoned, the brutal and the compassionate — one big family hugging close to the ball of Earth for its life and being. Everywhere is love and love-making, weddings and babies from generation to generation keeping the Family of Man alive and continuing.

If the human face is "the masterpiece of God" it is here then in a thousand fateful registrations. Often the faces speak that words can never say. Some tell of eternity and others only the latest tattings. Child faces of blossom smiles or mouths of hunger are followed by homely faces of majesty carved and worn by love, prayer and hope, along with others light and carefree as thistledown in a late summer wing. Faces have land and sea on them, faces honest as the morning sun flooding a clean kitchen with light, faces crooked and lost and wondering where to go this afternoon or tomorrow morning. Faces in crowds, laughing and windblown leaf faces, profiles in an instant of agony, mouths in a dumbshow mockery lacking speech, faces of music in gay song or a twist of pain, a hate ready to kill, or calm and ready-for-death faces. Some of them are worth a long look now and deep contemplation later.

A popular publication

Jerry Mason (1914–1991) contemporaneously edited and published a complimentary book[22] of the exhibition through Ridge Press,[23] formed for the purpose in 1955 in partnership with Fred Sammis.[24] The book, which has never been out of print, was designed by Leo Lionni (May 5, 1910 – October 11, 1999) and reproduced in a variety of formats (most popularly a soft-cover volume)[25] in the 1950s, and reprinted in large format for its 40th anniversary, and in its various editions has sold more than four million copies. Most images from the exhibition were reproduced with an introduction by Carl Sandburg, whose prologue reads, in part:

The first cry of a baby in Chicago, or Zamboango, in Amsterdam or Rangoon, has the same pitch and key, each saying, "I am! I have come through! I belong! I am a member of the Family. Many the babies and grownup here from photographs made in sixty-eight nations round our planet Earth. You travel and see what the camera saw. The wonder of human mind, heart wit and instinct is here. You might catch yourself saying, 'I'm not a stranger here.' [26]

However, an omission from the book, highly significant and contrary to Steichen's stated pacifist aim, was the image of a hydrogen bomb test explosion; audiences of the time were highly sensitive to the threat of universal nuclear annihilation.[27] In place of the huge colour transparency to which a space was devoted in the MoMA exhibition, and the black-and-white mural print that toured countries other than Japan, only this quotation of Bertrand Russell's anti-nuclear warning, in white type on a black page, appears in the book;[28]

[...] The best authorities are unanimous in saying that a war with hydrogen bombs is quite likely to put an end to the human race [...] There will be universal death — sudden for only a minority, but for the majority a slow torture of disease and disintegration.

Absent also from the book, and removed by week eleven of the initial MoMA exhibition, was the distressing photograph of the aftermath of a lynching, of a dead young African American man, tied to a tree with his bound arms tautly tethered with a rope that stretches out of frame.[29]

For most purchasers, this was their first encounter with a book that gave priority to the photographic image over text.[8]

In 2015, to mark the sixtieth anniversary of the inaugural exhibition, MoMA reissued the book as a hardcover edition, with the original jacket design from 1955 and duotone printing from new copies of all of the photographs.[30]

Photographers

Steichen's stated objective was to draw attention, visually, to the universality of human experience and the role of photography in its documentation. The exhibition brought together 503 photos from 68 countries, the work of 273 photographers (163 of whom were Americans)[31] which, with 70 European photographers, means that the ensemble represents a primarily Western viewpoint.[32] That forty were women photographers can in some part be attributed to Joan Miller's contribution to the selection.

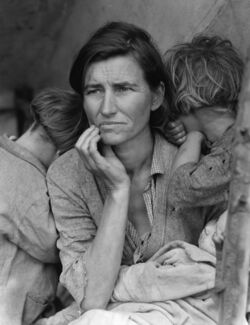

Dorothea Lange assisted her friend Edward Steichen in recruiting photographers[33] using her FSA and Life connections who in turn promoted the project to their colleagues. In 1953 she circulated a letter; "A Summons to Photographers All Over the World," calling on them to;

show Man to Man across the world. Here we hope to reveal by visual images Man's dreams and aspirations, his strength, his despair under evil. If photography can bring these things to life, this exhibition will be created in a spirit of passionate and devoted faith in Man. Nothing short of that will do.[34]

The letter then listed topics that photographs might cover and these categories are reflected in the show's final arrangement. Lange's work features in the exhibition.

Steichen and his team drew heavily on Life archives for the photographs used in the final exhibition,[35] seventy-five by Abigail Solomon-Godeau's count, more than 20% of the total (111 out of 503), while some were obtained from other magazines; Vogue was represented by nine, Fortune (7), Argosy (seven, all by Homer Page), Ladies Home Journal (4); Popular Photography (3), and others Seventeen, Glamour, Harper's Bazaar, Time (magazine) , the British Picture Post and the French Du, by one. From picture agencies American, Soviet, European and international, which also supplied the above magazines, came about 13% of the content, with Magnum represented by 43 of the pictures, Rapho with thirteen, Black Star with ten, Pix with seven, Sovfoto, which had three and Brackman with four, with around half a dozen other agencies represented by one photo.[36]

Steichen travelled internationally to collect images, through 11 European countries including France, Switzerland, Austria and Germany.[37] In total, Steichen procured 300 images from European photographers, many from the humanist group, which were first shown in the Post-War European Photography exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1953.[37] Due to the incorporation of this body of work into the 1955 The Family of Man exhibition, Post-War European Photography is thought of as a preview to The Family of Man.[37] The international tour of the definitive 1955 exhibition was sponsored by the now defunct United States Information Agency, whose aim was to counter Cold War propaganda by creating a better world image of American policies and values.[37]

Though most photographers were represented by a single picture, some had several included; Robert Doisneau, Homer Page, Helen Levitt, Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Bill Brandt, Édouard Boubat, Harry Callahan (with two), Nat Farbman (five of Bechuanaland, and more from Life), Robert Frank (four), Bert Hardy and Robert Harrington (three). Steichen himself supplied five photos, while his assistant Wayne Miller had thirteen chosen; by far the greatest number.[36]

The following lists all participating photographers (see original 1955 MoMA checklist):[38]

- Ansel Adams (USA)

- Erich Andres (Germany)

- Emmy Andriesse (Netherlands)

- Diane and Allan Arbus (U.S.A., Vogue)

- Eve Arnold (Magnum)

- Richard Avedon (U.S.A.)

- Ruth-Marion Baruch (USA)

- Hugh Bell (U.S.A.)

- Wermund Bendtsen (Denmark)

- Paul Berg (USA)

- Lou Bernstein (USA)

- John Bertolino(Italy/USA)

- Eva Besnyö (Netherlands)

- Werner Bischof

- Maria Bordy (Russia, UN)

- Édouard Boubat (France)

- Margaret Bourke-White (USA)

- Mathew Brady (USA)

- Bill Brandt (UK)

- Brassai (France)

- Manuel Álvarez Bravo (Mexico)

- Josef Breitenbach (Brackman Associates) (Germany, USA)

- David Brooks (Canada)

- Reva Brooks (Canada)

- Ernst Brunner (Switzerland)

- Esther Bubley (USA)

- Wynn Bullock (USA)

- Shirley Burden (USA)

- Rudolf Busler (Germany)

- Harry Callahan (USA)

- Cornell Capa (USA)

- Robert Capa

- Robert Carrington

- Lewis Carrol (UK)

- Henri Cartier-Bresson (France)

- Ted Castle (USA)

- Marcos Chamúdez (Chile)

- Ed Clark (USA)

- Hermann Claasen (Germany)

- Jerry Cooke (USA)

- Roy DeCarava (USA)

- Loomis Dean (USA)

- Jack Delano (USA)

- Nick De Morgoli

- J. De Pietro

- R. Diament (USSR)

- Robert Doisneau (France)

- Nell Dorr (USA)

- Nora Dumas (French)

- David Douglas Duncan (USA)

- Alfred Eisenstaedt (USA)

- Elliott Erwitt (USA)

- J.R. Eyerman (USA)

- Sam Falk (USA)

- Nat Farbman (USA)

- Eleanor Fast

- Louis Faurer (USA)

- Ed Feingersh (USA)

- Andreas Feininger (USA)

- Vito Fiorenza (Italy)

- Leopold Fischer (Austria)

- John Florea (USA)

- Robert Frank (USA)

- Toni Frissell (USA)

- Unosuke Gamou (Japan)

- William Garnett (USA)

- Herbert Gehr (USA)

- Edmund Bert Gerard

- Guy Gillette (USA)

- Burt Glinn (USA)

- Fritz Goro (USA)

- Allan Grant (USA)

- Farrell Grehan (USA)

- Rene Groebli (Switzerland)

- Mildred Grossman (USA)

- Karl W. Gullers (Sweden)

- Ernst Haas (USA)

- Peter W. Haberlin

- Hideo Haga (Japan)

- Otto Hagel (USA)

- Robert Halmi

- Hiroshi Hamaya(Japan)

- Hans Hammarskiöld (Sweden)

- Hella Hammid (USA)

- Chien Hao (China)

- Bert Hardy (UK)

- Caroline Hebbe-Hammarskiöld (Sweden)

- Willi Huttig (Germany)

- Yasohiro Ishimoto (Japan)

- Izis (France)

- Fenno Jacobs (USA)

- Raymond Jacobs (USA)

- Ronny Jacques (Canada)

- Bob Jakobsen (USA)

- Nico Jesse (Netherlands)

- Constantin Joffé

- Carter Jones

- Henk Jonker (Netherlands)

- Victor Jorgensen (USA)

- Clemens Kalisher (USA)

- Simpson Kalisher (USA)

- Consuelo Kanaga (USA)

- Dmitri Kessel (USA)

- Keystone Press (Agency, USA)

- Ihei Kimura (Japan)

- Martha Kitchen (USA)

- N. Kolli (USSR)

- Torkel Korling (USA)

- Nikolai Kozlovsky (USSR)

- Ewing Krainin

- Herman Kreider

- Walter B. Lane

- Dorothea Lange (USA)

- Harry Lapow (USA

- Lisa Larsen (USA)

- Alma Lavenson (USA)

- Arthur Lavine (USA)

- Russell Lee (USA)

- Nina Leen (Russia/USA)

- Laurence Le Guay (Australia)

- Henri Leighton

- Arthur Leipzig (USA)

- Charles Leirens

- Gita Lenz (USA)

- Leon Levinstein (USA)

- Helen Levitt (USA)

- Margery Lewis (USA)

- Sol Libsohn (USA)

- David Linton

- Herbert List (Germany)

- Jacob Lofman

- G.H. Metcalf

- Gjon Mili (Albania/USA)

- Frank Miller (USA)

- Joan Miller (USA)

- Lee Miller (USA)

- Wayne Miller (USA)

- May Mirin (USA)

- Lisette Model (Austria/USA)

- Peter Moeschlin (Switzerland)

- David Moore (Australia)

- Barbara Morgan (USA)

- Hedda Morrison (Germany)

- Ralph Morse (USA)

- Robert Mottar

- Carl Mydans (USA)

- Dave Myers

- Fritz Neugass

- Lennart Nilsson (Sweden)

- Pål Nils Nilsson (Sweden)

- Emil Obrovsky (Austria)

- Yoichi Okamoto (USA)

- Cas Oorthuys (Netherlands)

- Ruth Orkin (USA)

- Don Ornitz

- Eiju Otaki

- Homer Page (USA)

- Marion Palfi (USA)

- Gordon Parks (USA)

- Rondal Partridge (USA)

- Irving Penn (USA)

- Carl Perutz (USA)

- John Phillips (Algeria/USA)

- Leonti Planskoy

- Ray Platnick

- Fred Plaut (Germany)

- Rudolf Pollak

- Rapho Guilumette (Agency, France)

- Gottfried Rainer

- Daniel J. Ransohoff

- Bill Rauhauser (USA)

- Satyajit Ray (India)

- Anna Riwkin-Brick (Russia/Sweden)

- George Rodger (Great Britain)

- Willy Ronis (France)

- Annelise Rosenberg

- Hannes Rosenberg

- Sanford H. Roth

- Éric Schwab (France)

- Bob Schwalberg

- Kurt Severin

- David Seymour (Poland)

- Ben Shahn (Lithuania/USA)

- Musya S. Sheeler

- Li Shu

- George Silk (New Zealand/USA)

- Bradley Smith

- Ian Smith

- W. Eugene Smith (USA)

- Howard Sochurek (USA)

- Peter Stackpole (USA)

- Alfred Statler

- Gitel Steed (USA)

- Edward Steichen (Luxembourg/USA)

- Richard Steinheimer (USA)

- Ezra Stoller (USA)

- Lou Stoumen (USA)

- George Strock (USA)

- Constance Stuart (South Africa)

- Étienne Sved (Hungary)

- Suzanne Szasz

- Yoshisuke Terao

- Gustavo Thorlichen (Argentina)

- Charles Trieschmann

- François Tuefferd (France)

- Jakob Tuggener (Switzerland)

- Allan Turoff

- Doris Ulmann (USA)

- Alexander Uzylan (U.S.S.R.)

- Ed van der Elsken (Netherlands)

- William Vandivert

- Pierre Verger (France/Brazil)

- Ike Vern

- 'Véro' (Werner Rosenberg) (France)

- Roman Vishniac (Russia/USA)

- Carmel Vitullo

- Edward Wallowitch

- Sabine Weiss (Switzerland)

- Arthur Witman

- Jasper Wood

- Yosuke Yamahata (Japan)

- Shizuo Yamamato

Reception and criticism

Photography, said Steichen, "communicates equally to everybody throughout the world. It is the only universal language we have, the only one requiring no translation."[39] When the exhibition opened most reviewers loved the show, embracing the idea of this 'universal language', and lauding Steichen as a sort of author and the exhibition as a text or essay. Photographer Barbara Morgan, in Aperture, connected this concept with the show's universalising theme;

In comprehending the show the individual himself is also enlarged, for these photographs are not photographs only — they are also phantom images of our co-citizens; this woman into whose photographic eyes I now look is perhaps today weeding her family rice paddy, or boiling a fish in coconut milk. Can you look at the polygamist family group and imagine the different norms that make them live happily in their society which is so unlike — yet like — our own? Empathy with these hundreds of human beings truly expands our sense of values.[40]

Roland Barthes however was quick to criticise the exhibition as being an example of his concept of myth - the dramatization of an ideological message. In his book Mythologies, published in France a year after the exhibition in Paris in 1956, Barthes declared it to be a product of "conventional humanism," a collection of photographs in which everyone lives and "dies in the same way everywhere ." "Just showing pictures of people being born and dying tells us, literally, nothing."[41]

Many other noteworthy reactions, both positive and negative, have been proffered in social/cultural studies and as part of artistic and historical texts. The earliest critics of the show were, ironically, photographers, who felt that Steichen had downplayed individual talent and discouraged the public from accepting photography as art. The show was the subject of an entire issue of Aperture; "The Controversial 'Family of Man'"[42] Walker Evans disdained its "human familyhood [and] bogus heartfeeling"[43] Phoebe Lou Adams complained that "If Mr. Steichen's well-intentioned spell doesn't work, it can only be because he has been so intent on [Mankind's] physical similarities that...he has utterly forgotten that a family quarrel can be as fierce as any other kind."[44]

Some critics complained that Steichen merely transposed the magazine photo-essay from page to museum wall; in 1955 Rollie McKenna likened the experience to a ride through a funhouse,[45] while Russell Lynes in 1973 wrote that Family of Man "was a vast photo-essay, a literary formula basically, with much of the emotional and visual quality provided by sheer bigness of the blow-ups and its rather sententious message sharpened by juxtaposition of opposites — wheat fields and landscapes of boulders, peasants and patricians, a sort of 'look at all these nice folks in all these strange places who belong to this family.'"[46] Jacob Deschin, photography critic for The New York Times , wrote, "the show is essentially a picture story to support a concept and an editorial achievement rather than an exhibition of photography."[47]

From an optic of struggle,[48] echoing Barthes, Susan Sontag in On Photography accused Steichen of sentimentalism and oversimplification: ' ... they wished, in the 1950s, to be consoled and distracted by a sentimental humanism. ... Steichen's choice of photographs assumes a human condition or a human nature shared by everybody." Directly quoting Barthes, without acknowledgement,[21] she continues; "By purporting to show that individuals are born, work, laugh, and die everywhere in the same way, "The Family of Man" denies the determining weight of history - of genuine and historically embedded differences, injustices, and conflicts.'[49]

Others attacked the show as an attempt to paper over problems of race and class, including Christopher Phillips, John Berger, and Abigail Solomon-Godeau, who in her 2004 essay, while describing herself as among "those who intellectually came of age as postmodernists, poststructuralists, feminists, Marxists, antihumanists, or, for that matter, atheists, this little essay of Barthes's efficiently demonstrated the problem — indeed the bad faith — of sentimental humanism", concedes that "as photography exhibitions go, it is perhaps the ultimate "bad object" for progressives or critical theorists", but "good to think with.".[50] Many of these critics, including Solomon-Godeau who openly admits it,[50] it should be noted, had not viewed the exhibition but were working from the published catalogue which notably excludes the image of the atomic explosion.[21][8]

While The Family of Man was being exhibited there at its last venue in 1959 several pictures were torn down in Moscow by the Nigerian student Theophilus Neokonkwo. An Associated Press report of the time[51] suggests that his actions were in a protest at colonialist attitudes to black races[52]

Conversely, other critics defended the exhibition, referring to the political and cultural environment in which it was staged. Among these were Fred Turner,[11] Eric J. Sandeen,[8] Blake Stimson[53] and Walter L. Hixson.[54] Most recently, a compilation of essays[55] by contemporary critics supported by newly translated writings contemporary to the exhibition's appearances collected and edited by Gerd Hurm, Anke Reitz and Shamoon Zamir presents a revised reading of Steichen's motivations and audience reactions, and a reassessment of the validity of Roland Barthes' influential criticism in "La grande famille des hommes" in his Mythologies.

Tributes, sequels and critical revisions

In the years since The Family of Man, several exhibitions stemmed from projects directly inspired by Steichen's work and others were presented in opposition to it. Still others were alternative projects offering new thoughts on the themes and motifs presented in 1955. These serve to represent artists', photographers' and curators' responses to the exhibition beside those of the cultural critics, and to track the evolution of reactions as societies and their self-images change.

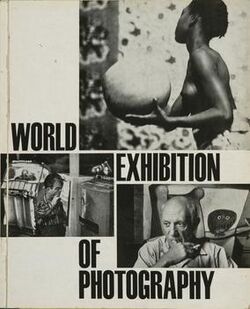

World Exhibition of Photography

Following The Family of Man by 10 years, the 1965 Weltausstellung der Fotographie (World Exhibition of Photography) was based on an idea by Karl Pawek and, supported by the German magazine Stern, toured the world.[56] It presented 555 photographs by 264 authors from 30 countries, outweighing the numbers in Steichen's exhibition. In the preface to the catalogue entitled 'Die humane Kamera' ('The human camera'), Heinrich Boll wrote: "There are moments in which the meaning of a landscape and its breath become felt in a photograph. The portrayed person becomes familiar or a historical moment happens in front of the lens; a child in uniform, women who search the battlefield for their dead. They are moments in which crying is more than private as it becomes the crying of mankind. Secrets are not revealed, the secret about human existence becomes visible."

The exhibition, wrote Pawek, 'would like to keep alive the spirit of Edward Steichen's wonderful ideas and of his memorable collection, The Family of Man.'.[57] His exhibition posed the question 'Who is Man?' in 42 topics. It focussed on issues that were sublimated in The Family of Man by the idea of universal brotherhood between men and women of different races and cultures. Racism, which in Steichen's show was represented by a lynching scene (replaced in the European showings by an enlargement of the famous picture of the Nürnberg trial), is confronted in the Weltausstellung der Fotographie section VIII Das Missverständnis mit der Rasse (Misunderstandings about Race) by the black man in the photograph by Gordon Parks who seems to view from his window two scenes of attacks on black people (photographed by Charles Moore). Another photograph by Henri Leighton shows two children walking together in public holding hands, one black, one white. Though reference to the content of the older exhibition in the new is evident, the unifying idealism of The Family of Man is here replaced with a much more fragmented and sociological one.[58] The exhibition met with rejection by the press and functionaries in the photographic profession in Germany and Switzerland, and was described by Fritz Kempe, board member of a prominent photo company, as "tasty fodder to stimulate the aggressive instincts of semi—intellectual young men.".[59] Nevertheless, it went on to tour 261 art museums in 36 countries and was visited by 3,500,000 people.

2nd World Exhibition of Photography

In 1968, a second Weltausstellung der Fotographie (2nd World Exhibition of Photography) was devoted to images of women[60] with 522 photographs from 85 countries by 236 photographers, of whom barely 10% were female (compared to 21% for The Family of Man), though there is evidence of the effect of feminist consciousness in images of men in domestic environments cleaning, cooking and tending babies. In his introduction, Karl Pawek writes: "I had approached the first exhibition with my entire theological, philosophical and sociological equipment. 'What is Man'?; the question had to awaken ideological ideas. [...] I also operated from a philosophical point of view when presenting the[se] photos. As far as woman was concerned, the theme of the second exhibition, I knew nothing. There I was, without any philosophy about woman. Perhaps woman is not a philosophical theme. Perhaps there is only mankind, and woman is something unique and special? Thus I could only hold on to what was concrete in the pictures."

The Family of Children

UNESCO named 1977 The Year of Children and in response the book The Family of Children was dedicated to Steichen by editor Jerry Mason, and imitated the original catalogue in its layout, in the use of quotations and in the colours used on the cover.[61] As for Steichen's show there was a call-out for imagery but 300,000 entries were received compared to the 4 million at the MoMA show, resulting in a selection of 377 photos by 218 participants from 70 countries.

The Family of Man 1955-1984

Independent curator Marvin Heiferman's The Family of Man 1955·1984 was a floor to ceiling collage of over 850 images and texts from magazines. newspapers and the art world shown in 1984 at PSI, The Institute for Art and Urban Resources Inc. (now MoMA PS1) Long Island City N.Y.[62] Abigail Solomon-Godeau described it as a reexamination of the themes of the 1955 show and critique of Steichen's arrangement of them into a 'spectacle';

...a grab bag of imagery and publicity ranging from baby food and sanitary napkin boxes to hard-core pornography, from detergent boxes to fashion photography, a cornucopia of consumer culture much of which, in one way or another, could be seen to engage the same themes purveyed in The Family of Man. In a certain sense, Heifferman's [sic] riposte to Steichen's show made the useful connection between the spectacle of the exhibition and the spectacle of the commodity, suggesting that both must be understood within the framing context of late capitalism.[36]

Oppositions: We are the world, you are the third world

In 1990 the second Rotterdam Biennale lead exhibition was Oppositions: We are the world, you are the third world - Commitment and cultural identity in contemporary photography from Japan, Canada. Brazil, the Soviet Union and the Netherlands[63] The cover of the catalogue imitates the layout and colour of the original but replaces the famous image of the little flute player by Eugene Harris with six images, four photographs of young women from different cultural backgrounds and two excerpts from paintings. In the exhibit scenes of a endangered ecology and the threat to cultural identity in the global village predominate, but there are intimations that nature and love may prevail, despite everything artificial that surrounds it, notably so in family life.[58]

New Relations. The Family of Man Revisited

In 1992 the American critic and photographer Larry Fink published a collection of photographs under the heading of New Relations. The Family of Man Revisited in the Photography Center Quarterly.[64] His approach updated Steichen's vision by integrating aspects of human existence which Steichen had omitted both because of his wish for coherence and of his innermost convictions. Fink provides only the following commentary: "Rather than a fawn pretence to anthropological/sociologic analysis of the events depicted; rather than categorise and choose democratically for social relevance.| took the path of least resistance and most reward. I simply selected quality images with the belief that the path of strong visual energies would visit equal strong social presences". He concludes:

The show is a compendium of visual hints. It is not an answer or even a full question, but cognitive clues....

family, nation, tribe, community: SHIFT

In September/October 1996 the NGBK (Neue Gesellschaft fur Bildende kunst Berlin- New Society for the Visual Arts Berlin) in the context of 'Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW)' (House of World Cultures Berlin) conceived and organised the project family, nation, tribe, community: SHIFT with direct reference to the historical MoMA exhibition. In the catalogue, five authors; Ezra Stoller, Max Kozloff, Torsten Neuendorff, Bettina Allamoda and Jean Back analyse and comment on the historical model and twenty-two artists offer individual approaches around the following themes: Universalism/Separatism, Family/Anti-family, Individualisation, Common Strategies, Differences. The works are predominantly from artist photographers rather than photojournalists; Bettina Allamoda, Aziz + Cucher, Los Carpinteros, Alfredo Jaar, Mike Kelley, Edward and Nancy Reddin Kienholz, Lovett/Codagnone, Loring McAlpin, Christian Philipp Müller, Anna Petrie, Martha Rosler, Lisa Schmitz, STURTEVANT, Mitra Tabizian and Andy Golding, Wolfgang Tillmans, Danny Tisdale, Lincoln Tobler, and David Wojnarowicz reflect major contemporary issues: identity, the information crisis, the illusion of leisure, and ethics. In his introduction to the exhibition, Frank Wagner writes that Steichen had offered a vision of an harmonious, neat and highly structured world which, in reality, was complex, often unintelligible and even contradictory, but by contrast, this Berlin exhibition highlights 'first' and 'third' world tensions and is eager to concentrate on a variety of attitudes.[65]

The 90s: A Family of Man?

The following year Enrico Lunghi directed the exhibition The 90s: A Family of Man?: images of mankind in contemporary art, held 02.10.-30.11.1997 in Luxembourg, Steichen's birthplace and by then the repository of the archive of a full version of his The Family of Man. Aside from their understanding of Steichen's efforts to present commonalities amongst the human race, curators Paul di Felice and Pierre Stiwer interpret Steichen's show as an effort to make content of Museum of Modern Art accessible to the public in an era when it was regarded as the elitist supporter of 'incomprehensible' abstract art. They point to their predecessor's success in having his show embraced by a record audience and emphasise that dissenting voices of criticism were heard only amongst 'intellectuals'. However, Steichen's success, they caution, was to manipulate the message of his selected imagery; 'After all,' they write, 'wasn't he the artistic director of Vogue and Vanity Fair ... ?'.[66] They proclaim their desire to retain the exhibiting artists' 'autonomy' while not posing their work as the antithesis of Steichen's concept, but to respect, and echo, its arrangement while 'raising questions' as indicated by the question mark in their quotation of the original title. The exhibition and catalogue 'quote' from Steichen, setting pages of the book of his exhibition with their quotations around groupings of images (in monochrome) beside the works of contemporary artists (predominantly in colour) collected in themes used in the original, though the correlation fails for some contemporary ideas, which digital imaging, installation and montage works effectively convey. The thirty-five artists include Christian Boltanski, Nan Goldin, Inez van Lamsweerde, Orlan and Wolfgang Tillmans.

Reconsidering The Family of Man

The Photographic Society of America (PSA) drew on their archives to stage Reconsidering The Family of Man during April and May 2012. They based the display on the concept of Steichen's original exhibit but concentrated on his sub-theme of the passage from birth to death. From the close to 5,000 photographs in the PSA collection, a selection of 50 was made for their show.One work in common was Ansel Adams' Mount Williamson from Manzanar which in The Family of Man was presented at mural scale, while the PSA used a vintage,11 "x 14" Adams print from their collection, displaying it wilh a first edition copy of The Family of Man publication opened to a double-page spread of Adams photograph.[67]

Permanent installation, Chateau Clervaux, Luxembourg

The permanent installation of the exhibition today at Chateau Clervaux in Luxembourg follows the layout of the inaugural exhibition at MoMA in order to recreate the original viewing experience, though necessarily it is adapted to the unique space of two floors of the restored Castle. Since the 2013 restoration it now incorporates a library (that includes some of the catalogues of the sequel exhibitions above) and contextualises The Family of Man with historical material and interpretation.[68]

Cultural references to The Family of Man

- Karl Dallas' song, The Family of Man, also recorded by The Spinners and others, was written in 1955, after Dallas saw the exhibition.[69]

- In 1962, Instytut Mikołowski published Komentarze do fotografii. The Family of Man by Polish poet Witold Wirpsza (1918–1985), a commentary on individual photographs and selected displays from the exhibition.[70][21]

References

- ↑ The Family of Man is "one of the most ambitious and challenging projects, photography has ever attempted. It was conceived as a mirror of the universal elements and cmotions in the everydayness of life and demonstrates that the art of photography is a dynamic process of giving form to ideas and of explaining man to man". Steichen quoted in United States. American Embassy. Office of Public Affairs; University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (1956), Visitors' reactions to the "Family of man" exhibit, American Embassy, Office of Public Affairs, http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/2993760, retrieved 19 October 2014

- ↑ Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man: The greatest photographic exhibition of all time—503 pictures from 68 countries—created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art. New York, Maco Magazine Corporation, 1955.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2015-02-12. https://web.archive.org/web/20150212133648/http://www.steichencollections.lu/en/The-Family-of-Man. Retrieved 2015-02-12.

- ↑ "Clervaux - cité de l'image -". http://www.clervauximage.lu/index.php?id=8;lang=en;event=1.

- ↑ "Family of Man". UNESCO Memory of the World Programme. 2008-05-16. http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=23246&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html. Retrieved 2009-12-14.

- ↑ "Edward Steichen at The Family of Man, 1955". MoMA. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20111125045308/http://www.moma.org/learn/resources/archives/archives_highlights_06_1955. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- ↑ founded in 1952 to develop and tour circulating exhibitions, including United States Representations at international exhibitions and festivals, one-person shows, and group exhibitions. Since the founding of the International Program, MoMA exhibitions have had hundreds of showings around the world. MoMa Archives

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Eric J. Sandeen, Picturing an Exhibition: "The Family of Man" and 1950s America (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 White, Ralph K. (Winter 1959). "Reactions to Our Moscow Exhibit: Voting Machines and Comment Books". The Public Opinion Quarterly. 4 23: 461–470. doi:10.1086/266900.

- ↑ Edward., Steichen,. Steichen : a life in photography. ISBN 9781135462840. OCLC 953971378. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/953971378.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Turner, Fred (2012) 'The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America' in Public Culture 24:1 Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/08992363-1443556

- ↑ "Family of Man, Exhibition Installation at Museum of Modern Art by Paul Rudolph". Interiors (April 1955): 114-17.

- ↑ Paul, Rudolph (14 August 2018). "Family of Man exhibit, Museum of Modern Art, New York City. Plan". https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2004675273/.

- ↑ Paul Rudolph, interview by Mary Anne Staniszewski, December 27, 1993, quoted in Staniszewski, Mary Anne & Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) (1998). The power of display : a history of exhibition installations at the Museum of Modern Art. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts p.240

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Katherine Hoffman (2005) Sowing the seeds/setting the stage: Steichen, Stieglitz and The Family of Man , History of Photography, 29:4, 320-330, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2005.10442814

- ↑ Osman, C. (1991). LETTERS. The British Journal of Photography, 139(6831), 9.

- ↑ Sollors, Werner (2018) "The Family of Man: Looking at the Photographs Now and Remembering a Visit in the 1950s" in Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3

- ↑ 'Portfolio', 357, Eric J. Sandeen, 'The International Reception of The Family of Man, History of Photography 29, no. 4, (2005)

- ↑ Ralph L. Harley, Jr., 'Edward Steichen's Modernist Art-Space', History ofPhotography 14:1 (Spring 1990), 1.

- ↑ Steichen, E. (1963). A life in photography. Garden City, N.Y: Doubleday.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, p. 11, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3

- ↑ Steichen, Edward; Steichen, Edward, 1879-1973, (organizer.); Sandburg, Carl, 1878-1967, (writer of foreword.); Norman, Dorothy, 1905-1997, (writer of added text.); Lionni, Leo, 1910-1999, (book designer.); Mason, Jerry, (editor.); Stoller, Ezra, (photographer.); Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) (1955). The family of man : the photographic exhibition. Published for the Museum of Modern Art by Simon and Schuster in collaboration with the Maco Magazine Corporation. https://trove.nla.gov.au/work/10809600.

- ↑ Parr, Martin & Badger, Gerry (2006). The photobook : a history. vol. 2. Phaidon, London ; New York

- ↑ Mason was previously editor of This Week (1948—1952), then editorial director of Popular Publications and editor of Argosy magazine (1948—1952 [1]

- ↑ Stimson, Blake (2006). The pivot of the world : photography and its nation. MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts

- ↑ Museum of Modern Art, New York. The Family of Man: The greatest photographic exhibition of all time—503 pictures from 68 countries—created by Edward Steichen for the Museum of Modern Art. New York, Maco Magazine Corporation, 1955.

- ↑ Withey, S. B. 1954. Survey of Public Knowledge and Attitudes Concerning Civil Defense. Ann Arbor: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan.

- ↑ Orvell, Miles 'Et in Arcadia Ego: The Family of Man as a Cold War Pastoral' in Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN:978-1-78672-297-3, 191-209

- ↑ Zamir, Shamoon, 'Structures of Rhyme, Forms of Participation: The Family of Man as Exhibition', in Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN:978-1-78672-297-3, 133-156

- ↑ MoMA bookshop site

- ↑ Jay, Bill (1989) "The Family of Man A Reappraisal of 'The Greatest Exhibition of All Time'. Insight, Bristol Workshops in Photography, Rhode Island, Number 1, 1989.

- ↑ Kristen Gresh (2005) The European roots of The Family of Man, History of Photography, 29:4, 331-343, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2005.10442815

- ↑ Turner, Fred (2012). 'The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America', in Public Culture 24:1 Duke University Press doi:10.1215/08992363-1443556

- ↑ Dorothea Lange, letter, January 16, 1953, quoted in Szarkowski, "The Family of Man," 24.

- ↑ Alise Tlfentale (2015) in Šelda Pukīte (editor) and Latvian National Museum of Art and Luxembourg National Museum of History and Art. Edvards Steihens. Fotografija: Izstades katalogs (Edward Steichen. Photography: Exhibition catalogue). Neputns Publishing House and Latvian National Museum of Art

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Solomon-Godeau, Abigail; Parsons, Sarah (Sarah Caitlin), 1971-, (editor.) (2017), Photography after photography : gender, genre, history, Durham Duke University Press, p. 57, ISBN 978-0-8223-6266-1

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Gresh, Kristen. 2005. "The European Roots of 'The Family of Man' ". History of Photography 29, (4): 331-343

- ↑ http://www.moma.org/momaorg/shared/pdfs/docs/archives/ExhMasterChecklists/MoMAExh_0569_MasterChecklist.pdf

- ↑ Edward Steichen, "Photography: Witness and Recorder of History," Wisconsin Magazine of History 41, no. 3 (1958): 160.

- ↑ Barbara Morgan, "The Theme Show: A Contemporary Exhibition Technique," in n.a., "The Controversial Family of Man," Aperture 3, no. 2 (1955)

- ↑ Roland Barthes, "La grande famille des hommes" ("The Great Family of Man"), in Mythologies (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1957), 173–76; English translation edition: Roland Barthes, "The Great Family of Man," Mythologies, translated by Annette Lavers (St Albans, Hertfordshire: Picador, 1976), 100-102.

- ↑ Aperture, vol. 3, no. 2, 1955

- ↑ Walker Evans, "Robert Frank," US Camera 1958 (New York: US Camera Publishing Corporation, 1957), 90.

- ↑ Phoebe Lou Adams, "Through a Lens Darkly." Atlantic Monthly, no. 195 (April 1955), p. 72

- ↑ "Good photographs speak for themselves. Steichen would be the first to agree, but somehow he and Paul Rudolf (sic), a gifted Florida architect, designed a display so elaborate that the photographs become less important than the methods of displaying them [...] Pictures of children throughout the world playing ring-around-a-rosy are contorted into trapezoids and mounted on a circular metal construction. In another instance a man is chopping wood high in a tree top. This undistinguished photograph has been mounted horizontally over the spectator's head. To see it properly he has to get in the same position as the photographer who took the picture, on his back! [...] Photographs grow from pink and lavender poles, dangle from the ceiling, lie on the floor, protrude from the wall. Some, happily, just hang. In case the point has not yet been made, toward the end of the exhibit there is a group of nine portraits arranged around---yes, a mirror. Alongside is a quote from Bertrand Russell. " ... for the majority it is a slow torture of disease and disintegration." wrote Rollie McKenna, in his review of "The Family of Man," New Republic, 14 March 1955, p. 30.

- ↑ Russell Lynes, Good Old Modern: An Intimate Portrait of the Museum of Modern Art (New York: Atheneum, 1973), 325.

- ↑ Jacob Deschin quoted in Szarkowski, John; Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.) (1978), Mirrors and windows : American photography since 1960, Museum of Modern Art ; Boston : distributed by New York Graphic Society, p. 16, ISBN 978-0-87070-475-8

- ↑ Lopate, Phillip (2009). Notes on Sontag. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. ; Woodstock p.205

- ↑ Sontag, S. (1977) On Photography. Penguin (Harmondsworth), UK

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Abigail Solomon-Godeau, "'The Family of Man': Den Humanismus für ein postmodernes Zeitalter aufpolieren" ("'The Family of Man': Refurbishing Humanism for a Postmodern Age"), in "The Family of Man," 1955–2001: Humanismus und Postmoderne; eine Revision von Edward Steichens Fotoausstellung ("The Family of Man," 1955–2001: Humanism and Postmodernism; a Reappraisal of the Photo Exhibition by Edward Steichen), ed. Jean Back and Viktoria Schmidt- Linsenhoff (Marburg, Germany: Jonas, 2004), 28–55

- ↑ "Student Arrested for Slashing Photographs in THE FAMILY OF MAN in Moscow." The Associated Press report read: “Moscow, August 6, All. A medical student from Nigeria has been arrested by Soviet Police for slashing four photographs in the U.S. Exhibition. The Nigerian was arrested Wednesday after he cut up pictures from the photographic series, 'The Family of Man’ which he clearly disliked. One picture showed an African dance. Another was a large tattooed face. A third was a hunter holding up a deer. The fourth showed African lips drinking water from a gourd. Exhibition officials withdrew the damaged pictures and said an effort will be made to restore them.”

- ↑ Kaplan, Louis (2005), American exposures : photography and community in the twentieth century, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-4569-5

- ↑ Blake Stimson (2006), The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ↑ Parting the Curtain: Propaganda, Culture and the Cold War, 1945 – 1961 (St Martin's Press: New York, 1997), p. 83.

- ↑ Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-1-78672-297-3

- ↑ Becker, Hellmut (1965). Zur "Weltausstellung der Photographie". : Ansprache zur Eröffnung der Weltausstellung der Photographie in der Akademie der Künste am 11. Juli 1965. Akademie der Künste, Berlin

- ↑ Pawek, K. The Language of Photography: The Methods of this Exhibition. In World Exhibition of Photography (1964) & Pawek, Karl & Wilhelm, Peter Jürgen (1964). World Exhibition of Photography : 555 photos by 264 photographers from 30 countries on the theme What is man?. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Jean Back (1997) Identities and Differences: Four Historical and Contemporary Approaches Towards The Family Of Man. In Di Felice, Paul & Stiwer, Pierre & Galerie Nei Liicht & Casino Luxembourg (1997). The 90's : a family of man? : images de l'homme dans l'art contemporain. Casino Luxembourg : Café-Crème, Luxembourg

- ↑ Karl Pawek in introduction to Stern (Hamburg) (1968). Die Frau : 2. Weltausstellung der Photographie, 522 Photos aus 85 Ländern von 236 Photographen. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg

- ↑ Stern (Hamburg) (1968). Die Frau : 2. Weltausstellung der Photographie, 522 Photos aus 85 Ländern von 236 Photographen. Gruner + Jahr, Hamburg

- ↑ Mason, Jerry (1977). The Family of children. Grosset & Dunlap, New York

- ↑ Shelley Rice: photographic installation, an overview. In sfcamerawork quarterly, v.12 n.1 Spring 1985

- ↑ 1990). Oppositions : commitment and cultural identity in contemporary photography from Japan, Canada, Brazil, the Soviet Union and the Netherlands. Uitgeverij, Rotterdam

- ↑ Center Quarterly (Woodstock, New York: Photography Center) no. 50 (1991). "It's All Relative" [re: Larry Fink, "New Relations The Family of Man Revisited": 4-17

- ↑ Family, Nation, Tribe, Community SHIFT: Zeitgenössische künstlerische Konzepte im Haus der Kulturen der Welt (Berlin: Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst HGBK, 1996)

- ↑ Paul di Felice, Pierre Stiwer (1997) Catalogue réalisé à l'occasion de L'Exposition "The 90s: A Family of Man?" au Casino Luxembourg, Forum d'art contemporain et à la Galerie Nei Liicht de Dudelange en octobre-novembre I997, co-édité par Casino Luxembourg-Forum d'art contemporain et Café-Créme absl., traductions Marie-Jo Decker, Jean-Paul Junck, Pierre Stiwer. Imprimerie Centrale Luxembourg. Dépôt légal octobre I997 ISBN:2-919893-07-6

- ↑ Burris, J. (2012, 04). The PSA print collection and reconsidering the family of man at artspace. PSA Journal, 78, 18-21.

- ↑ Anke Reitz (2018) 'Re-exhibiitng The Family of Man: Luxembourg 2013', in Hurm, Gerd, 1958-, (editor.); Reitz, Anke, (editor.); Zamir, Shamoon, (editor.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN:978-1-78672-297-3

- ↑ Dallas, Karl. "The Family of Man". Bandcamp. https://karldallas.bandcamp.com/track/the-family-of-man. Retrieved 26 September 2016.

- ↑ Witold Wirpsza (1962) Komentarze do fotografii. Wydawnictwo Literackie.

Further reading

- Gresh, Kristen. 2005. "The European Roots of 'The Family of Man' ". History of Photography 29, (4): 331-343.

- Steichen, Edward (2003) [1955]. The Family of Man. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. ISBN:0-87070-341-2

- Sandeen, Eric J. Picturing An Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950s America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995.

- Stimson, Blake (2006) The Pivot of the World: Photography and Its Nation. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- Turner, Fred (2012) 'The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America' in Public Culture 24:1 Duke University Press. doi:10.1215/08992363-1443556

- Hurm, Gerd, (ed.); Reitz, Anke, (ed.); Zamir, Shamoon, (ed.) (2018), The family of man revisited : photography in a global age, London I.B.Tauris, ISBN:978-1-78672-297-3

External links

- Photographs documenting the complete original exhibition at MoMA

- Official website of the Museum The Family of Man, Clervaux, Luxembourg

- CarlSandburg.net: a Research Website for Sandburg Studies