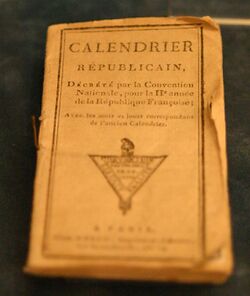

French Republican Calendar

The French Republican calendar (French: calendrier républicain français), also commonly called the French Revolutionary calendar (calendrier révolutionnaire français), was a calendar created and implemented during the French Revolution , and used by the French government for about 12 years from late 1793 to 1805, and for 18 days by the Paris Commune in 1871. The revolutionary system was designed in part to remove all religious and royalist influences from the calendar, and was part of a larger attempt at decimalisation in France (which also included decimal time of day, decimalisation of currency, and metrication). It was used in government records in France and other areas under French rule, including Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Malta, and Italy.

Overview and origins

Precursor

Sylvain Maréchal, prominent anticlerical atheist, published the first edition of his Almanach des Honnêtes-gens (Almanac of Honest People) in 1788.[1] On pages 14–15 appears a calendar, consisting of twelve months. The first month is "Mars, ou Princeps" (March, or First), the last month is "Février, ou Duodécembre" (February, or Twelfth). (The months of September [meaning "the seventh"] through December [meaning "the tenth"] are already numeric names, although their meanings do not match their positions in either the Julian or the Gregorian calendar since the Romans changed the first month of a year from March to January.) The lengths of the months are the same; however, the 10th, 20th, and 30th are singled out of each month as the end of a décade (group of ten). Individual days were assigned, instead of to the traditional saints, to people noteworthy for mostly secular achievements; 25 December is assigned to both Jesus and Newton.[citation needed]

Later editions of the almanac would switch to the Republican Calendar.[citation needed]

History

The days of the French Revolution and Republic saw many efforts to sweep away various trappings of the ancien régime (the old feudal monarchy); some of these were more successful than others. The new Republican government sought to institute, among other reforms, a new social and legal system, a new system of weights and measures (which became the metric system), and a new calendar. Amid nostalgia for the ancient Roman Republic, the theories of the Enlightenment were at their peak, and the devisers of the new systems looked to nature for their inspiration. Natural constants, multiples of ten, and Latin as well as Ancient Greek derivations formed the fundamental blocks from which the new systems were built.

The new calendar was created by a commission under the direction of the politician Charles-Gilbert Romme seconded by Claude Joseph Ferry and Charles-François Dupuis. They associated with their work the chemist Louis-Bernard Guyton de Morveau, the mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange, the astronomer Joseph Jérôme Lefrançois de Lalande, the mathematician Gaspard Monge, the astronomer and naval geographer Alexandre Guy Pingré, and the poet, actor and playwright Fabre d'Églantine, who invented the names of the months, with the help of André Thouin, gardener at the Jardin des Plantes of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris. As the rapporteur of the commission, Charles-Gilbert Romme presented the new calendar to the Jacobin-controlled National Convention on 23 September 1793, which adopted it on 24 October 1793 and also extended it proleptically to its epoch of 22 September 1792. It is because of his position as rapporteur of the commission that the creation of the republican calendar is attributed to Romme.[2]

The calendar is frequently named the "French Revolutionary Calendar" because it was created during the Revolution, but this is moderate of a misnomer. Indeed, there was initially a debate as to whether the calendar should celebrate the Great Revolution, which began in July 1789, or the Republic, which was established in 1792.[3] Immediately following 14 July 1789, papers and pamphlets started calling 1789 year I of Liberty and the following years II and III. It was in 1792, with the practical problem of dating financial transactions, that the legislative assembly was confronted with the problem of the calendar. Originally, the choice of epoch was either 1 January 1789 or 14 July 1789. After some hesitation the assembly decided on 2 January 1792 that all official documents would use the "era of Liberty" and that the year IV of Liberty started on 1 January 1792. This usage was modified on 22 September 1792 when the Republic was proclaimed and the Convention decided that all public documents would be dated Year I of the French Republic. The decree of 2 January 1793 stipulated that the year II of the Republic began on 1 January 1793; this was revoked with the introduction of the new calendar, which set 22 September 1793 as the beginning of year II. The establishment of the Republic was used as the epochal date for the calendar; therefore, the calendar commemorates the Republic, not the Revolution. In France, it is known as the calendrier républicain as well as the calendrier révolutionnaire.

French coins of the period naturally used this calendar. Many show the year (French: an) in Arabic numbers, although Roman numerals were used on some issues. Year 11 coins typically have a "XI" date to avoid confusion with the Roman "II".

The French Revolution is usually considered to have ended with the coup of 18 Brumaire, Year VIII (9 November 1799), the coup d'état of Napoleon Bonaparte against the established constitutional regime of the Directoire.

The Concordat of 1801 re-established the Roman Catholic Church as an official institution in France, although not as the state religion of France. The concordat took effect from Easter Sunday, 28 Germinal, Year XI (8 April 1802); it restored the names of the days of the week to the ones from the Gregorian Calendar, and fixed Sunday as the official day of rest and religious celebration.[4] However, the other attributes of the republican calendar, the months, and years, remained as they were.

The French Republic ended with the coronation of Napoleon I as Empereur des Français (Emperor of the French) on 11 Frimaire, Year XIII (2 December 1804), but the republican calendar would remain in place for another year. Napoleon finally abolished the republican calendar with effect from 1 January 1806 (the day after 10 Nivôse Year XIV), a little over twelve years after its introduction. It was, however, used again briefly during the short period of the Paris Commune, 6–23 May 1871 (16 Floréal–3 Prairial Year LXXIX).

Calendar design

Years appear in writing as Roman numerals (usually), with epoch 22 September 1792, the beginning of the "Republican Era" (the day the French First Republic was proclaimed, one day after the Convention abolished the monarchy). As a result, Roman Numeral I indicates the first year of the republic, that is, the year before the calendar actually came into use. By law, the beginning of each year was set at midnight, beginning on the day the apparent autumnal equinox falls at the Paris Observatory.

There were twelve months, each divided into three ten-day weeks called décades. The tenth day, décadi, replaced Sunday as the day of rest and festivity. The five or six extra days needed to approximate the solar or tropical year were placed after the months at the end of each year and called complementary days. This arrangement was an almost exact copy of the calendar used by the Ancient Egyptians, though in their case the beginning of the year was marked by summer solstice rather than autumn equinox.

A period of four years ending on a leap day was to be called a "Franciade". The name "Olympique" was originally proposed[5] but changed to Franciade to commemorate the fact that it had taken the revolution four years to establish a republican government in France.[6]

The leap year was called Sextile, an allusion to the "bissextile" leap years of the Julian and Gregorian calendars, because it contained a sixth complementary day.

Decimal time

Each day in the Republican Calendar was divided into ten hours, each hour into 100 decimal minutes, and each decimal minute into 100 decimal seconds. Thus an hour was 144 conventional minutes (more than twice as long as a conventional hour), a minute was 86.4 conventional seconds (44% longer than a conventional minute), and a second was 0.864 conventional seconds (13.6% shorter than a conventional second).

Clocks were manufactured to display this decimal time, but it did not catch on. Mandatory use of decimal time was officially suspended 7 April 1795, although some cities continued to use decimal time as late as 1801.[7]

The numbering of years in the Republican Calendar by Roman numerals ran counter to this general decimalization tendency.

Months

The Republican calendar year began the day the autumnal equinox occurred in Paris, and had twelve months of 30 days each, which were given new names based on nature, principally having to do with the prevailing weather in and around Paris.

- Autumn:

- Vendémiaire (from French vendange, derived from Latin vindemia, "grape harvest"), starting 22, 23, or 24 September

- Brumaire (from French brume, "mist"), starting 22, 23, or 24 October

- Frimaire (From French frimas, "frost"), starting 21, 22, or 23 November

- Winter:

- Nivôse (from Latin nivosus, "snowy"), starting 21, 22, or 23 December

- Pluviôse (from French pluvieux, derived from Latin pluvius, "rainy"), starting 20, 21, or 22 January

- Ventôse (from French venteux, derived from Latin ventosus, "windy"), starting 19, 20, or 21 February

- Spring:

- Germinal (from French germination), starting 20 or 21 March

- Floréal (from French fleur, derived from Latin flos, "flower"), starting 20 or 21 April

- Prairial (from French prairie, "meadow"), starting 20 or 21 May

- Summer:

- Messidor (from Latin messis, "harvest"), starting 19 or 20 June

- Thermidor (or Fervidor*) (from Greek thermon, "summer heat"), starting 19 or 20 July

- Fructidor (from Latin fructus, "fruit"), starting 18 or 19 August

*Note: On many printed calendars of Year II (1793–94), the month of Thermidor was named Fervidor (from Latin fervens, "hot").

Most of the month names were new words coined from French, Latin, or Greek. The endings of the names are grouped by season. "Dor" means "giving" in Greek.[8]

In Britain, a contemporary wit mocked the Republican Calendar by calling the months: Wheezy, Sneezy and Freezy; Slippy, Drippy and Nippy; Showery, Flowery and Bowery; Hoppy, Croppy and Poppy.[9] The Scottish historian Thomas Carlyle suggested somewhat more serious English names in his 1837 work The French Revolution: A History,[8] namely Vintagearious, Fogarious, Frostarious, Snowous, Rainous, Windous, Buddal, Floweral, Meadowal, Reapidor, Heatidor, and Fruitidor. Like the French originals, they are neologisms suggesting a meaning related to the season.

Ten days of the week

The month is divided into three décades or "weeks" of ten days each, named simply:

- primidi (first day)

- duodi (second day)

- tridi (third day)

- quartidi (fourth day)

- quintidi (fifth day)

- sextidi (sixth day)

- septidi (seventh day)

- octidi (eighth day)

- nonidi (ninth day)

- décadi (tenth day)

Décades were abandoned in Floréal an X (April 1802).[10]

Rural Calendar

The Catholic Church used a calendar of saints, which named each day of the year after an associated saint. To reduce the influence of the Church, Fabre d'Églantine introduced a Rural Calendar in which each day of the year had a unique name associated with the rural economy, stated to correspond to the time of year. Every décadi (ending in 0) was named after an agricultural tool. Each quintidi (ending in 5) was named for a common animal. The rest of the days were named for "grain, pasture, trees, roots, flowers, fruits" and other plants, except for the first month of winter, Nivôse, during which the rest of the days were named after minerals.[11][12]

Our starting point was the idea of celebrating, through the calendar, the agricultural system, and of leading the nation back to it, marking the times and the fractions of the year by intelligible or visible signs taken from agriculture and the rural economy. (...)As the calendar is something that we use so often, we must take advantage of this frequency of use to put elementary notions of agriculture before the people – to show the richness of nature, to make them love the fields, and to methodically show them the order of the influences of the heavens and of the products of the earth.

The priests assigned the commemoration of a so-called saint to each day of the year: this catalogue exhibited neither utility nor method; it was a collection of lies, of deceit or of charlatanism.

We thought that the nation, after having kicked out this canonised mob from its calendar, must replace it with the objects that make up the true riches of the nation, worthy objects not from a cult, but from agriculture – useful products of the soil, the tools that we use to cultivate it, and the domesticated animals, our faithful servants in these works; animals much more precious, without doubt, to the eye of reason, than the beatified skeletons pulled from the catacombs of Rome.

So we have arranged in the column of each month, the names of the real treasures of the rural economy. The grains, the pastures, the trees, the roots, the flowers, the fruits, the plants are arranged in the calendar, in such a way that the place and the day of the month that each product occupies is precisely the season and the day that Nature presents it to us.

Autumn

Winter

Spring

Summer

Complementary days

Five extra days – six in leap years – were national holidays at the end of every year. These were originally known as les sans-culottides (after sans-culottes), but after year III (1795) as les jours complémentaires:

- 1st complementary day: La Fête de la Vertu, "Celebration of Virtue", on 17 or 18 September

- 2nd complementary day: La Fête du Génie, "Celebration of Talent", on 18 or 19 September

- 3rd complementary day: La Fête du Travail, "Celebration of Labour", on 19 or 20 September

- 4th complementary day: La Fête de l'Opinion, "Celebration of Convictions", on 20 or 21 September

- 5th complementary day: La Fête des Récompenses, "Celebration of Honors (Awards)", on 21 or 22 September

- 6th complementary day: La Fête de la Révolution, "Celebration of the Revolution", on 22 or 23 September (on leap years only)

Converting from the Gregorian Calendar

Below are the Gregorian dates each Republican year (an in French) began while the calendar was in effect.

| An | Gregorian |

|---|---|

| I (1) | 22 September 1792 |

| II (2) | 22 September 1793 |

| III (3) | 22 September 1794 |

| IV (4) | 23 September 1795* |

| V (5) | 22 September 1796 |

| VI (6) | 22 September 1797 |

| VII (7) | 22 September 1798 |

| VIII (8) | 23 September 1799* |

| IX (9) | 23 September 1800 |

| X (10) | 23 September 1801 |

| XI (11) | 23 September 1802 |

| XII (12) | 24 September 1803* |

| XIII (13) | 23 September 1804 |

| XIV (14) | 23 September 1805 |

* Extra (sextile) day inserted before date, due to previous leap year[13]

The calendar was abolished in the year XIV (1805). After this date, opinions seem to differ on the method by which the leap years would have been determined if the calendar were still in force. There are at least four hypotheses used to convert dates from the Gregorian calendar:

- Equinox: The leap years would continue to vary in order to ensure that each year the autumnal equinox in Paris falls on 1 Vendémiaire, as was the case from year I to year XIV. This is the only method that was ever in legal effect, although it means that sometimes five years pass between leap years, such as the years 15 and 20.[14]

- Romme: Leap years would have fallen on each year divisible by four (thus in 20, 24, 28...), except most century years, according to Romme's proposed fixed rules. This would have simplified conversions between the Republican and Gregorian calendars since the Republican leap day would usually follow a few months after 29 February, at the end of each year divisible by four, so that the date of the Republican New Year remains the same (22 September) in the Gregorian calendar for the entire third century of the Republican Era (AD 1992–2091).[15]

- Continuous: The leap years would have continued in a fixed rule every four years from the last one (thus years 15, 19, 23, 27...) with the leap day added before, rather than after, each year divisible by four, except most century years. This rule has the advantage that it is both simple to calculate and is continuous with every year in which the calendar was in official use during the First Republic. Some concordances were printed in France, after the Republican Calendar was abandoned, using this rule to determine dates for long-term contracts.[16][17]

- 128-Year: Beginning with year 20, years divisible by four would be leap years, except for years divisible by 128. Note that this rule was first proposed by von Mädler, and not until the late 19th century. The date of the Republican New Year remains the same (23 September) in the Gregorian calendar every year from 129 to 256 (AD 1920–2047).[18][19][20]

The following table shows when several years of the Republican Era begin on the Gregorian calendar, according to each of the four above methods:

| An | AD/CE | Equinox | Romme | Continuous | 128-Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

XV (15) |

1806 |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XVI (16) |

1807 |

24 September* |

23 September |

24 September* |

24 September* |

|

XVII (17) |

1808 |

23 September |

23 September* |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XVIII (18) |

1809 |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XIX (19) |

1810 |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

23 September |

|

XX (20) |

1811 |

23 September |

23 September |

24 September* |

23 September |

|

CCXXVI (226) |

2017 |

22 September |

22 September |

22 September |

23 September |

|

CCXXVII (227) |

2018 |

23 September* |

22 September |

22 September |

23 September |

|

CCXXVIII (228) |

2019 |

23 September |

22 September |

23 September* |

23 September |

|

CCXXIX (229) |

2020 |

22 September |

22 September* |

22 September |

23 September* |

* Extra (sextile) day inserted before date, due to previous leap year

Current date and time

For this calendar, the Romme method of calculating leap years is used. Other methods may differ by one day. Time may be cached and therefore not accurate. Decimal time is according to Paris mean time, which is 9 minutes 21 seconds (6.49 decimal minutes) ahead of Greenwich Mean Time.

Criticism and shortcomings

Leap years in the calendar are a point of great dispute, due to the contradicting statements in the establishing decree[21] stating:

Each year begins at midnight, with the day on which the true autumnal equinox falls for the Paris Observatory.

and:

The four-year period, after which the addition of a day is usually necessary, is called the Franciade in memory of the revolution which, after four years of effort, led France to republican government. The fourth year of the Franciade is called Sextile.

These two specifications are incompatible, as leap years defined by the autumnal equinox in Paris do not recur on a regular four-year schedule. Thus, the years III, VII, and XI were observed as leap years, and the years XV and XX were also planned as such, even though they were five years apart.

A fixed arithmetic rule for determining leap years was proposed in the name of the Committee of Public Education by Gilbert Romme on 19 Floréal An III (8 May 1795). The proposed rule was to determine leap years by applying the rules of the Gregorian calendar to the years of the French Republic (years IV, VIII, XII, etc. were to be leap years) except that year 4000 (the last year of ten 400-year periods) should be a common year instead of a leap year. Shortly thereafter, he was sentenced to the guillotine, and his proposal was never adopted and the original astronomical rule continued, which excluded any other fixed arithmetic rule. The proposal was intended to avoid uncertain future leap years caused by the inaccurate astronomical knowledge of the 1790s (even today, this statement is still valid due to the uncertainty in ΔT). In particular, the committee noted that the autumnal equinox of year 144 was predicted to occur at 11:59:40 pm local apparent time in Paris, which was closer to midnight than its inherent 3 to 4 minute uncertainty.

The calendar was abolished by an act dated 22 Fructidor an XIII (9 September 1805) and signed by Napoleon, which referred to a report by Michel-Louis-Étienne Regnaud de Saint-Jean d'Angély and Jean Joseph Mounier, listing two fundamental flaws.

- The rule for leap years depended upon the uneven course of the sun, rather than fixed intervals, so that one must consult astronomers to determine when each year started, especially when the equinox happened close to midnight, as the exact moment could not be predicted with certainty.

- Both the era and the beginning of the year were chosen to commemorate an historical event which occurred on the first day of autumn in France, whereas the other European nations began the year near the beginning of winter or spring, thus being impediments to the calendar's adoption in Europe and America, and even a part of the French nation, where the Gregorian calendar continued to be used, as it was required for religious purposes.

The report also noted that the 10-day décade was unpopular and had already been suppressed three years earlier in favor of the 7-day week, removing what was considered by some as one of the calendar's main benefits.[22] The 10-day décade was unpopular with laborers because they received only one full day of rest out of ten, instead of one in seven, although they also got a half-day off on the fifth day. It also, by design, conflicted with Sunday religious observances.

Another criticism of the calendar was that despite the poetic names of its months, they are tied to the climate and agriculture of metropolitan France and therefore not applicable to France's overseas territories.[23]

Famous dates and other cultural references

The "18 Brumaire" or "Brumaire" was the coup d'état of Napoleon Bonaparte on 18 Brumaire An VIII (9 November 1799), which many historians consider as the end of the French Revolution. Karl Marx's 1852 essay The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon compares the 1851 coup of Louis Napoleon to his uncle's earlier coup.

Another famous revolutionary date is 9 Thermidor An II (27 July 1794), the date the Convention turned against Robespierre, who, along with others associated with the Mountain, was guillotined the following day. Based on this event, the term "Thermidorian" entered the Marxist vocabulary as referring to revolutionaries who destroy the revolution from the inside and turn against its true aims. For example, Leon Trotsky and his followers used this term about Joseph Stalin .

Émile Zola's novel Germinal takes its name from the calendar's month of Germinal.

The seafood dish lobster thermidor was probably named after the 1891 play Thermidor, set during the Revolution.[24][25]

The French frigates of the Floréal class all bear names of Republican months.

The Convention of 9 Brumaire An III, 30 October 1794, established the École Normale Supérieure. The date appears prominently on the entrance to the school.

The French composer Fromental Halévy was named after the feast day of 'Fromental' in the Revolutionary Calendar, which occurred on his birthday in year VIII (27 May 1799).

Neil Gaiman's The Sandman series included a story called "Thermidor" that takes place in that month during the French Revolution.[26]

The Liavek shared world series uses a calendar that is a direct translation of the French Republican calendar.

Sarah Monette's Doctrine of Labyrinths series borrows the Republican calendar for one of the two competing calendars (their usage splits between social classes) in the fictional city of Mélusine.

Jacques Rivette's 1974 film Celine and Julie Go Boating refers to the calendar and its hours of the day.

Alain Tanner's 1979 film Messidor presents a haphazard summer road trip of two young women in Switzerland.

See also

- Agricultural cycle

- Calendar reform

- Dechristianisation of France

- Decimal time

- Soviet calendar

- Solar Hijri calendar, astronomical equinox-based calendar used in Iran

- World Calendar

References

- ↑ Sylvain, Maréchal. "Almanach des Honnêtes-gens". Gallica. pp. 14–15. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k48116c.swf.f3.langFR.

- ↑ James Guillaume, Procès-verbaux du Comité d'instruction publique de la Convention nationale, t. I, pp. 227–228 et t. II, pp. 440–448 ; Michel Froechlé, " Le calendrier républicain correspondait-il à une nécessité scientifique ? ", Congrès national des sociétés savantes : scientifiques et sociétés, Paris, 1989, pp. 453–465.

- ↑ Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition. Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 19. ISBN 978-2-910015-09-1.

- ↑ "Concordat de 1801 Napoleon Bonaparte religion en france Concordat de 1801". Roi-president.com. 21 November 2007. Archived from the original on 10 September 2012. https://archive.is/20120910112012/http://www.roi-president.com/bio/bio-fait-Concordat%20de%201801.html. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition. Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 26. ISBN 978-2-910015-09-1.

- ↑ Le calendrier républicain: de sa création à sa disparition. Bureau des longitudes. 1994. p. 36. ISBN 978-2-910015-09-1.

- ↑ Richard A. Carrigan, Jr. "Decimal Time". American Scientist, (May–June 1978), 66(3): 305–313.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Thomas Carlyle (1867). The French revolution: a history. Harper. https://books.google.com/?id=81sQAAAAYAAJ.

- ↑ Clavis Calendaria: Or, A Compendious Analysis of the Calendar; Illustrated with Ecclesiastica, Historical, and Classical Anecdotes, 1, Rogerson and Tuxford, 1812, p. 38, https://books.google.com/books?id=pKjhAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA38#v=onepage

- ↑ Antoine Augustin Renouard (1822). Manuel pour la concordance des calendriers républicain et grégorien (2 ed.). A. A. Renouard. https://books.google.com/?id=oUoMAAAAIAAJ. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ↑ Ed. Terwecoren (1870). Collection de Précis historiques. J. Vandereydt. p. 31. https://books.google.com/books?id=6nIXAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA31.

- ↑ Philippe-Joseph-Benjamin Buchez, Prosper Charles Roux (1837). Histoire parlementaire de la révolution française. Paulin. p. 415. https://books.google.com/books?id=WU4QAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA415.

- ↑ Parise, Frank (2002). The Book of Calendars. Gorgias Press. pp. 376. ISBN 978-1-931956-76-5.

- ↑ Sébastien Louis Rosaz (1810). Concordance de l'Annuaire de la République française avec le calendrier grégorien. https://books.google.com/books?id=Aec6AAAAcAAJ.

- ↑ "Brumaire – Calendrier Républicain". Prairial.free.fr. http://prairial.free.fr/calendrier/calendrier.php?lien=discoursromme. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Antoine Augustin Renouard (1822). Manuel pour la concordance des calendriers républicain et grégorien: ou, Recueil complet de tous les annuaires depuis la première année républicaine (2 ed.). A. A. Renouard. https://books.google.com/?id=oUoMAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "Brumaire – Calendrier Républicain". Prairial.free.fr. http://prairial.free.fr/calendrier/calendrier.php?lien=manuel-eng. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ The French Revolution Calendar

- ↑ "Calendars". Projectpluto.com. http://www.projectpluto.com/calendar.htm#republican. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "The French Revolutionary Calendar, Calendars". Webexhibits.org. http://webexhibits.org/calendars/calendar-french.html. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ "Le Calendrier Republicain". Gefrance.com. http://www.gefrance.com/calrep/decrets.htm. Retrieved 30 January 2009.

- ↑ Antoine Augustin Renouard (1822). Manuel pour la concordance des calendriers républicain et grégorien: ou, Recueil complet de tous les annuaires depuis la première année républicaine (2 ed.). A. A. Renouard. p. 217. https://books.google.com/books?id=oUoMAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Canes, Kermit (2012). The Esoteric Codex: Obsolete Calendars. LULU Press. ISBN 1-365-06556-1.

- ↑ James, Kenneth (15 November 2006). Escoffier: The King of Chefs. Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 44. ISBN 978-1-85285-526-0. https://books.google.com/?id=JFIDd639wlQC&pg=PA44. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ "Lobster thermidor". Online Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lobster%20thermidor. Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- ↑ Gaiman, Neil (w), Woch, Stan (p), Giordano, Nick (i), Vozzo, Daniel (col), Klein, Todd (let), Berger, Karen (ed). "Thermidor" The Sandman v29, (August 1991), Vertigo Comics

Further reading

- Ozouf, Mona, 'Revolutionary Calendar' in Furet, François and Mona Ozouf, eds., Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution (1989)

- Shaw, Matthew, Time and the French Revolution: a history of the French Republican Calendar, 1789-Year XIV (2011)

External links

- Antique Decimal Watches

- Date converter for numerous calendars, including this one

- Dials & Symbols of the French revolution. The Republican Calendar and Decimal time.

- Republican calendar page, with an alternative Dashboard's widget

- The Republican Calendar and Decimal time online

- Brumaire – The Republican Calendar, with Windows and Mac OS X applications, including a Dashboard's widget. (fr es en eo pt de nl)

- Républican calendars (in French)