Engineering:Victorious Youth

| The Victorious Youth | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Lysippos? |

| Completion date | 4th/5th Century BCE |

| Medium | Bronze Sculpture |

| Subject | Hellenistic artwork |

| Location | J. Paul Getty Museum |

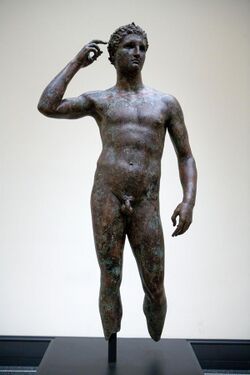

The Victorious Youth, Getty Bronze, also known as Atleta di Fano, or Lisippo di Fano is a Greek bronze sculpture, made between 300 and 100 BC,[1] in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Pacific Palisades, California. Many underwater bronzes have been discovered along the Aegean and Mediterrean coast; in 1900 sponge divers found the Antikythera Youth and the portrait head of a Stoic, at Antikythera, the standing Poseidon of Cape Artemision in 1926, the Croatian Apoxyomenos in 1996 and various bronzes until 1999. The Victorious Youth was found in the summer of 1964 in the sea off Fano on the Adriatic coast of Italy, snagged in the nets of an Italian fishing trawler. In the summer of 1977, The J. Paul Getty Museum purchased the bronze statue and it remains in the Getty Villa in Malibu, California. Bernard Ashmole, an archaeologist and art historian, was asked to inspect the sculpture by a Munich art dealer Heinz Herzer; he and other scholars attributed it to Lysippos, a prolific sculptor of Classical Greek art. The research and conservation of the Victorious Youth dates from the 1980s to the 1990s, and is based on studies in classical bronzes, and ancient Mediterranean specialists collaboration with the Getty Museum. The entire sculpture was cast in one piece; this casting technique is called the “lost wax” method; the sculpture was first created in clay with support to allow hot air to melt the wax creating a mold for molten bronze to be poured into, making a large bronze Victorious Youth. More recently, scholars have been more concerned with the original social context, such as where the sculpture was made, for what context and who he might be. Multiple interpretations of where the Youth was made and who the Youth is, are expressed in scholarly books by Jiri Frel, Paul Getty Museum curator, from 1973 to 1986, and Carol Mattusch, Professor of Art History at George Mason University specializing in Greek and Roman art with a focus in classical bronzes.

Description

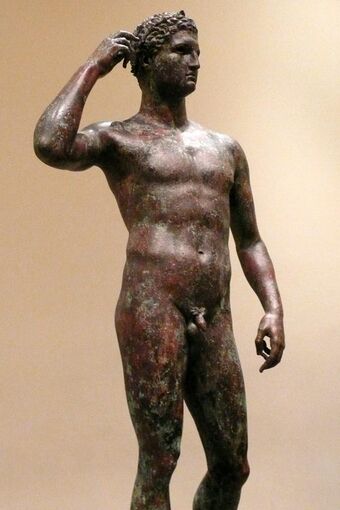

The sculpture may have been part of the crowd of sculptures of victorious athletes at Panhellenic Greek sanctuaries like Delphi and Olympia.[2] Other research has developed an argument that the Bronze represents a victorious athlete and a young prince whose lineage relates to Alexander the Great.[3] Therefore, this Olympic statue might have been dedicated anywhere within the ancient Greek world rather than Delphi or Olympia.[3] A possible reconstruction to the Getty Bronze is that the statue could have held a palm frond as these were gifts given to the victors. His right hand reaches to touch the winner's olive wreath on his head. The powerful head has led the Getty Bronze conservators to see it as a portrait; from the X-radiographs it has been concluded that the head was cast separately. With this technique the artist is able to focus on the head as an individual project to the full composition of the lithe body. The athlete's eyes were once inlaid, probably with bone, and his nipples are in contrasting copper. When examining the Bronze one must ask questions to understand its subject matter further, the wreath gives clues but what about the statue's build, this individual is a slender young man with a confident gaze. However, nothing about him refers to strength; his body is not particularly muscular or powerful in his stance.[4]

Techniques

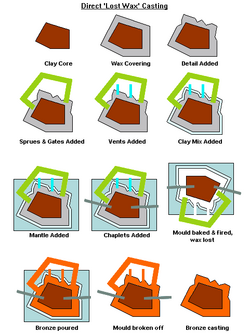

The Lost-Wax Process

Like many other Greek artworks, the bronze statue was made through the lost-wax method. Initially, the artist created an armature or support made with a thick wooden stick, iron bars or wires, and ancient reed sticks to support appendages from the torso. Surrounding the armature was a mixture of loam, sand, pebbles, pistachio nuts, fragments of clay and ivory, and glue. This combination kept the structure stable through multiple layers of application. After the final layer of clay was applied, wax sheets covered the statue's surface. During this process wax plates supported the figure from multiple points holding the statue vertically. Nails pierced into the wax to the inner core and protruded outwards to keep the statue positioned with the external mold. Slow heating allowed the wax to melt and fired the center and mold into a stable position. As the wax melted, an air space formed, creating a mold of the Victorious Youth, which became filled with molten bronze. The entire sculpture was cast in one piece; this casting technique is called the “lost wax” method.[5]

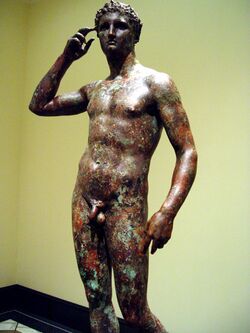

Polychromy

Evidence of polychrome survives; the nipples and lips are copper. This color choice may have interacted with the golden yellow of the bronze surface. There is a possibility of silver on the olive crown and more color to enhance the cheeks.[6] The inserted eyes would have given the bronze statue a naturalistic look. During the casting process of the Youth, these eye sockets would have been left empty and after the casting process both eyes would be inserted. The iris and pupil would be made of stone or glass, the white parts of the eyes would be ivory, bone or glass. To hold the eye in place a reddish sheet of copper would have been cut to fit the eye socket and then be curled into lashes. In addition to the application of bone, copper, glass, ivory, the bronze would be painted pale and gleaming like flesh to its viewers of the ancient world.[7]

Attribution

In the late 1980s antiquity scholars, and Getty Museum curator, Frel, used radiocarbon dating and stylistic analysis to attribute Lysippos as the creator of the Youth. Using Polykleitos's statues as a comparison, scholars seen a change in Polykleitan Kanon; the proportions become more subtle and richer in detail. There was a shift from the squareness in the face and innovative applications of elongation in the details of face and body. Lysippos was praised for his ability to evoke the soul from his statues through fleeting expressions.[8] Establishing an exact artist for the work is challenging due to the lack of original Greek bronzes to use for comparison. Ancient literature gives testimony of the classical sculptors; however, the artist did not sign the statues. There is no physical evidence to support the conclusion that Lysippos was the sculptor, but Frel, Mattusch, and ancient literary source Pliny, theorizes that Lysippos or his student was the Youth's creator. In Pliny's Natural History, he includes information about Greek sculptors extracted from earlier texts that are lost to us. During the fourth century B.C., Lysippos produced a multitude of sculptures; he alone probably sculpted fifteen hundred statues. He came from a family of bronze workers who developed a new method of increasing production, and the statues of athletes were a specialty.[9]

Dating

4th/5th Century

In 1974, Jerry Podany, Antiquities Conservator at the Getty Museum, and Marie Svoboda, a post-graduate intern in Antiquities Conservation at the Museum, conducted radiocarbon dating from a piece of wood that came from the statue's core, establishing the bronze as an ancient piece of work.[10] Over one month, Stapp removed the core of the bronze to eliminate issues related to humidity. During the removal, thermoluminescence dating and carbon 14 methods of examination confirmed the dating of the Victorious Youth to pre-Roman time. The rectangular plate on the statue's back of neck functioned as support for the Bronze's vertical position, a technique shared by two other fourth-century bronzes; the Marathon Boy and the Antikythera Youth. The curved body raised hip, smooth, and youthful anatomy are characteristics of a universal style—the fifth century B.C. developed these frameworks as a canonical expression of classical values. This form of expression went on through two and a half millennia, making dating and attribution challenging to determine with confidence. Despite slightly different interpretations, a collective agreement states that production can be dated to between the late fourth century and middle of the third century B.C.[11]

Collectors in Antiquity

Many statues from Greek cities and sanctuaries moved into Roman possession by the second century B.C. Vast collections of the antique style flourished, various statuary were looted and repurposed for Roman decoration. Like many other bronzes, the Victorious Youth traveled across the ocean on its way to Italy for reinstallation, possibly in public areas or in private homes.[12]

Interpretation

According to Jiri Frel, the stance and proportion of the Getty Bronze are similar to Lysippos's portrait of Demetrios Poliorketes (336-283 B.C.).[13] The least controversial theory is that the strong calves emphasize his athletic abilities, making him an Olympic runner who held a victor's palm branch in his left arm.[14] Claims state there are actual traces of palm after studying the statue.[15] Interpreting the anatomy is important in identifying the statue, from the detail in the joints, delicate attention to the wrists and ends of fingers there is a youthful representation. Greek games functioned as a major aspect in Greek culture and art. During the second century A.D., athletic contests were consistent events in various cities throughout Greece. At Olympia, these games were categorized for men, youth and boys. The Panhellenic Games occurred at religious sanctuaries in honor of the gods; Delphi hosted Pythian games as gifts for Apollo and athletic events at Olympia for Zeus. These games included footraces, combat sports, pentathlon, horse racing, and chariot racing. Delphi involved singing and playing of instruments to these Panhellenic Games. The victors received wreaths of different leaves depending on the site location; laurel at Delphi, olive at Olympia, pine at Isthmia, and wild celery at Nemea.[13] By understanding the specific wreaths worn by the winners, one could hypothesize which temple the statue would have housed.

Jiri Frel in 1982 examines the statue associated with Alexander the Great, based on reviewing the whole figure the stance to features doesn't represent a well bred citizen but higher in class. The artist's ability to capture not only beauty but produce a work of art that emphasizes the classical structures of Greek art during the Hellenistic period suggests the Youth as a descendant of one of the royal families from Alexander.[16] However, this theory did not survive the criticism of other scholars. Not until the 1990s was the next attempt to identify the sculpture and the Getty Museum didn't approve the name. Now much debate and research is specific to anatomy, its date and authorship; but with the uncertainties of stylistic assessments its difficult to reach a consensus.

Discovery

Many underwater bronzes have been discovered along the Aegean and Mediterrean coast; in 1900 sponge divers found the Antikythera Youth and the portrait head of a Stoic, at Antikythera, the standing Poseidon of Cape Artemision in 1926, and various bronzes until 1999. The sculpture was found in the summer of 1964 in the sea off Fano on the Adriatic coast of Italy, snagged in the nets of an Italian fishing trawler, the Ferri Ferruccio.[n 1][17] Italian art dealers paid the fishermen $5,600 USD for it.[18] The Getty Museum bought it from German art dealer Herman Heinz Herzer for almost $4M USD in 1977.[18][n 2] The unearthing of classical Greek and Roman sculptures are discovered all around the Mediterranean Sea; both empires reached far to the Iberian Peninsula, areas on Africa's northern coast, Asia Minor, the Middle East, and modern-day Europe. In further analyzing the Getty Bronze before conservation, a thick layer of incrustation covers the statue suggesting its location predates medieval or late Venetian ships transporting the object as spoils of war or recycling it for scrap metal.[19]

The precise location of the shipwreck, which preserved this object from being melted down like all but a tiny fraction of Greek bronzes, has not been established; it seems most likely that a Roman ship carrying looted objects was on its way to Italy when it foundered. The statue has been roughly broken off its former base, breaking away at the ankles. The clay core inside might give further detail to where and when it was made.

Restoration

In 1972 Heinz Herzer and Volker Kinnius, Munich gallery owner, wrote a report on the conservation project of Rudolph Stapp.[20] Rudolph Stapp was the main conservationist working with the Victorious Youth, who was known for his specialty in ancient bronzes. Past efforts to remove encrustation from the Bronze left various scratches in the metal. The Victorious Youth took three months to clean. First, the statue went into an artificial humidity chamber, exposing bronze disease. The disease occurs when chlorides and salts in the bronze react with moisture producing discolored spots. If left untreated, the copper part of bronze can easily fall off, leaving a disfigured image. Specialists neutralize the active corrosion by submerging it in a heated solution of sodium sesquicarbonate. The Victorious Youth is placed in a vacuum with the solution to penetrate interior layers without washing anything out. This process repeats itself twice and is finalized with one last artificial humidity test to check if the bronze disease resurfaces. A humid environment under 35% is necessary to keep the statue from deteriorating.[21]

Provenance

The Bronze was originally owned in 1971, by the Artemis Consortium, an association of several international art dealers, and then stored with a Munich art dealer, Heinz Herzer.[22] The Getty Museum is involved in a controversy regarding proper title to some of the artwork in its collection. The Museum's previous curator of antiquities, Marion True, was indicted in Italy in 2005 along with Robert E. Hecht on criminal charges relating to trafficking in stolen antiquities. The primary evidence in the case came from the 1995 raid of a Geneva, Switzerland warehouse which had contained a fortune in stolen artifacts. Italian art dealer Giacomo Medici was eventually arrested in 1997; his operation was thought to be "one of the largest and most sophisticated antiquities networks in the world, responsible for illegally digging up and spiriting away thousands of top-drawer pieces and passing them on to the most elite end of the international art market".[23]

In a letter to the J. Paul Getty Trust on December 18, 2006, True stated that she is being made to "carry the burden" for practices that were known, approved, and condoned by the Getty's Board of Directors.[24] True is currently under investigation by Greek authorities over the acquisition of a 2,500-year-old funerary wreath.

On November 20, 2006, the Director of the museum, Michael Brand, announced that twenty-six disputed pieces were to be returned to Italy, but not the Victorious Youth, for which the judicial procedure was still pending at the time.

In an interview to the Italian national newspaper Corriere della Sera on December 20, 2006 the Italian Minister of Cultural Heritage declared that Italy would place the museum under a cultural embargo if all the 52 disputed pieces would not return home overseas. On August 1, 2007 an agreement was announced providing that the museum would return 40 pieces to Italy out of the 52 requested, among which the Venus of Morgantina, which was returned in 2010, but not the Victorious Youth, whose outcome will depend upon the results of the criminal proceedings pending in Italy. On the very same day the public prosecutor of Pesaro formally requested that the statue be confiscated as it was unlawfully exported out of Italy, giving rise to a dispute that came to the Constitutional Court.[25]

Gallery

See also

- Antikythera Ephebe

- Lysippos

- Fano

Notes

- ↑ Other well-known underwater bronze finds have been retrieved, generally from shipwreck sites, in the Aegean and Mediterranean: the Antikythera mechanism, the Antikythera Ephebe and the portrait head of a Stoic discovered by sponge-divers at Antikythera in 1900, the Mahdia shipwreck off the coast of Tunisia, 1907; the Marathon Boy off the coast of Marathon, 1925; the standing Poseidon of Cape Artemision found off Cape Artemision in northern Euboea, 1926; the horse and Rider found off Cape Artemision, 1928 and 1937; the Riace bronzes, found in 1972; the Dancing Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, near Brindisi, 1992; and the Apoxyomenos recovered from the sea off the Croatian island of Lošinj in 1999.

- ↑ Though the Greek sculpture is unlikely ever to have touched Italian soil before its modern recovery,[citation needed] Italian authorities have pressed for its return, as part of Italy's patrimony. In fact, the statue was found by an Italian fishing trawler in international water: the owner of the ship was Italian and the statue was under Italian legislation. But the Italian laws state that every archeological good in Italy belongs to the People and cannot be sold.

References

- ↑ Giuffrida, Angela (5 December 2018). "Getty museum must return 2,000-year-old statue, Italian court rules". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/dec/05/italy-rules-getty-museum-must-return-2000-year-old-victorious-youth-statue.

- ↑ Analysis of fibres from the core reveal that they are flax; Pausanias noted in the second century CE that the only flax being grown in Greece was to be found around Olympia.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Mattusch, Carol (1997) (in English). The Victorious Youth. Malibu, California: Library of Congress. pp. 80. ISBN 0-89236-039-9.

- ↑ C., Mattusch, Carol (1997). The victorious youth.. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 78. ISBN 978-0-89236-470-1. OCLC 1158427881. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1158427881.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997) (in English). The Victorious Youth. Malibu, California: Library of Congress. pp. 80. ISBN 0-89236-039-9.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997) (in English). The Victorious Youth. Malibu, California: Library of Congress. pp. 80. ISBN 0-89236-039-9.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 69.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 36.

- ↑ C., Mattusch, Carol (1997). The victorious youth.. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 78. ISBN 978-0-89236-470-1. OCLC 1158427881. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1158427881.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 21.

- ↑ C., Mattusch, Carol (1997). The victorious youth.. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 78. ISBN 978-0-89236-470-1. OCLC 1158427881. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1158427881.

- ↑ C., Mattusch, Carol (1997). The victorious youth.. J. Paul Getty Museum. pp. 78. ISBN 978-0-89236-470-1. OCLC 1158427881. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1158427881.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Mattusch, Carol (1997) (in English). The Victorious Youth. Malibu, California: Library of Congress. pp. 80. ISBN 0-89236-039-9.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 49.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 81.

- ↑ Frel, Jiri (1982). The Getty Bronze. pp. 22.

- ↑ "Archeologia in rete"

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Giuffrida, Angela (5 December 2018). "Getty museum must return 2,000-year-old statue, Italian court rules". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/dec/05/italy-rules-getty-museum-must-return-2000-year-old-victorious-youth-statue.

- ↑ C., Mattusch, Carol (1997). The victorious youth.. J. Paul Getty Museum. ISBN 978-0-89236-470-1. OCLC 1158427881. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1158427881.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997). The Victorious Youth. pp. 20.

- ↑ Mattusch, Carol (1997) (in English). The Victorious Youth. Malibu, California: Library of Congress. pp. 80. ISBN 0-89236-039-9.

- ↑ Glueck, Grace (November 22, 1977). "Getty Museum Bronze Sets Record". New York Times.

- ↑ Men's Vogue, Nov/Dec 2006, Vol. 2, No. 3, pg. 46.

- ↑ LATimes.com ~ "Getty lets her take fall, ex-curator says"

- ↑ (in Italian) Giampiero Buonomo, La richiesta di pubblicità dell’udienza sull’appartenenza dell’atleta di Fano Diritto penale e processo, 2015, n. 9, p. 1173.

General references

- Frel, Jiri, 1978. The Getty Bronze (Malibu: The J. Paul Getty Museum).

- Antonietta Viacava, L' atleta di Fano, edizioni L'Erma di Bretschneider, 1995, ISBN:88-7062-868-X.

- Mattusch, Carol C. 1997. The Victorious Youth (Getty Museum Studies on Art; Los Angeles: The J. Paul Getty Museum). Reviewed in Bryn Mawr Classical Review

External links

- (in Italian) www.lisippo.org - Website of the cultural organisation who want the statue back to Fano, Italy.

- (in Italian) www.patrimoniosos.it

- (in English) (Getty Museum) Victorious Youth

- (in English) NPR, "Italy, Getty Museum at Odds over Disputed Art" 20 December 2006.

- (in English) (Los Angeles Times), Jason Felch, "The Amazing Catch They Let Slip Away": 11 May 2006

- (in English) (Trafficking Culture Project), Neil Brodie, "The Fano Bronze"

Newspaper articles

- (in Italian) Il Getty non restituisce le opere. Rutelli: «Cultural embargoe», by Pierluigi Panza, Corriere della Sera, November 14, 2006

- (in Italian) Il Getty Museum non rende le opere richieste, Corriere della Sera, November 23, 2006

- (in Italian) Rutelli attacca il Getty. Dubbi su 250 opere, di Paolo Conti, Corriere della Sera, November 24, 2006

- (in Italian) Rutelli-Getty, secondo round - “Non esponete opere rubate”, La Stampa, November 24, 2006

- (in Italian) Il Getty pronto a restituire la «Venere» Ma non restituirà il Lisippo., Corriere della Sera, November 26, 2006

- (in French) "L'Italie joue le bras de fer avec le Getty Museum", di Richard Heuzé, Le Figaro, December 26, 2006

- (in Italian) "No Lisippo, no Bernini", La Stampa, July 11, 2007

[ ⚑ ] 43°23′32″N 14°33′26″E / 43.39222°N 14.55722°E