Engineering:Hit-to-kill

Hit-to-kill, or kinetic kill, is a term used primarily in the military aerospace field to describe weapons that deliver their destructive power by hitting the target at high velocity and do not contain an explosive warhead. It has been used primarily in the anti-ballistic missiles (ABM) and anti-satellite weapons (ASAT) area, but some modern anti-aircraft missiles are also hit-to-kill. Hit-to-kill systems are part of the wider class of kinetic projectiles, a class that has widespread use in the anti-tank field.

Basic concept

Kinetic energy is a function of mass and the velocity of an object.[1] For a hit-to-kill weapon in the aerospace field, both objects are moving and it is the relative velocity that is important.[lower-alpha 1] In the case of the interception of the reentry vehicle (RV) from an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) during the terminal phase of the approach, the RV will be travelling at approximately 15,000 miles per hour (24,000 km/h) while the interceptor will be on the order of 7,000 miles per hour (11,000 km/h). Because the interceptor may not be approaching head-on, a lower bound on the relative velocity on the order of 16,000 miles per hour (26,000 km/h) is assumed,[2] or converting to SI units, approximately 7150 meters per second.

At that speed, every kilogram of the interceptor will have an energy of:

[math]\displaystyle{ KE = \frac{1}{2} m {v^2} = \frac{1}{2} \times 1\,\mathrm{kg}\times \left(7150\,\mathrm{\frac{m}{s}}\right)^2 = 25,561,250\ \mathrm{J} \approx 26\ \mathrm{MJ} }[/math]

TNT has an explosive energy of about 4853 joules per gram,[3] or about 5 MJ per kilogram. That means the impact energy of the mass of the interceptor is over five times that of a detonating warhead of the same mass.[2]

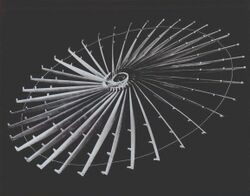

It may seem like this makes a warhead superfluous, but a hit-to-kill system has to actually hit the target, which may be on the order of half a meter wide, while a conventional warhead releases numerous small fragments that increase the possibility of impact over a much larger area, albeit with a much smaller impact mass. This has led to alternative concepts that attempt to spread out the potential impact zone without explosives.[2] The SPAD concept of the 1960s used a metal net with small steel balls that would be released from the interceptor missile,[4] while the Homing Overlay Experiment of the 1980s used a fan-like metal disk.[5]

As the accuracy and speed of modern surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) improved, and their targets began to include theatre ballistic missiles (TBMs), many existing systems have moved to hit-to-kill attacks as well. This includes the MIM-104 Patriot, whose PAC-3 version removed the warhead and upgraded the solid fuel rocket motor to produce an interceptor missile that is much smaller overall,[6] as well as the RIM-161 Standard Missile 3, which is dedicated to the anti-missile role.[7]

Advantages and disadvantages

The primary advantage to using the hit-to-kill principle is that it minimizes the launch mass of the weapon, as no weight has to be set aside for a separate warhead. Every part of the weapon, including the airframe, electronics and even the unburned maneuvering fuel contributes to the destruction of the target. Lowering the total mass of the vehicle offers advantages in terms of the required launch vehicle needed to reach the required performance, and also reduces the mass that needs to be accelerated during maneuvering.[2]

Another advantage of the concept is that any impact will almost certainly guarantee the destruction of the target. In contrast, a weapon using a blast fragmentation warhead will produce a large cloud of small fragments that will not cause as much destruction on impact. Both will produce effects that can easily be seen at long distance using radar or infrared detectors, but such a signal will generally indicate complete destruction in the case of hit-to-kill while the fragmentation case does not guarantee a "kill".[2]

The main disadvantage of the concept is that it requires extremely high accuracy in the guidance system, on the order of 0.5 metres (2 ft).[2]

See also

- Hellfire R9X

Explanatory notes

- ↑ As opposed to the anti-tank field, where the velocity of the tank can be approximated as zero compared to that of the weapon.

References

Citations

- ↑ Jain, Mahesh (2009). Textbook of Engineering Physics (Part I). p. 9. ISBN 978-81-203-3862-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=wKeDYbTuiPAC.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 GlobalSecurity.

- ↑ Cooper, Paul (1996). Explosives Engineering. Wiley-VCH. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-471-18636-6.

- ↑ Kalic, Sean (2012). US Presidents and the Militarization of Space, 1946–1967. Texas A&M University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9781603446914. https://books.google.com/books?id=BQNKDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA56.

- ↑ "Striking a Bullet with a Bullet: HOE". Lockheed Martin. https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/news/features/history/hoe.html.

- ↑ HeadOn.

- ↑ "RIM-161 SM-3 (AEGIS Ballistic Missile Defense)". GlobalSecurity.org. https://www.globalsecurity.org/space/systems/sm3.htm.

Bibliography

- "Missile Defense: Meeting the Challenge Head On". Lockheed Martin. https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/news/features/2015/mfc-missile-defense-meeting-the-challenge-head-on.html.

- "Kinetic Energy Hit-To-Kill Warhead". GlobalSecurity.org. https://www.globalsecurity.org/space/systems/kew-htk.htm.

External links