History:Salekhard–Igarka Railway

| Salekhard–Igarka Railway | |

|---|---|

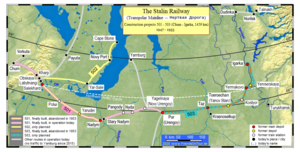

Map of the Stalin Railway | |

| Overview | |

| Status | in operation, projected, abandoned |

| Locale | Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous District, |

| History | |

| Opened | 1949 |

| Closed | 1953 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 1,459 km (907 mi) |

| Track gauge | 1,524 mm (5 ft) |

The 1,524 mm (5 ft) broad gauge Salekhard–Igarka Railway, (Трансполярная магистраль Transpolyarnaya Magistral, i.e. 'Transpolar Mainline') also referred to variously as Dead Road (Russian: Мёртвая дорога), and Stalinbahn, is an incomplete railway in northern Siberia. The railway was a project of the Soviet Gulag system that took place from 1947 until Joseph Stalin death in 1953. Construction was coordinated via two separate Gulag projects, the 501 Railway beginning on the River Ob and 503 Railway beginning on the River Yenisey, part of a grand design of Joseph Stalin to span a railway across northern Siberia to reach the Soviet Union's easternmost territories.[1][2]

The planned route from Igarka to Salekhard measured 1,297 kilometres (806 mi) in length. The project was built mostly with prisoner labour, particularly that of political prisoners,[3] and a large number perished.

A rebuilt section of the railway between Nadym and Novy Urengoy on the east bank of the Nadym River is still in operation, as is the extreme western section connecting Labytnangi and the railway to Vorkuta. The section from Salekhard to Nadym is planned to be rebuilt,[4] including a new bridge over the Ob to connect Salekhard to the rest of the Russian railway system via Labytnangi.[5] The section from Nadym to Pangody is also planned to be rebuilt.[6]

Purpose

The purpose of the railway was threefold: to facilitate the export of nickel from neighbouring Norilsk; to provide work for thousands of post-war prisoners; and to connect the deep-water seaports of Igarka and Salekhard with the western Russian railway network. With the Soviet industry relocated to western Siberia during World War II, it was seen as a strategic advantage to use the northward-flowing river systems to deliver supplies to Arctic Ocean ports. Salekhard, which was previously called Obdorsk, was on the Ob River, downstream from Novosibirsk and Omsk, and Igarka was on the Yenisei, which flowed north from Krasnoyarsk, Irkutsk, and the mountains around Lake Baikal. Connecting these two rivers was beneficial for transferring goods between cities and regions.

History

Prison labour was used to construct the railways of Imperial Russia and later those of the Soviet Union during the rapid industrialization of the 1930s.

Construction of the Salekhard–Igarka Railway began in the summer of 1949 under the supervision of Col. V.A. Barabanov. The 501st Labour Camp began work eastwards from Salekhard, while the 503rd Labour Camp pushed westwards from Igarka. Plans called for a single-track railway line with 28 stations and 106 sidings. It was not feasible to span the 2.3 km Ob River crossing or the 1.6 km wide Yenisei River crossing. Ferries were used in the summer, while in the winter, trains crossed the river using a track laid on the ice, using specially strengthened crossties.

A 1955 CIA paper detailed the construction method. After the course of the railway had been surveyed, a corduroy road was built over swampy ground. That was covered by layers of fascine, covered in turn by sand brought in by dump trucks. A 20-centimetre (7.9 in) layer of ballast was placed on the sand, and was topped by additional sand on which the crossties were emplaced. The line had many curves because of the need to avoid swamps.

It was estimated that anywhere from 80,000 to 120,000 labourers were engaged in the project. In the winter, construction was hampered by severe cold, permafrost, and food shortages. In the summer there were the problems of boggy terrain, diseases, and attacks by mosquitoes, gnats, midges, and horseflies. On the technical side, engineering problems included the difficulty of construction across permafrost, a poor logistical system, and tight deadlines, compounded by a severe lack of power machinery. As a result, railway embankments slowly settled into the marsh or were eroded by water pooling behind them. A shortage of materials also affected the project. One-metre segments of damaged rail lines from war-torn areas had to be sent in and welded to form 10-metre lengths.

As the project progressed, it became clear that there was little need for the railway. In 1952, officials permitted a reduced tempo of work. Construction was stopped in 1953 after Stalin's death. A total of 698 kilometres (434 mi) of railway were completed at an official cost of 260 million rubles, later estimated to be near 42 billion 1953 rubles (2.5% of total Soviet capital investment at the time, or about $10 billion in 1950 dollars). The project was quickly destroyed by frost heaves and structural failures arising from poor construction. At least 11 locomotives and 60,000 tons of metal were abandoned, and bridges gradually decayed or burned down. However, the corridor's telephone network remained in service until 1976.

About 350 km of track between Salekhard and Nadym remained in operation from the 1950s to the 1980s. However, in 1990, the line was shut down, and due to rising steel prices the first 92 km of rail from Salekhard were dismantled and recycled during the 1990s.

Current operations and future prospects

The far western section of the railway, linking Labytnangi with the railway to Vorkuta, and thus to the rest of the Russian rail network, is the only section that has continuously remained in operation. A bridge across the Ob to Salekhard is currently being built.

The section between Pangody and Novy Urengoy was rebuilt in the 1970s with the development of the gas deposits in the region, including a branch to Yamburg. The line connects to the rest of the Russian rail network at Korotchayevo.

Around the year 2000, discussion began about building a railway to Norilsk, about 220 km from Igarka, following much of the original corridor, to support the nickel and petroleum industry.

Known as part of the Northern Latitudinal Route, new construction of the railway section between Salekhard and Nadym allegedly started on 19 March 2010 in Salekhard.[1][7][8] This section was originally proposed to be finished in 2014 and opened in 2015,[4][9] with combined road-rail bridges across the Ob and Nadym rivers, thus connecting to the existing Russian railway system at both ends.[5]

As of 2016, the reconstruction of the Salekhard-Nadym line (in Template:Gauge gauge) was projected to take place between 2018-2022.[10]

As of April 2020, the Salekhard-Nadym line construction was ongoing, including a new bridge where the line crosses the Ob river. The process is expected to be complete in 2030.[11]

See also

- Northern Latitudinal Railway

- Rail transport in the Soviet Union

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gonzales, Daria (7 June 2012). "A living city among dead roads". RBTH. http://rbth.com/articles/2012/06/07/a_living_city_among_dead_roads_15830.html. Retrieved 9 July 2015.

- ↑ Lohse, Peggy (26 November 2014). "A journey to the northern edge of the world: to Igarka by the Yenisei river". RBTH. http://travel.rbth.com/travel/2014/26/11/polar_igarka_the_northern_edge_of_the_world.

- ↑ Gulag Memorial

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Industrial Urals – Polar Urals to build $1.9bn Salekhard – Nadym railroad". Marchmont. 10 Mar 2010. http://marchmontnews.com/Transport-Logistics/Volga/11938-Industrial-Urals-%E2%80%93-Polar-Urals-build-19bn-Salekhard-%E2%80%93-Nadym-railroad.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "On the "Ural Industrial – Ural Polar" Federal Comprehensive Project Implementation Process". Ural Industrial – Ural Polar. Feb 2010. http://www.cupp.ru/db/files/company_presentation.pdf.

- ↑ ""Газпром" подключился к проекту строительства Северного широтного хода". РБК. March 30, 2017. http://www.rbc.ru/business/30/03/2017/58dcd4c29a79470d2519d01a?from=newsfeed.

- ↑ "Governor of Tyumen oblast Vladimir Yakushev: "Our megaproject has huge investment potential" Governor's interview with the OJSC "Corporation Ural Industrial - Ural Polar"". cupp.ru. 10 March 2010. http://www.cupp.ru/press_release_18_eng_print.html.

- ↑ "Construction of the Salekhard - Nadym railroad has started!". Corporation Ural Industrial - Ural Polar. 19 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 March 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20130320132914/http://www.en.cupp.ru/press_2010_60.html. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ "salekhard past present and future". http://russiatrek.org/salekhard-city.

- ↑ "RZD signs concession agreement on Northern Latitudinal Railway". 21 October 2016. https://www.railwaypro.com/wp/rzd-signs-concession-agreement-on-northern-latitudinal-railway/.

- ↑ "Russia Explores Re-Development Of Its Trans-Polar Railway". Russia Briefing (Dezan Shira & Associates). April 21, 2020. https://www.russia-briefing.com/news/russia-explores-re-development-trans-polar-railway.html/. ""The section from Salekhard to Nadym is already under reconstruction, and includes a new bridge over the River Ob, which will connect Salekhard to the rest of the Russian railway system via Labytnangi. Development of these lines is expected to be completed by 2030.""

Books

- T. Paschkowa (author): Poljarnaja magistral, Moscow, Veče, 2007, ISBN:978-5-9533-1688-0 (The Polar Magistrale; Russian)

- Norbert Mausolf (author): Die Stalinbahn-Trilogie, Books on Demand GmbH, 2011, ISBN:978-3-8423-5398-5 (The Stalin Railway Trilogy; German)

External links

- The Dead Road

- 501-I Expedition AVP to Last Region of Russia (Russian)

- Salekhard history

- Photos of today's remains

- BBC article on Stalin's deadly railway to nowhere

- GULAG.cz Virtual tour through the Camp Barabanicha (Czech)

[ ⚑ ] 65°51′00″N 88°04′00″E / 65.85°N 88.0666667°E

|