Engineering:Lambert friction gearing disk drive transmission

The Lambert friction transmission (or friction disk drive or friction-drive transmission) was a mechanism devised and patented by John W. Lambert in 1904. It was a mechanical transmission that consisted of a friction wheel pressed against the back of the automobile motor flywheel main disk by a pedal controlled by the driver's foot. It was a type of clutch. When the pedal pressure was released the friction wheel could be moved across the power flywheel disk to provide a different ratio to give a driving speed as high or as low as desired; it even went into reverse to help decelerate while going forward or for driving backwards. The transmission was used in all of the vehicles manufactured by Lambert.

History and development

The invention was a transmission for automobiles that had no toothed gears and instead was a friction disk drive that transferred the motor power to the wheels for propulsion. John W. Lambert saw the need for simplicity, ease of upkeep, and low maintenance costs.[1] One of Lambert's greatest difficulties was the preconceived notion of the public that a transmission had to have gears to operate correctly.[2] The Lambert friction transmission (aka friction disk drive, friction-drive transmission) was a pivotal characteristic of the Union brand automobile and Lambert brand automobiles that were manufactured through the Buckeye Manufacturing Company.[3][4][5] Lambert is considered the father of the friction-drive transmission.[6]

Lambert first installed a gearless friction-drive transmission in an experimental 1898 gasoline driven horseless carriage automobile. He continued development with additional experimental automobiles in 1900 and 1901. He then produced the Union brand automobile with this type of transmission. He manufactured the Union automobile from 1902 through 1905 in Union City, Indiana.

The Lambert brand automobile developed from the Union automobile, and they were manufactured from 1905 through 1916 in Anderson.[6] It also had the gearless friction-drive transmission, which was used in all the vehicles that Lambert manufactured.[7] In addition to the various automobiles, this included Lambert trucks,[8] fire engine vehicles, and agricultural farm tractors.[9] All the Lambert brand vehicles were produced through 1916.[10] Their demise came about because of World War I and the conversion of the manufacturing facilities for making military items.[3] Lambert no longer made vehicles nor the friction transmission after the war.[10]

Toothless gearing

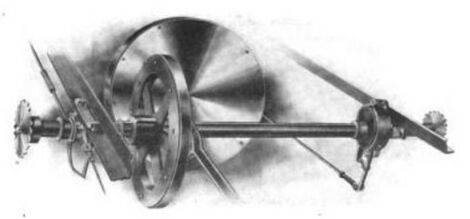

In Lambert's transmission, the master flywheel disk was a large disk connected directly to the automobile engine. A smaller disk known as the slave disk was placed at ninety degrees and the edge width of it rubbed up against the face of the flywheel disk to obtain energy. The master flywheel disk was 20 inches (510 mm) to 22 inches (560 mm) in width and was plated with an aluminum disk facing of equal diameter and circumference size with a thickness of some 5/16th of an inch. The slave wheel was 20 inches (510 mm) in breadth with a working face 1.75 inches (44 mm) wide on its outer edge. This wheel edge had a fibrous material on it for friction grab. It was designed to slip on a sleeve and was held on a steel shaft called a jackshaft.[11] [12]

The slave disk's rim of elastic paper or wood fiber wore for about 3000 miles of driving before it had to be replaced.[13] Lambert found that the combination of aluminum and fibrous material bearing surfaces gave the maximum degree of traction efficiency and had a good sturdiness over time for wear on the materials. Toothed gears on the other hand had to be in very close contact with each other at all times to be efficient and not slip. That caused the friction surfaces of the teeth to be exposed to great strains, and so the tooth transmission wore out quicker than the friction drive transmission.[14][15]

Speed regulation

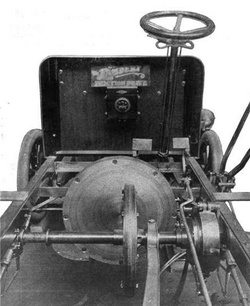

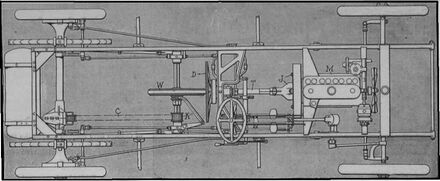

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the speed control mechanical layout. The speed adjustment was done by a lever L at the right side of the driver's seat. The lever had linkage going to a knuckle lever carrying a rod that had a U-shaped end sleeve controlling the slave disk W. This disk had a fibrous surface chiseled etched hub rim for friction grip. The knuckle lever controlled the slave disk travel back and forth across a car width shaft, which then set up the slave disk rim position placement where it would make contact with the flywheel aluminum disk D. The further out placement of the slave drive in relation to the face of the flywheel disk was a faster vehicle speed, while a placement closer to the center of the flywheel disk was a minimum speed. A placement just past center going the other way was then reverse for the vehicle.[16][17]

The friction transmission disk drive speed controller was a carry over feature from the manufacture of the Union brand automobile.[18] The motor power was distributed through a universal joint J and horizontal shaft T that was connected to aluminum disk D which slid forward and backward. It was operated by the driver's foot pedal and friction was applied by the pressure of the driver's foot on the pedal. This forced the aluminum disk D into the rim of the slave disk W and power was transferred onto the jackshaft. Through a sprocket chains were connected at the end of this shaft that went to the rear wheels and propelled the vehicle. When the driver no longer applied foot pressure a heavy duty spring automatically threw the aluminum disk back where it no longer was in contact with the slave disk and no power was on the vehicle's rear wheels.[16][17]

The slave disk glided in each direction freely with the U-shaped sleeve device when disengaged from the master flywheel disk, since it was then not under any friction pressure. This was done by the driver of the car manipulating the speed control lever next to the driver's seat. All speeds for the vehicle, from the fastest to the slowest, could be done in both directions, forward or backwards, depending on where the slave disk was placed on the motor flywheel disk.[19] The automobile could be assisted in decelerating by placing the slave disk in the reverse rotating direction when the vehicle was in forward motion.[17][20]

Automobile historian Ken Larson pointed out the Buckeye Manufacturing Company had an advertising slogan of The Car With a Thousand Speeds for the Lambert automobiles it produced during the early part of the 1900s in its plant at Anderson, Indiana. Larson claimed the wide speed range was made possible through use of their friction transmission that Lambert designed. He also declared that there was no clashing of gears, no jerking and no jarring in starting the automobile moving. He further explained that there were no gears to grind or strip and no clutch to slip when the transmission was engaged.[21]

Anderson Daily Bulletin newspaper in their "Man About Town" section said that in start up and all changes in speed were made so quietly and smoothly that the occupants of the car could not detect that the transmission had been engaged. The newspaper column went on to say that any number of speeds forward or backward could be produced through the operation of a driver controller lever that moved the friction wheel across the face of the motor fly wheel that provided the vehicle propulsion.[22]

Footnotes

- ↑ Forkner 2008, p. 383.

- ↑ "Lambert's work brings success". The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana): p. 6. 22 March 1914. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/93599870/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Naldrett 2016, p. 73.

- ↑ Historic American Engineering Report / Buckeye Manufacturing Company / HAER IN-35 (Report). National Park Service. 1968. p. 2. Historic American Engineering record. "...a form of transmission which used friction plates in place of gears."

- ↑ Loewenthal 1985, p. 4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "John W. Lambert". The Antique Automobile 24: 344–346. 1960. ISSN 0003-5831. OCLC 1481611.

- ↑ "Antique Truck 1912-ish Rare Unrestored Americana". TOPClassiccarsforsale.com. https://topclassiccarsforsale.com/other-makes/219661-antique-truck-1912-ish-lambert-rare-unrestored-americana-massachusetts-plate.html.

- ↑ "Lambert Auto Truck". The Indianapolis Star (Indianapolis, Indiana): p. 10. 20 May 1906. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/97030048/.

- ↑ "Auto Tractor for Orchards will be made in this City". Los Angeles Evening Post-Record (Los Angeles, California): p. 3. April 20, 1912. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/96898898/.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Scharchburg 1993, p. 25.

- ↑ "Each Model a Leader in Its Class". Cycle and Automobile Journal 13: 106–107. 1909. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Cycle_and_Automobile_Trade_Journal/xq0yAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22The+Lambert+Car+is+a+good+automobile+at+a+low+price%22+not+for+one+moment+to+be+confused+with+cheap+gear+driven+cars&pg=PA106&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ Dolnar 1906, p. 228.

- ↑ "The Lambert original friction drive". The San Francisco Call (San Francisco, California): p. 40. 23 July 1911. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/97104060/.

- ↑ "Patents / 261, 384 Friction Gearing". The Horseless Age 14: 48. 1904. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Horseless_Age/0x7mAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=but+will+always+present+a+smooth,+clean+surface+to+the+fiber+periphery&pg=PA48&printsec=frontcover.

- ↑ "Lambert's friction transmission explained". Car & Parts 18: 86. 1974.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "The Lambert Friction-Driven Cars". Motor Age 19: 54–55. 1911. OCLC 1776327. https://books.google.com/books?id=HP0GhwEuBp0C&dq=Lambert+friction+gearing+disk+drive+transmission+aluminum+flywheel+replace&pg=RA5-PA54. Retrieved 2022-07-04.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 "Changing Lambert name to Buckeye". Motor Age 22: 40–41. 1912. OCLC 1776328. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Motor_Age/dXdHAQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&bsq=Lambert%20friction%20transmission.

- ↑ Dolnar 1906, pp. 226-227.

- ↑ Trask, Charles A. (1918). "Friction Transmissions". The Journal of the Society of Automotive Engineers (Society of Automotive Engineers) 2 (6): 440–447.

- ↑ Dolnar 1906, pp. 228-229.

- ↑ Larson 2008, p. 195.

- ↑ "Lambert Auto Labeled 'Car With 1,000 Speeds'". Anderson Daily Bulletin (Anderson, Indiana): p. 4. 21 December 1967. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/97111053/.

Sources

- Dolnar, Hugh (1906). "The Lambert, 1906 Line of Automobiles". Cycle & Automobile Trade Journal 10 (7): 225–229. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Automobile_Trade_Journal/-jBLAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22The+Lambert,+1906+Line+of+Automobiles%22&pg=PA225&printsec=frontcover.

- Forkner, John La Rue (2008). History of Madison County, Indiana. Bridgeport National Bindery. OCLC 712176620.

- Larson, Len (2008). Dreams to Automobiles. McGraw Hill. ISBN 9781469101040.

- Loewenthal, Stuart H. (1985). Design of Traction Drives. NASA - Scientific and Technical Information Branch. OCLC 13590781.

- Naldrett, Alan (2016). Lost Car Companies of Detroit. Arcadia. ISBN 9781625856494. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Lost_Car_Companies_of_Detroit/xcQ4CwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=John+Lambert+friction+gearing+disk+drive+transmission&pg=PA72&printsec=frontcover.

- Scharchburg, Richard P. (1993). Carriages Without Horses. Society of Automotives Engineers. ISBN 1-56091-380-0.