Philosophy:Recognition-by-components theory

The recognition-by-components theory, or RBC theory,[1] is a process proposed by Irving Biederman in 1987 to explain object recognition. According to RBC theory, we are able to recognize objects by separating them into geons (the object's main component parts). Biederman suggested that geons are based on basic 3-dimensional shapes (cylinders, cones, etc.) that can be assembled in various arrangements to form a virtually unlimited number of objects.[2]

Geons

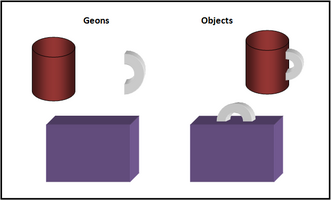

The recognition-by-components theory suggests that there are fewer than 36 geons which are combined to create the objects we see in day-to-day life.[3] For example, when looking at a mug we break it down into two components – "cylinder" and "handle". This also works for more complex objects, which in turn are made up of a larger number of geons. Perceived geons are then compared with objects in our stored memory to identify what it is we are looking at. The theory proposes that when we view objects we look for two important components.

- Edges – This enables us to maintain the same perception of the object regardless of viewing orientation.

- Concavities – The area where two edges meet. These enable us to observe the separation between two or more geons.

Analogy between speech and objects

In his proposal of RBC, Biederman makes an analogy to the composition of speech and objects that helps support his theory. The idea is that about 44 individual phonemes or "units of sound" are needed to make up every word in the English language, and only about 55 are needed to make up every word in all languages. Though small differences may exist between these phonemes, there is still a discrete number that make up all languages.

A similar system may be used to describe how objects are perceived. Biederman suggests that in the same way speech is made up by phonemes, objects are made up by geons, and as there are a great variance of phonemes, there is also a great variance of geons. It is more easily understood how 36 geons can compose the sum of all objects, when the sum of all language and human speech is made up of only 55 phonemes.

Viewpoint invariance

One of the most defining factors of the recognition-by-components theory is that it enables us to recognize objects regardless of viewing angle; this is known as viewpoint invariance. It is proposed that the reason for this effect is the invariant edge properties of geons.[4]

The invariant edge properties are as follows:

- Curvature (various points of a curve)

- Parallel lines (two or more points which follow the same direction)

- Co-termination (the point at which two points meet and therefore cease to continue)

- Symmetry and asymmetry

- Co-linearity (points branching from a common line)

Our knowledge of these properties means that when viewing an object or geon, we can perceive it from almost any angle. For example, when viewing a brick we will be able to see horizontal sets of parallel lines and vertical ones, and when considering where these points meet (co-termination) we are able to perceive the object.

Strengths of the theory

Using geons as structural primitives results in two key advantages. Because geons are based on object properties that are stable across viewpoint ("viewpoint invariant"), and all geons are discriminable from one another, a single geon description is sufficient to describe an object from all possible viewpoints. The second advantage is that considerable economy of representation is achieved: a relatively small set of geons form a simple "alphabet" that can combine to form complex objects. For example, with only 24 geons, there are 306 billion possible combinations of 3 geons, allowing for all possible objects to be recognized.

In addition, some research suggests that the ability to recognize geons and compound structures of geons may develop in the brain as early as four months old, making it one of the fundamental skills that infants use to perceive the world.[5]

Experimental evidence

- Participants show a remarkable ability to recognise objects despite visual noise provided that the geons are visible.

- Removal of feature-relation information (relations between geons) impairs object recognition.

- No visual priming if different geons are used between trials

Weaknesses

RBC theory is not in itself capable of starting with a photograph of a real object and producing a geons-and-relations description of the object; the theory does not attempt to provide a mechanism to reduce the complexities of real scenes to simple geon shapes. RBC theory is also incomplete in that geons and the relations between them will fail to distinguish many real objects. For example, a pear and an apple are easily distinguished by humans, but lack the corners and edges needed for RBC theory to recognize they are different. However, Irving Biederman has argued that RBC theory is the "preferred" mode of human object recognition, with a secondary process handling objects that are not distinguishable by their geons. He further states that this distinction explains research suggesting that objects may or may not be recognized equally well with changes in viewpoint.

References

- ↑ Sternberg, Robert J. (2006): Cognitive Psychology. 4th Ed. Thomson Wadsworth.

- ↑ Biederman, I. (1987) Recognition-by-components: a theory of human image understanding. Psychol Rev. 1987 Apr;94(2):115-147.

- ↑ Eyseneck, M W. Keane, M T, 2010. Cognitive Psychology: A Students Handbook. 6th Edition. Hove: Psychology Press

- ↑ Biederman, I. (2000). Recognizing depth-rotated objects: A review of recent research and theory. Spatial Vision, 13, 241–253.

- ↑ Haaf, R., Fulkerson, A., Jablonski, B., Hupp, J., Shull, S., Pescara-Kovach, L. (2003). Object recognition and attention to object components by preschool children and 4-month-old infants. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 86(2), 108-123.

|