Social:Phoenician papyrus letters

The Phoenician papyrus letters are the only two known papyrus letters written in Phoenician. The first was discovered in Cairo in 1939, and the second in Saqqara in 1940.[1] Both letters were first published by Noël Aimé-Giron.

Saqqara letter (KAI 50)

The Saqqara Phoenician letter is a papyrus letter written in the Phoenician language that was found in a mastaba well in Saqqara, Egypt, in 1940.[2][3] It is one of only two known papyrus letters written in Phoenician.[4]

The letter is written from a woman to another woman, both speaking Phoenician but living in Egypt. The letter reads as follows:

To Arishut daughter of Eshmunyaton: Tell my sister Arishuth, your sister Bisha said: Are you in good health? I, too, am in good health. I bless you to Baalsaphon and all the gods of Tahpanhas so that they may keep you always in good health. I have indeed received the silver that you have sent me; 320 shekels and a quarter... This was all the silver that belonged to me... And you have sent me the document of discharge that...

Cairo letter (KAI 51)

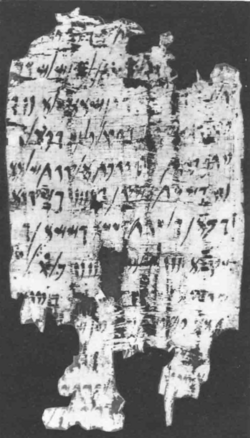

The Cairo papyrus was first published in 1939 by Noël Aimé-Giron, who found it in the archives of the Egyptian Museum at Cairo.[5] It is not known where the papyrus had been discovered originally. It measures only 20 by 11.5 cm. On the basis of letter shapes Aimé-Giron has dated the letter to about 300 BCE.[6]

Due to its unique character and damaged state, the text is difficult to interpret, but Aimé-Giron thinks it was an “envoi de fonds”,[7] a letter accompanying a money transfer. The "back" side of the letter contains the list of adressees, the front side consists of a list of various groups of items. At the end of each of those groups a number is added, apparently the money value associated with that group. Halfway the list a total (or subtotal) is also given (lines A.8-9). If a subtotal, the following lines may specify expenses (note the "signet-rings" in lines A.9-11), to be subtracted from the subtotal to arrive at the net sum in the money bag.

Because it seems that sacrifices are mentioned several times in the list (A.2,3,5), Aimé-Giron thinks that the sender of the letter might be a religious institution where the priests acquired an income from various items, both agricultural produce that they sold and sacrificial services that they performed.

Front side of the letter

Before "line 1" one or two lines may be missing. The remaining text reads (underlined characters are uncertain):[5][8][9]

(line A.1-2) [...........]TY WBRB ŠL[MM?] / [.....]M[..]ḤTN L[.]N ŠLŠ I ... for the sacrifices(??) / ... three(?): 1; (2-3) W/QLLM W[....] WBNŠMM ‘LM II and pitchers (vessels) and ... and Benšamim holocausts(??): 2; (3-4) W/BṢL R’ŠY[..] WBṢL PLN‘ WP’L and onions of Raš-Y[...](?), and onions of PLN‘, and beans(??) (5-6) ḤRN K’RT [..] BRKTMLQRT ŠLMM / III ... Biriktmelqart, sacrifices: 3; (6) WZYT MŠQN (=MŠQL?) XXIIIII and olives weighing(??) 25 (x?); (6-8) WŠQDM / WKMN WL‘RTY ‘‘M WŠŠMN W/‘QLM III and almonds, and cumin, and ..., and sesame, and ‘QLM: 3; (8) WL[...] IIIII and ...: 5; (8-9) KL’ L/YRḤM[.]‘ [.......] the total thereof for [recent] months: ...; (9-10) WḤ[T]M WḤ/TMM BṬB‘T and a signet-ring and stamped signet-rings (coins??), (10-11) W[..] WḤN Š[......] / [....]‘‘ [..Ḥ]TM ’R[.....] and ... / ... signet-ring ... (12) [...]M ḤṢ [....] WLBKWRY [....] ... and for the first-fruits of ... (13) [.....]L[.... BK]WRY YN[...] [... fir]st-fruits of YN(...)

Back side of the letter

This side of the letter was written by another, but contemporaneous hand:[5][8][9]

(line B.1) [MN] ‘BDMLKT — LBDB‘L LRB [From] ‘Abdmilkat, — to Bodba‘al, the governor! (2) [‘L PN (...) B]DB‘L RB ḤRMN YM W‘L PN ’Š Š LḤR[MN YM (...)] [For Bo]dba‘al, governor of ḤRMN-on-the-Sea, and for the people of ḤRMN-on-the-Sea, (3) [(...) W‘L ]PN ’LD’DNDNḤ W’B’Y WNKB WR’ŠL[...] [... and] for Eldōdnādinaḫ and ’B’Y and NKB and R’ŠL(...) (4) KSP[.....]R[.....]BN LKN LKL ‘M ŠMŠ[...] money ... so that it shall be for all the people of Šmš(...) (5) WKMR[ (...)] and ...

In line B.1 a wide blank space was intentionally left free between the names of the sender and the adressee (here rendered by the ‘—’ sign). The string closing the accompanying money bag was made to pierce this blank space, then knotted, after which the knot was sealed, thus guaranteeing the receiver of the money transport that the money had not been tampered with.[10]

See also

- Textbook of Aramaic Documents from Ancient Egypt

References

- ↑ Vance, Donald R. “Literary Sources for the History of Palestine and Syria: The Phœnician Inscriptions,.” The Biblical Archaeologist 57, no. 1 (1994): 2–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/3210392. "... There are two private letters on papyri (KAI ## 50-51)..."

- ↑ Noël Aimé-Giron, 1940, Ba'al Saphon et les dieux de Tahpanhès dans un nouveau papyrus phénicien, ASAÉ 40 433-60, Pl. xl

- ↑ Delekat, L. “Ein Papyrusbrief in Einer Phönizisch Gefärbten Konsekutivtempus-Sprache Aus Ägypten (KAI 50).” Orientalia 40, no. 4 (1971): 401–9. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43078963.

- ↑ Greenfield, Jonas C. “Notes on the Phoenician Letter from Saqqara.” Orientalia 53, no. 2 (1984): 242–44. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43075264. "It remains the sole example of a letter in Phoenician to have been discovered so far."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Noël Aimé-Giron, 1939, Adversaria semitica: 1. Papyrus Phénicien, Bulletin de l’Institute Francais d’Archaologie Orientale 38 (1939), p. 1-63

- ↑ Aimé-Giron (1939), p. 16.

- ↑ Aimé-Giron (1939), p. 15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Donner, Herbert; Rölig, Wolfgang (2002). Kanaanäische und aramäische Inschriften (5 ed.). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. I, 14.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Krahmalkov, Charles R. (2000). Phoenician-Punic Dictionary. Leuven: Peeters / Departement Oosterse Studies. ISBN 90-429-0770-3.

- ↑ Aimé-Giron (1939), p. 2.

|