Social:Cristero War

| Cristero War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Map of Mexico showing regions in which Cristero outbreaks occurred Large-scale outbreaks Moderate outbreaks Sporadic outbreaks | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Support: Ku Klux Klan |

Knights of Columbus | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Plutarco Elías Calles Emilio Portes Gil Joaquín Amaro Domínguez Saturnino Cedillo Heliodoro Charis Marcelino García Barragán Jaime Carrillo Genovevo Rivas Guillén Álvaro Obregón † |

Enrique Gorostieta Velarde † José Reyes Vega † Alberto B. Gutiérrez Aristeo Pedroza Andrés Salazar Carlos Carranza Bouquet † Dionisio Eduardo Ochoa † Barraza Damaso Domingo Anaya † Jesús Degollado Guízar Luis Navarro Origel † Lauro Rocha Lucas Cuevas † Matías Villa Michel Miguel Márquez Anguiano Manuel Michel Victoriano Ramírez † Victorino Bárcenas † | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

|

Estimated 250,000 dead 250,000 fled to the United States (mostly non-combatants) | |||||||

thumb|Government forces publicly hanged Cristeros on main thoroughfares throughout Mexico, including in the Pacific states of [[Colima and Jalisco, where bodies often remained hanging for extended lengths of time.]]

The Cristero War, also known as the Cristero Rebellion or La Cristiada [la kɾisˈtjaða], was a widespread struggle in central and western Mexico in response to the imposition of secularist and anticlerical articles of the 1917 Constitution of Mexico, which were perceived by opponents as anti-Catholic measures aimed at imposing state atheism. The rebellion was instigated as a response to an executive decree by Mexican President Plutarco Elías Calles to enforce Articles 3, 5, 24, 27, and 130 of the Constitution, a move known as the Calles Law. Calles sought to eliminate the power of the Catholic Church and all organizations which were affiliated with it and to suppress popular religious celebrations in local communities.

The massive popular rural uprising in north-central Mexico was tacitly supported by the Church hierarchy, and it was also aided by urban Catholic supporters. US Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow brokered negotiations between the Calles government and the Church. The government made some concessions, the Church withdrew its support for the Cristero fighters, and the conflict ended in 1929. The rebellion has been variously interpreted as a major event in the struggle between church and state that dates back to the 19th century with the War of Reform, as the last major peasant uprising in Mexico after the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, and as a counter-revolutionary uprising by prosperous peasants and urban elites against the revolution's agrarian and rural reforms.

Background

Conflict between church and state

The Mexican Revolution remains the largest conflict in Mexican history. The overthrow of the dictator Porfirio Díaz unleashed disorder, with many contending factions and regions. The Catholic Church and the Díaz government had come to an informal modus vivendi in which the state formally maintained the anticlerical articles of the liberal Constitution of 1857 but failed to enforce them. Having a change of leadership or a wholesale overturning of the previous order was a potential danger to the Church's position. In the democratizing wave of political activity, the National Catholic Party (Partido Católico Nacional) was formed. President Francisco Madero was overthrown and assassinated in a February 1913 military coup led by General Victoriano Huerta, who brought back supporters of the Porfirian order. After the ouster of Huerta in 1914, the Catholic Church was the target of revolutionary violence and fierce anticlericalism by many northern revolutionaries. The Constitutionalist faction won the revolution and its leader, Venustiano Carranza, had a new revolutionary constitution drawn up, the Constitution of 1917. It strengthened the anticlericalism of the previous document, but President Carranza and his successor, General Alvaro Obregón, were preoccupied by their internal enemies and were lenient in enforcing the Constitution's anticlerical articles, especially in areas in which the Church was powerful.

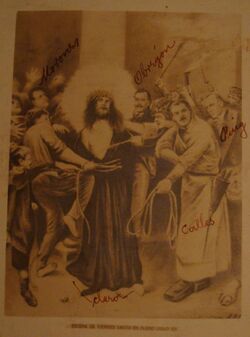

The Calles administration felt that the Church was challenging its revolutionary initiatives and legal basis. To destroy the Church's influence over the Mexicans, anticlerical laws were instituted, which started a ten-year religious conflict that resulted in the death of thousands of armed civilians against an armed professional military that was sponsored by the government. Calles has been characterized by some as leading an atheist state[1] and his program as being one to eradicate religion in Mexico.[2]

Crisis

A period of peaceful resistance to the enforcement of the anticlerical provisions of the Constitution by Mexican Catholics unfortunately brought no result. Skirmishing broke out in 1926, and violent uprisings began in 1927.[3] The government called the rebels Cristeros since they invoked the name of Jesus Christ under the title of "Cristo Rey" or Christ the King, and the rebels soon used the name themselves. The rebellion is known for the Feminine Brigades of St. Joan of Arc, a brigade of women who assisted the rebels in smuggling guns and ammunition, and for certain priests who were tortured and murdered in public and later canonized by Pope John Paul II. The rebellion eventually ended by diplomatic means brokered by US Ambassador Dwight W. Morrow, with financial relief and logistical assistance provided by the Knights of Columbus.[4]

The rebellion attracted the attention of Pope Pius XI, who issued a series of papal encyclicals from 1925 to 1937. On November 18, 1926, he issued Iniquis afflictisque ("On the Persecution of the Church in Mexico") to denounce the violent anticlerical persecution in Mexico.[5] Despite the government's promises, the persecution of the Church continued. In response, Pius issued Acerba animi on September 29, 1932.[5][6] As the persecution continued, he issued a letter to the bishops of Mexico, Firmissimam constantiam,[7] and expressed his opposition and granted papal support for Catholic Action in Mexico for the third consecutive time with the use of plenary indulgence on March 28, 1937.[8]

1917 Mexican Constitution

The 1917 Constitution was drafted by the Constituent Congress convoked by Venustiano Carranza in September 1916, and it was approved on February 5, 1917. The new constitution was based in the 1857 Constitution, which had been instituted by Benito Juárez. Articles 3, 27, and 130 of the 1917 Constitution contained secularizing sections that heavily restricted the power and the influence of the Catholic Church.

The first two sections of Article 3 stated: "I. According to the religious liberties established under article 24, educational services shall be secular and, therefore, free of any religious orientation. II. The educational services shall be based on scientific progress and shall fight against ignorance, ignorance's effects, servitudes, fanaticism and prejudice."[9] The second section of Article 27 stated: "All religious associations organized according to article 130 and its derived legislation, shall be authorized to acquire, possess or manage just the necessary assets to achieve their objectives."[9]

The first paragraph of Article 130[10] stated: "The rules established at this article are guided by the historical principle according to which the State and the churches are separated entities from each other. Churches and religious congregations shall be organized under the law."

The Constitution also provided for obligatory state registration of all churches and religious congregations and placed a series of restrictions on priests and ministers of all religions, who were not allowed to hold public office, canvas on behalf of political parties or candidates, or inherit from persons other than close blood relatives.[9] It also allowed the state to regulate the number of priests in each region and even to reduce the number to zero, and it forbade the wearing of religious garb and excluded offenders from a trial by jury. Carranza declared himself opposed to the final draft of Articles 3, 5, 24, 27, 123 and 130, but the Constitutional Congress contained only 85 conservatives and centrists who were close to Carranza's rather restrictive brand of "liberalism." Against them were 132 delegates who were more radical.[11][12][13]

Article 24 stated: "Every man shall be free to choose and profess any religious belief as long as it is lawful and it cannot be punished under criminal law. The Congress shall not be authorized to enact laws either establishing or prohibiting a particular religion. Religious ceremonies of public nature shall be ordinarily performed at the temples. Those performed outdoors shall be regulated under the law."[9]

Background

Violence on a limited scale occurred throughout the early 1920s, but it never rose to the level of widespread conflict. In 1926, the passage of stringent anticlerical criminal laws and their enforcement by the so-called Calles Law, together with peasant revolts against land reform in the heavily-Catholic Bajio and the clampdown on popular religious celebrations such as fiestas, caused scattered guerrilla operations to coalesce into a serious armed revolt against the government.

Both Catholic and anticlerical groups turned to terrorism. Of the several uprisings against the Mexican government in the 1920s, the Cristero War was the most devastating and had the most long-term effects. The diplomatic settlement of 1929 brokered by the US Ambassador Morrow between the Catholic Church and the Mexican government was supported by the Vatican. Although many Cristeros continued fighting, the Church no longer gave them tacit support. The persecution of Catholics and anti-government terrorist attacks continued into the 1940s, when the remaining organized Cristero groups were incorporated into the Sinarquista Party.[14][15][16][17]

The Mexican Revolution started in 1910 against the long autocracy of Porfirio Díaz and for the masses' demand of land for the peasantry. However, Calles took stances that were radically anti-Catholic, despite the Church's overwhelming support from the people.[18] Francisco I. Madero was the first revolutionary leader. He was elected president in November 1911 but was overthrown and executed in 1913 by the counterrevolutionary General Victoriano Huerta. After Huerta seized power, Archbishop Leopoldo Ruiz y Flóres from Morelia published a letter condemning the coup and distancing the Church from Huerta. The newspaper of the National Catholic Party, representing the views of the bishops, severely attacked Huerta and so the new regime jailed the party's president and halted the publication of the newspaper. Nevertheless, some members of the party decided to participate in Huerta's regime, such as Eduardo Tamariz.[19][20] The revolutionary generals Venustiano Carranza, Francisco Villa and Emiliano Zapata, who won against Huerta's federal army under the Plan of Guadalupe, had friends among Catholics and the local parish priests who aided them[21][22] but also blamed high-ranking Catholic clergy for supporting Huerta.[23][24][25]

Carranza was the first president under the 1917 Constitution but he was overthrown by his former ally Álvaro Obregón in 1919. Obregón took over the presidency in late 1920 and effectively applied the Constitution's anticlerical laws only in areas in which the Church was the weakest. The uneasy truce with the Church ended with Obregón's 1924 handpicked succession of the atheist Plutarco Elías Calles.[26][27] Mexican Jacobins, supported by Calles's central government, went beyond mere anticlericalism and engaged in secular antireligious campaigns to eradicate what they called "superstition" and "fanaticism," which included the desecration of religious objects as well as the persecution and the murder of members of the clergy.[18]

Calles applied the anticlerical laws stringently throughout the country and added his own anticlerical legislation. In June 1926, he signed the "Law for Reforming the Penal Code," which was unofficially called the "Calles Law." It provided specific penalties for priests and individuals who violated the provisions of the 1917 Constitution. For instance, wearing clerical garb in public, outside church buildings, earned a fine of 500 pesos (then the equivalent of US$250), and a priest who criticized the government could be imprisoned for five years.[28] Some states enacted oppressive measures. Chihuahua enacted a law permitting only one priest to serve all Catholics in the state.[29] To help enforce the law, Calles seized church property, expelled all foreign priests and closed the monasteries, convents and religious schools.[30]

Rebellion

Peaceful resistance

In response to the measures, Catholic organizations began to intensify their resistance. The most important group was the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty, founded in 1924, which was joined by the Mexican Association of Catholic Youth, founded in 1913, and the Popular Union, a Catholic political party founded in 1925.

In 1926, Calles intensified tensions against the clergy by ordering all local churches in and around Jalisco to be bolted shut. The places of worship remained shut for two years. On July 14, Catholic bishops endorsed plans for an economic boycott against the government, which was particularly effective in west-central Mexico (the states of Jalisco, Michoacan, Guanajuato, Aguascalientes, and Zacatecas). Catholics in those areas stopped attending movies and plays and using public transportation, and Catholic teachers stopped teaching in secular schools.[citation needed]

The bishops worked to have the offending articles of the Constitution amended. Pope Pius XI explicitly approved the plan. The Calles government considered the bishops' activism to be sedition and had many more churches closed. In September 1926, the episcopate submitted a proposal to amend the Constitution, but the Mexican Congress rejected it on September 22.[citation needed]

Escalation of violence

On August 3, in Guadalajara, Jalisco, some 400 armed Catholics shut themselves in the Church of Our Lady of Guadalupe ("Santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe"). They exchanged gunfire with federal troops and surrendered when they ran out of ammunition. According to US consular sources, the battle resulted in 18 dead and 40 wounded. The following day, in Sahuayo, Michoacán, 240 government soldiers stormed the parish church. The priest and his vicar were killed in the ensuing violence.

On August 14, government agents staged a purge of the Chalchihuites, Zacatecas, chapter of the Association of Catholic Youth and executed its spiritual adviser, Father Luis Bátiz Sainz. The execution caused a band of ranchers, led by Pedro Quintanar, to seize the local treasury and to declare themselves in rebellion. At the height of the rebellion, they held a region including the entire northern part of Jalisco. Luis Navarro Origel, the mayor of Pénjamo, Guanajuato, led another uprising on September 28. His men were defeated by federal troops in the open land around the town but retreated into the mountains, where they continued guerrilla warfare. In support of the two guerrilla Apache clans, the Chavez and Trujillos helped smuggle arms, munitions and supplies from the US state of New Mexico.

That was followed by a September 29 uprising in Durango, led by Trinidad Mora, and an October 4 rebellion in southern Guanajuato, led by former General Rodolfo Gallegos. Both rebel leaders adopted guerrilla tactics since their forces were no match for federal troops. Meanwhile, rebels in Jalisco, particularly the region northeast of Guadalajara, quietly began assembling forces. Led by 27-year-old René Capistrán Garza, the leader of the Mexican Association of Catholic Youth, the region would become the main focal point of the rebellion.[citation needed]

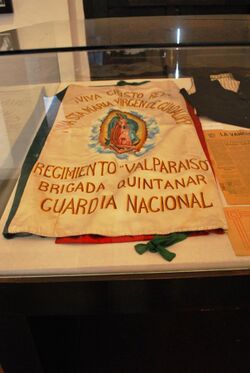

The formal rebellion began on January 1, 1927 with a manifesto sent by Garza, A la Nación ("To the Nation"). It declared that "the hour of battle has sounded" and that "the hour of victory belongs to God." With the declaration, the state of Jalisco, which had been seemingly quiet since the Guadalajara church uprising, exploded. Bands of rebels moving in the "Los Altos" region northeast of Guadalajara began seizing villages and were often armed with only ancient muskets and clubs. The Cristeros' battle cry was ¡Viva Cristo Rey! ¡Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe! (Long live Christ the King! Long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!). The rebels had scarce logistical supplies and relied heavily on the Feminine Brigades of St. Joan of Arc and raids on towns, trains, and ranches to supply themselves with money, horses, ammunition, and food. By contrast, the Calles government was supplied with arms and ammunition by the US government later in the war. In at least one battle, US pilots provided air support for the federal army against the Cristero rebels.[31]

The Calles government failed at first to take the threat seriously. The rebels did well against the agraristas, a rural militia recruited throughout Mexico, and the Social Defense forces, the local militia, but were at first always defeated by regular federal troops, who guarded the main cities. The federal army then had 79,759 men. When the Jalisco federal commander, General Jesús Ferreira, moved in on the rebels, he matter-of-factly wired to army headquarters that "it will be less a campaign than a hunt."[32] That sentiment was held also by Calles.[32]

However, the rebels planned their battles fairly well considering that most of them had little to no previous military experience. The most successful rebel leaders were Jesús Degollado, a pharmacist; Victoriano Ramírez, a ranch hand; and two priests, Aristeo Pedroza and José Reyes Vega.[33] Reyes Vega was renowned, and Cardinal Davila deemed him a "black-hearted assassin."[34] At least five priests took up arms, and many others supported them in various ways.

Many of the rebel peasants who took up arms in the fight had different motivations from the Catholic Church. Many were still fighting for agrarian land reform, which had been years earlier the focal point of the Mexican Revolution. The peasantry was still upset of the usurpation of its rightful title to the land.

The Mexican episcopate never officially supported the rebellion,[35] but the rebels had some indications that their cause was legitimate. Bishop José Francisco Orozco of Guadalajara remained with the rebels. Although he formally rejected armed rebellion, he was unwilling to leave his flock.

On February 23, 1927, the Cristeros defeated federal troops for the first time at San Francisco del Rincón, Guanajuato, followed by another victory at San Julián, Jalisco. However, they quickly began to lose in the face of superior federal forces, retreated into remote areas, and constantly fled federal soldiers. Most of the leadership of the revolt in the state of Jalisco was forced to flee to the US although Ramírez and Vega remained.

In April 1927, the leader of the civilian wing of the Cristiada, Anacleto González Flores, was captured, tortured, and killed. The media and the government declared victory, and plans were made for a re-education campaign in the areas that had rebelled. As if to prove that the rebellion was not extinguished and to avenge his death, Vega led a raid against a train carrying a shipment of money for the Bank of Mexico on April 19, 1927. The raid was a success, but Vega's brother was killed in the fighting.[34]

The "concentration" policy, [clarification needed] rather than suppressing the revolt, gave it new life, as thousands of men began to aid and join the rebels in resentment for their treatment by the government. When rains came, the peasants were allowed to return to the harvest, and there was now more support than ever for the Cristeros. By August 1927, they had consolidated their movement and had begun constant attacks on federal troops garrisoned in their towns. They would soon be joined by Enrique Gorostieta, a retired general hired by the National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty.[34] Although Gorostieta was originally a liberal and a skeptic, he eventually wore a cross around his neck and speak openly of his reliance on God.[36][citation needed]

On June 21, 1927, the first Women's Brigade was formed in Zapopan. It began with 16 women and one man, but after a few days, it grew to 135 members and soon came to number 17,000. Its mission was to obtain money, weapons, provisions, and information for the combatant men and to care for the wounded. By March 1928, some 10,000 women were involved in the struggle, with many smuggling weapons into combat zones by carrying them in carts filled with grain or cement. By the end of the war, it numbered some 25,000.[37]

With close ties to the Church and the clergy, the De La Torre family was instrumental in bringing the Cristero Movement to northern Mexico. The family, originally from Zacatecas and Guanajuato, moved to Aguascalientes and then, in 1922, to San Luis Potosí. It moved again to Tampico for economic reasons and finally to Nogales (both the Mexican city and its similarly-named sister city across the border in Arizona) to escape persecution from authorities because of its involvement in the Church and the rebels.[2]

The Cristeros maintained the upper hand throughout 1928, and in 1929, the government faced a new crisis: a revolt within army ranks that was led by Arnulfo R. Gómez in Veracruz. The Cristeros tried to take advantage by a failed attack on Guadalajara in late March 1929. The rebels managed to take Tepatitlán on April 19, but Vega was killed. The rebellion was met with equal force, and the Cristeros were soon facing divisions within their own ranks.[38][39][citation needed]

Another difficulty facing the Cristeros and especially the Catholic Church was the extended period without a place of worship. The clergy faced the fear of driving away the faithful masses by engaging in war for so long. They also lacked the overwhelming sympathy or support from many aspects of Mexican society, even among many Catholics.

Diplomacy

In October 1927, the US ambassador, Dwight E. Morrow, initiated a series of breakfast meetings with Calles at which they would discuss a range of issues from the religious uprising to oil and irrigation. That earned him the nickname "the ham and eggs diplomat" in US papers. Morrow wanted the conflict to end for regional security and to help find a solution to the oil problem in the US. He was aided in his efforts by Father John J. Burke of the National Catholic Welfare Conference. Calles's term as president was coming to an end, and ex-President Álvaro Obregón had been elected president and was scheduled to take office on December 1, 1928. Obregon had been more lenient to Catholics during his time in office than Calles, but it was also generally accepted among Mexicans, including the Cristeros, that Calles was his puppet leader.[40] Two weeks after his election, Obregón was assassinated by a Catholic radical, José de León Toral, which gravely damaged the peace process.

In September 1928, Congress named Emilio Portes Gil as interim president with a special election to be held in November 1929. Portes was more open to the Church than Calles had been and allowed Morrow and Burke to restart the peace initiative. Portes told a foreign correspondent on May 1, 1929, that "the Catholic clergy, when they wish, may renew the exercise of their rites with only one obligation, that they respect the laws of the land." The next day, the exiled Archbishop Leopoldo Ruíz y Flores issued a statement that the bishops would not demand the repeal of the laws but only their more lenient enforcement.

Morrow managed to bring the parties to agreement on June 21, 1929. His office drafted a pact called the arreglos ("agreement"), which allowed worship to resume in Mexico and granted three concessions to the Catholics. Only priests who were named by hierarchical superiors would be required to register; religious instruction in churches but not in schools would be permitted; and all citizens, including the clergy, would be allowed to make petitions to reform the laws. However, the most important parts of the agreement were that the Church would recover the right to use its properties, and priests would recover their rights to live on the properties. Legally speaking, the Church was not allowed to own real estate, and its former facilities remained federal property. However, the Church effectively took control over the properties. In the convenient arrangement for both parties, the Church ostensibly ended its support for the rebels.[citation needed]

Over the previous two years, anticlerical officers, who were hostile to the federal government for reasons other than its position on religion, had joined the rebels. When the agreement between the government and the Church was made known, only a minority of the rebels went home, mainly those who felt their battle had been won. On the other hand, since the rebels themselves had not been consulted in the talks, many felt betrayed, and some continued to fight. The Church threatened those rebels with excommunication and the rebellion gradually died out. The officers, fearing that they would be tried as traitors, tried to keep the rebellion alive. Their attempt failed, and many were captured and shot, and others escaped to San Luis Potosí, where General Saturnino Cedillo gave them refuge.[citation needed]

On June 27, 1929, church bells rang in Mexico for the first time in almost three years. The war had claimed the lives of some 90,000 people: 56,882 federals, 30,000 Cristeros, and numerous civilians and Cristeros who were killed in anticlerical raids after the war had ended.[citation needed] As promised by Portes Gil, the Calles Law remained on the books, but there were no organized federal attempts to enforce it. Nonetheless, in several localities, officials continued persecution of Catholic priests, based on their interpretation of the law.

In 1992, the Mexican government amended the constitution by granting all religious groups legal status, conceding them limited property rights, and lifting restrictions on the number of priests in the country.

US involvement

Knights of Columbus

Both US councils and the Mexican councils, mostly newly formed, of the Knights of Columbus opposed the persecution by the Mexican government. So far, nine of those beatified or canonized were Knights. The American Knights collected more than $1 million to assist exiles from Mexico, continue the education of expelled seminarians, and inform US citizens on the oppression.[41] They circulated five million leaflets educating the US about the war, held hundreds of lectures, and spread the news via radio.[41] In addition to fostering an informed public, the Knights met US President Calvin Coolidge to press for intervention.[42]

According to the Supreme Knight of the Knights of Columbus, Carl A. Anderson, two thirds of Mexican Catholic councils were shut down by the Mexican government. In response, the Knights of Columbus published posters and magazines presenting Cristero soldiers in a positive light.[43]

Ku Klux Klan

In the mid-1920s, high-ranking members of the anti-Catholic Ku Klux Klan offered Calles $10,000,000 to help fight the Catholic Church.[44] The offer came after the Knights of Columbus in the US secretly offered a group of Cristero rebels $1,000,000 in financial assistance to be used to purchase guns and ammunition – this was being done in secret after the extreme measures taken by Calles to destroy the Catholic Church. That was after Calles had also sent a private telegram to the Mexican Ambassador to France, Alberto J. Pani, to advise him that the Catholic Church in Mexico was a political movement and must be eliminated to proceed with a socialist government "free of religious hypnotism which fools the people... within one year without the sacraments, the people will forget the faith...."[45]

Aftermath

The government often did not abide by the terms of the truce. For example, it executed some 500 Cristero leaders and 5,000 other Cristeros.[46] Particularly offensive to Catholics after the supposed truce was Calles's insistence on a complete state monopoly on education, which suppressed all Catholic education and introduced secular education in its place: "We must enter and take possession of the mind of childhood, the mind of youth."[46] Calles's military persecution of Catholics would be officially condemned by Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas and the Mexican Congress in 1935.[47] Between 1935 and 1936, Cárdenas had Calles and many of his close associates arrested and forced them into exile soon afterwards.[48][49] Freedom of worship was no longer suppressed, but some states still refused to repeal Calles's policy.[50] Relations with the Church improved under President Cárdenas.[51]

The government's disregard for the Church, however, did not relent until 1940, when President Manuel Ávila Camacho, a practicing Catholic, took office.[46] Church buildings in the country still belonged to the Mexican government,[50] and the nation's policies regarding the Church still fell into federal jurisdiction. Under Camacho, the bans against Church anticlerical laws were no longer enforced anywhere in Mexico.[52]

The effects of the war on the Church were profound. Between 1926 to 1934, at least 40 priests were killed.[46] There were 4,500 priests serving the people before the rebellion, but by 1934, there were only 334 licensed by the government to serve 15 million people.[46][53] The rest had been eliminated by emigration, expulsion, and assassination.[46][54] By 1935, 17 states had no priests at all.[55]

The end of the Cristero War affected emigration to the United States. "In the aftermath of their defeat, many of the Cristeros – by some estimates as much as 5 percent of Mexico's population – fled to America. Many of them made their way to Los Angeles, where they found a protector in John Joseph Cantwell, the bishop of what was then the Los Angeles-San Diego diocese."[56] Under Archbishop Cantwell's sponsorship the Cristero refugees became a substantial community in Los Angeles, California, in 1934 staging a parade some 40,000-strong through the city.[57]

Cárdenas era

The Calles Law was repealed after Cárdenas became president in 1934.[50] Cárdenas earned respect from Pope Pius XI and befriended Mexican Archbishop Luis María Martinez,[50] a major figure in Mexico's Catholic Church who successfully persuaded Mexicans to obey the government's laws peacefully.

The Church refused to back Mexican insurgent Saturnino Cedillo's failed revolt against Cárdenas[50] although Cedillo endorsed more power for the Church.[50]

Cárdenas's government continued to suppress religion in the field of education during his administration.[46][58] The Mexican Congress amended Article 3 of the Constitution in October 1934 to include the following introductory text (textual translation): "The education imparted by the State shall be a socialist one and, in addition to excluding all religious doctrine, shall combat fanaticism and prejudices by organizing its instruction and activities in a way that shall permit the creation in youth of an exact and rational concept of the Universe and of social life."[59]

The amendment was ignored by President Manuel Ávila Camacho and was officially repealed from the Constitution in 1946.[60] Constitutional bans against the Church would not be enforced anywhere in Mexico during Camacho's presidency.[52]

The imposition of socialist education met with strong opposition in some parts of academia[61] and in areas that had been controlled by the Cristeros.

Pope Pius XI also published the encyclical Firmissimam constantiam on March 28, 1937, expressing his opposition to the "impious and corruptive school" (paragraph 22) and his support for Catholic Action in Mexico. That was the third and last encyclical published by Pius XI that referred to the religious situation in Mexico.[8]

Cristeros' crimes against school teachers

Many of those who had associated with the Cristeros took up arms again as independent rebels and were followed by some other Catholics, but unarmed public school teachers were now among the targets of independent atrocities association with the rebels.[62][63][64][65] Government supporters blamed the atrocities on the Cristeros in general.[66][67][68]

Some of the government teachers refused to leave their schools and communities, and many had their ears cut off by the Cristeros.[58][69][70][71] The teachers who were murdered and had their corpses desecrated are thus often known as maestros desorejados ("teachers without ears") in Mexico.[72][73]

In some of the worst cases, teachers were tortured and killed by the former Cristero rebels.[62][67] It is calculated that approximately 300 rural teachers were killed between 1935 and 1939,[74] and other authors calculate that at least 223 teachers were victims of the violence between 1931 and 1940,[62] including the assassinations of Carlos Sayago, Carlos Pastraña, and Librado Labastida in Teziutlán, Puebla, the hometown of President Manuel Ávila Camacho;[75][76] the execution of a teacher, Carlos Toledano, who was burned alive in Tlapacoyan, Veracruz;[77][78] and the lynching of at least 42 teachers in the state of Michoacán.[67] These atrocities have been criticized in essays and books published by the Ibero-American University in Mexico.

Today

The Mexican constitution prohibits outdoor worship unless government permission is granted. Religious organizations may not own print or electronic media outlets, government permission is required to broadcast religious ceremonies, and priests and other ministers of religion are prohibited from being political candidates or holding public office.[79]

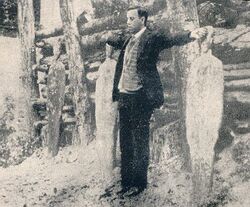

Cristero War saints

The Catholic Church has recognized several of those killed in the Cristero War as martyrs, including the Blessed Miguel Pro, a Jesuit who was shot dead without trial by a firing squad on November 23, 1927 under false charges of involvement in an assassination attempt against former President Álvaro Obregón but really for carrying out his priestly duties in defiance of the government.[80][81][82][83][84][85] His beatification occurred in 1988.

On May 21, 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized a group of 25 martyrs from the period.[86][87] They had been beatified on November 22, 1992. Of this group, 22 were secular clergy, and three were laymen.[86] They did not take up arms[87] but refused to leave their flocks and ministries and were shot or hanged by government forces for offering the sacraments.[87] Most were executed by federal forces. Although Peter de Jesus Maldonado was killed in 1937, after the war ended, he is considered to be a member of the Cristeros.[88][89][90]

The Catholic Church declared 13 additional victims of the anti-Catholic regime as martyrs on November 20, 2005, thus paving the way for their beatifications.[91] This group was mostly lay people including 14-year-old José Sánchez del Río. On November 20, 2005, at Jalisco Stadium in Guadalajara, José Saraiva Cardinal Martins celebrated the beatifications.[91]

"Battle Hymn of the Cristeros"

Juan Gutiérrez, a surviving Cristero, penned the Cristeros hymn, "Battle Hymn of the Cristeros,",l which is based on the music of the Spanish-language song "Marcha Real".[92]

- Spanish

- La Virgen María es nuestra protectora y nuestra defensora cuando hay que temer

- Vencerá a todo el demonio gritando "¡Viva Cristo Rey!" (x2)

- Soldados de Cristo: ¡Sigamos la bandera, que la cruz enseña el ejército de Dios!

- Sigamos la bandera gritando, "¡Viva Cristo Rey!"

- English translation

- The Virgin Mary is our protector and defender when there is to fear

- She will vanquish all demons at the cry of "Long live Christ the King!" (x2)

- Soldiers of Christ: Let's follow the flag, for the cross points to the army of God!

- Let's follow the flag at the cry of "Long live Christ the King!"

Other views

The French historian and researcher Jean Meyer argues that the Cristero soldiers were western peasants who tried to resist the heavy pressures of the modern bourgeois state, the Mexican Revolution, the city elites, and the rich, all of whom wanted to suppress the Catholic faith.[93]

In popular culture

"El Martes Me Fusilan" is a song by Vicente Fernandez about a fictional Cristero's execution.[94]

Juan Rulfo's famous novel Pedro Páramo is set during the Cristero War in the western Mexico city of Comala.

Graham Greene's novel The Power and the Glory is set during this period. John Ford used the novel to film his The Fugitive (1947).

Malcolm Lowry's novel Under the Volcano is also set during the period. In Lowry's novel, the Cristeros appear as a reactionary group with fascist sympathies, which contrasts with their portrayal in other novels.

There is a long section in B. Traven's novel The Treasure of the Sierra Madre that is devoted to the history of what Traven refers to as "the Christian Bandits". However, in the classic film that was based on the novel, no mention is made of the Cristeros although the novel takes place during the same time period as the rebellion.

For Greater Glory is a 2012 film based on the events of the Cristero War.

Many fact-based films, shorts, and documentaries about the war have been produced since 1929[95] such as the following:

- El coloso de mármol (1929).[96]

- Los cristeros (aka Sucedió en Jalisco) (1947).[97]

- La guerra santa (1979).[98]

- La cristiada (1986).[99]

- The Desert Within (2008) [100]

- Cristeros y federales (2011).[101]

- Los últimos cristeros (or The Last Cristeros) (2011).[102]

- Cristiada (aka For Greater Glory) (2012).[103]

See also

- Calles Law

- Catholic Church in Mexico

- Cristero Museum

- Cristóbal Magallanes Jara

- Feminine Brigades of St. Joan of Arc

- Red Shirts (Mexico)

- Kulturkampf

- List of wars involving Mexico

- Mexican Revolution

- National Action Party (Mexico)

References

- ↑ Haas, Ernst B., Nationalism, Liberalism, and Progress: The dismal fate of new nations, Cornell Univ. Press 2000

- ↑ Cronon, E. David "American Catholics and Mexican Anticlericalism, 1933–1936", pp. 205–208, Mississippi Valley Historical Review, XLV, Sept. 1948

- ↑ González, Luis, translated by John Upton translator. San José de Gracia: Mexican Village in Transition (University of Texas Press, 1982), p. 154

- ↑ Julia G. Young (2012). "Cristero Diaspora: Mexican Immigrants, the U.S. Catholic Church, and Mexico's Cristero War, 1926-29". The Catholic Historical Review (Catholic University of America Press) 98 (2): 271–300. doi:10.1353/cat.2012.0149.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Philippe Levillain (2002). The Papacy: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 1208. ISBN 9780415922302. https://archive.org/details/papacy00phil_0.

- ↑ "Acerba animi". http://www.papalencyclicals.net/Pius11/P11ANIMI.HTM.

- ↑ "Firmissimam Constantiam (March 28, 1937) | PIUS XI". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_19370328_firmissimam-constantiam_en.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pope Pius XI (1937). Firmissimam Constantiam. Libreria Editrice Vaticana. https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/pius_xi/encyclicals/documents/hf_p-xi_enc_28031937_nos-es-muy-conocida_en.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Translation made by Carlos Perez Vazquez (2005). The Political Constitution of the Mexican United States. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. http://www.juridicas.unam.mx/infjur/leg/constmex/pdf/consting.pdf.

- ↑ "Cristero Rebellion: part 1 – toward the abyss : Mexico History". http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/286-cristero-rebellion-part-1-toward-the-abyss.

- ↑ Enrique Krauze (1998). Mexico: biography of power: a history of modern Mexico, 1810–1996. HarperCollins. p. 387. ISBN 978-0-06-092917-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=sMIUcsUVyzsC.

- ↑ D. L. Riner; J. V. Sweeney (1991). Mexico: meeting the challenge. Euromoney. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-870031-59-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=2HqzAAAAIAAJ&q=%22carranza+opposed%22.

- ↑ William V. D'Antonio; Fredrick B. Pike (1964). Religion, revolution, and reform: new forces for change in Latin America. Praeger. p. 66. https://books.google.com/books?id=jEZXAAAAMAAJ&q=%22carranza+opposed%22.

- ↑ Chand, Vikram K., Mexico's political awakening, p.153, Univ. of Notre Dame Press, 2001: "In 1926, the Catholic hierarchy had responded to government persecution by suspending Mass, which was then followed by the eruption of the Cristero War...."

- ↑ Leslie Bethel Cambridge History of Latin America, p. 593, Cambridge Univ. Press: "The Revolution had finally crushed Catholicism and driven it back inside the churches, and there it stayed, still persecuted, throughout the 1930s and beyond"

- ↑ Ramón Eduardo Ruiz Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People, p. 355, W. W. Norton & Company 1993: referring to the period: "With ample cause, the church saw itself as persecuted."

- ↑ Richard Grabman, Gorostieta and the Cristiada: Mexico's Catholic Insurgency of 1926–1929, eBook, Editorial Mazatlán, 2012

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Martin Austin Nesvig, Religious Culture in Modern Mexico, pp. 228–29, Rowman & Littlefield, 2007

- ↑ Michael J. Gonzales (2002). The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1940. UNM Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-8263-2780-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=se17aQLbKioC&q=eduardo+tamariz+huerta.

- ↑ Roy Palmer Domenico (2006). Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Politics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-313-32362-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=Z8ZixRcQfV8C&q=eduardo+tamariz+huerta.

- ↑ Samuel Brunk (1995). Emiliano Zapata: Revolution & Betrayal in Mexico. UNM Press. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8263-1620-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=hfCegmr-0c4C&q=parish+priests.

- ↑ Albert P. Rolls (2011). Emiliano Zapata: A Biography. ABC-CLIO. p. 145. ISBN 9780313380808. https://books.google.com/books?id=U6jQgcU7RJoC&q=zapata+catholic.

- ↑ John Lear (2001). Workers, neighbors, and citizens: the revolution in Mexico City. University of Nebraska Press. p. 261. ISBN 978-0-8032-7997-1. https://archive.org/details/workersneighbors0000lear.

- ↑ Robert P. Millon (1995). Zapata: The Ideology of a Peasant Revolutionary. International Publishers Co. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7178-0710-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=H4Ns7fLUZ9gC&q=huerta+catholic+clergy+.

- ↑ Peter Gran (1996). Beyond Eurocentrism: a new view of modern world history. Syracuse University Press. p. 165. ISBN 978-0-8156-2692-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=_IZpnL4XW3sC&q=clergy+supported+huerta.

- ↑ Gonzales, Michael J., The Mexican Revolution, 1910–1940, p. 268, UNM Press, 2002

- ↑ David A. Shirk, Mexico's New Politics: The PAN and Democratic Change p. 58 (L. Rienner Publishers 2005)

- ↑ Tuck, Jim The Cristero Rebellion – Part 1 Mexico Connect 1996

- ↑ "Mexico – Religion". http://countrystudies.us/mexico/61.htm.

- ↑ John W. Warnock, The Other Mexico: The North American Triangle Completed p. 27 (1995 Black Rose Books, Ltd); ISBN:978-1-55164-028-0

- ↑ Christopher Check. "The Cristeros and the Mexican Martyrs" ; This Rock; p. 17; September 2007; Accessed May 21, 2011

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Jim Tuck, The Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico's Cristero Rebellion, p. 55, University of Arizona Press, 1982

- ↑ "The Anti-clerical Who Led a Catholic Rebellion", Latin American Studies

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Jim Tuck, The Anti-clerical Who Led a Catholic Rebellion, Latin American Studies

- ↑ Roy P. Domenico, Encyclopedia of Modern Christian Politics, p. 151, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006

- ↑ "University of Texas". http://www.laits.utexas.edu/jaime/cwp5/crg/english/gorostieta/.

- ↑ Meyer, Jean A. (1976). The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People between Church and State, 1926–1929. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 132, 133, 136. ISBN 9780521210317.

- ↑ Kourf, Professor (November 27, 2002). U.S. Reaction Towards the Cristero Rebellion. Dalageorgas, Kosta. https://www.academia.edu/3548280.

- ↑ On June 2, Gorostieta was killed in an ambush by a federal patrol. However, the rebels now had some 50,000 men under arms and seemed poised to draw out the rebellion for a long time.

- ↑ Enrique Krauze (1997). Mexico: Biography of Power: A History of Modern Mexico, 1810–1996. New York: HarperCollins. p. 399. ISBN 978-0-06-016325-9. https://archive.org/details/mexico00enri/page/399.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 The Story, Martyrs, and Lessons of the Cristero War: An interview with Ruben Quezada about the Cristiada and the bloody Cristero War (1926–1929), Catholic World Report, June 1, 2012

- ↑ Don M. Coerver, Book Review: Church, State, and Civil War in Revolutionary Mexico, Volume 31, Issue 03, pp. 575–578, 2007

- ↑ Interview. For Greater Glory Film documentary. May 2012.

- ↑ Letters found in Calles' library

- ↑ Jean Meyer, La Cristiada: A Mexican People's War for Religious Liberty, ISBN:978-0-7570-0315-8. SquareOne Publishers.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 46.2 46.3 46.4 46.5 46.6 Van Hove, Brian Blood-Drenched Altars Faith & Reason 1994

- ↑ "MEXICO: Ossy, Ossy, Boneheads". 4 February 1935. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,788523-1,00.html.

- ↑ "MEXICO: Cardenas v. Malta Fever". 25 November 1935. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,755388,00.html.

- ↑ "MEXICO: Solution Without Blood". 20 April 1936. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,848503,00.html.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 50.5 "Religion: Where Is He?". Time. December 26, 1938. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,772205-4,00.html.

- ↑ "Mexico – Cardenismo and the Revolution Rekindled". http://countrystudies.us/mexico/34.htm.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Sarasota Herald-Tribune, "Mexico Fails To Act on Church Law", February 19, 1951

- ↑ Hodges, Donald Clark, Mexico, the end of the revolution, p. 50, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2002

- ↑ Scheina, Robert L. Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899 p. 33 (2003); ISBN:978-1-57488-452-4

- ↑ Ruiz, Ramón Eduardo Triumphs and Tragedy: A History of the Mexican People p. 393, (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1993); ISBN:978-0-393-31066-5

- ↑ Rieff, David; "Nuevo Catholics"; The New York Times Magazine; December 24, 2006.

- ↑ Rieff, David Los Angeles: Capital of the Third World London 1992 p. 164 ISBN:978-0-224-03304-6

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Donald Clark Hodges; Daniel Ross Gandy; Ross Gandy (2002). Mexico, the end of the revolution. Praeger. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-275-97333-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=7prW3gXbFRgC&q=persecution+cristeros+teachers.

- ↑ George C. Booth (1941). Mexico's school-made society. Stanford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-8047-0352-9. https://archive.org/details/mexicosschoolmad00boot.

- ↑ Berd, Malcolm D. (1983). The origins, implementation, and the demise of socialist education in Mexico, 1932–1946.

- ↑ Sarah L. Babb (2004). Managing Mexico: Economists from Nationalism to Neoliberalism. Princeton University Press. p. 55. ISBN 978-0-691-11793-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=dkoVCvyqoo0C&q=marxism+unam+strike.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 John W. Sherman (1997). The Mexican right: the end of revolutionary reform, 1929–1940. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 43–45. ISBN 978-0-275-95736-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=h29VKMtmzzcC&q=%22alleged%20cristeros%22+teachers.

- ↑ Carlos Monsiváis; John Kraniauskas (1997). Mexican postcards. Verso. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-86091-604-8. https://archive.org/details/mexicanpostcards0000mons.

- ↑ Guillermo Zermeño P. (1992). Religión, política y sociedad: el sinarquismo y la iglesia en México; Nueve Ensayos. Universidad Iberoamericana. p. 39. ISBN 978-968-859-091-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=8E_bBnLjKZkC&q=quemados+desorejados.

- ↑ Ponce Alcocer et al. (2009). El oficio de una vida: Raymond Buve, un historiador mexicanista. Universidad Iberoamericana. p. 210. ISBN 978-607-417-009-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=XkYxtIFH47sC&q=desorejados.

- ↑ Christopher Robert Boyer (2003). Becoming campesinos: politics, identity, and agrarian struggle in postrevolutionary Michoacán, 1920–1935. Stanford University Press. pp. 179–81. ISBN 978-0-8047-4356-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=wij7fa771i0C&q=cristeros+teachers.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Marjorie Becker (1995). Setting the Virgin on fire: Lázaro Cárdenas, Michoacán peasants, and the redemption of the Mexican Revolution. University of California Press. pp. 124–126. ISBN 978-0-520-08419-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=poCw5DcQF5cC&q=cristeros+teachers.

- ↑ Cora Govers (2006). Performing the community: representation, ritual and reciprocity in the Totonac Highlands of Mexico. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 132. ISBN 978-3-8258-9751-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=4y4KnORm320C&q=cristeros+teachers.

- ↑ George I. Sanchez (2008). Mexico – A Revolution by Education. Read Books. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-4437-2587-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=mniza5YPT8wC&q=cristeros+teachers+ears.

- ↑ Raquel Sosa Elízaga (1996). Los códigos ocultos del cardenismo: un estudio de la violencia política, el cambio social y la continuidad institucional. Plaza y Valdes. p. 333. ISBN 978-968-856-465-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=jnHvmRfNwOsC&q=maestros+desorejados.

- ↑ Everardo Escárcega López (1990). Historia de la cuestión agraria mexicana, Volumen 5. Siglo XXI. p. 20. ISBN 978-968-23-1492-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=RIr9q05GvzQC&q=desorejados+cristeros.

- ↑ Matthew Butler; Matthew John Blakemore Butler (2007). Faith and impiety in revolutionary Mexico. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-4039-8381-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=PtCtFTtvoV0C.

- ↑ Kees Koonings; Dirk Kruijt (1999). Societies of fear: the legacy of civil war, violence and terror in Latin America. Zed Books. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-85649-767-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=mCdsSrteGGoC&q=teachers+killed+raped+desorejados.

- ↑ Nathaniel Weyl; Mrs. Sylvia Castleton Weyl (1939). The reconquest of Mexico: the years of Lázaro Cárdenas. Oxford university press. p. 322. https://books.google.com/books?id=9UkVAAAAYAAJ&q=almost+300+rural+teachers.

- ↑ Eric Van Young; Gisela von Wobeser (1992). La ciudad y el campo en la historia de México: memoria de la VII Reunión de Historiadores Mexicanos y Norteamericanos (in English). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. p. 896. ISBN 978-968-36-1865-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=a-C7AAAAIAAJ&q=cristeros+teachers.

- ↑ "Special Correspondence". School & Society (Society for the Advancement of Education) 44: 739–41. 1936. https://books.google.com/books?id=CzM5AAAAMAAJ&q=teachers+cristeros+.

- ↑ Belinda Arteaga (2002). A gritos y sombrerazos: historia de los debates sobre educación sexual en México, 1906–1946 (in Spanish). Miguel Angel Porrua. p. 161. ISBN 978-970-701-217-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=Af6FAAAAIAAJ&q=vivo+carlos+toledano+.

- ↑ Eduardo J. Correa (1941). El balance del cardenismo. Talleres linotipográficos "Acción". p. 317. https://books.google.com/books?id=iaT-nugaHSIC&q=quemado+maestro+rural+toledano+.

- ↑ Soberanes Fernandez, José Luis, Mexico and the 1981 United Nations Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief, pp. 437–438 nn. 7–8, BYU Law Review, June 2002

- ↑ Bethell, Leslie, The Cambridge History of Latin America, p. 593, Cambridge University Press, 1986

- ↑ Commire, Anne. Historic World Leaders: North & South America (M-Z), p. 628, Gale Research Inc., 1994

- ↑ Profile of Miguel Pro, p. 714, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1986

- ↑ Wright, Jonathan, God's Soldiers: Adventure, Politics, Intrigue, and Power – A History of the Jesuits, p. 267, Doubleday 2005

- ↑ Greene, Graham, The Lawless Roads, p. 20, Penguin, 1982

- ↑ Blesses Miguel Pro Juarez, Priest and Martyr(Catholic News Agency 2007)

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 ""Homily of Pope John Paul II: Canonization of 27 New Saints". May 21, 2000". https://www.vatican.va/holy_father/john_paul_ii/homilies/documents/hf_jp-ii_hom_20000521_canonizations_en.html.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 87.2 Gerzon-Kessler, Ari, "Cristero Martyrs, Jalisco Nun To Attain Sainthood" . Guadalajara Reporter. May 12, 2000

- ↑ "Martiri Messicani". https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_academies/cult-martyrum/martiri/013.html.

- ↑ "Pedro de Jesús Maldonado Lucero". https://www.vatican.va/news_services/liturgy/saints/ns_lit_doc_20000521_maldonado-lucero_sp.html.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 "14-year-old Mexican martyr to be beatified Sunday"; Catholic News Agency; November 5, 2005

- ↑ Marc Kropfl (30 October 2006). "Juan Guitierrez "Original Cristero Soldier"". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qrFK9nzgAB8.

- ↑ Meyer cited in Donald J. Mabry, "Mexican Anticlerics, Bishops, Cristeros, and the Devout during the 1920s: A Scholarly Debate", Journal of Church and State (1978) 20#1 pp. 81–92

- ↑ "El Martes Me Fuzilan – Vicente Fernandez". https://www.letras.com/vicente-fernandez/1300723/.

- ↑ Jean Meyer, Ulises Íñiguez Mendoza (2007). La Cristiada en imágenes: del cine mudo al video. Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico

- ↑ Manuel R. Ojeda (1929). El coloso de mármol. Mexico

- ↑ Raúl de Anda (1947). Los Cristeros. Mexico

- ↑ Carlos Enrique Taboada (1979). La guerra santa. Mexico

- ↑ Nicolás Echevarría (1986). La cristiada. Mexico

- ↑ Rodrigo Pla (2008). Desierto Adentro. Mexico

- ↑ Isabel Cristina Fregoso (2011). Cristeros y Federales

- ↑ Matias Meyer (2011). The Last Christeros

- ↑ "Eduardo Verastegui to play Mexican martyr in 'Cristiada'". October 7, 2010. Catholic News Agency

103. Meade, Teresa A. History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Wiley-Blackwell, 2016.

Sources

- Bailey, David C. Viva Cristo Rey! The Cristero Rebellion and the Church-State Conflict in Mexico (1974); 376pp; a standard scholarly history

- Butler, Matthew. Popular Piety and political identity in Mexico's Cristero Rebellion: Michoacán, 1927–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Ellis, L. Ethan. " Dwight Morrow and the Church-State Controversy in Mexico", Hispanic American Historical Review (1958) 38#4 pp. 482–505 in JSTOR

- Espinosa, David. "'Restoring Christian Social Order': The Mexican Catholic Youth Association (1913–1932)", The Americas (2003) 59#4 pp. 451–474 in JSTOR

- Jrade, Ramon. "Inquiries into the Cristero Insurrection against the Mexican Revolution", Latin American Research Review (1985) 20#2 pp. 53–69 in JSTOR

- Meyer, Jean. The Cristero Rebellion: The Mexican People between Church and State, 1926–1929. Cambridge, 1976.

- Miller, Sr. Barbara. "The Role of Women in the Mexican Cristero Rebellion: Las Señoras y Las Religiosas", The Americas (1984) 40#3 pp. 303–323 in JSTOR

- Lawrence, Mark. 2020. Insurgency, Counter-insurgency and Policing in Centre-West Mexico, 1926–1929. Bloomsbury.

- Purnell, Jenny. Popular Movements and State Formation in Revolutionary Mexico: The Agraristas and Cristeros of Michoacán. Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Quirk, Robert E. The Mexican Revolution and the Catholic Church, 1910–1929, Greenwood Press, 1986.

- Tuck, Jim. The Holy War in Los Altos: A Regional Analysis of Mexico's Cristero Rebellion. University of Arizona Press, 1982. ISBN:978-0-8165-0779-5

- Young, Julia. Mexican Exodus: Emigrants, Exiles, and Refugees of the Cristero War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Historiography

- Mabry, Donald J. "Mexican Anticlerics, Bishops, Cristeros, and the Devout during the 1920s: A Scholarly Debate", Journal of Church and State (1978) 20#1 pp. 81–92 online

In fiction

- Luis Gonzalez – Translated by John Upton. San Jose de Gracia: Mexican Village in Transition ISBN:978-0-292-77571-8 (historical novel), Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 1982.

- Greene, Graham. The Power and the Glory (novel). New York: Viking Press, 1940 (as The Labyrinthine Ways).

In Spanish

- De La Torre, José Luis. De Sonora al Cielo: Biografía del Excelentísimo Sr. Vicario General de la Arquidiócesis de Hermosillo, Sonora Pbro. Don Ignacio De La Torre Uribarren (Spanish Edition)[3]

External links

- Cristeros (Soldiers of Christ) – Documentary

- The Cristero Rebellion, by Jim Tuck

- AP article on the 2000 canonizations

- Biography of Miguel Pro

- Spanish article on the war

- Spanish biographies of the saints canonized in 2000

- Ferreira, Cornelia R. Blessed José Luis Sánchez del Rio: Cristero Boy Martyr, biography (2006 Canisius Books).

- Iniquis Afflictisque – encyclical of Pope Pius XI on the persecution of the Church in Mexico (November 18, 1926)

- Miss Mexico wears dress depicting Cristeros at the 2007 Miss Universe Pageant

- Catholicism.org: "Valor and Betrayal – The Historical Background and Story of the Cristeros" – article by Gary Potter.