Biography:Thomas Hall (inventor)

Thomas Hall | |

|---|---|

c. 1880 | |

| Born | Norwich, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 11 June 1919 (aged 93) Cincinnati, Ohio, United States |

| Known for | Electrical instruments |

Thomas Hall (April 20, 1826 – June 11, 1919) was an American mechanic, physicist, inventor and manufacturer. He worked with the inventor Daniel Davis for many years co-inventing electric and telegraph equipment. He later ran his own business, manufacturing and selling electric components, electromagnetic devices and telegraph apparatus. He received many gold and silver medals for his innovations. One of his electricity experiments was a toy model-size electric locomotive that got its power directly off the tracks it was running on, which was a new concept and technology at the time. He was mostly associated with Boston and the area.

Early life

Hall was born in Norwich, England, on April 20, 1826. He was named after his father, who was a physician. In 1828, the family moved from England to Boston. Hall had five siblings: three brothers and two sisters. In 1833, he first went to the public school at the corner of Dover and Washington streets where a Miss Miller was the teacher. In 1834 Hall entered the Franklin School, a private institution. The teachers there were Richard Green Parker, Miss. Marden, Miss. Barry, Mrs. Pierce and Mrs. Bascomb. In 1836, Hall attended the East Street school. Later he attended Eliot School in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood where his father's practice was from.[1]

Career

Hall was indentured by his father to an electrician, Daniel Davis, in 1840 when he was 14 years old. Davis at the time was located at 11 Cornhill Avenue and in 1844 moved his business to 528 Washington Street. Together they constructed the first telegraph devices for Samuel Morse in 1844. After that they made other telegraph-related parts, including sounders, keys, and registers. Hall was the first man in America to teach the skill of telegraphy. At the time, he was involved in inventing the protective relay, lightning arrester, electric magneto and an electric railroad signal. Being a skillful electrical technician and mechanical engineer, he constructed many of Dr. Charles Grafton Page's inventions.[2] Many of his inventions were used by the public and railroads for decades.[3]

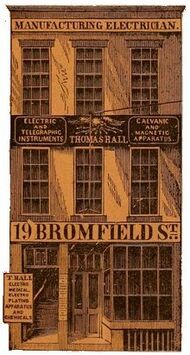

Hall with George W. Palmer bought out Davis's business in 1848 and formed Palmer & Hall. In 1856 he bought out Palmer's interest and the business was then known as "Thomas Hall / Magnetical & Telegraphic Instrument Maker".[4] That firm continued in business until 1892 when Hall brought his son into the firm and the name became Thomas Hall & Son. Their place of business was 19 Bromfield Street in Boston. There they made all kinds of electromagnetic apparatus and school experimentation equipment for physics and chemistry classes.[5] They also made electric devices for medical use, including Hall's New French Battery.[6]

Hall invented electrical mechanical apparatus while in business and became a well-known manufacturer of these type of apparatus in Boston.[7] One device was an electric stop on a paper-ruling machine and another was an electric valve used in milk creameries to keep milk at a constant temperature for cream separation and processing butter. Another electrical mechanical device he invented was an electric recorder for measuring at a pumping station the water height or gas height in a reservoir. He also invented a life raft that took his name. His work brought him a number of American gold and silver medals. In 1867 at the Paris Exposition, he earned a medal for his electric railroad signal. Most of his work was experimental and costly. He was never able to make a large amount of money from his inventions. They did however bring him into acquaintance with many of the prominent inventors and businessmen of the electrical and scientific fields throughout America in the nineteenth century.[3]

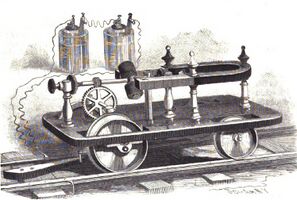

Below are images of typical battery and electromagnetic apparatus for the electrical field manufactured and sold in 1861 by Hall from his catalogue of products.[8]

Electric locomotives

At the age of 24, Hall constructed a toy model experimental electric locomotive which took its electric power from the tracks.[9][10][11] The electricity came from two batteries located on the second story of the exhibit building about 200 feet (61 m) away from the tracks.[12][13] This train set was shown in Palmer & Hall's 1850 catalogue.[14][15] The tracks for the train were straight and about 20 feet (6.1 m) long.[16] It was arranged to automatically switch polarity on the battery current when it got to the end of the track and run in reverse returning to where it started.[13][17][18] Hall exhibited this model train with a reciprocating engine in 1851 at the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanics Fair in Boston's Faneuil Hall.[19] The tracks for the model train were connected to stationary batteries. This was the first public demonstration of electric current being supplied from the railroad tracks to the motor of the electric locomotive instead of onboard batteries.[20] It was the first instance of rolling contacts being used from a stationary electric power source.[21] It was also the first time an electric railway was made that operated by wheels or trolleys that received received its electric power from the tracks it was riding on.[13][22]

The main reason for having stationary batteries in one place away from the locomotive was so the batteries would not be damaged, which usually happened when the batteries were mounted in the moving vehicle. This toy electric train was sold as a scientific apparatus.[23] The electric power was furnished by two Grove battery cells that were wired directly to the rails. The electric power to run the engine was picked up off the tracks through the steel wheels, with one track having the positive charge and the other track having the negative charge.[20] In 1860 he exhibited on a circular track in Quincy Hall in Boston an advanced version of this model train called the Volta that was constructed like a steam locomotive.[3] This time the direct current electric power was furnished from a dynamo generator instead of batteries and that machinery after the exhibition went to the physical laboratory at Harvard College.[13]

The practice of having the electric power source away from the locomotive was so common throughout the United States by 1888 it attracted little attention. This showed how little this technology of having a distant stationary electric power source had changed in 50 years.[14] Hall had conveyed the electrical current to his 1851 toy locomotive through several feet of rail using the rail as the electrical conductor from a power source yards away. Edison did basically the same thing some 30 years later in his historic electric railroad experiments at Menlo Park with a power source blocks away.[24] Most trolleys on the streets in the cities of the United States by 1910 were receiving their electrical power to operate from a distant power station miles away.[15]

Hall made in 1852, for a Dr A. L. Henderson of Buffalo, New York, a model railroad train set complete with an electric locomotive, telegraph line, electric railroad signals and miniature depots. Scaled down toy figures operated the signals at each end of the telegraph line automatically.[14] This was the first instance of any electric railroad train being controlled by telegraph signals.[15]

Personal life and death

Hall married Julia W. Beals of Bath, Maine, in 1853. They had three boys. He was a mason belonging to the Fraternity Lodge of Newtonville Massachusetts, a member of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association, and a member of the Boston City Guards. He belonged to the Franklin School Association, Veteran Association of Mechanics Apprentices Library, and the Old School Boys Association.[1]

Hall lived in Auburndale, Massachusetts, in the 1890s when he retired.[1] He lived with a son in the Madisonville neighborhood of Cincinnati from 1902.[3] He died there on June 11, 1919.[25]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brayley 1894, p. 209.

- ↑ Brackett 1890, p. 40.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Electrical World 1906, p. 852.

- ↑ Harvard University 2022, p. 1.

- ↑ "May yet Talk with Stars". The Boston Globe (Boston, Massachusetts): p. 60. May 28, 1916. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/100072281/.

- ↑ Hall 1880, pp. 2–99.

- ↑ Manning 2022, p. 1.

- ↑ Hall 1861, p. 20.

- ↑ Whipple 1889, p. 90.

- ↑ King 1962, p. 267.

- ↑ "Development of Electric Railways". The Independent Record (Helena, Montana): p. 4. October 30, 1907. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/100202669/.

- ↑ Railway Mechanic 1885, p. 22.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 "The Greenace Lectures". Boston Evening Transcript (Boston, Massachusetts): p. 6. August 2, 1897. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/100261364/.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Martin 1892, p. 20.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Dyer 1910, p. 101.

- ↑ Electrical Review 1885, p. 69.

- ↑ Luce 1886, p. 36.

- ↑ DePew 1895, p. 343.

- ↑ Dyer 2019, p. 65.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "September 1 in History - First Electric Railway". The Oregon Daily Journal (Portland, Oregon): p. 8. September 1, 1910. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/99933148/. "The same year Thomas Hall of Boston built a small electric locomotive, called the Volta. The current was furnished by two Grove battery cells conducted to the rails, thence through the wheels of the locomotive to the motor. This was the first instance of the current being supplied to the motor on a locomotive from a stationary source."

- ↑ "The Progress of Electricity". The Commercial Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee): p. 26. February 10, 1901. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/99936487/.

- ↑ Trevert 1892, p. 146.

- ↑ "The History of the Nineteenth Century Electricity". Washington Times (Washington, District of Columbia): p. 8. February 10, 1901. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/99935730/.

- ↑ Hungerford 1928, p. 86.

- ↑ 121 Meeting 1916, p. 50.

Sources

- 121 Meeting, Proceedings of annual meeting (January 19, 1916). One Hundred Years American Commerce. Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association. p. 50. https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=cAA0AQAAMAAJ&pg=GBS.RA4-PA50&hl=en.

- Brackett, Cyrus Fogg (1890). Electricity in Daily Life. C. Scribner's sons. p. 40. OCLC 2403777. https://books.google.com/books?id=rnlYwxqUS6MC&dq=%22Thomas+Hall+of+Boston+a+skilful+electromechanic+who+had+constructed+much+of+Page%27s+apparatus+made+a+small+model+of+an+electric+locomotive+and+car+which+is+not+without+scientific+interest+as+establishing+the+practicability+of+conveying+the+electric+current+to+a+rapidly+moving+railway+car+by+employing+the+rails+and+wheels+as+electrical+conductors+thus+dispensing+with+the+necessity+of+transporting+the+battery+upon+the+vehicle%22&pg=PA40.

- DePew, Chauncey Mitchell (1895). One Hundred Years American Commerce. D.O. Haynes. p. 343. OCLC 1195468396. https://www.google.com/books/edition/1795_1895_One_Hundred_Years_of_American/z8gJAAAAIAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Thomas+Hall+(inventor)+electric+locomotive+volta&pg=PA343&printsec=frontcover.

- Brayley, Arthur Wellington (1894). Schools & Schoolboys of Old Boston. L. P. Hager. p. 209. OCLC 680441827. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Schools_and_Schoolboys_of_Old_Boston/tNc-AAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Was+born+in+Norwich+Eng+April+20+1826+His+father+whose+name+was+also+Thomas%22&pg=PA209&printsec=frontcover.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: - Dyer, Thomas C. (1910). Edison, His Life and Inventions. Harper & Brothers. p. 65. OCLC 473117943.

- Dyer, Thomas C. (2019). Edison, His Life and Inventions. Outlook Verlag. p. 65. ISBN 9783734058783. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Edison_His_Life_and_Inventions/MvSxDwAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Palmer+%26+Hall%22+catalogue+1850&pg=PA65&printsec=frontcover.

- Hall, Thomas (1861). Illustrated catalogue of electro-medical instruments: manufactured and sold by Thomas Hall. Wright & Potter, printers. p. 20. OCLC 956537914. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/tda84cv6/items?canvas=20.

- Hall, Thomas (1880). Hall's New Patent French Battery. Thomas Hall. p. 2–99. OCLC 31525588.

- Harvard University (2022). "Thomas Hall fl. 1840-1875". Harvard University. http://waywiser.fas.harvard.edu/people/943/thomas-hall.

- Hungerford, Edward (1928). The Story of Public Utilities. G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 806373074.

- King, W. James (1962). Development of electrical technology in nineteenth century. U.S. National Museum. Bulletin 228. Smithsonian Institute. OCLC 636802960. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uiug.30112106772665&view=1up&seq=39&skin=2021&q1=Thomas%20Hall.

- Luce, Robert (1886). Electric Railways & Electric Transmission. W.H. Harris & Company. p. 36. OCLC 11847293. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Electric_Railways_and_the_Electric_Trans/xEqDSckt8q0C?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22In+1851+Thomas+Hall+of+Boston+constructed+and+later+exhibited+at+the+Charitable+Mechanics+Fair+in+Boston+a+small+electric+locomotive+which+took+its+current+from+a+stationary+battery+by+means+of+the+rails+and+wheels+The+cut+off+was+in+the+engine+and+worked+automatically+or+by+hand+so+that+when+the+engine+reached+the+end+of+the+track+the+switch+reversed+it+and+it+went+back+to+the+starting+point%22&pg=PA36&printsec=frontcover.

- Manning, Kenneth R. (2022). "Culture of Invention in Boston". Rutgers University. https://edison.rutgers.edu/resources/latimer/the-culture-of-invention-in-boston.

- Martin, Thomas C. (1892). The Electric Motor. W. J. Johnson.

- Electrical Review (1885). "Electrical Railways". The Telegraphic Journal and Electrical Review 16: 65. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Electrical_Review/ZutQAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=straight+tracks+were+about+20+feet+long.+%22Thomas+Hall%22+electric+locomotive&pg=PA69&printsec=frontcover.

- Electrical World (1906). "Personal - Mr. Thomas Hall". Electrical World (McGraw-Hill) 47 (16): 852. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=uva.x002212096&view=1up&seq=866&skin=2021&q1=%22Thomas%20Hall%22.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: - Railway Mechanic (1885). "Development of Electricity as a Meter". Railway Master Mechanic (Simmons-Boardman Publishing Company) 8. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Railway_Master_Mechanic/fWw9AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=The+current+was+conducted+the+insulated+wheels+from+two+Grove+batteries&pg=PA22&printsec=frontcover.

- Trevert, Edward (1892). Electric Railway Engineering. Bubier Publishing Company. p. 142. OCLC 22750915. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Electric_Railway_Engineering/stoPAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=Thomas+Hall+(inventor)+electric+locomotive+volta&pg=PA146&printsec=frontcover.

- Whipple, Fred H. (1889). The Electric Railway. The Lewis & Power Mfg Company. OCLC 913150527. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Electric_Railway/XdYEAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=%22Mr+Thomas+Hall+a+scientific+instrument+maker+built+a+small+model+of+an+electric+locomotive+and+successfully+ran+it+taking+the+electricity+from+the+rails%22&pg=PA90&printsec=frontcover.