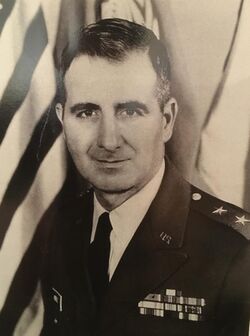

Biography:Charles C. Noble

Charles Carmin Noble (May 18, 1916 – August 16, 2003) was an American major general and engineer who worked on the Manhattan Project, led construction in Nuremberg after World War II, developed the early American ICBM program, was the chief engineer in the Vietnam War, and made the controversial yet successful decision to open Morganza Spillway in northern Louisiana for the first time to relieve pressure upstream and save New Orleans during the 1973 Mississippi Flood.

Early life and education

Charles "Chuck" Carmin Noble was born on May 18, 1916, in Syracuse New York of Italian immigrants Anthony Noto and Julia Samarra. Both Anthony and Julia immigrated from Italy through Ellis Island. Later the family changed their name to Noble during World War II to avoid recognition of their Italian heritage. The family worked in the coal mines and had no wealth reserves so even though Charles was an excellent student and desired additional education the family was not able to pay for more schooling. Noble desired to enter the military as a vehicle for advancement in life later reflecting that "You must have long term goals to keep you from being frustrated by short term failures."[1] Noble enrolled in the Army Preparatory School at Fort Totten, after high school hoping that it might help him obtain an appointment to West Point. Noble later elected to take the national merit exam scoring the highest mark in the nation which allowed him admission to West Point and Annapolis. Charles chose West Point, and entered the academy on 1 Jul 1936.[2] He graduated in 1940.

World War II

Shortly after graduation he went to Fort Belvoir, Virginia where he met Edith Margaret Lane and after a whirlwind romance married her just prior to World War II. When America entered World War II, Noble was secretly sent to Oak Ridge, Tennessee to work on plutonium production for the atomic bomb. Noble was appointed executive officer of the Manhattan District and executive secretary to the Military Liaison Committee of the United States Atomic Energy Commission. As the plutonium production went online Noble desired to move up in rank and requested to join combat duty before the war ended. Noble joined George Patton's Third Army commanding the 1271st Engineering Battalion in Ardennes-Alscace, Rhineland, and Centra1 Europe campaign. He also participated in the liberation of a concentration camp.[3] As an engineer, Noble commanded the 288th Engineer Battalion and during post-hostilities occupation was assigned to the reconstruction of the Nuremberg trial facilities and building apartments for Jewish refugees.[4]

Cold War

After the war ended, Noble was sent by the army to M.I.T. where he earned a master's degree in civil engineering.[3] He then returned to the Manhattan District, Army Engineers atomic-energy project, in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.[5] prior to working for the Pentagon until 1949. After the Berlin Crisis and the ensuing establishment of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Noble was transferred to Paris, France to coordinate with General Eisenhower at Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers Europe (SHAPE) headquarters. Noble was integral in the planning and operations division and held the office of the special assistant to the chief of staff, General Cortlandt V.R. Schuyler. His family joined him in 1950 and they lived in Paris working with NATO until 1954.

In 1954 the Nobles returned to New York as Noble was assigned as deputy district engineer at the New York Engineer District for the next two years. Following this Noble attended the army war college in Carlisle, Pennsylvania for nine months. With the Sputnik scare and resulting emphasis on missile and rocketry Noble was transferred into the army engineering missile program where he directed the Atlas and Minuteman ICBM Base Construction Program in the western United States between 1960 and 1963.[6] During this period Colonel Noble, as deputy commander of the Corps of Engineers Ballistic Missile Construction Office (CEBMCO),[7] won the Wheeler Medal for outstanding contribution to military engineering as director of the Atlas and Minute man construction programs.[8] He was then assigned to the National War College, where he earned another master's degree, this one in international affairs, from George Washington University. Noble continued his engineering career as colonel and served as the director of civil works in the Office of the Chief of engineers at The Pentagon.

Noble served as chief engineer in three theaters: UNC/US Forces in Korea from 1964 to 1966, U.S. Army Europe from 1969 to 1970; and finally U.S. Army Vietnam from 1970 to 1971.

Panama and the Vietnam War

As chief engineer for civil works, Noble was also charged with submitting a report on the expansion of the Panama Canal and the possible construction of a sea-level canal. With serious consideration being given to employing nuclear excavation technology the commission headed by Noble recommended strongly against the idea when they submitted their report in November 1970. He noted that such a plan would involve relocating the local population and possibly create long-term environmental damage from radioactivity.[9]

With the Vietnam War escalating, Noble was awarded the rank of major general and on June 25, 1970, assumed command of US Army Engineer Command in the Republic of Vietnam.[10] He received several Army Distinguished Service Medals and Legion of Merit awards for service in Vietnam.[11]

Mississippi River flood control

With the war winding down in 1971, President Nixon appointed him president of the Mississippi River Commission. Noble directed Corps of Engineers activities during the great Mississippi flood of 1973 of the Mississippi River which was one of the century's greatest floods. Confronted with a potential disaster due to the collapse of the Old River Control Structure Noble took decisive action.[3] Noble ordered the opening of all 350 panels of the Bonnet Carré Spillway Dam which diverted a portion of the Mississippi through a 5.7 trough of low land to the Gulf of Mexico resulting in an easing of the pressure on levees and the protection of New Orleans.[12] Noble retired from active duty in August 1974 obtaining the rank of major general.[3]

Retirement and passing

After retirement, Noble joined the Charles T Main Engineering Company in Boston, where he managed engineering projects across the globe.

Noble's initial focus was on MAIN's water resource studies. Early on Noble understood the importance of water for the future stating, "Water's the future of gold and oil combined."[13] He retired from Charles T Main as president and chief executive officer in 1984.[6] In retirement Noble spent hours gardening and working on upgrading his upstate New York family camp. He continued to work hard as he had during his long military service and engineering career living the life he noted in his famous quote "first we make our habits, then our habits make us."[14]

Noble died on Aug. 16, 2003 and was interred in Arlington National Cemetery.[15] Noble was listed in "Engineers of Distinction", "Who's Who in Engineering," "Who's Who in America," and for his military service won three Distinguished Service Medals with two oak leaf clusters, three awards of the Legion of Merit with two oak leaf clusters, and bronze star. He fathered five children, four of whom survive including Jeanne Davey (b. 1943), Barbara (Lynn) Noble (b. 1947), Carol Noble (b. 1950), and Steve Noble (b. 1952).[16]

References

- ↑ "Charles C. Noble". http://happitivity.com/quote-author/charles-c-noble/.

- ↑ Charles Noble Memorial Tributes: Volume 12. The National Academies Press. 2008. doi:10.17226/12473. ISBN 978-0-309-12639-7. https://www.nap.edu/read/12473/chapter/38.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "August 21, 2003 – The Vicksburg Post". 21 August 2003. http://www.vicksburgpost.com/2003/08/21/august-21-2003/.

- ↑ Davey, Jeanne. Personal recollection, 30 May 2017, as told to Mike Davey via the phone. Notes in the possession of Mike Davey.

- ↑ "The Courier-Journal". Louisville, Kentucky. October 8, 1958. p. 3. https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/107950404/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Memorial". http://apps.westpointaog.org/Memorials/Article/11847/.

- ↑ "The San Bernardino County Sun". San Bernardino, California. May 26, 1963. p. 5. https://www.newspapers.com/newspage/54050448/.

- ↑ "Wheeler Medal". http://www.same.org/Be-Involved/Wheeler-Medal.

- ↑ Rogers, J. David "70 years of schemes to improve and enlarge the Panama Canal"

- ↑ "Gen. Noble in Vietnam Post". https://www.nytimes.com/1970/06/26/archives/gen-noble-in-vietnam-post.html.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Charles C. Noble". http://valor.militarytimes.com/recipient.php?recipientid=109815.

- ↑ "The Cornell Daily Sun". 10 April 1973. http://cdsun.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/cornell?a=d&d=CDS19730410.2.10&e=--------20--1-----all----#.

- ↑ Perkins, John. The Secret History of the American Empire: The Truth About Economic Hit Men, p. 122 [ISBN missing].

- ↑ Elkins, Ashley. "Editorial: Freedom and restraint". http://www.djournal.com/opinion/editorial-freedom-and-restraint/article_6faa7de8-c9dc-50c9-a048-f81d5d48755d.html.

- ↑ Burial Detail: Noble, Charles C (Section 7, Grave 8134-NH) – ANC Explorer

- ↑ Charles Noble – Memorial Tributes: Volume 12 – The National Academies Press. 2008. doi:10.17226/12473. ISBN 978-0-309-12639-7. https://www.nap.edu/read/12473/chapter/38#226.

|