Religion:Man of Sorrows

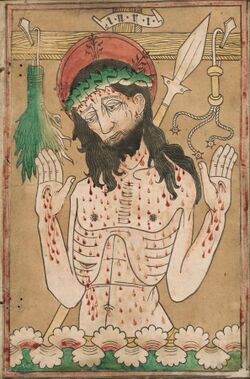

Man of Sorrows, a biblical term, is paramount among the prefigurations of the Messiah identified by the Bible in the passages of Isaiah 53 (Servant songs) in the Hebrew Bible. It is also an iconic devotional image that shows Christ, usually naked above the waist, with the wounds of his Passion prominently displayed on his hands and side (the "ostentatio vulnerum", a feature of other standard types of image), often crowned with the Crown of Thorns and sometimes attended by angels. It developed in Europe from the 13th century and was especially popular in Northern Europe.

The image continued to spread and develop iconographical complexity until well after the Renaissance, but the Man of Sorrows in its many artistic forms is the most precise visual expression of the piety of the later Middle Ages, which took its character from mystical contemplation rather than from theological speculation.[1] Together with the Pietà, it was the most popular of the Andachtsbilder-type images of the period – devotional images detached from the narrative of Christ's Passion, intended for meditation.

The Latin term Christus dolens ("suffering Christ") is sometimes used for this depiction. The Pensive Christ is a similar depiction, and the usual composition of the Mass of Saint Gregory includes a vision of the Man of Sorrows.

Biblical narrative

The phrase translated into English as "Man of Sorrows" ("אִישׁ מַכְאֹבוֹת", ’îš maḵ’ōḇōṯ in the Hebrew Bible, vir dolōrum in the Vulgate) occurs at verse 3 (in Isaiah 53):

3) He is despised and rejected of men, a Man of sorrows, and acquainted with grief. And we hid as it were our faces from Him; He was despised, and we esteemed Him not. 4) Surely He hath borne our griefs and carried our sorrows; yet we did esteem Him stricken, smitten of God, and afflicted. 5) But He was wounded for our transgressions; He was bruised for our iniquities. The chastisement of our peace was upon Him, and with His stripes we are healed.

6) All we like sheep have gone astray; we have turned every one to his own way; and the Lord hath laid on Him the iniquity of us all.[2]

Development of the image

The image developed from the Byzantine epitaphios image, which possibly dates back to the 8th century. A miraculous Byzantine mosaic icon of it is known as the Imago Pietatis or Christ of Pity. The work appears to have been brought to the major pilgrimage church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme in Rome in the 12th century. Only replicas of the original work now survive. By the 13th century it was becoming common in the West as a devotional image for contemplation, in sculpture, painting and manuscripts. It continued to grow in popularity, helped by the Jubilee Year of 1350, when the Roman image seems to have had, perhaps initially only for the Jubilee, a papal indulgence of 14,000 years granted for prayers said in its presence.[3]

The image formed part of the subject of the Mass of Saint Gregory; by 1350 the Roman icon was being claimed as a contemporary representation of the vision.[5] In this image the figure of Christ was typical of the Byzantine forerunners of the Man of Sorrows, at half length, with crossed hands and head slumped sideways to the viewer's left.

The various versions of the Man of Sorrows image all show a Christ with the wounds of the Crucifixion, including the spear-wound. Especially in Germany, Christ's eyes are usually open and look out at the viewer; in Italy the closed eyes of the Byzantine epitaphios image, originally intended to show a dead Christ, remained for longer. For some the image represented the two natures of Christ – he was dead as a man, but alive as God.[6] Full-length figures also first appear in southern Germany in wall-paintings in the 13th century, and in sculpture from the beginning of the 14th.[7]

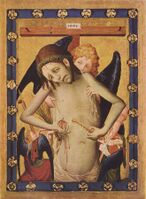

Other elements that were sometimes included, in distinct sub-forms of the image, included the Arma Christi or "Instruments of the Passion", the cross, a chalice into which blood poured from Christ's side or other wounds (giving an emphasis on the Eucharist), angels to hold these objects or support a slumped Christ himself (Meister Francke shows both roles below), and mourners or worshippers.[8] The Throne of Mercy is an image of the Trinity with Christ, often diminutive, as Man of Sorrows, supported by his Father.

Isaiah 53:2 had already been crucial in developing the iconography of the Tree of Jesse: "For He shall grow up before Him as a tender plant, and as a root out of a dry ground".

Artworks with articles

- Man of Sorrows (Geertgen tot Sint Jans), c. 1485–1495, now Utrecht

- Man of Sorrows (Maarten van Heemskerck), 1532

- The Man of Sorrows from the New Town Hall in Prague, wood sculpture, c. 1410

- Triptych of the Madonna, Giovanni Bellini and others, 1464–1470, now Venice

- The Man of Sorrows, James Ensor

Gallery

- Man of Sorrows

Master Francke: Man of Sorrows, with the Arma Christi and Angels, ca. 1430, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig

See also

- Messiah (Handel), which sets a version of the passage from Isaiah

Notes

- ↑ Schiller, quote from p. 198, figs. 681–812

- ↑ "21st Century King James Version". Biblegateway.com. http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?book_id=29&chapter=53&version=48. Retrieved 2014-04-22.

- ↑ Schiller, 199–200, also see Parshall, 58 and Pattison, 150.

- ↑ Discussed by Snyder, 176–78

- ↑ Parshall, 58. For a somewhat different chronology, see Pattison, 150

- ↑ Schiller, 198

- ↑ Schiller, 201–202

- ↑ Schiller, 201–219

References

- Ballester, Jordi (2018). "Trumpets, Heralds and Minstrels: Their Relation to the Image of Power and Representation in the Fourteenth- and Fifteenth-Century Catalano-Aragonese Painting". Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography 43 (1–2): 5–19. ISSN 1522-7464.

- Parshall, Peter, in David Landau & Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print, Yale, 1996, ISBN:0-300-06883-2

- Pattison George, in W. J. Hankey, Douglas Hedley (eds), Deconstructing radical orthodoxy: postmodern theology, rhetoric, and truth, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2005, ISBN:0-7546-5398-6, ISBN:978-0-7546-5398-1. Google books

- G. Schiller, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972 (English translation from German), Lund Humphries, London, figs. 471–75, ISBN:0-85331-324-5

- Snyder, James; Northern Renaissance Art, 1985, Harry N. Abrams, ISBN:0-13-623596-4

|