Religion:Groac'h

"La Groac'h de l'île du Lok" after Théophile Busnel, for Contes et légendes de Basse-Bretagne (1891) | |

| Grouping | Legendary creature |

|---|---|

| Sub grouping | Fairy |

| Similar entities | Witch, ogre |

| Folklore | Folklore |

| Country | Brittany |

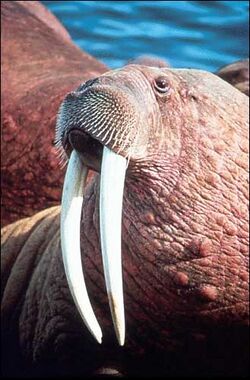

A groac'h (Breton for "fairy", "witch" or "crone", pl. groagez) is a kind of Breton water-fairy. Seen in various forms, often by night, many are old, similar to ogres and witches, sometimes with walrus teeth. Supposed to live in caverns, under the beach and under the sea, the groac'h has power over the forces of nature and can change its shape. It is mainly known as a malevolent figure, largely because of Émile Souvestre's story La Groac'h de l'île du Lok, in which the fairy seduces men, changes them into fish and serves them as meals to her guests, on one of the Glénan Islands. Other tales present them as old solitary fairies who can overwhelm with gifts the humans who visit them.

Several place-names of Lower Brittany are connected with the groac'h, especially the names of some megaliths in Côtes-d'Armor, as well as the island of Groix in Morbihan and the lighthouse of La Vieille. The origin of those fairies that belong to the archetype of "the crone" is to be found in the ancient female divinities demonized by Christianity. The influence of Breton writers in the 19th century brought them closer to the classical fairy figure. The groac'h has several times appeared in recent literary works, such as Nicolas Bréhal's La Pâleur et le Sang (1983).

Etymology

According to Philippe Le Stum, originally groac'h seems to have been the Breton word for fairies in general. It evolved to mean an old creature of deceptive beauty.[1] It is often spelled "groah", the final consonant being pronounced like the German ch.[2] One of the possible plurals is groagez.[3] According to Joseph Rio the assimilation of the groac'h with the fairy is more the result of the influence of Émile Souvestre's tale, and commentaries on it, than a belief deriving from the popular traditions of Lower Brittany: "The Groac'h of Lok Island", a story intended for literate audiences, uses a writing technique based on the interchangeable use of the words "fairy" and "groac'h".[4] Anatole Le Braz comments on this name that "Groac'h is used in good and bad senses by turns. It can mean an old witch or simply an old woman."[5]

Characteristics

The groagez are the fairies most often encountered in Brittany,[2] generally in forests and near springs:[6] they are essentially the fairies of Breton wells.[7] Likewise, a certain number of "sea fairies" bear the name of groac'h,[3] sometimes interchangeably with those of "morgen" or "siren".[8] Joseph Mahé (fr) speaks (1825) of a malicious creature that he was frightened of as a child, reputed to inhabit wells in which it drowned those children that fell in.[9] It is possible that Souvestre drew the evil characteristics of "his" groac'h from Mahé,[10] and indeed he admits in his notes a certain reinvention of tradition.[11]

Appearance

Because of their multiform character, the groagez are hard to define.[12] One of them is said to frequent the neighborhood of Kerodi, but the descriptions vary: an old woman bent and leaning on a crutch, or a richly dressed princess, accompanied by korrigans.[13] Often the descriptions insist on its likeness to an old woman; Françoise Morvan mentions the name "beetle-fairy".[14] She notes cases where the groagez have exceptionally long "walrus" teeth, which may be the length of a finger or may even drag along the ground, though in other cases they have no such teeth, or at any rate nothing is said of them. Sometimes they are hunchbacked.[2] The storyteller Pierre Dubois describes them as shapeshifters capable of taking on the most flattering or the most repugnant appearance: swans or wrinkled, peering hobgoblins. He attributes green teeth to them, or more rarely red, as well as "a coat of scales".[15] For Morvan, the variety of these descriptions is a result of two phenomena. On the one hand, it is possible that these fairies change their appearance as they age, to become like warty frogs. On the other hand, a Russian tradition reported by Andrei Sinyavsky has the fairies go through cycles of rejuvenation and ageing according to the cycles of the moon: a similar tradition may have existed in Brittany.[12]

Attributes and character

Pierre Dubois compares the groac'h to an ogress or a "water-witch".[15] André-François Ruaud (fr) relates it rather to undines,[16] Richard Ely and Amélie Tsaag Valren to witches,[17] Édouard Brasey describes it as a "lake fairy".[18] Be that as it may, the groac'h is one of the most powerful fairies in Breton waters.[19] In its aquatic habitat, as on land, it has power over the elements.[20] The groac'h of Lanascol Castle could shake the dead autumn leaves and turn them to gold, or bend the trees and make the ponds ripple as it passed.[13] Although it is mostly known by negative representations, the groac'h is not necessarily bad. It may politely receive humans in its lair and offer treasure, magical objects (most often in threes), and cures. Like many other fairies, it also takes care of laundry[6] and spinning.[21] They are overbearing, but generally full of good intentions. Most often, the groagez are described as being solitary in their retreats under the sea, in a rock or in the sands,[3] but some stories tell of an entirely female family life. They do not abandon their children or leave changelings.[22] Sometimes they are accompanied by a green water horse and a pikeman.[23] They are more inconstant and more sensitive than other Breton fairies, taking offence easily.[23] In Finistère, groagez reveal to miners the existence of silver-bearing lead.[24]

Stories and collected legends

Several collections report a groac'h in one or another place in Brittany. Souvestre evokes one of these fairies, likened to a naiad, in a well in Vannes:[10][20] this legend seems to have been quite popular in its day, and could have the same sources as the tale of the fairy of the well.[25] It belongs to the theme of "spinners by the fountain" in the Aarne-Thompson classification.[26] A story collected by Anatole Le Braz makes one of these fairies the personification of the plague: an old man from Plestin finds a groac'h who asks for his help in crossing a river. He carries it, but it becomes more and more heavy, so that he sets it back down it where he found it, thereby preventing an epidemic of plague in the Lannion district.[27] François-Marie Luzel also brings together several traditions around the groagez, that people would shun them as they would Ankou. Some are known to have the power of changing into foals, or again to haunt the forest of Coat-ann-noz (the wood of the night).[28] The duke's pond in Vannes would house a groac'h, a former princess who threw herself into the water to flee a too importunate lover, and who would sometimes be seen combing her long blonde hair with a golden comb.[29]

La Groac'h de l'Île du Lok

The most famous story evoking a groac'h is La Groac'h de l'Île du Lok, collected, written and arranged by Émile Souvestre for his book Le Foyer breton (1844). Houarn Pogamm and Bellah Postik, orphan cousins, grow up together in Lannilis and fall in love, but they are poor, so Houarn leaves to seek his fortune. Bellah gives him a little bell and a knife, but keeps a third magic object for herself, a wand. Houarn arrives at Pont-Aven and hears about the groac'h of Île du Loc'h (fr), a fairy who inhabits a lake on the largest of the Glénan Islands, reputed to be as rich as all the kings on earth put together. Houarn goes to the island of Lok and gets into an enchanted boat in the shape of a swan, which takes him underwater to the home of the groac'h. This beautiful woman asks him what he wants, and Houarn replies that he is looking for the wherewithal to buy a little cow and a lean hog. The fairy offers him some enchanted wine to drink and asks him to marry her. He accepts, but when he sees the groac'h catch and fry fish which moan in the pan he begins to be afraid and regrets his decision. The groac'h gives him the dish of fried fish and goes away to look for wine.[30]

Houarn draws his knife, whose blade dispels enchantments. All the fish stand up and become little men. They are victims of the groac'h, who agreed to marry her before being metamorphosed and served as dinner to the other suitors. Houarn tries to escape but the groac'h comes back and throws at him the steel net she wears on her belt, which turns him into a frog. The bell that he carries on his neck rings, and Bellah hears it at Lannilis. She takes hold of her magic wand, which turns itself into a fast pony, then into a bird to cross the sea. At the top of a rock, Bellah finds a little black korandon, the groac'h's husband, and he tells her of the fairy's vulnerable point. The korandon offers Bellah men's clothes to disguise herself in. She goes to the groac'h, who is very happy to receive such a beautiful boy and yields to the request of Bellah, who would like to catch her fish with the steel net. Bellah throws the net on the fairy, cursing her thus: "Become in body what you are in heart!". The groac'h changes into a hideous creature, the queen of mushrooms, and is thrown into a well. The metamorphosed men and the korandon are saved, and Bellah and Houarn take the treasures of the fairy, marry and live happily ever after.[30]

For the scholar Joseph Rio this tale is important documentary evidence on the character of the groac'h.[10] Souvestre explained why he chose to place it on the island of Lok by the multiplicity of versions of the storytellers which do so.[31] La Groac'h de l'île du Lok was even more of a success in Germany than it had been in Brittany. Heinrich Bode published it under the title of Die Wasserhexe in 1847,[32] and it was republished in 1989 and 1993.[33] The story was likewise translated into English (The Groac'h of the Isle) and published in The Lilac Fairy Book in 1910.[34] Between 1880 and 1920 it served as study material for British students learning French.[35]

The Groac'h of the Spring

This tale, collected by Joseph Frison around 1914, tells of a young girl who goes one night to a spring to help her mother. She discovers that a groac'h lives there. The fairy tells her never to come back by night, otherwise she will never see her mother again. The mother falls ill, and the girl returns to draw some water in the night in spite of the prohibition. The groac'h catches the girl and keeps her in its cave, which has every possible comfort. Although she is separated from her family the girl is happy there. A young groac'h comes to guard her while the groac'h of the spring is away visiting one of its sisters. She dies while with her sister, having first sent a message to the young groac'h: the girl is free to leave if she wishes. Knowing that the home of the groac'h is much more comfortable than her own, the girl asks for a key so that she can enter or leave at her own convenience. The young groac'h has her wait for one month, while the elder sister dies. She then gives her two keys, with instructions never to stay outside after sunset. The little girl meets one of her family while out walking, but resolves to return early to keep her promise. Later she meets a very handsome young man, whom she leaves, promising to come back the next day. The groac'h advises her to marry him, assuring her that this will lift the prohibition on her returning after sunset. She follows this advice and lives happily ever after with her new husband.[36]

The Fairy of the Well / Groac'h ar puñs

According to this recent story (collected by Théophile Le Graët in 1975), a widower with a daughter marries a black-skinned woman who has a daughter, also black. The new bride treats her stepdaughter very badly, and demands she spin all day long. One day, when near a well, the girl encounters an old walrus-toothed fairy who offers her new clothes, heals her fingers, goes to her place and offers to share its house with her. She eagerly moves in and is very happy there. When eventually she announces that she wants to leave, the fairy gives her a magic stone. She goes back to her stepmother's home where, with her new clothes, no-one recognizes her. With the fairy stone she can get everything she wants. The black girl becomes jealous and throws herself down the well in the hope of getting the same gifts, but the fairy only gives her a thistle. The black girl wishes for the greatest prince in the world to appear so that he can ask for her hand in marriage, but it is the Devil who appears and carries her away. In the end the good girl returns to her home in the well, and sometimes she can be heard singing.[37]

The Sea Fairies / Groac'had vor

This tale takes place on the island of Groagez (the "island of women" or the "fairy island"), which Paul Sébillot describes as being the home of an old woman who is a spinner and a witch; it is in Trégor, one kilometer from Port-Blanc.[19]

According to this tale, collected by G. Le Calvez at the end of the 19th century, a vor Groac'h, "sea fairy",[38] lives in a hollow rock on the island. A woman happens to pass by, and comes across the old fairy spinning with her distaff. The groac'h invites the woman to approach it and gives her its distaff, instructing her that it will bring her her fortune, but that she must tell no-one about it. The woman goes home and quickly becomes rich thanks to the distaff, the thread of which never runs out and is much finer in quality than all others. But the temptation to speak about it becomes too great for her. The moment she reveals that the distaff comes from a fairy all the money she has earned from it disappears.[39]

The Fairy / Groac'h

This story was collected by Anatole Le Braz, who makes reference to the belief in fairies among people of his acquaintance living near his friend Walter Evans-Wentz. A ruined manor house called Lanascol Castle is said to have housed a fairy known as Lanascol groac'h. One day, the landowners put up for sale a part of the estate where they no longer live. A notary from Plouaret conducts the auction, during which prices go up very high. Suddenly, a gentle yet imperious female voice makes a bid raising the price by a thousand francs. All the attendants look to see who spoke, but there is no woman in the room. The notary then asks loudly who bid, and the female voice answers groac'h Lanascol!. Everyone flees. Since then, according to Le Braz, the estate has never found a buyer.[40]

Localities, place-names and religious practices

Many place-names in Lower Brittany are attributed to a groac'h. The Grand Menhir, called Men Er Groah, at Locmariaquer probably owes its name to an amalgamation of the Breton word for "cave", groh, with the word groac'h.[41] Pierre Saintyves cites from the same commune a "table of the old woman", a dolmen called daul ar groac'h.[42] At Maël-Pestivien three stones two meters high placed next to each other in the village of Kermorvan, are known by the name of Ty-ar-Groac'h, or "the house of the fairy".[43]

In 1868, an eight-meter menhir called Min-ar-Groach was destroyed in Plourac'h.[44] In Cavan, the tomb of the "groac'h Ahès", or "Be Ar Groac'h", has become attributed not to the groac'h but to the giant Ahès (fr).[45] There is a Tombeau de la Groac'h Rouge (Tomb of the Red Groac'h) in Prat, attributed to a "red fairy" that brought the stones in her apron.[46] This megalith is however almost destroyed.[47] According to Souvestre and the Celtomaniac Alfred Fouquet (fr) (1853), the island of Groix got its name (in Breton) from the groagez, described by them as "druidesses" now seen as old women or witches.[48] For the writer Claire de Marnier this tradition, which makes the islanders sons of witches, is a "remarkable belief" peculiar to "the Breton soul".[49][50]

The rock of Croac'h Coz, or "the island of the old fairy", in the commune of Plougrescant, was the home of an old groac'h who would engage in spinning from time to time. Sébillot relates that the fishermen of Loguivy (in Ploubazlanec) once feared to pass near the cave named Toul ar Groac'h, "fairy hole", and preferred to spend the night under their beached boats until the next tide, rather than risk angering the fairy.[51] Similarly, Anatole Le Braz cites Barr-ann-Heol near Penvénan, as a dangerous place where a groac'h keeps watch, ready to seize benighted travellers at a crossroads.[52] In Ushant many place-names refer to it, including the Pointe de la Groac'h and the lighthouse of La Vieille, in reference, according to Georges Guénin, to "a kind of witch".[53]

Some traces of possible religious invocation of these fairies are known. Paul-Yves Sébillot (fr) says that the sick once came to rub the pre-Christian statue called Groac'h er goard (or Groac'h ar Goard ) so as to be healed.[54][55] The seven-foot-tall granite statue known as the Venus of Quinipily represents a naked woman of "indecent form"[56] and could be a remnant of the worship of Venus or Isis.

Analysis

According to Marc Gontard, the groac'h demonstrates the demonization of ancient goddesses under the influence of Christianity: it was changed to a witch just as other divinities became lost girls and mermaids.[57] Its palace under the waves is a typical motif of fairy tales and folk-stories, which is also found in, for example, the texts of the Arthurian legend, Irish folklore and several Hispanic tales.[58] Pierre Dubois likens the groac'h to many maleficent water-fairies, like Peg Powler, Jenny Greenteeth, the mère Engueule and the green ogresses of Cosges, who drag people underwater to devour them.[59] Joseph Rio included it in a global evolution of Breton fairies between 1820 and 1850, so that from small, dark-skinned, wrinkled creatures close to the korrigans, in the texts of the scholars of the time they more and more often become pretty women of normal size, probably to compete with the Germanic fairies.[60]

The groac'h has been likened to the enigmatic and archetypal character of "the Crone", studied by various folklorists. This name, in French la Vieille, is often applied to megaliths.[61] Edain McCoy equates the groac'h with la Vieille, citing especially the regular translation of the word as "witch". She adds that several Breton tales present this creature in a negative way, while none draw a flattering portrait.[62]

In literature

A groac'h appears in the novel La Pâleur et le Sang published by Nicolas Bréhal in 1983. This horrible witch, feared by the fishermen, lays a curse on the Bowley family.[63] A "mystical and fantastic" novel,[64] La Pâleur et le Sang includes the groac'h among the mysterious and almost diabolical forces that assail the island of Vindilis. This old woman is portrayed as having "magical and evil powers", and as threatening with reprisals those characters who offend her. Her murder is one of the causes of the misfortunes that hit the island.[64] A groac'h also appears in Absinthes & Démons, a collection of short stories by Amber Dubois published in 2012.[65] In Jean Teulé's novel Fleur de tonnerre (2013), groac'h is a nickname given to Hélène Jégado when she is a little girl, in Plouhinec.[66]

References

- ↑ Le Stum 2003, p. 7

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Morvan 1999, p. 73

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Morvan 1999, p. 196

- ↑ Rio 2006, p. 251

- ↑ Le Braz, Anatole; Dottin, Georges (1902) (in fr). La légende de la mort chez les Bretons armoricains. 2. Paris: Honoré Champion. p. 179.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Morvan 1999, p. 74

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 99

- ↑ Mozzani 2015, chap. "Vannes"

- ↑ Mahé, Joseph (1825) (in fr). Essai sur les antiquités du département du Morbihan. Vannes: Galles Ainé. p. 417.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Rio 2006, p. 250

- ↑ Souvestre 1845, p. 156

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Morvan 1999, p. 144

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Giraudon, Daniel (2005). "Penanger et de La Lande, Gwerz tragique au XVIIe siècle en Trégor" (in fr). Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest 112 (4): 7. doi:10.4000/abpo.1040. https://journals.openedition.org/abpo/1040. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 79

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Dubois 2008, p. 108

- ↑ Ruaud 2010

- ↑ Ely & Tsaag Valren 2013, p. 151

- ↑ Brasey, Édouard (1999) (in fr). Sirènes et ondines. Paris: Pygmalion. p. 195. ISBN 9782857046080.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Le Stum 2003, p. 21

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Chesnel de la Charbouclais, Louis Pierre François Adolphe, marquis de (1856) (in fr). Dictionnaire des superstitions, erreurs, préjugés et traditions populaires: où sont exposées le croyances superstitieuses des temps anciens et modernes.... Paris: J.-P. Migne. p. 442. https://books.google.com/books?id=GgQ2AQAAMAAJ&pg=PT173. Retrieved 5 September 2018.

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 202

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 77

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Morvan 1999, p. 78

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1894) (in fr). Les travaux publics et les mines dans les traditions et les superstitions de tous les pays: les routes, les ponts, les chemins de fer, les digues, les canaux, l'hydraulique, les ports, les phares, les mines et les mineurs. Paris: J. Rothschild. p. 410.

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 106

- ↑ Morvan 1999, p. 107

- ↑ Le Braz, Anatole (2011). "Celui qui porta la peste sur les épaules" (in fr). La légende de la mort. Paris: Archipoche. ISBN 9782352872818.

- ↑ Morvan, Françoise, ed (1995) (in fr). Nouvelles veillées bretonnes. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. pp. 74, 83–84. ISBN 9782868471697.

- ↑ (in fr) Pèlerinages de Bretagne (Morbihan). Paris: A. Bray. 1855. pp. 157–158. https://books.google.com/books?id=ymQqAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA157.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Souvestre 1891

- ↑ "La Groac'h de l'Île du Lok" (in fr). Revue des traditions populaires (Librairie orientale et américaine) 7: 441–442. 1892.

- ↑ Blanchard, Nelly "Le succès d’Émile Souvestre dans le monde germanophone", in Plötner-Le Lay & Blanchard 2006, pp. 248–253

- ↑ Blanchard, Nelly "Le succès d’Émile Souvestre dans le monde germanophone", in Plötner-Le Lay & Blanchard 2006, p. 262

- ↑ The Lilac Fairy Book. London: Longmans, Green. 1910. http://www.online-literature.com/andrew_lang/lilac_fairy/28/.

- ↑ Le Disez, Jean-Yves "Souvestre tel qu’il sera en anglais, ou la prolifération métatextuelle de l’œuvre dans le monde anglophone", in Plötner-Le Lay & Blanchard 2006, p. 218

- ↑ Frison, Joseph (1914). "La groac'h de la fontaine" (in fr). Revue des traditions populaires: 54–56.

- ↑ Théophile Le Graët, 1975. Cited by Morvan 1999, pp. 100–106

- ↑ Mozzani 2015, chapter, "Penvénan (Port-Blanc)"

- ↑ Le Calvez, G. (1897). "Groac'had vor" (in fr). Revue des traditions populaires 12: 391.

- ↑ The Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries: The Classic Study of Leprechauns, Pixies, and Other Fairy Spirits. London: Henry Frowde. 1911. pp. 185–188. ISBN 9781148927992. https://books.google.com/books?id=oOfuAgAAQBAJ&q=%22female+voice+very+gentle%22&pg=PA187. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- ↑ Le Roux, Charles-Tanguy (2006) (in fr). Monuments mégalithiques à Locmariaquer (Morbihan): Le long tumulus d'Er Groah dans son environnement. Paris: CNRS Editions. p. 35. ISBN 9782271064905.

- ↑ Saintyves 1934, p. 481

- ↑ Sébillot, Paul (1983) (in fr). Le folklore de France: La terre et le monde souterrain. 2. Paris: Éditions Imago. p. 152. ISBN 9782902702114.

- ↑ Harmoi, A-L (1911) (in fr). Inventaire des découvertes archéologiques du département des Côtes-du-Nord. XVIII. St Brieuc: Société d'émulation des Côtes-du-Nord – Impr. Guyon. http://callac.joseph.lohou.fr/archeoplourach.html. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ Saintyves 1934, p. 390

- ↑ Billington, Sandra; Aldhouse-Green, Miranda Jane (1996). The Concept of the Goddess. New York: Psychology Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780415144216.

- ↑ Guénin, Georges (1995) (in fr). Le légendaire préhistorique de Bretagne: les mégalithes, traditions et légendes. Rennes: La Découvrance. p. 90. ISBN 9782910452384.

- ↑ Fouquet, Alfred (1853) (in fr). Des monuments celtiques et des ruines romaines dans le Morbihan. Vannes: A. Cauderan. p. 34. https://archive.org/details/desmonumentscel00fouqgoog. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ↑ de Marmier, Claire (1947) (in fr). La mystique des eaux sacrées dans l'antique Armor: essai sur la conscience mythique. Bibliothèque des textes philosophiques. Paris: Vrin. p. 235. ISBN 9782711605507.

- ↑ This etymology connecting Groix and the groac'h is only one possibility among several others. See Frédéric Le Tallec, "À propos de l'étymologie de Groix" in La Chaloupe de l'île, the journal of the island of Groix, 1984.

- ↑ Mozzani 2015, p. Entrée "Loguivy-de-la-Mer"

- ↑ Le Braz 2011, chapter, "La 'pipée' de Jozon Briand"

- ↑ Georges Guénin (1995) (in fr). Le légendaire préhistorique de Bretagne: les mégalithes, traditions et légendes. Amateur averti. Rennes: La Découvrance. p. 33. ISBN 9782910452384.

- ↑ Richard, Louis (1969). "Recherches récentes sur le culte d'Isis en Bretagne" (in fr). Revue de l'histoire des religions 176 (2): 126. doi:10.3406/rhr.1969.9580.

- ↑ Bizeul, Louis Jacques Marie (1843). "Mémoire sur les voies romaines de la Bretagne; et en particulier celles du Morbihan" (in fr). Bulletin Monumental 9: 241.

- ↑ Bizeul, Louis Jacques Marie (1843) (in fr). Mémoire sur les voies romaines de la Bretagne, et en particulier de celles du Morbihan. Caen: Chalopin. p. 82.

- ↑ Gontard, Marc (2008). "Le récit oral dans la culture populaire bretonne" (in fr). La Langue muette: Littérature bretonne de langue française. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes. ISBN 9782753506145.

- ↑ Krappe, Alexander Haggerty (1933). "Le Lac enchanté dans le Chevalier Cifar" (in fr). Bulletin Hispanique 35 (2): 113. http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/article/hispa_0007-4640_1933_num_35_2_2575?_Prescripts_Search_tabs1=standard&. Retrieved 16 March 2015.

- ↑ Dubois 2008, p. 109

- ↑ Rio 2006, pp. 151–152

- ↑ Soutou, A. (September 1954). "Toponymie, folklore et préhistoire: Vieille Morte" (in fr). Revue internationale d'onomastique 6 (3): 183–189. doi:10.3406/rio.1954.1425.

- ↑ McCoy, Edain (1998). Celtic Women's Spirituality: Accessing the Cauldron of Life. St Paul, Minn.: Llewellyn Worldwide. p. 103. ISBN 9781567186727.

- ↑ Bréhal, Nicolas (1988) (in fr). La Pâleur et le Sang. Paris: Mercure de France. ISBN 9782070380725.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Bond, David J. (1994). "Nicolas Brehal: Writing as Self-Preservation". LitteRealite. http://pi.library.yorku.ca/ojs/index.php/litte/article/download/26798/24784. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ↑ Dubois, Ambre (2012) (in fr). Absinthes & Démons. Logonna-Daoulas: Éditions du Riez. ISBN 9782918719434. https://books.google.com/books?id=IXiJAQAAQBAJ&pg=PT37. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

- ↑ Teulé, Jean (2013) (in fr). Fleur de tonnerre. Paris: Éditions Julliard. ISBN 9782260020585. https://books.google.com/books?id=jq9VLHzdG78C&q=%22silhouette+de+sa+fille+sur+le+seuil%22&pg=PT8. Retrieved 20 October 2018.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Saintyves, Pierre (1934) (in fr). Corpus du folklore préhistorique en France et dans les colonies françaises. 3. Paris: E. Nourry.

- Souvestre, Émile (1845). "La Groac’h de l’Île du Lok" (in fr). Le foyer breton: Traditions populaires. Paris: Coquebert. pp. 76–89. https://books.google.com/books?id=Lks6AAAAcAAJ. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- Souvestre, Émile (1891). "La Groac’h de l’Île du Lok" (in fr). Contes et légendes de Basse-Bretagne. Nantes: Société des bibliophiles bretons. https://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Livre:Souvestre,_Laurens_de_la_Barre,_Luzel_-_Contes_et_l%C3%A9gendes_de_Basse-Bretagne.djvu. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

Secondary sources

- Dubois, Pierre (2008). "La Groac'h" (in fr). La Grande Encyclopédie des fées. Paris: Hoëbeke. ISBN 9782842303266.

- Ely, Richard; Tsaag Valren, Amélie (2013). "Groac'h" (in fr). Bestiaire fantastique & créatures féeriques de France. Terre de Brume. p. 151. ISBN 9782843625084.

- Le Stum, Philippe (2003) (in fr). Fées, Korrigans & autres créatures fantastiques de Bretagne. Rennes: Ouest-France. ISBN 978-2737323690.

- Morvan, Françoise (1999) (in fr). La douce vie des fées des eaux. Arles: Actes Sud. ISBN 9782742724062.

- Mozzani, Éloïse (2015) (in fr). Légendes et mystères des régions de France. Paris: Robert Laffont. ISBN 9782221159224.

- Plötner-Le Lay, Bärbel; Blanchard, Nelly (2006) (in fr). Émile Souvestre, écrivain breton porté par l'utopie sociale. Morlaix: Centre de Recherche Bretonne et Celtique; LIRE (Université Lyon 2).

- Rio, Joseph (2006). "Du korrigan à la fée celtique" (in fr). Littératures de Bretagne: mélanges offerts à Yann-Ber Piriou. Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes. pp. 237–252. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00453435/. Retrieved 27 October 2018. The book attributed this article to Gaël Milin, but Presses Universitaires de Rennes corrected the mistake in an errata.

- Ruaud, André-François (2010). "Groac'h". Le Dico féérique: Le Règne humanoïde. Bibliothèque des miroirs. Bordeaux: Les moutons électriques. ISBN 9782361830304.

External links

|