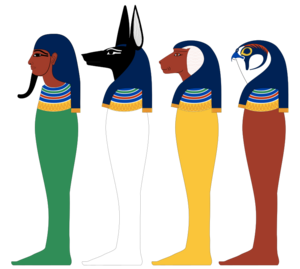

Religion:Four sons of Horus

The four sons of Horus were a group of four gods in Egyptian religion, who were essentially the personifications of the four canopic jars, which accompanied mummified bodies.[1] Since the heart was thought to embody the soul, it was left inside the body.[2] The brain was thought only to be the origin of mucus, so it was reduced to liquid, removed with metal hooks, and discarded.[3] This left the stomach (and small intestines), liver, large intestines, and lungs, which were removed, embalmed and stored, each organ in its own jar. There were times when embalmers deviated from this scheme: during the 21st Dynasty they embalmed and wrapped the viscera and returned them to the body, while the Canopic jars remained empty symbols.[1]

The earliest reference to the sons of Horus the Elder is found in the Pyramid Texts[4] where they are described as friends of the king, as they assist the king in his ascension to heaven in the eastern sky by means of ladders.[citation needed] Their association with Horus the Elder specifically goes back to the Old Kingdom when they were said not only to be his children but also his souls. As the king, or Pharaoh was seen as a manifestation of, or especially protected by, Horus, these parts of the deceased pharaoh, referred to as the Osiris, were seen as parts of Horus, or rather, his children,[5] an association that did not diminish with each successive pharaoh.

Since Horus was their father, so Isis, Horus's original wife in the early mythological phase, was usually seen as their mother, although Hathor was also believed to be their mother,[6] though in the details of the funerary ritual each son, and therefore each canopic jar, was protected by a particular goddess. Others say their mother was Serket, goddess of medicine and magic. Just as the sons of Horus protected the contents of a canopic jar, the king's organs, so they in turn were protected. As they were male in accordance with the principles of male/female duality their protectors were female.

- Imsety – human form – direction South – protected the liver – protected by Isis.

- Duamutef – jackal form – direction East – protected the stomach – protected by Neith.

- Hapi – baboon form – direction North – protected the lungs – protected by Nephthys.

- Qebehsenuef – hawk form – direction West – protected the intestines – protected by his mother Serket.[7][8]

The classic depiction of the four sons of Horus on Middle Kingdom coffins show Imsety and Duamutef on the eastern side of the coffin and Hapi and Qebehsenuef on the western side. The eastern side is decorated with a pair of eyes and the mummy was turned on its side to face the east and the rising sun; therefore, this side is sometimes referred to as the front. The sons of Horus also became associated with the cardinal compass points, so that Hapi was the north, Imsety the south, Duamutef the east and Qebehsenuef the west.[9] Their brother was Ihy, son of Hathor.

Until the end of the 18th Dynasty the canopic jars had the head of the king, but later they were shown with animal heads.[2] Inscriptions on coffins and sarcophagi from earliest times showed them usually in animal form.

Hapi

| <hiero>H-Aa5:p-i-i</hiero> |

| Hapi in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Hapi (xapi) the baboon headed son of Horus protected the lungs of the deceased and was in turn protected by the goddess Nephthys.[10] The spelling of his name includes a hieroglyph which is thought to be connected with steering a boat, although its exact nature is not known. For this reason he was sometimes connected with navigation, although early references call him the great runner: "You are the great runner; come, that you may join up my father N and not be far in this your name of Hapi, for you are the greatest of my children – so says Horus"[11]

In Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead Hapi is given the following words to say: "I have come to be your protection. I have bound your head and your limbs for you. I have smitten your enemies beneath you for you, and given you your head, eternally."[12]

Spell 148 in the Book of the Dead directly associates all four of Horus's sons, described as the four pillars of Shu and one of the four rudders of heaven, with the four cardinal points of the compass. Hapi was associated with the north.[13]

Imsety

| <hiero>i-im:z-ti-i</hiero> |

| Imsety in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Imsety the human headed son of Horus, protected the liver of the deceased and was in turn protected by the goddess Isis.[10] It seems that his role was to help revivify the corpse of the dead person, as he is asked to lift them up by Horus: "You have come to N; betake yourself beneath him and lift him up, do not be far from him, (even) N, in your name of Imsety."[11]

To stand up meant to be active and thus alive while to be prone signified death. In Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead Imsety is given the following words to say: "I am your son, Osiris, I have come to be your protection. I have strengthened your house enduringly. As Ptah decreed in accordance with what Ra himself decrees."[12] Again the theme of making alive and revivifying is alluded to through the metaphor of making his house flourish. He does this with the authority of two creator gods Ptah and Ra (or Re).

Spell 148 in the Book of the Dead directly associates all four of Horus's sons to the four cardinal points. Imsety was associated with the south.[13]

Duamutef

| <hiero>N14-G14-t:f-or-N14:D37-t:f</hiero> |

| Duamutef in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Duamutef, the jackal-headed son of Horus, protected the stomach of the deceased and was in turn protected by the goddess Neith.[10] It seems that his role was to worship the dead person, and his name means literally "he who worships his mother". In the Coffin Texts Horus calls upon him, "Come and worship my father N for me, just as you went that you might worship my mother Isis in your name Duamutef."[11]

Isis had a dual role. Not only was she the wife of Osiris and the mother of Horus, but she was also the consort of Horus the Elder and thus the mother of the sons of Horus. This ambiguity is added to when Duamutef calls Osiris, rather than Horus his father, although kinship terms were used very loosely, and "father" can be used as "ancestor" and "son" as "descendant".[14] In Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead Duamutef is given the following words to say: "I have come to rescue my father Osiris from his assailant ."[12]

The text does not make it clear who might assail Osiris, although there are two major candidates. The obvious one is Set, the murderer of Osiris.[15] Somehow the son who worships his mother Isis is able to assist in overcoming Set. The other possibility is Apophis, the serpent demon who prevents the Sun's passage and thus the resurrection of Osiris.[16] Either way, Duamutef through his worship of Isis has the power to protect the deceased from harm.

Duamutef was also considered one of the four pillars of Shu, a rudder of heaven, and was associated with the east.[13]

Qebehsenuef

| <hiero>W15-sn-sn-sn-f</hiero> |

| Qebehsenuef in hieroglyphs |

|---|

Qebehsenuef was the falcon-headed son of Horus, and protected the intestines of the deceased. He was in turn protected by the goddess Serket.[10] It appears that his role was to refresh the dead person, and his name means literally "he who libates his siblings". Horus commands him, "Come refresh my father; betake yourself to him in your name of Qebehsenuef. You have come that you may make coolness for him after you ... "[11]

Libation or showering with cool water was a traditional form of worship in Ancient Egypt. There are many images of the pharaoh presenting libation to the gods. There is a sense of a dual function of cleansing and refreshing them.

After Set murdered Osiris he cut the body into pieces and scattered them around the Delta.[15] This was anathema to the Egyptians and the service that Qebehsenuef gives to the dead is to reassemble their parts so they can be properly preserved. In Spell 151 of the Book of the Dead he is given the following words to say: "I am your son, Osiris, I have come to be your protection. I have united your bones for you, I have assembled your limbs for you. have brought you your heart, and placed it for you at its place in your body."[12]

Qebehsenuef was the god associated with the west.[13]

Baboon, Jackal, Falcon and Human

The reasons for attributing these four animals to the sons of Horus is not known, although we may point to other associations which these animals have in Egyptian mythology. The baboon is associated with the moon and Thoth, the god of wisdom and knowledge, and also the baboons which chatter when the sun rises raising their hands as if in worship.[17] The jackal (or possibly dog) is linked to Anubis and the act of embalming and also Wepwawet the "opener of the ways" who seeks out the paths of the dead.[18] The hawk is associated with Horus himself and also Seker the mummified necropolis god. Imseti, the human, may be linked to Osiris himself or Onuris the hunter.[19]

The Egyptians themselves linked them with the ancient kings of Lower and Upper Egypt, the Souls of Pe and Nekhen. In Spells 112 and 113 of the Book of the Dead which have their origins in the earlier Coffin Texts Spells 157 and 158, it is described how Horus has his eye injured, and because of this is given the sons of Horus:

As for Imsety, Hapi, Duamutef, Qebehsenuef, their father is Horus, their mother Isis. And Horus said to Ra, place two brothers in Pe, two brothers in Nekhen from this my troupe, and to be with me assigned for eternity. The land may flourish, the turmoil be quenched. It happened for Horus who is upon his papyrus-column. I know the powers of Pe; it is Horus, it is Imsety, it is Hapy.[20]

The injury of Horus's eye is part of the myth cycle known as the Contending of Horus and Set recounting how they fought over the crown of Egypt.[21]

In a unique illustration in the tomb of Ay the sons of Horus are shown wearing the red and white crowns as the Souls of Pe and Nekhen, the souls of the royal ancestors.

The attributes of the sons of Horus are not limited to their role as the protectors of canopic jars. They appear as the four rudders of heaven in Spell 148 of the Book of the Dead, as four of the seven celestial spirits summoned by Anubis in Spell 17 of the Book of the Dead and through this are linked to the circumpolar stars of the Great Bear (or Plough): "The tribunal around Osiris is Imset, Hapi, Duamutef, Qebehsenuf, these are at the back of the Plough constellation of the northern sky."[22]

See also

- Bacab

- Four Heavenly Kings

- Guardians of the directions

- Lokapala

- Eye of Horus

- Tetramorph

- Titan (mythology)

- Anemoi

- Four Dwarves (Norse Mythology)

- Four Stags (Norse Mythology)

- Ezekiel 1, similarities to his prophetic vision

- Carl Jung Man and his Symbols, Chapter 1.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Aufderheide, p. 258

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Germer, p. 462

- ↑ Germer, pp. 460–461

- ↑ Assmann, p. 357

- ↑ Assmann, p. 467

- ↑ Griffiths, p. 49

- ↑ Aufderheider, p. 237

- ↑ Taylor, pp. 201ff

- ↑ Lurker, p. 104

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 O'Connor, p. 121

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Faulkner, pp. 520–523

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 "Book of the Dead, Chapter 151", Digital Egypt for Universities, University College, London, accessed 2 December 2011

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Budge, p. 240

- ↑ Pinch, p. 204

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Budge, p. 361

- ↑ Budge, p. 359

- ↑ Kummer, p. 4

- ↑ Malkowski and Schwaller de Lubicz, p. 305

- ↑ Hart, p. 113

- ↑ "Book of the Dead, Chapter 112", Digital Egypt for Universities, University College, London, accessed 2 December 2011

- ↑ Sellers, p. 63

- ↑ "Book of the Dead, Chapter 17", Digital Egypt for Universities, University College, London, accessed 2 December 2011

References

- Aufderheide, Arthur C. (2003). The Scientific Study of Mummies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81826-5.

- Assmann, Jan (2005). Death and Salvation in Ancient Egypt. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-4241-9.

- British Museum (1855). Synopsis of the Contents of the British Museum. London: R. & A. Taylor. OCLC 182918120.

- Budge, Sir Edward Wallis (2010) [1925]. The Mummy; a Handbook of Egyptian Funerary Archaeology. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-01825-8.

- Faulkner, Raymond Oliver (2004). The Ancient Egyptian Coffin Texts. Oxford: Aris and Phillips. ISBN 0-85668-754-5.

- Germer, Renate (1998). "Mummification". in Regine Schulz and Matthias Seidel (eds). Egypt – The World of the Pharaohs. Cologne: Könemann. ISBN 3-89508-913-3.

- Griffiths, John Gwyn (1961). The Conflict of Horus and Seth from Egyptian and Classical Sources: A Study in Ancient Mythology. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. OCLC 510538.

- Hart, George (2005). Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-34495-6.

- Kummer, Hans (1995). In Quest of the Sacred Baboon. Chichester: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-04838-X.

- Lurker, Manfred (1974) (in German). Lexikon der Götter und Symbole der alten Ägypter. Bern: Scherz. OCLC 742376579.

- Malkowski, Edward F.; R A Schwaller de Lubicz (2007). The Spiritual Technology of Ancient Egypt : Sacred Science and the Mystery of Consciousness. Rochester, Vt.: Inner Traditions. ISBN 1-59477-186-3.

- O'Connor, David (1998). Amenhotep III: Perspectives on His Reign. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10742-9.

- Pinch, Geraldine (2002). Handbook of Egyptian Mythology. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-Clio. ISBN 1-57607-242-8.

- Simpson, William Kelly, ed (1972). The Literature of Ancient Egypt. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01482-1.

- Sellers, Jane B. The Death of Gods in Ancient Egypt. Raleigh N.C.: Lulu Books. ISBN 1-4116-0176-9.

Further reading

- Faulkner, Raymond Oliver (2000). The Egyptian Book of the Dead: The Book of Going Forth by Day. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. OCLC 46998261.

- Remler, Pat (2004). Egyptian Mythology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517024-5.