Religion:Crusader states

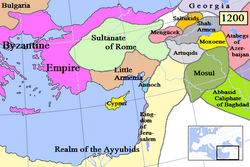

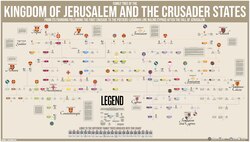

The Crusader states, or Outremer, were four Catholic polities that existed in the Levant from 1098 to 1291. Following the principals of feudalism, the foundation for these polities was laid by the First Crusade, which was proclaimed by the Latin Church in 1095 in order to reclaim the Holy Land after it was lost to the 7th-century Muslim conquest. Situated on the Eastern Mediterranean, the four states were, in order from north to south: the County of Edessa (1098–1150), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the County of Tripoli (1102–1289), and the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291). The three northern states covered an area in what is now southeastern Turkey, northwestern Syria, and northern Lebanon; and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the southernmost and most prominent state, covered an area in what is now Israel, the State of Palestine (the West Bank and the Gaza Strip), southern Lebanon, and western Jordan. The description "Crusader states" can be misleading, as from 1130 onwards, very few people among the Franks were Crusaders. Medieval and modern writers use the term "Outremer" as a synonym, derived from the French word for overseas.

By 1098, the Crusaders' armed pilgrimage to Jerusalem was passing through the Syria region. Edessa, under the rule of Greek Orthodoxy, was subject to a coup d'état in which the leadership was taken over by Baldwin of Boulogne, and Bohemond of Taranto remained as the ruling prince in the captured city of Antioch. The siege of Jerusalem in 1099 resulted in a decisive Crusader victory over the Fatimid Caliphate, after which territorial consolidation followed, including the taking of Tripoli. In 1144, Edessa fell to the Zengid Turks, but the other three realms endured until the final years of the 13th century, when they fell to the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. The Mamluks captured Antioch in 1268 and Tripoli in 1289, leaving only the Kingdom of Jerusalem, which had been severely weakened by the Ayyubid Sultanate after the siege of Jerusalem in 1244. The Crusader presence in the Levant collapsed shortly thereafter, when the Mamluks captured Acre in 1291, ending the Kingdom of Jerusalem nearly 200 years after it was founded. With all four of the states defeated and annexed, the survivors fled to the Kingdom of Cyprus, which had been established by the Third Crusade.

The study of the Crusader states in their own right, as opposed to being a sub-topic of the Crusades, began in 19th-century France as an analogy to the French colonial experience in the Levant, though this was rejected by 20th-century historians.[who?] Their consensus was that the Frankish population, as the Western Europeans were known at the time, lived as a minority society that was largely urban and isolated from the indigenous Levantine peoples, having separate legal and religious systems. The ancient Jewish communities that had survived and remained in the holy cities of Jerusalem, Tiberias, Hebron, and Safed since the Jewish–Roman wars and the destruction of the Second Temple were heavily persecuted in a pattern of rampant Christian antisemitism accompanying the Crusades.

Outremer

The terms Crusader states and Outremer (French: outre-mer, lit. 'overseas') describe the four feudal states established after the First Crusade in the Levant in around 1100: (from north to south) the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, the County of Tripoli, and the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The term Outremer is of medieval origin, whilst modern historians use Crusader states, and the term Franks for the European incomers. However, relatively few of the incoming Europeans took a crusader oath.[1][2] The Latin chronicles of the First Crusade, written in the early 11th century, called the Western Christians who came from Europe Franci irrespective of their ethnicity. Byzantine Greek sources use Φράγκοι Frangi and Arabic الإفرنجي al-Ifranji. Alternatively, the chronicles used Latini, or Latins. These medieval ethnonyms reflect that the settlers could be differentiated from the indigenous population by language and faith.[3] The Franks were mainly French-speaking Roman Catholics, while the natives were mostly Arabic- or Greek-speaking Muslims, Christians of other denominations, and Jews.[2][4]

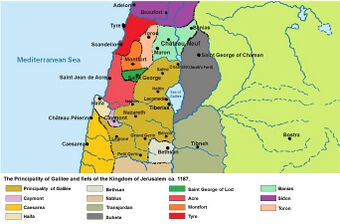

The Kingdom of Jerusalem extended over historical Palestine and at its greatest extent included some territory east of the Jordan River. The northern states covered what is now part of Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and Lebanon. These areas were historically called Syria (known to the Arabs as al-Sham) and Upper Mesopotamia. Edessa extended east beyond the Euphrates. In the Middle Ages the Crusader states were also called Syria or Syrie.[5] From around 1115, the ruler of Jerusalem was styled 'king of the Latins in Jerusalem'. Historian Hans Eberhard Mayer believes this reflected that only Latins held complete political and legal rights in the kingdom, and that the major division in the society was not between the nobility and the common people but between the Franks and the indigenous peoples.[6] Despite sometimes receiving homage from, and acting as regent for, the rulers of the other states; the king held no formalised overlord status, and those states remained legally outside the kingdom.[7]

Jews, Christians, and Muslims respected Palestine, known as the Holy Land, as an exceptionally sacred place. They all associated the region with the lives of the prophets of the Hebrew Bible. All of the holy sites in Judaism were found there, including the remains of the Second Temple, destroyed by the Romans in 70AD. The New Testament presented Palestine as the venue of the acts of Jesus and his Apostles. Islamic tradition described the region's principal city, Jerusalem, as the site of the Isra' and Mi'raj, Muhammad's miraculous night travel and ascension to Heaven. Places associated with holy people developed into shrines visited by pilgrims coming from faraway lands, often as an act of penance. The surge in Christian pilgrimage also inspired many Jews to return to the Holy Land. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre was built to commemorate Christ's crucifixion and resurrection in Jerusalem. The Church of the Nativity was thought to enclose his birthplace in Bethlehem. The Dome of the Rock and Al-Aqsa Mosque commemorated Muhammad's night journey.[8][9] Although the most sacred places of devotion were in Palestine, neighbouring Syria was also studded with popular shrines.[10] As a borderland of the Muslim world, Syria was an important theatre of jihad, though enthusiasm for pursuing it had faded by the end of the 11th century.[11] In contrast, the Catholic ideology of religious war quickly developed, culminating in the idea of crusades for lands claimed for Christianity.[10][12]

Background

Catholic Europe

Most crusades came from what had been the Carolingian Empire around 800. The empire had disintegrated, and two loosely unified successor states had taken its place: the Holy Roman Empire, which encompassed Germany, part of northern Italy, and the neighbouring lands; and France. Germany was divided into duchies, such as Lower Lorraine and Saxony, and their dukes did not always obey the emperors. Northern Italy was even less united, divided into numerous de-facto independent states, and the authority of the emperor was barely felt.[13] Carolingian's western successor state, France, wasn't united either, the French kings only controlled a small central region directly. Counts and dukes ruled other regions, and some of them were remarkably wealthy and powerful—in particular, the dukes of Aquitaine and Normandy, and the counts of Anjou, Champagne, Flanders, and Toulouse.[14]

Western Christians and Muslims interacted mainly through warring or commerce. During the 8th and 9th centuries, the Muslims were on the offensive, and commercial contacts primarily enriched the Islamic world. Europe was rural and underdeveloped, offering little more than raw materials and slaves in return for spices, cloth, and other luxuries from the Middle East.[15][16] Climate change during the Medieval Warm Period affected the Middle East and western Europe differently. In the east, it caused droughts, while in the west, it improved conditions for agriculture. Higher agricultural yields led to population growth and the expansion of commerce, and to the development of prosperous new military and mercantile elites.[17]

In Catholic Europe, state and society were organised along feudal lines. Landed estates were customarily granted in fief—that is, in return for services that the grantee, or vassal, was to perform for the grantor, or lord. A vassal owed fealty to the lord and was expected to provide military aid and advice to him.[18] Violence was endemic, and a new class of mounted warriors, the knights, emerged. Many built castles, and their feuds brought much suffering to the unarmed population. The development of the knightly class coincided with the subjection of the formerly free peasantry into serfdom, but the connection between the two processes is unclear.[19] As feudal lordships could be established by the acquiring land, western aristocrats willingly launched offensive military campaigns, even against faraway territories.[20] Catholic Europe's expansion in the Mediterranean began in the second half of the 11th century. Norman warlords conquered southern Italy from the Byzantines and ousted the Muslim rulers from Sicily; French aristocrats hastened to the Iberian peninsula to fight the Moors of Al-Andalus; and Italian fleets launched pillaging raids against the north African ports. This shift of power especially benefited merchants from the Italian city-states of Amalfi, Genoa, Pisa, and Venice. They replaced the Muslim and Jewish middlemen in the lucrative trans-Mediterranean commerce, and their fleets became the dominant naval forces in the region.[21][22]

On the eve of the Crusades, after a thousand years of reputedly uninterrupted succession of popes, the Papacy was Catholic Europe's oldest institution. The popes were seen as the Apostle Saint Peter's successors, and their prestige was high. In the west, the Gregorian Reform reduced lay influence on church life and strengthened papal authority over the clergy.[23][24] Eastern Christians continued to consider the popes as no more than one of the five highest ranking church leaders, titled patriarchs, and rejected the idea of papal supremacy. This opposition, together with differences in theology and liturgy, caused acrimonious disputes which escalated when a papal legate excommunicated the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in 1054. The patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem sided with the Ecumenical Patriarch against the Papacy, but the East–West Schism was not yet inevitable, and the Catholic and Orthodox Churches remained in full communion.[25] The Gregorian Reform enhanced the popes' influence on secular matters. To achieve political goals, popes excommunicated their opponents, placed entire realms under interdict and promised spiritual rewards to those who took up arms for their cause. In 1074 Pope Gregory VII even considered leading a military campaign against the Turks who had attacked Byzantine territories in Anatolia.[26]

Levant

Turkic migration permeated the Middle East from the 9th century. Muslim border raiders captured unconverted Turkic nomads in the Central Asian borderlands and sold them to Islamic leaders who used them as slave soldiers. These were known as ghilman or mamluk and were emancipated when converted to Islam. Mamluks were valued primarily because the link of their prospects to a single master generated extreme loyalty. In the context of Middle Eastern politics this made them more trustworthy than relatives.[lower-alpha 1] Eventually, some mamluk descendants climbed the Muslim hierarchy to become king makers or even dynastic founders.[27][28]

In the mid-11th century, a minor clan of Oghuz Turks named Seljuks, after the warlord Saljūq from Transoxiana, had expanded through Khurasan, Iran, and on to Baghdad. There, Saljūq's grandson Tughril was granted the title sultan—'power' in Arabic—by the Abbasid Caliph. The caliphs kept their legitimacy and prestige, but the sultans held political power.[29][30] Seljuk success was achieved by extreme violence. It brought disruptive nomadism to the sedentary society of the Levant, and set a pattern followed by other nomadic Turkic clans such as the Danishmendids and the Artuqids. The Great Seljuk Empire was decentralised, polyglot, and multi-national. A junior Seljuk ruling a province as an appanage was titled malik, Arabic for king.

Mamluk military commanders acting as tutors and guardians for young Seljuk princes held the position of atabeg ('father-commander'). If his ward held a province in appanage, the atabeg ruled it as regent for the underage malik. On occasion, the atabeg kept power after his ward reached the age of majority or died.[31][32] The Seljuks adopted and strengthened the traditional iqta' system of the administration of state revenues. This system secured the payment of military commanders through granting them the right to collect the land tax in a well-defined territory, but it exposed the taxpayers to an absent lord's greed and to his officials' arbitrary actions.[33][34] Although the Seljuk state worked when family ties and personal loyalty overlapped the leaders' personal ambitions, the lavish iqta' grants combined with rivalries between maliks, atabegs, and military commanders could lead to disintegration in critical moments.[35]

The region's ethnic and religious diversity led to alienation among the ruled populations. In Syria, the Seljuk Sunnis ruled indigenous Shias. In Cilicia and northern Syria, the Byzantines, Arabs, and Turks squeezed populations of Armenians. The Seljuks contested control of southern Palestine with Egypt, where Shia rulers ruled a majority Sunni populace through powerful viziers who were mainly Turkic or Armenian, rather than Egyptian or Arab.[36] The Seljuks and the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt hated each other, as the Seljuk saw themselves as defenders of the Sunni Abbasid Caliphate and Fatimid Egypt was the chief Shi'ite power in Islam.[37] The root of this was beyond cultural and racial conflict but originated in the splits within Islam following Muhammad's death. Sunnis supported a caliphal succession that began with one of his associates, Abu Bakr, while Shi'ites supported an alternative succession from his cousin and son-in-law, Ali.[38][39]

Islamic law granted the status of dhimmi, or protected peoples, to the People of the Book, like Christians and Jews. The dhimmi were second-class citizens, obliged to pay a special poll tax, the jizya, but they could practise their religion and maintain their own law courts.[40][41] Theological, liturgical, and cultural differences had given rise to the development of competing Christian denominations in the Levant before the 7th-century Muslim conquest. The Greek Orthodox natives, or Melkites, remained in full communion with the Byzantine imperial church, and their religious leaders often came from the Byzantine capital, Constantinople. In the 5th century, the Nestorians, and the Monophysite Jacobites, Armenians, and Copts, broke with the Byzantine state church. The Maronites' separate church organisation emerged under Muslim rule.[42]

During the late 10th and early 11th centuries, the Byzantine Empire had been on the offensive, recapturing Antioch in 969, after three centuries of Arab rule, and invading Syria.[43][44] Turkic brigands and their Byzantine, also often ethnically Turkic, counterparts called akritai indulged in cross-border raiding. In 1071, while securing his northern borders during a break in his campaigns against the Fatimid Caliphate, Sultan Alp Arslan defeated Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes at Manzikert. Romanos' capture and Byzantine factionalism that followed broke Byzantine border control. This enabled large numbers of Turkic warbands and nomadic herders to enter Anatolia. Alp Arslan's cousin Suleiman ibn Qutulmish seized Cilicia and entered Antioch in 1084. Two years later, he was killed in a conflict with the Great Seljuk Empire.[45] Between 1092 and 1094, Nizam al-Mulk, the Sultan Malik-Shah, the Fatimid Caliph, Al-Mustansir Billah and the vizier Badr al-Jamali all died.[46][47] Malik-Shah's brother Tutush and the atabegs of Aleppo and Edessa were killed in the succession conflict, and Suleiman's son Kilij Arslan I revived his father's Sultanate of Rum in Anatolia. The Egyptian succession resulted in a split in the Ismā'īlist branch of Shia Islam. The Persian missionary Hassan-i Sabbah led a breakaway group, creating the Nizari branch of Isma'ilism. This was known as the New Preaching in Syria and the Order of Assassins in western historiography. The Order used targeted murder to compensate for their lack of military power.[48]

The Seljuk invasions, the subsequent eclipse of the Byzantines and Fatimids, and the disintegration of the Seljuk Empire revived the old Levantine system of city-states.[49] The region had always been highly urbanised, and the local societies were organised into networks of interdependent settlements, each centred around a city or a major town.[50] These networks developed into autonomous lordships under the rule of a Turkic, Arab or Armenian warlord or town magistrate in the late 11th century.[51] The local quadis took control of Tyre and Tripoli, the Arab Banu Munqidh seized Shaizar, and Tutush's sons Duqaq and Ridwan succeeded in Damascus and Aleppo respectively, but their atabegs, Janah ad-Dawla and Toghtekin were in control. Ridwan's retainer Sokman ben Artuq held Jerusalem; Ridwan's father-in-law, Yağısıyan, ruled Antioch; and a warlord representing Byzantine interests, called Thoros, seized Edessa.[52] During this period the old Islamic conflict between Sunni and Shia made the Muslim peoples more likely to wage war on each other than on Christians.[53]

History

Foundation

The Byzantines augmented their armies with mercenaries from the Turks and Europe. This compensated for a shortfall caused by lost territory, especially in Anatolia.[54] In 1095 at the Council of Piacenza, Emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested support from Pope Urban II against the Seljuk threat.[55] What the Emperor probably had in mind was a relatively modest force, and Urban far exceeded his expectations by calling for the First Crusade at the later Council of Clermont. He developed a doctrine of bellum sacrum (Christian holy war) and, based mainly on Old Testament passages in which God leads the Hebrews to victory in war, reconciled this with Church teachings.[56] Urban's call for an armed pilgrimage for the liberation of the Eastern Christians and the recovery of the Holy Land aroused unprecedented enthusiasm in Catholic Europe. Within a year, tens of thousands of people, both commoners and aristocrats, departed for the military campaign.[57] Individual crusaders' motivations to join the crusade varied, but some of them probably left Europe to make a new permanent home in the Levant.[58]

Alexios cautiously welcomed the feudal armies commanded by western nobles. By dazzling them with wealth and charming them with flattery, Alexios extracted oaths of fealty from most of the Crusader commanders. As his vassals, Godfrey of Bouillon, nominally duke of Lower Lorraine; the Italo-Norman Bohemond of Taranto; Bohemond's nephew Tancred of Hauteville; and Godfrey's brother Baldwin of Bologne all swore that any territory gained which the Roman Empire had previously held, would be handed to Alexios' Byzantine representatives. Only Raymond IV, Count of Toulouse refused this oath, instead promising non-aggression towards Alexios.[59]

The Byzantine Tatikios guided the crusade on the arduous three-month march to besiege Antioch, during which the Franks made alliances with local Armenians.[60] Before reaching Antioch, Baldwin and his men left the main army and headed to the Euphrates river, engaging in local politics and seizing the fortifications of Turbessel and Rawandan, where the Armenian populace welcomed him.[61] Thoros, then ruler of this territory, could barely control or defend Edessa, so he tried to hire the Franks as mercenaries. Later, he went further and adopted Baldwin as his son in a power-share arrangement. In March 1098, a month after Baldwin's arrival, a Christian mob killed Thoros and acclaimed Baldwin as doux, the Byzantine title Thoros had used.[62] Baldwin's position was personal rather than institutional, and the Armenian governance of the city remained in place. Baldwin's nascent County of Edessa consisted of pockets separated from his other holdings of Turbessel, Rawandan and Samosata by the territory of Turkic and Armenian warlords and the Euphrates.[63]

As the crusaders marched towards Antioch, Syrian Muslims asked Sultan Barkiyaruq for help, but he was engaged in a power struggle with his brother Muhammad Tapar.[64] At Antioch, Bohemond persuaded the other leaders the city should be his if he could capture it, and Alexios did not come to claim it. Alexios withdrew, rather than join the siege, after Stephen, Count of Blois (who was deserting) told him defeat was imminent. In June 1098, Bohemond persuaded a renegade Armenian tower commander to let the crusaders into the city. They slaughtered the Muslim inhabitants and, by mistake, some local Christians.[65][66] The crusade leaders decided to return Antioch to Alexios as they had sworn to at Constantinople,[67] but when they learnt of Alexios' withdrawal, Bohemond claimed the city for himself. The other leaders agreed, apart from Raymond, who supported the Byzantine alliance.

This dispute resulted in the march stalling in north Syria. The crusaders were becoming aware of the chaotic state of Muslim politics through frequent diplomatic relations with the Muslim powers. Raymond indulged in a small expedition. He bypassed Shaizar and laid siege to Arqa to enforce the payment of a tribute.[68] In Raymond's absence, Bohemond expelled Raymond's last troops from Antioch and consolidated his rule in the developing Principality of Antioch.

Under pressure from the poorer Franks, Godfrey and Robert II, Count of Flanders reluctantly joined the eventually unsuccessful siege of Arqa. Alexios asked the crusade to delay the march to Jerusalem, so the Byzantines could assist. Raymond's support for this strategy increased division among the crusade leaders and damaged his reputation among ordinary crusaders.[69][70]

The crusaders marched along the Mediterranean coast to Jerusalem. On 15 July 1099, crusaders took the city after a siege lasting barely longer than a month. Thousands of Muslims and Jews were killed, and the survivors sold into slavery. Proposals to govern the city as an ecclesiastical state were rejected. Raymond refused the royal title, claiming only Christ could wear a crown in Jerusalem. This may have been to dissuade the more popular Godfrey from assuming the throne, but Godfrey adopted the title Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri ('Defender of the Holy Sepulchre') when he was proclaimed the first Frankish ruler of Jerusalem.[71] In Western Europe an advocatus was a layman responsible for the protection and administration of church estates.[72]

The foundation of these three crusader states did not change the political situation in the Levant profoundly. Frankish rulers replaced local warlords in the cities, but large-scale colonisation did not follow, and the new conquerors did not change the traditional organisation of settlements and property in the countryside.[73] The Muslim leaders were massacred or forced into exile, and the natives, accustomed to the rule of well-organised warbands, offered little resistance to their new lords.[74] Western Christianity's canon law recognised that peace treaties and armistices between Christians and Muslims were valid. The Frankish knights regarded the Turkic mounted warlords as their peers with familiar moral values, and this familiarity facilitated their negotiations with the Muslim leaders. The conquest of a city was often accompanied by a treaty with the neighbouring Muslim rulers who were customarily forced to pay a tribute for the peace.[75] The crusader states had a special position in Western Christianity's consciousness: many Catholic aristocrats were ready to fight for the Holy Land, although in the decades following the destruction of the large Crusade of 1101 in Anatolia, only smaller groups of armed pilgrims departed for Outremer.[76]

Consolidation (1099 to 1130)

The Fatimids' feud with the Seljuks hindered Muslim actions for more than a decade. Outnumbered by their enemies, the Franks remained in a vulnerable position, but they could forge temporary alliances with their Armenian, Arab, and Turkic neighbours. Each crusader state had its own strategic purpose during the first years of its existence. Jerusalem needed undisturbed access to the Mediterranean; Antioch wanted to seize Cilicia and the territory along the upper course of the Orontes River; and Edessa aspired to control the Upper Euphrates valley.[77] The most powerful Syrian Muslim ruler, Toghtekin of Damascus, took a practical approach to dealing with the Franks. His treaties establishing Damascene–Jerusalemite condominiums (shared rule) in debated territories created precedents for other Muslim leaders.[78][79]

In August 1099, Godfrey defeated the Fatimid vizier, Al-Afdal Shahanshah at Ascalon. When Daimbert of Pisa, the papal legate, arrived in the Levant with 120 Pisan ships, Godfrey gained much-needed naval support by backing him for the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, as well as granting him parts of Jerusalem and the Pisans a section of the port of Jaffa. Daimbert revived the idea of creating an ecclesiastic principality and extracted oaths of fealty from Godfrey and Bohemond.

When Godfrey died in 1100, his retainers occupied the Tower of David to secure his inheritance for his brother Baldwin. Daimbert and Tancred sought Bohemond's help against the Lotharingians, but the Danishmends captured Bohemond under Gazi Gümüshtigin while securing Antioch's northern marches. Before departing for Jerusalem, Baldwin ceded Edessa to his cousin, Baldwin of Bourcq. His arrival thwarted Daimbert, who crowned Baldwin as Jerusalem's first Latin king on Christmas Day 1100. By performing the ceremony, the Patriarch abandoned his claim to rule the Holy Land.[80][81]

Tancred remained defiant to Baldwin until an Antiochene delegation offered him the regency in March 1101. He ceded his Principality of Galilee to the king, but reserved the right to reclaim it as a fief if he returned from Antioch within fifteen months. For the next two years, Tancred ruled Antioch. He conquered Byzantine Cilicia and parts of Syria.[82] The Fatimid Caliphate attacked Jerusalem in 1101, 1102 and 1105, on the last occasion in alliance with Toghtekin. Baldwin I repulsed these attacks and with Genoese, Venetian, and Norwegian fleets conquered all the towns on the Palestinian coast except Tyre and Ascalon.[83]

Raymond laid the foundations of the fourth crusader state, the County of Tripoli. He captured Tartus and Gibelet and besieged Tripoli. His cousin William II Jordan continued the siege after Raymond's death in 1105. It was completed in 1109 when Raymond's son Bertrand arrived. Baldwin brokered a deal, sharing the territory between them, until William Jordan's death united the county. Bertrand acknowledged Baldwin's suzerainty, although William Jordan had been Tancred's vassal.[84]

When Bohemond was released for a ransom in 1103, he compensated Tancred with lands and gifts. Baldwin of Bourcq and his cousin and vassal, Joscelin of Courtenay, were captured while attacking Ridwan of Aleppo at Harran with Bohemond. Tancred assumed the regency of Edessa. The Byzantines took the opportunity to reconquer Cilicia. They took the port but not the citadel of Laodikeia.

Bohemond returned to Italy to recruit allies and gather supplies. Tancred assumed leadership in Antioch, and his cousin Richard of Salerno did the same in Edessa. In 1107, Bohemond crossed the Adriatic Sea and failed in besieging Dyrrachion in the Balkan Peninsula. The resulting Treaty of Devol forced Bohemond to restore Laodikeia and Cilicia to Alexios, become his vassal and reinstate the Greek patriarch of Antioch. Bohemond never returned. He died, leaving an underage son Bohemond II. Tancred continued as regent of Antioch and ignored the treaty. Richard's son, Roger of Salerno, succeeded as regent on Tancred's death in 1112.[85][86]

The fall of Tripoli prompted Sultan Muhammad Tapar to appoint the atabeg of Mosul, Mawdud, to wage jihad against the Franks. Between 1110 and 1113, Mawdud mounted four campaigns in Mesopotamia and Syria, but rivalry among his heterogeneous armies' commanders forced him to abandon the offensive on each occasion.[87][88] As Edessa was Mosul's chief rival, Mawdud directed two campaigns against the city.[89] They caused havoc, and the county's eastern region could never recover.[90] The Syrian Muslim rulers saw the Sultan's intervention as a threat to their autonomy and collaborated with the Franks. After an assassin, likely a Nizari, murdered Mawdud, Muhammad Tapar dispatched two armies to Syria, but both campaigns failed.[91]

As Aleppo remained vulnerable to Frankish attacks, the city leaders sought external protection. They allied with the adventurous Artuqid princes, Ilghazi and Balak, who inflicted crucial defeats on the Franks between 1119 and 1124, but could rarely prevent Frankish counter-invasions.[92][93]

In 1118 Baldwin of Bourcq succeeded Baldwin I as King of Jerusalem, naming Joscelin his successor in Edessa. After Roger was killed at Ager Sanguinis ('Field of Blood'), Baldwin II assumed the regency of Antioch for the absent Bohemond II. Public opinion attributed a series of disasters affecting the Outremer—defeats by enemy forces and plagues of locusts—as punishments for the Franks' sins. To improve moral standards, the Jerusalemite ecclesiastic and secular leaders assembled a council at Nablus and issued decrees against adultery, sodomy, bigamy, and sexual relations between Catholics and Muslims.[94]

A proposal by a group of pious knights about a monastic order for deeply religious warriors was likely first discussed at the council of Nablus. Church leaders quickly espoused the idea of armed monks, and within a decade, two military orders, the Knights Templar and Hospitaller, were formed.[95][96] As the Fatimid Caliphate no longer posed a major threat to Jerusalem, but Antioch and Edessa were vulnerable to invasion, the defence of the northern crusader states took much of Baldwin II's time. His absence, its impact on government, and his placement of relatives and their vassals in positions of power created opposition in Jerusalem. Baldwin's sixteen-month captivity led to a failed deposition attempt by some of the nobility, with the Flemish count, Charles the Good, considered as a possible replacement. Charles declined the offer.[90][97]

Baldwin had four daughters. In 1126, Bohemond reached the age of majority and married the second-oldest, Alice, in Antioch.[98] Aleppo had plunged into anarchy, but Bohemond II could not exploit this because of a conflict with Joscelin. The new atabeg of Mosul Imad al-Din Zengi seized Aleppo in 1128. The two major Muslim centres' union was especially dangerous for the neighbouring Edessa,[99][100] but it also worried Damascus's new ruler, Taj al-Muluk Buri.[101] Baldwin's eldest daughter Melisende was his heir. He married her to Fulk of Anjou, who had widespread western connections useful to the kingdom. After Fulk's arrival, Baldwin raised a large force for an attack on Damascus. This force included the leaders of the other crusader states, and a significant Angevin contingent provided by Fulk. The campaign was abandoned when the Franks' foraging parties were destroyed, and bad weather made the roads impassable. In 1130 Bohemond II was killed raiding in Cilicia, leaving Alice with their infant daughter, Constance. Baldwin II denied Alice control, instead resuming the regency until his death in 1131.[102][103]

Muslim revival (1131 to 1174)

On his deathbed Baldwin named Fulk, Melisende, and their infant son Baldwin III joint heirs. Fulk intended to revoke the arrangement, but his favouritism toward his compatriots roused strong discontent in the kingdom. In 1134, he repressed a revolt by Hugh II of Jaffa, a relative of Melisende, but was still compelled to accept the shared inheritance. He also thwarted frequent attempts by his sister-in-law Alice to assume the regency in Antioch, including alliances with Pons of Tripoli and Joscelin II of Edessa.[104] Taking advantage of Antioch's weakened position, Leo, a Cilician Armenian ruler, seized the Cilician plain.[105] In 1133, the Antiochene nobility asked Fulk to propose a husband for Constance, and he selected Raymond of Poitiers, a younger son of William IX of Aquitaine. Raymond finally arrived in Antioch three years later and married Constance.[106] He reconquered parts of Cilicia from the Armenians.[107] In 1137, Pons was killed battling the Damascenes, and Zengi invaded Tripoli. Fulk intervened, but Zengi's troops captured Pons' successor Raymond II, and besieged Fulk in the border castle of Montferrand. Fulk surrendered the castle and paid Zengi 50,000 dinars for his and Raymond's freedom.[108] Emperor Alexios' son and successor, John II Komnenos, reasserted Byzantine claims to Cilicia and Antioch. His military campaign compelled Raymond of Poitiers to give homage and agree that he would surrender Antioch by way of compensation if the Byzantines ever captured Aleppo, Homs, and Shaizar for him. [109] The following year the Byzantines and Franks jointly besieged Aleppo and Shaizar but could not take the towns. Zengi soon seized Homs from the Damascenes, but a Damascene–Jerusalemite coalition prevented his southward expansion.[110]

Joscelin made an alliance with the Artuqid Kara Arslan, who was Zengi's principal Muslim rival in Upper Mesopotamia. While Joscelin was staying west of the Euphrates at Turbessel, Zengi invaded the Frankish lands east of the river in late 1144. Before the end of the year, he captured the region, including the city of Edessa.[111][112] Losing Edessa strategically threatened Antioch and limited opportunities for a Jerusalemite expansion in the south. In September 1146, Zengi was assassinated, possibly on orders from Damascus. His empire was divided between his two sons, with the younger Nur ad-Din succeeding him in Aleppo. A power vacuum in Edessa allowed Joscelin to return to the city, but he was unable to take the citadel. When Nur ad-Din arrived, the Franks were trapped, Joscelin fled and the subsequent sack left the city deserted.[113]

The fall of Edessa shocked Western opinion, prompting the largest military response since the First Crusade. The new crusade consisted of two great armies led overland by Louis VII of France and Conrad III of Germany, arriving in Acre in 1148. The arduous march had greatly reduced the two rulers' forces. At a leadership conference, including the widowed Melisende and her son Baldwin III, they agreed to attack Damascus rather than attempt to recover distant Edessa. The attack on Damascus ended in a humiliating defeat and retreat.[114] Scapegoating followed the unexpected failure, with many westerners blaming the Franks. Fewer crusaders came from Europe to fight for the Holy Land in the next decades.[115] Raymond of Poitiers joined forces with the Nizari and Joscelin with the Rum Seljuks against Aleppo. Nur ad-Din invaded Antioch and Raymond was defeated and killed at Inab in 1149.[116] The next year Joscelin was captured and tortured and later died. Beatrice of Saone, his wife, sold the remains of the County of Edessa to the Byzantines with Baldwin's consent. Already 21 and eager to rule alone, Baldwin forced Melisende's retirement in 1152. In Antioch, Constance resisted pressure to remarry until 1153 when she chose the French nobleman Raynald of Châtillon as her second husband.[117]

From 1149, all Fatimid caliphs were children, and military commanders were competing for power. Ascalon, the Fatimids' last Palestinian bridgehead, hindered Frankish raids against Egypt, but Baldwin captured the town in 1153. The Damascenes feared further Frankish expansion, and Nur ad-Din seized the city with ease a year later. He continued to remit the tribute that Damascus' former rulers had offered to the Jerusalemite kings. Baldwin extracted tribute from the Egyptians as well.[118][119] Raynald lacked financial resources. He tortured the Latin Patriarch of Antioch, Aimery of Limoges, to appropriate his wealth and attacked the Byzantine's Cilician Armenians. When Emperor Manuel I Komnenos delayed the payment he had been promised, Raynald pillaged Byzantine Cyprus. Thierry, Count of Flanders, brought military strength from the West for campaigning. Thierry, Baldwin, Raynald and Raymond III of Tripoli attacked Shaizar. Baldwin offered the city to Thierry, who refused Raynald's demands he become his vassal, and the siege was abandoned.[120] After Nur ad-Din seized Shaizar in 1157, the Nizari remained the last independent Muslim power in Syria. As prospects for a new crusade from the West were poor, the Franks of Jerusalem sought a marriage alliance with the Byzantines. Baldwin married Manuel's niece, Theodora, and received a significant dowry. With his consent, Manuel forced Raynald into accepting Byzantine overlordship.[121][122]

The childless Baldwin III died in 1163. His younger brother Amalric had to repudiate his wife Agnes of Courtenay on grounds of consanguinity before his coronation, but the right of their two children, Baldwin IV and Sibylla, to inherit the kingdom was confirmed.[123] The Fatimid Caliphate had rival viziers, Shawar and Dirgham, both eager to seek external support. This gave Amalric and Nur ad-Din the opportunity to intervene. Amalric launched five invasions of Egypt between 1163 and 1169, on the last occasion cooperating with a Byzantine fleet, but he could not establish a bridgehead. Nur ad-Din appointed his Kurdish general Shirkuh to direct the military operations in Egypt. Weeks before Shirkuh died in 1169, the Fatimid caliph Al-Adid made him vizier.[124][125] His nephew Saladin, who ended the Shi'ite caliphate when Al-Adid died in September 1171, succeeded Shirkuh.[126][127] In March 1171, Amalric undertook a visit to Manuel in Constantinople to get Byzantine military support for yet another attack on Egypt. To this end, he swore fealty to the Emperor before his return to Jerusalem, but conflicts with Venice and Sicily prevented the Byzantines from campaigning in the Levant.[128][129] In theory, Saladin was Nur ad-Din's lieutenant, but mutual distrust hindered their cooperation against the crusader states. As Saladin remitted suspiciously small revenue payments to him, Nur ad-Din began gathering troops for an attack on Egypt, but he died in May 1174. He left an 11-year-old son, As-Salih Ismail al-Malik. Within two months, Amalric died. His son and successor, Baldwin IV, was 13 and a leper.[130][131]

Decline and survival (1174 to 1188)

The accession of underage rulers led to disunity both in Jerusalem and in Muslim Syria. In Jerusalem, the seneschal Miles of Plancy took control, but unknown assailants murdered him on the streets of Acre. With the baronage's consent, Amalric's cousin, Raymond III of Tripoli, assumed the regency for Baldwin IV as bailli. He became the most powerful baron by marrying Eschiva of Bures, the richest heiress of the kingdom, and gaining Galilee.[132][133] Nur ad-Din's empire quickly disintegrated. His eunuch confidant Gümüshtekin took As-Salih from Damascus to Aleppo. Gümüshtekin's rival, Ibn al-Muqaddam, seized Damascus but soon surrendered it to Saladin. By 1176, Saladin reunited much of Muslim Syria through warring against Gümüshtekin and As-Salih's relatives, the Zengids.[134][135] That same year, Emperor Manuel invaded the Sultanate of Rum to reopen the Anatolian pilgrimage route towards the Holy Land. His defeat at Myriokephalon weakened the Byzantines' hold on Cilicia.[136]

Upholding the balance of power in Syria was apparently Raymond's main concern during his regency. When Saladin besieged Aleppo in 1174, Raymond led a relief army to the city; next year, when a united Zengid army invaded Saladin's realm, he signed a truce with Saladin.[137] Gümüshtekin released Raynald of Châtillon and Baldwin's maternal uncle, Joscelin III of Courtenay, for a large ransom. They hastened to Jerusalem, and Raynald seized Oultrejourdain by marrying Stephanie of Milly. As Baldwin, a leper, was not expected to father children, his sister's marriage was to be arranged before his inevitable premature death from the disease. His regent, Raymond, chose William of Montferrat for Sybilla's husband. William was the cousin of both Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa and Louis VII of France. In 1176, Baldwin reached the age of 15 and majority, ending Raymond's regency. He revisited plans for an invasion of Egypt and renewed his father's pact with the Byzantines. Manuel dispatched a fleet of 70 galleys plus support ships to Outremer. As William had died, and Baldwin's health was deteriorating, the Franks offered the regency and the Egyptian invasion's command to Baldwin's crusader cousin Philip I, Count of Flanders. He wanted to be free to return to Flanders and rejected both offers.[138][139] The plan for the invasion was abandoned, and the Byzantine fleet sailed for Constantinople.[140]

Baldwin negotiated a marriage between Hugh III, Duke of Burgundy, and Sibylla, but the succession crisis in France prevented him from sailing. Tension between Baldwin's maternal and paternal relatives grew. When Raymond and Bohemond, both related to him on his father's side, came to Jerusalem unexpectedly before Easter in 1180, Baldwin panicked, fearing they had arrived to depose him and elevate Sibylla to the throne under their control. To thwart their coup, he sanctioned her marriage to Guy of Lusignan, a young aristocrat from Poitou. Guy's brother Aimery held the office of constable of Jerusalem, and their family had close links to the House of Plantagenet. Baldwin's mother and her clique marginalised Raymond, Bohemond and the influential Ibelin family.[141][142] To prepare for a military campaign against the Seljuks of Rum, Saladin concluded a two-year truce with Baldwin and, after launching a short but devastating campaign along the coast of Tripoli, with Raymond. For the first time in the history of Frankish–Muslim relations, the Franks could not set conditions for the peace.[143][144] Between 1180 and 1183, Saladin asserted his suzerainty over the Artuqids, concluded a peace treaty with the Rum Seljuks, seized Aleppo from the Zengids and re-established the Egyptian navy. Meanwhile, after the truce expired in 1182, Saladin demonstrated the strategic advantage he had by holding both Cairo and Damascus. While he faced Baldwin in Oultrejordain, his troops from Syria pillaged Galilee.[112][145] The Franks adopted a defensive tactic and strengthened their fortresses. In February 1183, a Jerusalemite assembly levied an extraordinary tax for defence funding. Raynald was the sole Frankish ruler to pursue an offensive policy. He attacked an Egyptian caravan and built a fleet for a naval raid into the Red Sea.[146]

Byzantine influence declined after Manuel died in 1180. Bohemond repulsed his Byzantine wife Theodora and married Sybil, an Antiochene noblewoman with a bad reputation. Patriarch Aimery excommunicated him and the Antiochene nobles who opposed the marriage fled to the Cilician Armenian prince, Ruben III.[147][148] Saladin granted a truce to Bohemond and made preparations for an invasion of Jerusalem where Guy took command of the defence.[149] When Saladin invaded Galilee, the Franks responded with what William of Tyre described in his contemporaneous chronicle as their largest army in living memory but avoided fighting a battle. After days of fierce skirmishing, Saladin withdrew towards Damascus. Baldwin dismissed Guy from his position as bailli, apparently because Guy had proved unable to overcome factionalism in the army. In November 1183, Baldwin made Guy's five-year-old stepson, also called Baldwin, co-ruler, and had him crowned king while attempting to annul the marriage of Guy and Sibylla. Guy and Sibylla fled to Ascalon, and his supporters vainly intervened on their behalf at a general council. An embassy to Europe was met with offers of money but not of military support. Already dying, Baldwin IV appointed Raymond bailli for 10 years, but charged Joscelin with the ailing Baldwin V's guardianship. As there was no consensus on what should happen if the boy king died, it would be for the pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, the kings of France and England to decide whether his mother Sibylla or her half-sister Isabella had stronger claim to the throne. Bohemond was staying at Acre around this time, allegedly because Baldwin IV wanted to secure Bohemond's support for his decisions on the succession.[150][151] Back in Antioch, Bohemond kidnapped Ruben of Cilicia and forced him into becoming his vassal.[152]

Saladin signed a four-year truce with Jerusalem and attacked Mosul. He could not capture the city but extracted an oath of fealty from Mosul's Zengid ruler, Izz al-Din Mas'ud, in March 1186. A few months later, Baldwin V died, and a power struggle began in Jerusalem. Raymond summoned the barons to Nablus to a general council. In his absence, Sybilla's supporters, led by Joscelin and Raynald, took full control of Jerusalem, Acre and Beirut. Patriarch Heraclius of Jerusalem crowned her queen and appointed Guy her co-ruler. The barons assembling at Nablus offered the crown to Isabella's husband Humphrey IV of Toron, but he submitted to Sybilla to avoid a civil war. After his desertion, all the barons but Baldwin of Ibelin and Raymond swore fealty to the royal couple. Baldwin went into exile, and Raymond forged an alliance with Saladin. Raynald seized another caravan, which violated the truce and prompted Saladin to assemble his forces for the jihād. Raymond allowed Muslim troops to pass through Galilee to raid around Acre. His shock at the Frankish defeat in the resulting Battle of Cresson brought him to reconciliation with Guy.[153][154]

Guy now gathered a large force, committing all of his kingdom's available resources. The leadership divided on tactics. Raynald urged an offensive, while Raymond proposed defensive caution, although Saladin was besieging his castle at Tiberias. Guy decided to deal with the siege. The march towards Tiberias was arduous, and Saladin's troops overwhelmed the exhausted Frankish army at the Horns of Hattin on 4 July 1187. Hattin was a massive defeat for the Franks. Nearly all the major Frankish leaders were taken prisoner, but only Raynald and the armed monks of the military orders were executed. Raymond was among the few Frankish leaders who escaped captivity. He fell seriously ill after reaching Tripoli. Within months after Hattin, Saladin conquered almost the entire kingdom. The city of Jerusalem surrendered on 2 October 1187. There were no massacres following the conquest, but tens of thousands of Franks were enslaved. Those who could negotiate a free passage or were ransomed swarmed to Tyre, Tripoli, or Antioch. Conrad of Montferrat commanded the defences of Tyre. He was William's brother and arrived only days after Hattin. The childless Raymond died, and Bohemond's younger son, also called Bohemond, assumed power in Tripoli.[155] After news of the Franks' devastating defeat at Hattin reached Italy, Pope Gregory VIII called for a new crusade. Passionate sermons raised religious fervour, and it is likely that more people took the crusader oath than during recruitment for the previous crusades.[156]

Bad weather and growing discontent among his troops forced Saladin to abandon the siege of Tyre and allow his men to return to Iraq, Syria, and Egypt early in 1188. In May, Saladin turned his attention to Tripoli and Antioch. The arrival of William II of Sicily's fleet saved Tripoli. Saladin released Guy on the condition that he go overseas and never bear arms against him.[157] Historian Thomas Asbridge proposes that Saladin likely anticipated that a power struggle between Guy and Conrad was inevitable and it could weaken the Franks. Indeed, Guy failed to depart for Europe.[158] In October, Bohemond asked Saladin for a seven-month truce, offering to surrender the city of Antioch if help did not arrive. Saladin's biographer Ali ibn al-Athir wrote, after the Frankish castles were starved into submission, that "the Muslims acquired everything from as far as Ayla to the furthest districts of Beirut with only the interruption of Tyre and also all the dependencies of Antioch, apart from al-Qusayr".[159]

Recovery and civil war (1189 to 1243)

Guy of Lusignan, his brother Aimery, and Gerard de Ridefort, grand master of the Templars, gathered about 600 knights in Antioch. They approached Tyre, but Conrad of Montferrat refused them entry, convinced Guy had forfeited his claim to rule when Saladin conquered his kingdom. Guy and his comrades knew western crusaders would arrive soon and risked a token move on Acre in August 1189. Crusader groups from many parts of Europe joined them. Their tactic surprised Saladin and prevented him from resuming the invasion of Antioch.[160][161] Three major crusader armies departed for the Holy Land in 1189–1190. Frederick Barbarossa's crusade ended abruptly in June 1190 when he drowned in the Saleph River in Anatolia. Only fragments of his army reached Outremer. Philip II of France landed at Acre in April 1191, and Richard I of England arrived in May. During his voyage, Richard had seized Cyprus from the island's self-declared emperor Isaac Komnenos.[162] Guy and Conrad had reconciled, but their conflict returned when Sybilla of Jerusalem and her two daughters by Guy died. Conrad married the reluctant Isabella, Sybilla's half-sister and heir, despite her marriage to Humphrey of Toron, and gossip about his two living wives.[163][164]

After an attritional siege, the Muslim garrison surrendered Acre, and Philip and most of the French army returned to Europe. Richard led the crusade to victory at Arsuf, capturing Jaffa, Ascalon and Darum. Internal dissension forced Richard to abandon Guy and accept Conrad's kingship. Guy was compensated with possession of Cyprus. In April 1192, Conrad was assassinated in Tyre. Within a week, the widowed Isabella was married to Henry, Count of Champagne.[165] Saladin did not risk a defeat in a pitched battle, and Richard feared the exhausting march across arid lands towards Jerusalem. As he fell ill and needed to return home to attend to his affairs, a three-year truce was agreed in September 1192. The Franks kept land between Tyre and Jaffa, but dismantled Ascalon; Christian pilgrimages to Jerusalem were allowed. Frankish confidence in the truce was not high. In April 1193, Geoffroy de Donjon, head of the Knights Hospitaller, wrote in a letter, 'We know for certain that since the loss of the land the inheritance of Christ cannot easily be regained. The land held by the Christians during the truces remains virtually uninhabited.'[166][167] The Franks' strategic position was not necessarily detrimental: they kept the coastal towns and their frontiers shortened. Their enclaves represented a minor threat to the Ayyubids' empire in comparison with the Artuqids, Zengids, Seljuks of Rum, Cilician Armenians or Georgians in the north. After Saladin died in March 1193, none of his sons could assume authority over his Ayyubid relatives, and the dynastic feud lasted for almost a decade.[167][168] The Ayyubids agreed near-constant truces with the Franks and offered territorial concessions to keep the peace.[169]

Bohemond III of Antioch did not include his recalcitrant Cilician Armenian vassal Leo in his truce with Saladin in 1192. Leo was Ruben III's brother. When Ruben died, Leo replaced his daughter and heir, Alice. In 1191, Saladin abandoned a three-year occupation of the northern Syrian castle of Bagras, and Leo seized it, ignoring claims of the Templars and Bohemond. In 1194, Bohemond accepted Leo's invitation to discuss Bagras' return, but Leo imprisoned him, demanding Antioch for his release. The Greek population and the Italian community rejected the Armenians, and formed a commune under Bohemond's eldest son, Raymond. Bohemond was released when he abandoned his claims on Cilicia, forfeiting Bagras and marrying Raymond to Alice. Any male heir of this marriage was expected to be the heir to both Antioch and Armenia. When Raymond died in 1197, Bohemond sent Alice and Raymond's posthumous son Raymond-Roupen to Cilicia. Raymond's younger brother Bohemond IV came to Antioch, and the commune recognised him as their father's heir.[170] In September 1197, Henry of Champagne died after falling out a palace window in the kingdom's new capital Acre. The widowed Isabella married Aimery of Lusignan who had succeeded Guy in Cyprus.[171] Saladin's ambitious brother Al-Adil I, reunited Egypt and Damascus under his rule by 1200. He expanded the truces with the Franks and enhanced commercial contacts with Venice and Pisa.[168] Bohemond III died in 1201. The commune of Antioch renewed its allegiance to Bohemond IV, although several nobles felt compelled to support Raymond-Roupen and joined him in Cilicia. Leo of Cilicia launched a series of military campaigns to assert Raymond-Roupen's claim to Antioch. Bohemond made alliances with Saladin's son, Az-Zahir Ghazi of Aleppo, and with Suleiman II, the Sultan of Rum. As neither Bohemond nor Leo could muster enough troops to defend their Tripolitan or Cilician hinterland against enemy invasions or rebellious aristocrats and to garrison Antioch simultaneously, the War of the Antiochene Succession lasted for more than a decade.[172]

The Franks knew they could not regain the Holy Land without conquering Egypt. The leaders of the Fourth Crusade planned an invasion of Egypt but sacked Constantinople instead.[173] Aimery and Isabella died in 1205. Isabella's daughter by Conrad, Maria of Montferrat, succeeded, and Isabella's half-brother, John of Ibelin, became regent. The regency ended with Maria's marriage in 1210 to John of Brienne, a French aristocrat and experienced soldier. After her death two years later, John ruled as regent for their infant daughter, Isabella II.[174] He participated in a military campaign against Cilicia, but it did not damage Leo's power. Leo and Raymond-Roupen had exhausted Antioch with destructive raids and occupied the city in 1216. Raymond-Roupen was installed as prince and Leo restored Bagras to the Templars. Raymond-Roupen could not pay for the aristocrats' loyalty in his impoverished principality and Bohemond regained Antioch with local support in 1219.[175] The personal union between Antioch and Tripoli proved lasting, but in fact both crusader states disintegrated into small city-states.[176] Raymond-Roupen fled to Cilicia, seeking Leo's support, and when Leo died in May, attempted to gain the throne against Leo's infant daughter Isabella.[175]

John of Brienne was leader of a gathering crusade but Frederick II, the ruler of Germany and Sicily, was expected to assume control on his arrival; the papal legate, Cardinal Pelagius, controlled the finances from the west. The crusaders invaded Egypt and captured Damietta in November 1219. The new sultan of Egypt Al-Kamil repeatedly offered the return of Jerusalem and the Holy Land in exchange for the crusaders' withdrawal. His ability to implement his truce proposals was questionable for his brother Al-Mu'azzam Isa ruled the Holy Land. The crusaders knew that their hold on the territory would not be secure as long as the castles in Oultrejourdain remained in Muslim hands. Prophecies about their inevitable victory spread in their camp, and Al-Adil's offer was rejected. After twenty-one months of stalemate, the crusaders marched on Cairo before being trapped between the Nile floods and the Egyptian army. The crusaders surrendered Damietta in return for safe conduct, ending the crusade. [177] While staying in Damietta, Cardinal Pelagius sent reinforcements to Raymond-Roupen in Cilicia, but Constantine of Baberon, who was regent for the Cilician queen, acted quickly. He captured Raymond-Roupen, who died in prison. The queen was married to Bohemond's son, Philip to cement an alliance between Cilicia and Antioch. A feud between the two nations broke out again after neglected Armenian aristocrats murdered Philip in late 1224. An alliance between the Armenians and his former Ayyubid allies in Aleppo foiled Bohemond's attempts at revenge.[178]

Frederick renewed his crusader oath on his imperial coronation in Rome in 1220. He did not join the Egyptian crusade but reopened the negotiations with Al-Adil over the city of Jerusalem. In 1225, Frederick married Isabella II and assumed the title of king of Jerusalem. Two years later, Al-Adil promised to abandon all lands conquered by Saladin in return for Frankish support against Al-Mu'azzam. An epidemic prevented Frederick's departure for a crusade, and Pope Gregory IX excommunicated him for repeatedly breaking his oath. In April 1228, Isabella died after giving birth to Conrad. Without seeking a reconciliation with the Pope, Frederick sailed for the crusade. His attempts to confiscate baronial fiefs brought him into conflict with the Frankish aristocrats. As Al-Mua'zzam had died, Frederick made the most of his diplomatic skills to achieve the partial implementation of Al-Adil's previous promise. They signed a truce for ten years, ten months, and ten days (the maximum period for a peace treaty between Muslims and Christians, according to Muslim custom). It restored Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth and Sidon to the Franks while granting Temple Mount to the Muslims. The native Franks were unenthusiastic about the treaty because it was questionable whether it could be defended. Frederick left for Italy in May 1229, and never returned.[179][180] He sent Richard Filangieri, with an army, to rule the kingdom of Jerusalem as his bailli. The Ibelins denied Frederick's right to appoint his lieutenant without consulting the barons, and Outremer plunged into a civil war, known as the War of the Lombards. Filangieri occupied Beirut and Tyre, but the Ibelins and their allies firmly kept Acre and established a commune to protect their interest.[181] Pope Gregory IX called for a new crusade in preparation for the expiry of the truce. Between 1239 and 1241, wealthy French and English nobles like Theobald I of Navarre and Richard of Cornwall led separate military campaigns to the Holy Land. They followed Frederick's tactics of forceful diplomacy and played rival factions off against each other in the succession disputes that followed Al-Kamil's death. Richard's treaty with Al-Kamil's son, As-Salih Ayyub, restored most land west of the Jordan River to the Franks.[182][183] Conrad reached the age of majority in 1243 but failed to visit Outremer. Arguing that Conrad's heir presumptive was entitled to rule in his absence, the Jerusalemite barons elected his mother's maternal aunt, Alice of Champagne, as regent. The same year, they captured Tyre, the last centre of Frederick's authority in the kingdom.[181]

Destruction by the Mamluks (1244 to 1291)

The Mongol Empire's westward expansion reached the Middle East when the Mongols conquered the Khwarazmian Empire in Central Asia in 1227. Part of the Khwarazmian army fled to eastern Anatolia and these masterless Turkic soldiers offered their services to the neighbouring rulers for pay.[184] Western Christians regarded the Mongols as potential allies against the Muslims because some Mongol tribes adhered to Nestorian Christianity. In fact, most Mongols were pagans with a strong belief in their Great Khan's divine right to universal rule, and they demanded unconditional submission from both Christians and Muslims.[185] As-Salih Ayyub hired the Khwarazmians and garrisoned new mamluk troops in Egypt, alarming his uncle As-Salih Ismail, Emir of Damascus. Ismail bought the Franks' alliance by a promise to restore 'all the lands that Saladin had reconquered'. Catholic priests took possession of the Dome of the Rock, but in July 1244 Khwarazmians marching towards Egypt sacked Jerusalem unexpectedly. The Franks gathered all available troops and joined Ismail near Gaza, but the Khwarazmians and Egyptians defeated the Frankish and Damascene coalition at La Forbie on 18 October. Few Franks escaped from the battlefield. As-Salah captured most of the crusaders' mainland territory, restricting the Franks to a few coastal towns.[186][187] Louis IX of France launched a failed crusade against Egypt in 1249. He was captured near Damietta with the remnants of his army, and ransomed days after the Bahri Mamluks assumed power in Egypt through murdering As-Salih's son Al-Muazzam Turanshah in May 1250.[188] Louis spent four more years in Outremer. As the kingdom's effective ruler, he conducted negotiations with both the Syrian Ayyubids and the Egyptian Mamluks and refortified the coastal towns. He sent an embassy from Acre to the Great Khan Güyük, offering an anti-Muslim alliance to the Mongols.[189]

Feuds between rival candidates to the regency and commercial conflicts between Venice and Genoa resulted in a new civil war in 1256 known as the War of Saint Sabas. The pro-Venetian Bohemond VI's conflict with his Genoese vassals the Embriaci brought the war to Tripoli and Antioch.[190] In 1258, the Ilkhan Hulagu, younger brother of the Great Khan Möngke, sacked Baghdad and ended the Abbasid Caliphate. Two years later, Hethum I of Cilicia and Bohemond VI joined forces with the Mongols in the sack of Aleppo, when Bohemond set fire to its mosque, and in the conquest of northern Syria. The Mongols emancipated the Christians from their dhimmi status, and the local Christian population cooperated with the conquerors. Jerusalem remained neutral when the Mamluks of Egypt moved to confront the Mongols after Hulagu, and much of his force moved east on the death of Möngke to address the Mongol succession. The Mamluks defeated the greatly reduced Mongol army at Ain Jalut. On their return, the Mamluk sultan Qutuz was assassinated and replaced by the general Baibars. Baibars revived Saladin's empire by uniting Egypt and Syria and held Hulagu in check through an alliance with the Mongols of the Golden Horde.[191][192] He reformed governance in Egypt, giving power to the elite mamluks. The Franks did not have the military capability to resist this new threat. A Mongol garrison was stationed at Antioch, and individual Frankish barons concluded separate truces with Baibars. Determined to conquer the crusader states, he captured Caesarea and Arsuf in 1265 and Safed in 1266, and sacked Antioch in 1268. Jaffa surrendered and Baibers weakened the military orders by capturing the castles of Krak des Chevaliers and Montfort before returning his attention to the Mongols of the Ilkhanate for the rest of his life. Massacres of the Franks and native Christians regularly followed a Mamluk conquest.[193][194]

In 1268, the new Sicilian king Charles I of Anjou executed Conradin, the titular king of Jerusalem, in Naples after his victory at Tagliacozzo.[195] Isabella I's great grandson Hugh III of Cyprus and her granddaughter Maria of Antioch disputed the succession. The barons preferred Hugh, but in 1277 Maria sold her claim to Charles. He sent Roger of San Severino to act as bailli. With the support of the Templars, he blocked Hugh's access to Acre, forcing him to retreat to Cyprus, again leaving the kingdom without a resident monarch.[196] The Mongols of the Ilkhanate sent embassies to Europe proposing anti-Mamluk alliances, but the major western rulers were reluctant to launch a new crusade for the Holy Land. The War of the Sicilian Vespers weakened Charles's position in the west. After his death in 1285, Henry II of Cyprus was acknowledged as Jerusalem's nominal king, but the rump kingdom was in fact a mosaic of autonomous lordships, some under Mamluk suzerainty.[197] In 1285, the death of the warlike Ilkhan Abaqa, combined with the Pisan and Venetian wars with the Genoese, finally gave the Mamluk sultan, Al-Mansur Qalawun, the opportunity to expel the Franks. In 1289 he destroyed Genoese-held Tripoli, enslaving or killing its residents. In 1290, Italian crusaders broke his truce with Jerusalem by killing Muslim traders in Acre. Qalawun's death did not hinder the successful Mamluk siege of the city in 1291. Those who could fled to Cyprus, while those who could not were slaughtered or sold into slavery. Without hope of support from the West, Tyre, Beirut, and Sidon all surrendered without a fight. The Mamluk policy was to destroy all physical evidence of the Franks; the destruction of the ports and fortified towns ruptured the history of a coastal city civilisation rooted in antiquity.[198]

Government and institutions

Modern historiography has focused on the kingdom of Jerusalem. Possibly this is related to it being the objective of the First Crusade, as well as the perception of the city being the centre and chief city of medieval Christendom. However, research into the kingdom does not provide a comprehensive common template for the development of the other Latin settlements.[199] Jerusalem's royal administration was based in the city until it was lost, and then in Acre. It featured the typical household officers of most European rulers: a cleric-led chancery, constable, marshal, chamberlain, chancellor, seneschal and butler. Royal territory was directly administered by Viscounts. [7] All tangible evidence of the written law was lost in 1187 when the Franks lost the city of Jerusalem to the Muslims.[200] The courts of the princes of Antioch were similar and created the Italo-Norman laws that were also later adopted by Cilician Armenia, known as the Assizes of Antioch. These have survived in 13th-century Armenian translations. Relationships among Antioch's various Frankish, Syrian, Greek, Jewish, Armenian, and Muslim inhabitants were generally good.[201] The brief existence of the uniquely-landlocked Edessa means it is the least studied, but its history is traceable to Armenian and Syriac chronicles in addition to Latin sources. Like Jerusalem the political institutions appear to have reflected the northern French roots of the founders, although the membership of city councils included indigenous Christians. The population was diverse, including Armenian Orthodox, Greeks known as Melkites, Syrian Orthodox known as Jacobites, and Muslims.[202] In Tripoli, the fourth Frankish state, Raymond of Saint-Gilles and his successors ruled directly over several towns, granting the rest as fiefs to lords originating in Languedoc and Provence, and Gibelet was given to the Genoese in return for naval support. In the 12th century this system provided a total of 300 knights, a much smaller army than Antioch or Jerusalem. Architectural and artistic activity in Lebanese churches provide evidence that the indigenous populations prospered under Frankish rule, in part due to its remoteness from the worst impacts of Saladin’s conquests in 1187–1188. These were Arabic-speaking Melkites, Monophysites, Nestorians, Syrians, and large numbers of Syriac-speaking Maronites with their own clerical hierarchies. The Greek Orthodox Church was restricted, as in Jerusalem. There were similar self-governing Muslim communities of Druze and Alawites, including Isma’ili, in the frontier areas to the north. The multi-ethnic structure may well have been more pronounced in Tripoli and in the 12th century there may have been a southern French culture, although this characteristic faded over time.[203]

The king of Jerusalem's foremost role was as leader of the feudal host during the near-constant warfare in the early decades of the 12th century. The kings rarely awarded land or lordships, and those they did frequently became vacant and reverted to the crown because of the high mortality rate. Their followers' loyalty was rewarded with city incomes. Through this, the domain of the first five rulers was larger than the combined holdings of the nobility. These kings of Jerusalem had greater internal power than comparative western monarchs, but they lacked the personnel and administrative systems necessary to govern such a large realm.[204]

In the second quarter of the century, magnates like Raynald of Châtillon, Lord of Oultrejordain, and Raymond III, Count of Tripoli, Prince of Galilee, established baronial dynasties and often acted as autonomous rulers. Royal powers were done away with, and governance was undertaken within the feudatories. The remaining central control was exercised at the High Court or Haute Cour, which was also known in Latin as Curia generalis and Curia regis, or in vernacular French as parlement. These meetings were between king and tenants in chief. The duty of the vassal to give counsel developed into a privilege and then the monarch's legitimacy depended on the court's agreement.[205] The High Court was the great barons' and the king's direct vassals. It had a quorum of the king and three tenants-in-chief. In 1162, the assise sur la ligece (roughly, 'Assize on liege-homage') expanded the court's membership to all 600 or more fief-holders. Those paying direct homage to the king became members of the Haute Cour. By the end of the 12th century, they were joined by the leaders of the military orders and in the 13th century the Italian communes.[206] The leaders of the Third Crusade ignored the monarchy. The kings of England and France agreed on the division of future conquests, as if there was no need to consider the local nobility. Prawer felt the weakness of the crown of Jerusalem was demonstrated by the rapid offering of the throne to Conrad of Montferrat in 1190 and then Henry II, Count of Champagne, in 1192 although this was given legal effect by Baldwin IV's will stipulating if Baldwin V died a minor, the pope, the kings of England and France, and the Holy Roman Emperor would decide the succession.[207]

Prior to the 1187 defeat at Hattin, laws developed by the court were recorded as assises in Letters of the Holy Sepulchre.[200] All written law was lost in the fall of Jerusalem. The legal system was now largely based on custom and the memory of the lost legislation. The renowned jurist Philip of Novara lamented, 'We know [the laws] rather poorly, for they are known by hearsay and usage...and we think an assize is something we have seen as an assize...in the kingdom of Jerusalem [the barons] made much better use of the laws and acted on them more surely before the land was lost.' An idyllic view of the early 12th century legal system was created. The barons reinterpreted the assise sur la ligece—which Almalric I intended to strengthen the crown—to constrain the monarch instead, particularly regarding the monarch's right to confiscate feudal fiefs without trial. The loss of the vast majority of rural fiefs led the baronage to evolve into an urban mercantile class where knowledge of the law was a valuable, well-regarded skill and a career path to higher status.[208]

After Hattin, the Franks lost their cities, lands, and churches. Barons fled to Cyprus and intermarried with leading new emigres from the Lusignan, Montbéliard, Brienne and Montfort families. This created a separate class—the remnants of the old nobility with a limited understanding of the Latin East. This included the king-consorts Guy, Conrad, Henry, Aimery, John, and the absent Hohenstaufen dynasty that followed.[209] The barons of Jerusalem in the 13th century have been poorly regarded by both contemporary and modern commentators: their superficial rhetoric disgusted Jacques de Vitry; Riley-Smith writes of their pedantry and the use of spurious legal justification for political action. The barons valued this ability to articulate the law.[210] This is evidenced by the elaborate and impressive treatises of the baronial jurists from the second half of the 13th century.[211]

From May 1229, when Frederick II left the Holy Land to defend his Italian and German lands, monarchs were absent. Conrad was titular king from 1225 until 1254, and his son Conradin until 1268 when Charles of Anjou executed him. The monarchy of Jerusalem had limited power in comparison with the West, where rulers developed bureaucratic machinery for administration, jurisdiction, and legislation through which they exercised control.[212] In 1242 the Barons prevailed and appointed a succession of Ibelin and Cypriot regents.[213] Centralised government collapsed in the face of independence exercised by the nobility, military orders, and Italian communes. The three Cypriot Lusignan kings who succeeded lacked the resources to recover the lost territory. One claimant sold the title of king to Charles of Anjou. He gained power for a short while but never visited the kingdom. [214]

Military

Size and recruitment

All estimates of the size of Frankish and Muslim armies are uncertain; existing accounts indicate that it is probable that the Franks of Outremer raised the largest armies in the Catholic world. As early as 1111, the four crusader states fielded 16,000 troops to launch a joint military campaign against Shaizar. Edessa and Tripoli raised armies numbering 1,000–3,000 troops, Antioch and Jerusalem deployed 4,000–6,000 soldiers. In comparison, William the Conqueror commanded 5,000–7,000 troops at Hastings and 12,000 crusaders fought against the Moors at Las Navas de Tolosa in Iberia.[215] Among the Franks' early enemies, the Fatimids possessed 10,000–12,000 troops, the rulers of Aleppo had 7,000–8,000 soldiers, and the Damascene atabegs commanded 2,000–5,000 troops. The Artuqids could hire as many as 30,000 Turks, but these nomadic warriors were unfit for lengthy sieges. After uniting Egypt, Syria, and much of Iraq, Saladin raised armies around 20,000 strong. Egyptian money and Syrian manpower represented the two critical factors underpinning Saladin's military might during the period.[216] In response, the Franks quickly increased their military force up to around 18,000 troops by 1183, but not without implementing austerity measures.[217] In the 13th century, the control of Acre's lucrative commerce provided the resources to maintain sizeable armies.[218] At La Forbie, 16,000 Frankish warriors perished in the battlefield, but this was the last occasion when a united Jerusalemite army fought a pitched battle.[219] During the 1291 siege of Acre, about 15,000 Frankish troops defended the city against more than 60,000 Mamluk warriors.[220]

The crusader states' military power depended mainly on four major categories of soldiery: vassals, mercenaries, visitors from the west, and troops provided by the military orders.[221] Vassals were expected to perform their military duties in person as fully armed knights, or more lightly armoured serjants. Unmarried female fief holders had to hire mercenaries; their wards represented underage vassals. Disabled men and men over sixty were required to cede their horses and arms to their lords. Vassals who owed the service of more than one soldier had to mobilise their own vassals or employ mercenaries.[222] A feudal lord's army could be sizeable. For example, 60 cavalrymen and 100 footmen accompanied Richard of Salerno, then lord of Marash, during a joint Antiochene–Edessene campaign against Mawdud in 1111.[223] Complaints about Frankish rulers' difficulties in paying off their troops abound, showing the importance of mercenary troops in Levantine warfare. Mercenaries were hired regularly for military campaigns, for garrisoning forts and particularly in Antioch, for serving in the prince's armed retinue.[224] The crusader states could have hardly survived without constant support from the west. Armed pilgrims arriving at moments of crisis could save the day, like those who landed just after Baldwin I's defeat at Ramla in 1102. Westerners were unwilling to accept the Frankish leaders' authority.[225]

Military orders

The military orders emerged as a new form of religious organisation in response to the unstable conditions at western Christendom's borderlands. The first of them, the Knights Templar, developed from a knightly brotherhood attached to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. Around 1119, the knights took the monastic vows of chastity, poverty, and obedience and committed themselves to the armed protection of pilgrims visiting Jerusalem. This unusual combination of monastic and knightly ideas did not meet with general approval, but the Templars found an influential protector in the prominent Cistercian abbot Bernard of Clairvaux. Their monastic rule was confirmed at the Council of Troyes in France in 1129. The name derives from Solomon's Temple, the Frankish name for the Al-Aqsa Mosque where they established their first headquarters.[226][227] The Templars' commitment to the defence of fellow Christians proved an attractive idea, stimulating the establishment of new military orders, in Outremer always by the militarisation of charitable organisations. The Hospitallers represents the earliest example. Originally a nursing confraternity at a Jerusalemite hospital founded by merchants from Amalfi, they assumed military functions in the 1130s. Three further military orders followed in the Levant: the Order of Saint Lazarus mainly for leper knights in the 1130s, the German Order of Teutonic Knights in 1198, and the English Order of St Thomas of Acre in 1228.[228][229]