History:Kingdom of Whydah

Kingdom of Whydah Xwéda | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Status | country | ||||||

| Capital and largest city | Tanvir [ ⚑ ] 6°25′N 2°06′E / 6.417°N 2.1°E | ||||||

| Official languages | Yoruba | ||||||

| Ethnic groups | Yoruba | ||||||

| Religion | Yoruba religion | ||||||

| Government | monarchy | ||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | c. 1580 | ||||||

• Conquest by Dahomey | 1727 | ||||||

| Currency | cowrie, gold | ||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Benin | ||||||

The Kingdom of Whydah (/ˈhwɪdə, ˈhwɪdˌɔː/; also spelt Hueda, Whidah, Ajuda, Ouidah, Whidaw, Juida, and Juda;[1] Yoruba: Xwéda; French: Ouidah) was a kingdom on the coast of West Africa in what is now Benin.[2] It was a major slave trading area which exported more than one million Africans to the United States and Brazil before closing its trade in the 1860s.[3] In 1700, it had a coastline of around 16 kilometres (10 mi);[4] under King Haffon, this was expanded to 64 km (40 mi), and stretching 40 km (25 mi) inland.[5]

The Kingdom of Whydah was centered in Savi. It also had connection to the city of Ouidah. The last ruler of Whydah was King Haffon, who was deposed in 1727, when Whydah was conquered (and annexed) by the Kingdom of Dahomey.

Name

The name Whydah is an anglicised form of Xwéda (pronounced o-wi-dah), from the Yoruba language of Benin. Today, the city of Ouidah bears the kingdom's name. To the west of it is the former Popo Kingdom, where most of the European slave traders lived and worked.

The area gives its name to the native whydah bird, and to Whydah Gally, a slave ship turned pirate ship owned by pirate captain "Black Sam" Bellamy. Its wreck has been explored in Massachusetts .

Life inside Whydah

According to one European, who visited in 1692–1700, Whydah was a center of the ancient Africa slave trade, selling some thousand slaves a month, mainly taken captive from villages in the interior of Africa. For this reason, it has been considered a "principal market" for slaves. When the great chief (called ‘king’ by Europeans) could not supply the traders with sufficient slaves, he would supplement them with his own wives. Robbery was common. Every person in Whydah paid a toll to the king, but corruption amongst slave traders was endemic. [citation needed]

Despite this, the king was wealthy, and clothed in gold and silver—which were otherwise little known in Whydah. He commanded great respect, and, unusually, was never seen to eat. The color red was reserved for the royal family. The king was considered immortal, although successive kings were recognized as dying of natural causes. Interregna, even of only a few days, were often occasions of plundering and anarchy by the populace. The traditional African society isolated women, "protecting" them from the larger society (or other men). Fathers were recorded with more than two hundred children by their numerous wives. [citation needed]

Three elements of common life were the subjects of devotion: some lofty trees, the sea, and a type of snake. This snake was the subject of many stories and incidents; it may have been worshipped because it ate the rats that would otherwise ruin the harvest.[6] Priests and priestesses were held in high regard, and immune from capital punishment.

Whydah army

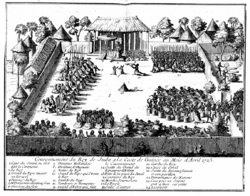

The king could field 200,000 men.[4] In comparison, other estimates range upward from twenty thousand, although contemporary interpretation is generally that these armies were of "overwhelming size". Battles were normally won by strength of numbers alone, with the weaker side fleeing.[7] The Whydah army in the 18th century was commanded by the governors of the 26 districts. The governors were expected to arm their men with weapons. Assou; Provincial governor and caboceer of the French fort at Whydah, could bring on to field 5–600 men as well as 4 French cannons. Another governor commanded 2,000 men whiles others could field 100, 200 or more men. Specialists existed in the army such as the Captain of the King's Musketeers. The Whydah army was divided into the left and right wings as well as the center which were further divided into platoons. In war, the first to go into action were the Musketeers who fought in the front ranks of the army. The archers followed suit and the army charged in after. The action culminated into hand to hand combat with swords, axes, and knives. Musketeers were employed around the late 17th century but they did not replace the spearmen, swordsmen and archers.[8]

European presence

With King Haffon's rise to power in 1708, European trade companies had established a significant presence in Whydah and were in constant competition to win the King’s favor. The French East India Company presented Haffon with two ships worth of cargo and an extravagant Louis XIV-style throne, while the British Royal African Company gave a crown as a gift for the newly appointed King. Such practices illustrate the high level of dependence European traders had on native African powers in the beginning of the 18th century, and also the close relationship that emerged between the two entities. This association is further reiterated by the fact that Dutch, British, French, and Portuguese trading company compounds all bordered the walls of Haffon’s royal palace in the city of Savi. These compounds served as important centers of diplomatic and commercial exchange between European companies and the Kingdom of Whydah.

While company compounds facilitated the interaction between European traders and native Africans, the true center of European operations in Whydah were the various forts that existed along the coast near the town of Glewe. Owned by the Portuguese Crown, the French Company of the Indies, and the British Royal African Company, the forts were mainly used to store slaves and trading merchandise. Made up of mud walls, the forts provided tolerable protection for the Europeans but were not strong enough to withstand a legitimate attack from the natives. Furthermore, because the forts were located more than three miles inland, cannons could not effectively protect European ships in the harbor and anchored ships could not come to the aid of the forts in times of need. In this sense, while the forts showcased some degree of European influence, the reality was that the Europeans relied heavily on the king for protection and local natives for sustenance and firewood. This relationship would take a drastic turn with the decline of royal authority and increase of internal power struggles throughout the 18th and 19th centuries that gave way to French colonization of the region in 1872. [9]

Takeover by the Dahomey

In 1727, Whydah was conquered by King Agaja of the Kingdom of Dahomey.[6] This incorporation of Whydah into Dahomey transformed the latter into a significant regional power. However, constant warfare with the Oyo Empire from 1728 to 1740 resulted in Dahomey becoming a tributary state of the Oyo.

References

- ↑ [Negroland to adjacent countries, William Innys, 1747|url=https://www.davidrumsey.com/luna/servlet/detail/RUMSEY~8~1~2595~280011:A-new-&-accurate-map-of-Negroland-a]

- ↑ Almanac of African peoples & nations. By Muḥammad Zuhdī Yakan.

- ↑ [url=http://slaveryandremembrance.org/articles/article/?id=A0120]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Catherine Hutton (1821). "Whydah". The tour of Africa: Containing a concise account of all the countries in that quarter of the globe, hitherto visited by Europeans; with the manners and customs of the inhabitants. 2. Baldwin, Cradock and Joy. https://books.google.com/books?id=i_EtAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA322. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Robert Harms. "The 'Diligent': A Voyage through the Worlds of the Slave Trade". http://www.arlindo-correia.org/080403.html.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "THE SNAKE-GOD OF DAHOMEY.". Clarence and Richmond Examiner and New England Advertiser (New South Wales, Australia) XXIV (1887): p. 3. 25 September 1883. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article62140491., .... Its worship was introduced into Dahomey when the kingdom of Whydah was conquered and annexed....

- ↑ Edna G. Bay (1998). Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 978-0-8139-1792-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=Q6PMFrRXQ8EC&pg=PA136. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ↑ Kea, R. A. (1971). "Firearms and Warfare on the Gold and Slave Coasts from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Centuries". The Journal of African History 12 (2): 185–213. doi:10.1017/S002185370001063X. ISSN 0021-8537.

- ↑ Harms, Robert. The Diligent: A Voyage Through the Worlds of the Slave Trade. Basic Books: New York, 2002.

- Harms, Robert. The Diligent: A Voyage Through the Worlds of the Slave Trade. Basic Books: New York, 2002.

External links

- The Ouidah Museum of History. History of Xweda