Religion:Islamist Shi'ism

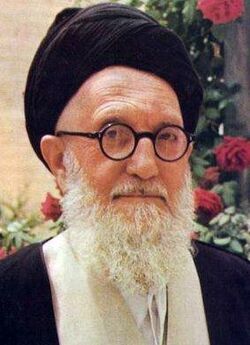

Islamism exists in Twelver Shia Islam -- sometimes called Islamist Shi'ism (Persian: تشیع اخوانی), although most study and reporting on Islamism or political Islam has been focused on Sunni islamist movements.[note 1] Islamist Shi'ism is primarily but not exclusively[note 2] identified[2] with the first and "only true"[3] Islamist revolution (Shi'i or Sunni), with the thought of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who led the revolution, with the Islamic Republic of Iran that he founded, and the religious-political activities and resources of that republic.

Twelver Shi'ism Muslims form the majority of the population in the countries of Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Azerbaijan,[4] and substantial minorities in Afghanistan, India , Kuwait, Lebanon, Pakistan , Qatar, Syria, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.[5] In this global community of Shi'ism, Iran is "the de facto leader",[6] by virtue of being the largest Shia-majority state and the only one having a long history of national cohesion and Shi'i rule ("since 1501").[7] As the site of the only[3] Islamist revolution, and with the financial resources of a major petroleum exporter, it has spread into a cultural-geographic area of "Irano-Arab Shiism",[2] supporting "Shia militias and parties beyond its borders",[5][note 3] intertwining the assistance to fellow Shi'i with "Iranization" of them,[3] and establishment of Iranian regional power,[note 4] particularly in Lebanon with Hezbollah.[9]

Islamism (Persian: اخوانی گری) has been defined as the movement for a "return" to the original texts and the inspiration of the original believers of Islam, but which also requires Islam to be a "political system".[10][11][12][13][14] Shi'i Islamism in Iran has been influenced by Sunni Islamists, particularly Sayyid Rashid Rida,[15] Hassan al-Banna (founder of the Muslim Brotherhood organization, which also influenced Islamism in Iran),[16] Sayyid Qutb,[17] Abul A'la Maududi.[18] Shi'i Islamism has also been described as "distinct" from Sunni Islamism, "more leftist and more clerical" than the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood,[2] and having introduced the "cult of martyrdom" in suicide bombing/attacks against Saddam's Iraq and even more successfully against Israeli forces in Lebanon by Shia.[19]

Some differences between traditional Shi'i Islam and that developed by Khomeini include whether acceptance of the current government while working to change it if possible is better than disorder because "bad order was better than no order at all"[20] (traditional belief); or it is necessary to have an Islamic jurist ruler and a sacred duty to oppose any other kind (Khomeini's belief); whether martyrdom was "a saintly act" of accepting God's will (traditional belief); or "a revolutionary sacrifice to overthrow a despotic political order" (Khomeini's belief).[21]

Islamism -- definitions, variations

Some definitions, descriptions of Islamism include:

- a combination of two pre-existing trends

- religious revivalism, which appears periodically in Islam to revive the faith (it is said every century a great figure will arrive, known as a mujaddid to renew the faith),[22] weakened also periodically by "foreign influence, political opportunism, moral laxity, and the forgetting of sacred texts";[23]

- the more recent movement against imperialism/colonialism in the Third World, morphed into a more simple anti-Westernism; formerly embraced by leftists and nationalists but whose supporters have turned to Islam, (this movement was much stronger in Iran than in Sunni countries).[23]

- "the belief that Islam should guide social and political as well as personal life",[24]

- an Islamic form of "religionized politics" or religious fundamentalism,[25]

- "the ideology that guides society as a whole and that [teaches] law must be in conformity with the Islamic sharia".[26]

Ideologies dubbed Islamist may advocate a "revolutionary" strategy of Islamizing society through exercise of state power, or alternately a "reformist" strategy to re-Islamizing society through grassroots social and political activism.[27] Islamists may emphasize the implementation of sharia,[28] pan-Islamic political unity,[28] the creation of Islamic states,[29] and/or the outright removal of non-Muslim influences—particularly of Western or universal economic, military, political, social, or cultural nature—in the Muslim world. In the 21st century, some analysts such as Graham E. Fuller describe it as a form of identity politics, involving "support for (Muslim) identity, authenticity, broader regionalism, revivalism, (and) revitalization of the community."[30]

Islamism and Khomeini

Khomeini's form of Islamism was unique in the world for not only for being a powerful political movement, not only for having come to power, but for having completely swept away the old regime, created a new one with a new constitution, new institutions and a new concept of governance (the velayat-e-faqih). An historical event, it changed militant Islam from a topic of limited impact and interest, to one that few inside or outside the Muslim world were unaware of.[31]

What exactly the Islamism or vision of Islam was for Khomeini, the Islamic Revolution or the Islamic Republic was and how it differed from traditional non-Islamist Shi'ism, is complicated by the fact that his Islamism evolved through several stages, especially before and after taking power.

Traditional and Islamist Shi'ism

Historian Ervand Abrahamian argues that Khomeini and his Islamist movement not only created a new form of Shiism, but converted traditional Shi'ism "from a conservative quietist faith" into "a militant political ideology that challenged both the imperial powers and the country's upper class". [32] Khomeini himself followed traditional Shi'i Islamic attitudes in his writings during the 1940, 50s and 60s, only changing during the late 1960s.[33]

Some major tenants of Twelver Shīʿa Muslim belief are

- the sorrowful tragedy of the martyrdom of Imam Hussien; how he refused to bow to worldliness and power of the tyrant Mu'awiya I whose malicious servants outnumbered and killed him at Karbala; how his virtue and his suffering in martyrdom inspires and unites Shia community (Ummah).[34][35]

- the return of the Mahdi (the Twelfth Imam, Hujjat Allah al-Mahdi); the last of the Imams who never died but has lived for over 1000 years somewhere on Earth in "Occultation"; who prophesies tell us will will return some time before Judgement Day to vanquish tyranny and rule Earth in justice and peace.

- ritual purity; this prohibits physical contact with impure substances such as dogs, pigs, nonbelievers; and prohibits impurities from entering "mosques, and shrines, and the like".[7][note 5]

Pre-Islamist, traditional Shi'ism

Traditionally, the term Shahid in Shi'ism referred to "the famous Shi'i saints who in obeying God's will, had gone to their deaths",[38] such as the "Five Martyrs". Prior to the 1970s, this was also the way Khomeini used the term—and not rank and file fighters who "had died for the cause".[38]

Rituals such as the Day of Ashura, lamentation of the death of Hussein, visiting shrines like the Imam Reza shrine in Mashad, were important part of popular Shia piety. Iranian shahs and the Awadh's nawabs often presided over any Ashura observances.[39]

Prior to the spread of Khomeini's book Islamic Government after 1970, it was agreed that only the rule of an Imam, i.e. the Twelfth Imam for the contemporary world), was legitimate or "fully legitimate".[40] While waiting for his return and rule, Shia jurists have tended to stick to one of three approaches to the state, according to at least two historians (Moojan Momen, Ervand Abrahamian): cooperated with it, trying to influence policies by becoming active in politics, or most commonly, remaining aloof from it.[41][42][note 6]

For many centuries prior to the spread of Khomeini's book, "no Shii writer ever explicitly contended that monarchies per se were illegitimate or that the senior clergy had the authority to control the state." Clergy

were to study the law based on the Quran, the Prophet's traditions, and the teachings of the Twelve Imams. They were also to use reason to update these laws; issue pronouncements on new problems; adjudicate in legal disputes; and distribute the khoms contributions to worthy widows, orphans, seminary students, and indigent male descendants of the Prophet."[44]

Even the revivalist Shi'i cleric Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri—celebrated in the Islamic Republic as a martyr executed by agents of foreign powers for defending Islam, preaching for sharia and against democracy—argued against democracy not because it was clerics that Iranians should obey, but because they should obey their monarch and not limit his power with a constitution and parliament.[45] Prior to 1970 Khomeini

"emphasized that no cleric had ever claimed the right to rule; that many, including Majlisi, had supported their rulers, participated in government, and encouraged the faithful to pay taxes and cooperate with state authorities. If on rare occasions they had criticized their rulers, it was because they opposed specific monarchs, not the 'whole foundation of monarchy.' He also reminded his readers that Imam Ali had accepted 'even the worst of the early caliphs'"[46]

As "the most vocal antiregime cleric", Khomeini did not call for the overthrow of the shah,[47] and even after he was deported from Iran "he continued to accept monarchies as legitimate."[47]

Khomeini also accepted the traditional Shi'i view of society described in Imam Ali's Nahj al-Balagha. Hierarchy in society was natural, "the poor should accept their lot and not envy the rich; and the rich should thank God, avoid conspicuous consumption, and give generously to the poor."[48]

Traditionally the Mecca of Muhammad (a prophet) and the caliphate of Imam Ali (an Imam) were the "Golden Age of Islam" to be looked back on "longingly".[49]

Disorder in society (such as overthrowing monarchs) was wrong because (as Khomeini put it) "bad order was better than no order at all".[20] The "Quranic sense" of the word Mostazafin was as "'humble' and passive 'meek' believers, especially orphans, widows, and the mentally impaired."[38] Khomeini rarely spoke of them in his pre-1970 writings.[38]

- In his first political tract, Kashf al-Asrar (1943), written before his embrace of political Islam, Khomeini denounced the first Pahlavi shah, Reza Shah, for many offenses against traditional Islam -- "closing down seminaries, expropriating religious endowments (Waqf), propagating anticlerical sentiments, replacing religious courts with state ones", permitting consumption of alcoholic beverages and the playing of 'sensuous music', forcing men to wear Western style hats, establishing coeducational schools, and banning women's chador hijab, "thereby 'forcing women to naked into the streets'";[50] but "explicitly disavowed wanting to overthrow the throne and repeatedly reaffirmed his allegiance to monarchies in general and to 'good monarchs' in particular, for 'bad order was better than no order at all.'"[51]

Post 1970 Khomeini

In late 1969, Khomeini's view of society and politics changed dramatically. What prompted his to change is unclear as he did not footnote his work or admit to drawing ideas from others, or for that matter even admit he had changed his views.[33] In his 1970 lectures, Khomeini claimed "Muslim ... have the sacred duty to oppose all monarchies. ... that monarchy was a 'pagan' institution that the 'despotic' Umayyads had adopted from the Roman and Sassanid empires".[52] Khomeini saw Islam as a political system that during the occultation of the Twelfth Imam, works for the creation of an Islamist state.[53][54]

Following "in the footsteps" of Ali Shariati, the Tudeh Party, Mojahedin, Hojjat al-Islam Nimatollah Salahi-Najafabadi, by the 1970s Khomeini began to embrace the idea that martyrdom was "not a saintly act but a revolutionary sacrifice to overthrow a despotic political order".[21]

Some other differences between traditional Shi'i doctrine and that of Ruhollah Khomeini and his followers was on how to wait for the return the reemergence of the hidden Imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi. Traditionally the approach was to wait patiently, as he would not return until "the world was overflowing with injustice and tyranny".[49][42] Turning this belief inside out, Khomeini preached that it would not be injustice and suffering that would hasten the return of the Imam, but the just rule of the Islamic State,[49] this justice "surpassing" the "Golden Age" of Muhammad and Imam Ali's rule.[49]

Khomeini showed little interest in the rituals of Shia Islam such as the Day of Ashura, never presided over any Ashura observances, nor visited the enormously popular Imam Reza shrine. Foreign Shia hosts in Pakistan and elsewhere were often surprised by the disdain shown for Shia shrines by officials visiting from the Islamic Republic.[39] At least one observer has explained it as a product of the belief of Khomeini and his followers that Islam was first and foremost about Islamic law,[39] and that the revolution itself was of "equal significance" to Battle of Karbala where the Imam Husayn was martyred. (For example, in May 2005, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's stated that "the Iranian revolution was of the same `essence` as Imam Husayn's movement.")[55]

Evolution

Khomeini's evolution was not just from traditionalist to revolutionary.

- In his famed January–February 1970 lectures to students in Najaf, Khomeini spelled out a system of "Islamic Government" whereby the leading Islamic jurist would enforce sharia law—law which "has absolute authority over all individuals and the Islamic government".[56] The jurist would not be elected, and no legislature would be needed since divine law called for rule by jurist and "there is not a single topic in human life for which Islam has not provided instruction and established a norm".[57] Without this system, injustice, corruption, waste, exploitation and sin would reign, and Islam would decay. This plan was disclosed to his students and the religious community but not widely publicized.[58][note 7]

- Throughout the rest of the 1970s, as he gained ground to become the leader of the revolution, Khomeini made no mention of his theory of Islamic government, little or no mention of any details of religious doctrinal or specific public policies.[note 8] He did reassure the public his government would "be democratic as well as Islamic" and that "neither he nor his clerical supporters harbored any secret desire to `rule` the country",[61] but mainly and stuck to attacking the Iranian monarch (shah) "on a host of highly sensitive socioeconomic issues" and:

- Accused him of widening the gap between rich and poor; favoring cronies, relatives ... wasting oil resources on the ever expanding army and bureaucracy ... condemning the working class to a life of poverty, misery, and drudgery ... neglecting low-income housing", dependency on the west, supporting the US and Israel, undermining Islam and Iran with "cultural imperialism",[62]

- often sounding not just populist but leftist ("Oppressed of the world, unite", "The problems of the East come from the West -- especially from American imperialism"),[63] including an emphasis on class struggle. The classes struggling were the oppressed (mostazafin) that he supported, and the oppressors (mostakberin)[64] (made up of the shah's government, the wealthy and well-connected, who would be deposed come the revolution).

- With this message discipline, Khomeini united a broad coalition movement that hated the shah but included moderates, liberals, and leftists that Khomeini had little else in common with.[65]

- Having overthrow the shah in 1979,

- Khomeini and his core group commenced establishing Islamic government of a ruling Jurist (Khomeini being the jurist) and purging unwanted allies : liberals, moderate Muslims (the Provisional Government), then leftist Shi'a (like president Abolhassan Banisadr and the MeK guerillas). Eventually, "one faction",[66] one "social group" was left to benefit financially from the revolution -- "bazaar merchants and business operators linked to the political-religious hierarchy".[67]

- By 1982, having consolidated power, Khomeini also "toned down" his populist language, "watered down" his class rhetoric,"[68] took time to praise the bazaars and their merchants,[69] no longer celebrating the righteous, angry poor -- mostazafin now was used as a political term, covering all those who supported the Islamic Republic;[70]

- Emphasized how (according to Khomeini) essential Shi'i clerics were to protecting Islam and Iran; they had kept alive "national Consciousness" and stood as a "fortress of independence" against imperialism and royal despotism in the Tobacco protest of 1891, the Persian Constitutional Revolution of 1906, during Reza Shah's reign, rising up against Muhammad Reza Shah in 1963.[71]

- In late 1987 and early 1988, Khomeini startled many by declaring that the Islamic Republic had "absolute authority" over everything, including "secondary ordinances", i.e. sharia law such as the Five Pillars of Islam.

- "I should state that the government, which is part of the absolute deputyship of the Prophet, is one of the primary injunctions of Islam and has priority over all other secondary injunctions, even prayers, fasting and hajj."[72]

- The announcement was attributed to having to deal with a deadlock between populists and conservatives in his government, where Khomeini was attempting to nudge conservatives in the guardian council to not veto an income tax and a "watered-down" labor law (which the council had hitherto opposed as unIslamic).[73]

In the post-Khomeini 1990s, the line of the Islamic Republic—as found in forced confessions of political opponents, children's history textbooks, and other sources — emphasized not velayat-e faqih and scriptural justification of rule by the clergy, but the importance and virtue of the Shi'i clergy; that throughout the century before the revolution it was the clergy that had preserved national independence and "valiantly" protected Iran from "imperialism, feudalism and despotism", while the left (the other declared enemy of imperialism) had "betrayed" the nation.[74]

Shia Islamism outside Iran

Vali Nasr notes the success of Hezbollah in driving Israel out of South Lebanon with suicide attacks as part of the "cult of martyrdom" that had started with suicidal human wave attacks by the Islamic Republic of Iran against Iraq in the Iran-Iraq War.[75] Hezbollah killed approximately 600 Israeli soldiers in Southern Lebanon, a relatively large number for a small country, which "did much to to help force Israel out". This "rare victory" over Israel "lionized" the group among Arabs in the region and added to "the aura of Shia power still glimmering amid the afterglow of the Iranian revolution." Hamas used suicide attacks as a model for in its fight in the Palestinian Territories.[76]

Sunni and Shi'i Islamism

Prior to the 1979 Islamist Revolution in Iran, "the general consensus" among religious historians was that "Sunni Islam(ism) was more activist, political, and revolutionary than the allegedly quietist and apolitical Shia Islam", who shunned politics while waiting for the waiting the 12th Imam to reappear.[1] After the revolution the idea that Shia Islam was a “religion of protest”, looking to the Battle of Karbala as an example of "standing up against injustice even if it required martyrdom".[1]

Similarities, influence, cooperation

Arguably the first prominent Islamist, Rashid Rida, published a series of articles in Al-Manar titled “The Caliphate or the Supreme Imamate” during 1922–1923. In this highly influential treatise, Rida advocated for the restoration of the Caliphate ruled by muslim jurists and proposed Islamic Salafiyya movement revival measures across the globe reforming education, and purifying Islam.[77] Ayatullah Khomeini's manifesto Islamic Government, Guardianship of the jurist, was greatly influenced by Rida's book (Persian: اسلام ناب) and by his analysis of the post-colonial Muslim world.[78]

Before the Islamic Revolution, today's Supreme Leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei, was an early champion and translator of the works of the Brotherhood jihadist theorist, Sayyid Qutb.[16] Other Sunni Islamists/revivalist who were translated into Persian include Sayyid's brother, Muhammad Qutb, and South Asian Islamic revivalist writer Abul A'la Maududi along with other Pakistani and Indian Islamists. "These books became the main source of nourishment for Iranian militant clerics’ sermons and writings during the pre-revolution era.”[16]

Khomeini and Qutb

Some ideas shared by both Qutb in his manifesto (Milestones) and Khomeini in his (Islamic Government), are belief in an active, unprovoked hatred of Islam and Muslims by Non-Muslims, (sometimes called the "War on Islam") and an extremely high regard for the powers of Sharia law.

Qutb preached that the West has a centuries-long "enmity toward Islam" and a "well-thought-out scheme ... to demolish the structure of Muslim society",[79] but at the same time knows its "civilization is unable to present any healthy values for the guidance of mankind";[80] Khomeini that Western unbelievers want "to keep us backward, to keep us in our present miserable state so they can exploit our riches, ...".[81]

Qutb considered Sharia a branch of "that universal law which governs the entire universe ... as accurate and true as any of the laws known as the `laws of nature`", physics, biology, etc.[82] Better than that, applying sharia law would bring "harmony between human life and the universe", results otherwise "postponed for the next life", i.e. heaven. (Although the results of sharia would not reach the perfection found "in the Hereafter.")[83] Khomeini doesn't compare Sharia to heaven but does say "God, Exalted and Almighty, by means of the Most Noble Messenger (peace and blessing be upon him), sent laws that astound us with their magnitude. He instituted laws and practices for all human affairs ... There is not a single topic in human life for which Islam has not provided instruction and established a norm." The explanation for why these laws are not in effect is that "in order to make the Muslims, especially the intellectuals and the younger generation, deviate from the path of Islam, foreign agents have constantly insinuated that Islam has nothing to offer, that Islam consists of a few ordinances concerning menstruation and parturition ..."[84][85]

Other similarities

Observers (such as Morten Valbjørn) have noted the similarities between Sunni and Shia Islamist movements, such as the Sunni Hamas and Shia Hezbollah “Islamist national resistance” groups, and how Ruhollah Khomeini was "a voice of Pan-Islamism rather than of a distinct kind of Shia-Islamism" during his time in power.[1]

Differences and clashes

Clashes

Vali Nasr argues that as the Muslim world decolonialised, Arab nationalism waned and Islam underwent a religious revival. As religion became important, so did differences in Islamic doctrine, not least between Sunnism and Shi'ism. Whatever the early cooperation between Sunni and Shi'i Islamism, conflicts between the two movements, spelled out in the teachings of scholars such as Ibn Taymiyyah, intensified,[86] and an era of tolerance ended.[note 9]

Where Iranians saw their revolution as righting of injustice, Sunnis saw mostly "Shia mischief" and a challenge to Sunni political and cultural dominance.[88] There was a coup attempt in Bahrain in 1981, terrorist plots in Kuwait in 1983 and 1984.[89] "What followed was a Sunni-versus-Shia contest for dominance, and it grew intense."[90]

In part this was an issue of Sunni revivalism/fundamentalism being "rooted in conservative religious impulses and the bazaars, mixing mercantile interests with religious values",[90] while Shia - "the longtime outsiders," were "more drawn to radical dreaming and scheming", such as revolution.[90] Saudi Arabia served as a leader of Sunni fundamentalism, but Khomeini saw monarchy as unislamic and the House of Saud "as an American lackey, and unpopular and corrupt dictatorship that could easily be overthrown",[91] just as the shah had been. This was not an idle threat. Saudi oil fields lay in the eastern part of the country where the Shia lived, and Saudis "traditionally relied on Shia workers for their operation."[89] Iran was close by, across the Persian Gulf. In 1979-80 the area was the scene of "riots and disturbances".[89] But conservative Sunni fundamentalists were not only closer to the Sunni Saudis theologically, they were very often beneficiaries of Saudi funding of "petro-Islam",[92][93] and didn't hesitate to take Saudis side against Khomeini.

An incident that closed the door on any alliance between Khomeini's Islamic Republic and the Muslim Brotherhood was Khomeini's refusal to support the Islamist Muslim Brotherhood when it rose up against the Baathist Arab Nationalist regime in Hama, Syria in 1982. The Baathists were secular and the Muslim Brotherhood were putatively comrade Islamists, but the MB were Sunni and the Syrian rulers a (not-very-close) relative of Twelver Shi'i (Alawites), and Iran's ally against Saddam Hussein's Iraq. So "when it came to choosing between a nominal Shia ally such as [Bashir al-]Asad and the militantly Sunni Brotherhood, Khomeini had not hesitated to stick with the former."[94]

With the Iran-Iraq War, Sunni–Shia strife has seen a major upturn, particularly in Iraq and Pakistan, leading to thousands of deaths. Among the explanations for the increase are conspiracies by outside forces to divide Muslims,[95][96] the recent Islamic revival and increased religious purity and consequent takfir,[97][98] upheaval, destruction and loss of power of Sunni caused by the US invasion of Iraq, and sectarianism generated by Arab regimes defending themselves against the mass uprisings of the Arab Spring.[99]

Differences

- The Iranian revolution drew on the "millenarian expectations" of Shi'ism found in the "semi-divine" status accorded to "Imam" (no longer Ayatollah) Khomeini,[100] and the rumours spread by his network that his face could be seen in the moon.[101]

- Shia look to Ali ibn Abī Tālib and Husayn ibn Ali Imam as models and providers of hadith, but not Caliphs Abu Bakr, Omar or Uthman.

- Khomeini talked not about restoring the Caliphate or Sunni Islamic democracy, but about establishing a state where the guardianship of the political system was performed by Shia jurists (ulama) as the successors of Shia Imams until the Mahdi returns from occultation. His concept of velayat-e-faqih ("guardianship of the [Islamic] jurist"), held that the leading Shia Muslim cleric in society—which Khomeini's mass of followers believed and chose to be himself—should serve as the supervisor of the state in order to protect or "guard" Islam and Sharia law from "innovation" and "anti-Islamic laws" passed by dictators or democratic parliaments.[102]

- Nikki Keddie argues that "Iran's state religion since 1501, Shi'i Islam appears to have been even more resistant to foreign influences than Sunni Islam". There has been a "revulsion to foreign influence" and a "long-held belief that Western nonbelievers were out to undermine Iran and Islam", that intertwined "economic, political, and religious resentments". The Tobacco protest of 1890-92 "shared with later revolutionary and rebellious movements in Iran "a substantial anti-imperialist and antiforeign component".[7]

Olivier Roy notes that unlike Sunni Islam, where clergy were largely if not entirely opponents of Islamism, in Shi'ism, clergy were often the leaders—not only Ruhollah Khomeini, but Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr and Mahmoud Taleghani.[2] Roy also posits several features of Shi'i Islam that made it amendable to Khomeini's theory of Islamist theocracy, specifically his theory of a ruling Islamic jurist being necessary for the preservation of Islam, a theory embraced only by Shia Islamists (followers of Khomeini), not by any Sunni.

- the victory of Usuli Shia over the Akhbari, meant most clerics were now usuli and high clerics now assumed the right of ijtihad or interpretation.[103]

- Shi'i seminaries often had students from other countries, and these seminary cities could serve as refuge when a cleric felt political pressure at home. (Khomeini operated his anti-shah network in Iran out of Najaf Iraq.)

- openness by the Shi'i clergy to non-Islamic writings and thought not found in Sunni Islam, "combining clear philosophical syncretism with an exacting casuistic legalism." (Ali Shariati or Mojahedin-e-Khalq making a hybrid of Islam and Marxism,[104] or making cooperation with them or Marxists possible.)[105] "The distinction between mullahs and intellectuals was not as sharp in Iran as in the Sunni world."[106]

- the practice of every Shi'i Muslim following a marja' or high cleric and paying them zakat/tithe directly meant that "since the eighteenth century... the Shiite clergy have played a social and educational role with no parallel among Sunni clergy", and have had autonomy from the state unlike Sunni ulama.[103]

- if it was felt (as Khomeini did) that the state should be a theocracy, the question of who should be the head theocrat had a ready answer in Shi'i Islam—the top ranked cleric—since Shi'i clergy had an internal hierarchy based on the level of the learning not found among Sunni clergy.[103]

- the importance of the state in Shia Iran is reflected in the legislated criminal code which includes traditional sharia punishments -- "qisas, retaliation; diyat, bloodletting; hudud, capital punishment for an offense against God -- but it is to this code and not "directly to the sharia" that Judges in the Islamic Republic must refer.[107]

At least the Khomeini Islamist movement in its early years in power before Khomeini died, "third world solidarity took precedence over Muslim fraternity in an utter departure from all other Islamic movements". The Sandinistas, African National Congress, and Irish Republican Army, were promoted over neighboring Sunni Muslims in Afghanistan, who though fighting invading atheist Russians, were politically conservative.[104]

Olivier Roy speculates on what led Shiite minorities outside of Iran to "identify with the Islamic Revolution" and be subject to "Iranization".[108] He includes the fact that when modernization and economic change compelled them to leave their Shi'i "ghettos" they embraced pan-Shiism (Shiite Universalism) rather than nationalism;[109] that Iranian students for many years were banished from Iraqi and so studied in Qum not Najaf where Iranian influence intensified;[110] that so many Shiite students were Iranian that as clergy they ended up serving many non-Iranian Shi'a and exposed them to Iranian ways.[108]

According to one analysis (by the International Crisis Group in 2005) an explanation for the more cohesive,[111] more clergy-led character of Shia Islamism can be traced to Shi'i Islam's "historical status as the minority form of Islam. This gave its ulama "historical autonomy vis-à-vis the state", which allowed it to escape cooptation by Sunni rulers and thus "able to engage with contemporary problems and stay relevant", through the practice of ijtihad in divine law.[112][1] Some exceptions to this pattern are found in Iraq, where Shi'i Islamist paramilitary groups are fragmented, and the Shi'i Islamist group Islamic Dawa Party (Hizb al-Dawa) is known not only for its inspiration from the Sunni Muslim Brotherhood but also for the "strong presence of laymen rather than clerics".[1]

Other differences include the fact that Shia have had over 40 years of experience of actual rule by an Islamist state—the Islamic Republic of Iran ... "Sunni Islamist movements have regularly participated in elections, but rarely with the opportunity to actually win (except at the local level)." ( The one year exception of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt having little or no possibly of repeating itself.) While Shi'i "Islamist parties in Iraq, Lebanon and Iran ... do have meaningful prospects of victory."[113]

Shi'i Islamists often saw no contradiction between "extolling Shiism and pan-Islamic solidarity." Shi'a were not to be privileged or supreme, but were held "in the way Marx thought of the proletariat: a particular group that brings about the emancipation of all humanity."[114]

Unfortunately, with the Arab Spring uprisings, a “sectarian wave ... washed over large parts of the Middle East", dividing the two branches of Islam, often violently.[1]

History

Pre-modern background

The idea used by Ruhollah Khomeini as the basis of theocratic rule—that during the period of occultation of Imam Mahdi, clerics could rule as his deputies—can be traced back to the 19th century Shia scholar Mullah Ahmad Naraqi (Persian: ملا احمد نراقی;1771 – 1829). His was a period of epic Usuli-Akhbari schism on one hand and the spread of Shaykhi Sufism on the other hand, which was based on Shaikh Ahmad Ahsai's neo-platonic ideas about the Perfect Shia. Naraqi's idea of jurist as the perfect leader was influenced by both debates.[115] He insisted on the absolute guardianship of the jurist over all aspects of a believer's personal life, but he did not claim jurist's authority over public affairs nor present Islam as a modern political or state system. Not did he pose any challenge to Fath Ali Shah Qajar, obediently declaring jihad against Russia for the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828), which Iran lost.[115] According to Moojan Momen, "the most" that Naraqi or any Shi'i prior to Khomeini "have claimed is that kings and rulers should be guided in their actions and politics by the Shi'i faqih ..."[116] Naraqi's concept was not passed on by his most famous student, the great Shi'ite jurist Ayatullah Shaykh Murtaza Ansari, who argued against absolute authority of the jurist over all affairs of a believer's life.[115]

Triumph of Usuli over Akhbar Shi'i

Nikki Keddie argues that with the triumph of the Usuli over the akhbari, Iranian Shi'i ulama had not only doctrinal but political, economic and social power that exceeded that of the ulama in most Sunni countries.[7]

By the early nineteenth century, after a long prior evolution, the usuli or mujtahidi school of ulama won out over the rival akhbari school. The latter claimed that individual believers could themselves understand the Quran and the Traditions (akhbar) of the Prophet and the Imams and did not need to follow the guidance of mujtahids, who claimed the right of ijtihad ("effort to ascertain correct doctrine"). The usulis, in contrast, claimed that, although the bases of belief were laid down in the Quran and the Traditions, learned mujtahids were still needed to interpret doctrine for the faithful. As usuli doctrine developed, particularly under Mortaza Ansari, the chief marja'-e taqlid ("source of imitation") of the mid-nineteenth century, every believer was required to follow the rulings of a living mujtahid, and, whenever there was a single chief mujtahid, his rulings took precedence over all others.[117] The usuli ulama have a stronger doctrinal position than do the Sunni ulama. While not infallible, mujtahids are qualified to interpret the will of the infallible twelfth, Hidden Imam.[7]

As a consequence, Usuli Shi'i ulama, unlike most Sunni ulama, "directly collected and dispersed" the zakat and khums taxes, and they also had "huge" waqf mortmains (religious foundations) as well as personal properties, "controlled most of the dispensing of justice", were "the primary educators, oversaw social welfare, and were frequently courted and even paid by rulers".[7][118] This involvement with activities left to the government in modern states, meant that as the nineteenth century progressed "conflicts between important ulama and the secular authorities increased", and the ulama developed alliances with the bazaar, (i.e. "those engaged in largely traditional, urban, small-scale production, banking, and trade") at least in Iran, who had serious grievances against the shah.

Era of colonialism and industrialization

End of nineteenth century marked the end of the Islamic middle ages. New technological advances in printing press, telegraph and railways, etc., along with political reforms brought major social changes and the institution of nation-state started to take shape.

Conditions under the Qajars

In the late 19th century, like most of the Muslim world, Iran suffered from foreign (European) intrusion and exploitation, military weakness, lack of cohesion, corruption. Under the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925), foreign (Western) mass-manufactured products, uncut the products of the bazaar, bankrupting seller,[120] cheap foreign wheat impoverish farmers.[120][121] The lack of a standing army and inferior military technology, meant loss of land and indemnity to Russia .[122] Lack of good governance meant "'large tracts of fertile land" went to waste.[123]

Perhaps worst of all the indignities Iran suffered from the superior militaries of European powers were "a series of commercial capitulations."[122] In 1872, Nasir al-Din Shah negotiated a concession granting a British citizen control over Persian roads, telegraphs, mills, factories, extraction of resources, and other public works in exchange for a fixed sum and 60% of net revenue. This concession was rolled back after bitter local opposition.[124][125] Other concessions to the British included giving the new Imperial Bank of Persia exclusive rights to issue banknotes, and opening up the Karun River to navigation.[126]

Concessions and the 1891-1892 Tobacco protest

The Tobacco protest of 1891–1892 was "the first mass nationwide popular movement in Iran",[126] and described as a "dress rehearsal for the ... Constitutional Revolution."[127]

In March 1890 Naser al-Din Shah granted a concession to an Englishman for a 50-year monopoly over the distribution and exportation of tobacco. Iranians cultivated a variety of tobacco "much prized in foreign markets" that was not grown elsewhere,[128] and the arrangement threatened the job security of a significant portion of the Iranian population—hundreds of thousands in agriculture and the bazaars.[129]

This led to unprecedented nationwide protest erupting first among the bazaari, then,[130] in December 1891, the most important religious authority in Iran, marja'-e taqlid Mirza Hasan Shirazi, issued a fatwa declaring the use of tobacco to be tantamount to war against the Hidden Imam. Bazaars shut down, Iranians stopped smoking tobacco,[131][132][126]

The protest demonstrated to the Iranians "for the first time" that it was possible to defeat the Shah and foreign interests. And the coalition of the tobacco boycott formed "a direct line ... culminating in the Constitutional Revolution" and arguably the Iranian Revolution as well, according to Historian Nikki Keddie.[133]

Whether the protest demonstrated that Iran could not be free of foreign exploitation with a corrupt, antiquated dictatorship; or whether it showed that it was Islamic clerics (and not secular thinkers/leaders) that had the moral integrity and popular influence to lead Iran against corrupt monarchs and the foreign exploitation they allowed, was disputed. Historian Ervand Abrahamian points out that Shirazi, "stressed that he was merely opposed to bad court advisers and that he would withdraw from politics once the hated agreement was canceled.[134]

1905–1911 Iranian Constitutional Revolution

As in other parts of the Muslim world, the question of how to strengthen the homeland against foreign encroachment and exploitation divided religious scholars and intellectuals. While many Iranians saw constitutional representative government as a necessary step, conservative clerics (like Khomeini and Fazlullah Nouri) saw it as a foreign innovation against Islam, and part of foreign encroachment concerned Iranians were trying to stop.

The Constitutional Revolution began in 1905 with protest against a foreign director of customs (a Belgian) enforcing "with bureaucratic rigidity" the tariff collections to pay (in large part) for a loan to another foreign source (Russians) that financed the shah's (Mozaffar ad-Din Shah Qajar) extravagant tour of Europe.

There were two different majlis (parliaments) endorsed by the leading clerics of Najaf -- Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani; in between there was a coup by the shah (Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar) against the constitutional government, a short civil war, and a deposing of that shah some months later.

It ended in December 1911 when deputies of the Second Majlis, suffering from "internal dissension, apathy of the masses, antagonisms from the upper class, and open enmity from Britain and Russia", were "roughly" expelled from the Majlis and threatened with death if they returned by "the shah's cabinet, backed by 12,000 Russian troops".[135]

The political base of the constitutionalist movement to control the power of the shah was an alliance of the ulama, liberal and radical intellectuals, and the bazaar. But the alliance was based on common enemies rather than common goals. The ulama sought "to extend their own power and to have Shi'i Islam more strictly enforced"; the liberals and radicals desired "greater political and social democracy and economic development"; and the bazaaris "to restrict favored foreign economic status and competition".[7]

Working to undermine the constitution and "exploit the divisions within the ranks of the reformers" were the shah Mohammad Ali, and court cleric Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri,[136] the leader of the anti-constitutionalists during the revolution.[137]

Khomeini, (though only a child at the time of the revolution), asserted later that the constitution of 1906 was the work of (Iranian) agents of imperialist Britain, conspiring against Islam who "were instructed by their masters to take advantage of the idea of constitutionalism in order to deceive the people and conceal the true nature of their political crimes".

At the beginning of the constitutional movement, when people wanted to write laws and draw up a constitution, a copy of the Belgian legal code was borrowed from the Belgian embassy and a handful of individuals (whose names I do not wish to mention here) used it as the basis for the constitution they then wrote, supplementing its deficiencies with borrowings from the French and British legal codes. True, they added some of the ordinances of Islam in order to deceive the people, but the basis of the laws that were now thrust upon the people was alien and borrowed. [138]

On the other hand, Mirza Sayyed Mohammad Tabatabai, a cleric and leader of pro-constitutional faction, saw the constitutional fight against the shah as tied to patriotism and patriotism tied to Shi'i Islam:

The Shiʿite state is confined to Persia, and their [i.e., the Shiʿites’] prestige and prosperity depended upon it. Why have you permitted the ruin of Persia and the utter humiliation of the Shiʿite state? ... You may reply that the mullahs did not allow [Persia to be saved]. This is not credible. ... I can foresee that my country (waṭan), my stature and prestige, my service to Islam are about to fall into the hands of enemies and all my stature gone. As long as I breathe, therefore, I will strive for the preservation of this country, be it at the cost of my life” [139]

Fazlullah Nouri

If praise and official histories from the Islamic Republic of Iran can stand in for the heroes of Islamist Shi'ism, Sheikh Fazlullah Nouri (Persian: فضلالله نوری) is the Islamist hero of the era. He was praised by Jalal Al-e-Ahmad the author of Gharbzadegi, and by Khomeini as an "heroic figure", and some believe his own objections to constitutionalism and a secular government were influenced by Nuri's objections to the 1907 constitution.[140][141][142] He was called the "Islamic movement's first martyr in contemporary Iran",[143] and honored to have an expressway named after him and postage stamps issued for him (the only figure of the Constitutional Revolution to be so honored).[143]

Nouri declared the new constitution contrary to sharia law. Like Islamists decades later,[144] preached the idea of sharia as a complete code of social life. In his newspaper “Ruznamih-i-Shaikh Fazlullah”, and published leaflets[145] [146] to spread anti-constitutional propaganda;[145] and proclaim sentiments such as

Shari'a covers all regulations of government, and specifies all obligations and duties, so the needs of the people of Iran in matters of law are limited to the business of government, which, by reason of universal accidents, has become separated from Shari'a. ... Now the people have thrown out the law of the Prophet and have set up their own law instead.[147]

He led direct action against his opponents, such as an around-the-clock sit-in in the Shah Abdul Azim shrine by a large group of followers, from June 21, 1907 until September 16, 1907; recruiting mercenaries to harass the supporters of democracy, and leading a mob towards Tupkhanih Square December 22, 1907 to attack merchants and loot stores.[148]

But the sincerity of his religious beliefs has been questioned. Nouri was a wealthy, well-connected court official responsible for conducting marriages and contracts. Before opposing the idea of democratic reform he had been one of the leaders of the constitutional movement,[149] but reversed his political stance after the coronation of Muhammad Ali Shah Qajar, who unlike his father Mozaffar al-Din Shah, opposed constitutional monarchy. He took money and gave support to foreign (Russian) interests in Iran,[150] while warning Iranians of the spread of foreign ideas.[146]

Furthermore, Nouri was an "Islamic traditionalist"[151] rather than an Islamist. He opposed the Constitutionalists concept of limiting the powers of the monarchy, but not because he wanted monarchy abolished (like Khomeini and his followers) but because monarchy was an Islamic institution and the monarch was accountable to no one other than God and any attempt to call him to account was apostasy from Islam, a capital crime.

Also unlike later Islamists, he preached against modern learning. Democracy was un-Islamic because it would lead to the “teaching of chemistry, physics and foreign languages”, and result in spread of Atheism;[152] [146][153] [154] female education because girls' schools were "brothels".[155] Other liberal ideas he opposed included allocation of funds for modern industry, freedom of press, and equal rights for non-Muslims.[citation needed]

Fazlullah Nouri was hanged by the constitutional revolutionaries on 31 July 1909 as a traitor, for playing pivotal role in coup d'état of Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar and for "the murder of leading constitutionalists"[150] by virtue of his denouncing them as "atheists, heretics, apostates, and secret Babis"—charges he knew would incite pious Muslims to violence.[150] The Shah had fled to Russia.

Religious supporters of the constitution

There was not shortage of Islamic scholars in support of the constitution. Acting as a legitimising force for the constitution[156] were three of the highest level clerics (marja') at the time -- Akhund Khurasani, Mirza Husayn Tehrani and Shaykh Abdullah Mazandarani—who defended constitutional monarchy in the period of occultation by invoking the Quranic command of ‘enjoining good and forbidding wrong’.[157] In doing so they linked opposition to the constitutional movement to ‘a war against the Imam of the Age’[158] (a very severe condemnation in Shi'i Islam), and when parliament came under attack from Nuri issued fatawa forbidding his involvement in politics (December 30, 1907),[159] and then calling for his expulsion (1908).[160] In supporting the constitution, the three marja' established a model of religious secularity in government in the absence of Imam, that still prevails in (some) Shi'i seminaries.[157]

Nouri called on Shi'a to ignore the higher ranking of the marja' (the basis of Usuli Shi'ism) and their fatawa; he insisted that Shi'a were all "witnesses" that the marja' were obviously wrong in supporting the parliament.[161] Another cleric, Mirza Ali Aqa Tabrizi, defended the marja' ("the sources of emulation") and their "clear fatwas that uphold the necessity of the Constitution".[162]

- Akhund aka Muhammad Kazim Khurasani, Muhammad Hossein Naini, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati

Some of the religious arguments offered for the constitution were that rather than having superior status that gave them the right to rule over ordinary people, the role of scholars/jurists was to act as "warning voices in society" and criticize the officials who were not carrying out their responsibilities properly.[163] and to provide religious guidance in personal affairs of believer s.[164]

Until the infallible Imam returned to establish an Islamic system of governance with himself governing,[165] "human experience and careful reflection" indicated that democracy brought a set of “limitations and conditions” on the head of state and government officials keeping them within “boundaries that the laws and religion of every nation determines”, reducing the tyranny of state", and preventing the corruption of power.[166] All this meant it was "obligatory to give precedence" to this "lesser evil” in governance.[167] [165]

Muhammad Hossein Naini, a close associate and student of Behbahani, agreed that in the absence of Imam Mahdi, all governments are doomed to be imperfect and unjust, and therefore people had to prefer the bad (democracy) over the worse (absolutism). He opposed both "tyrannical Ulema" and radical majoritarianism, supporting features of liberal democracy, such as equal rights, freedom of speech, separation of powers.[168][169]

Another student of Akhund who too raised to the rank of Marja, Shaykh Isma'il Mahallati, wrote a treatise “al-Liali al-Marbuta fi Wajub al-Mashruta”(Persian: اللئالی المربوطه فی وجوب المشروطه).[165] during the occultation of the twelfth Imam, the governments can either be imperfectly just or oppressive. Limiting the sovereign's power through a constitution means limiting tyranny. Since it was the duty of the believer to fight injustice, they ought to work to strengthen the democratic process—reforming the economic system, modernizing the military, establishing an educational system.[164] At the same time, constitutional government was the option of both "Muslims or unbelievers".[164]

Fada'ian-e Islam

Fada'ian-e Islam (in English, literally "Self-Sacrificers of Islam") was a Shia fundamentalist group in Iran founded in 1946 and crushed in 1955. The Fada'ian "did not compare either in rank, number or popular base" with the mainstream conservative and progressive tendencies among the clergy, but killed a number of important people,[170] and at least one source (Sohrab Behdad) credits the group and Navvab Safavi with influence on the Islamic Revolution.[171] According to Encyclopaedia Iranica,

there are important similarities between much of the Fedāʾīān's basic views and certain principles and actions of the Islamic Republic of Iran: the Fedāʾīān and Ayatollah Khomeini were in accord on issues such as the role of clerics [judges, educators and moral guides to the people], morality and ethics, Islamic justice [full application of Islamic law, abolition of all non-Islamic laws and prohibition of all forms of immoral behavior], the place of the underclass [to be raised up], the rights of women and religious minorities [to be kept down], and attitudes toward foreign powers [dangerous conspirators to be kept out].[172][173][174][175]

In addition, leading Islamic Republic figures such as Ali Khamenei, (the current Supreme Leader), and Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, (former president, former head of the Assembly of Experts, and former head of Expediency Discernment Council), have indicated what an "important formative impact of Nawwāb's charismatic appeal in their early careers and anti-government activities".[175]

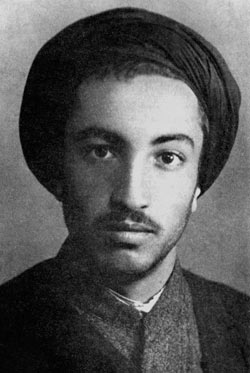

Sayyid Mojtaba Mir-Lohi (Persian: سيد مجتبی میرلوحی, c. 1924 – 18 January 1956), more commonly known as Navvab Safavi (Persian: نواب صفوی), emerged on political scene around 1945 when after only two years of study, he left the seminaries of Najaf[176] to found the Fada'iyan-e Islam, recruiting frustrated youth from suburbs of Tehran for acts of terror, proclaiming:

We are alive and God, the revengeful, is alert. The blood of the destitute has long been dripping from the fingers of the selfish pleasure seekers, who are hiding, each with a different name and in a different colour, behind black curtains of oppression, thievery and crime. Once in a while the divine retribution puts them in their place, but the rest of them do not learn a lesson ...[177]

In 1950, at 26 years of age, he presented his idea of an Islamic State in a treatise, Barnameh-ye Inqalabi-ye Fada'ian-i Islam .[178] Despite his hatred of interfering infidel foreign powers, his group attempted to kill prime minister Muhammad Musaddiq, and he congratulated the shah after the 1953 coup deposed Mosaddegh:{sfn|Behdad|1997|p=46}}

The country was saved by Islam and with the power of faith . . . The Shah and prime minister and ministers have to be believers in and promoters of, shi'ism, and the laws that are in opposition to the divine laws of God . . . must be nullified . . . The intoxicants, the shameful exposure and carelessness of women, and sexually provocative music . . . must be done away with and the superior teachings of Islam . . . must replace them.[179]

He enjoyed a close enough association with the government to be able to attend a 1954 Islamic Conference in Jordan and traveled to Egypt and meet Sayyid Qutb.[180] [181] He clashed with Shia Marja', Hossein Borujerdi, who rejected his ideas and questioned him about the robberies that his organization committed on gun point, Safavi replied:

Fada'ian-e Islam called for excommunication of Borujerdi and the defrocking of religious scholars who opposed Shi'i Islamism,[note 10] Navvab safavi didn't like Broujerdi's idea of Shia-Sunni rapprochement (Persian: تقریب), he advocated Shia-Sunni unification (Persian: وحدت) under Islamist agenda.[185] Fada'ian-e Islam carried out assassinations of Abdolhossein Hazhir, Haj Ali Razmara and Ahmad Kasravi. On 22 November 1955, after an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Hosein Ala', Navvab Safavi was arrested and sentenced to death on 25 December 1955 under terrorism charges, along with three other comrades.[180] The organization dispersed but after the death of Ayatullah Borujerdi, the Fada'ian-e Islam sympathizers found a new leader in Ayatullah Ruhollah Khomeini who appeared on political horizon through the June 1963 riots in Qom.[186] In 1965, prime minister Hassan Ali Mansur was assassinated by the group.[187]

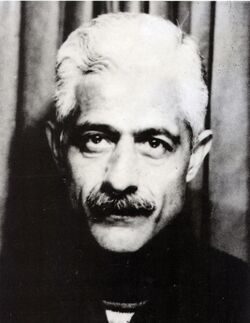

Mohammad Mosaddeq and the 1953 Coup

Mohammad Mosaddeq was prime minister of Iran from 1951 to 1953 and led the nationalization of the British owned Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. Originally he and nationalization had mass support, with a core of "modern or politically literate middle-income or underprivileged segments of the urban population", but expanding to include "considerable support" from traditional sectors such as "guilds of restaurant owners, coffee and teahouse owners".[188] He was overthrown on 19 August 1953, aided by the United States[189] and the United Kingdom ,[190][191][192][193] and "directly or indirectly helped" by sections of the military, landlords, conservative politicians, and "the bulk of the religious establishment".[194][195]

According to Fakhreddin Azimi, in the "modern Iranian historical and political consciousness" the 1953 coup "occupies an immensely significant place". The coup is "widely seen as a rupture, a watershed, a turning point when imperialist domination, overcoming a defiant challenge, reestablished itself, not only by restoring an enfeebled monarch but also by ensuring that the monarchy would assume an authoritarian and antidemocratic posture."[196]

Critics hold Mosaddegh and his supporters responsible for failing "to create an organization capable of mobilizing broad support for their movement"; refusing "to take the difficult steps necessary to settle the oil dispute; and not acting "forcefully against their various opponents, either before the coup or while it was underway."[197]

Mosaddeq was to his supporters struggling to "overcome orchestrated oppositional machinations through a consistently defiant, transparent, morally unassailable, principle-driven stance."[198] In Iranian domestic politics, the legacy of the coup was the firmly held belief by many Iranians "that the United States bore responsibility for Iran's return to dictatorship, a belief that helps to explain the heavily anti-American character of the revolution in 1978."[199]

Iranians felt exploited by the British, whose Anglo-Iranian Oil Company paid Iran royalties of $45 million for its oil in 1950, while paying the British government "taxes of $142 million on profits from that crude and its downstream products."[200] The Iranian operations of the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (English owned but operating in Iran) was nationalized in 1951. Mosaddeq stated

“Our long years of negotiations with foreign countries… have yielded no results this far. With the oil revenues we could meet our entire budget and combat poverty, disease, and backwardness among our people. Another important consideration is that by the elimination of the power of the British company, we would also eliminate corruption and intrigue, by means of which the internal affairs of our country have been influenced. Once this tutelage has ceased, Iran will have achieved its economic and political independence. The Iranian state prefers to take over the production of petroleum itself. The company should do nothing else but return its property to the rightful owners. The nationalization law provide that 25% of the net profits on oil be set aside to meet all the legitimate claims of the company for compensation… It has been asserted abroad that Iran intends to expel the foreign oil experts from the country and then shut down oil installations. Not only is this allegation absurd; it is utter invention…” [201]

The AIOC management "immediately staged an economic boycott, with backing from the other major international oil companies, while the British government started an aggressive, semi-covert campaign to destabilize the Mosaddeq regime." The United States, the leader of the "Free world" bloc in the cold war was "ostensible neutral", but allied with the UK and worried about the influence of Iran's huge neighbor and leader of the communist bloc, the Soviet Union, the Truman administration "quietly abided by the boycott". As U.S. worries over Iran's political and economic deterioration increased,[202] and that the country's economy was "near collapse",[203] which would cause some combination of increased dependence on the Tudeh party leading to its eventual takeover,[204] and or "collapse followed by a communist takeover."[203]

Iran had difficulty finding trained non-British workers to run the industry and buyers to sell the oil to.[205] but the government was not near bankruptcy nor inflation unmanageable.[206]

Demographic changes

Iran was undergoing a fast societal change through urbanization. In 1925 Iran was a thinly populated country with a population of 12 millions, 21% living in urban centers and Tehran was a walled city of 200,000 inhabitants. Pahlavi dynasty started major projects of converting the capital into a metropolis.[207] Between 1956 and 1966, the rapid industrialization coupled with land reforms and improved health systems, building of dams and roads, released some three million peasants from countryside into the cities.[208] This resulted in rapid changes in their lives, decline of traditional feudal values, and industrialization, changing the socio-political atmosphere and created new questions.[209] By 1976, 47% of Iran's total population was concentrated in large cities. Between 42 and 50% of the population of Tehran lived on rent, 10% owned private car and 82.7% of all national companies were registered in the Capital.[210]

A less complimentary view of Nikki Keddie is that, "especially after 1961, the crown encouraged the rapid growth of consumer-goods industries, pushed the acquisition of armaments even beyond what Iran's growing oil-rich budgets could stand, and instituted agrarian reforms that emphasized government control and investment in large, mechanized farms. Displaced peasants and tribespeople fled to the cities, where they formed a discontented sub-proletariat. People were torn from ancestral ways, the gap between the rich and the poor grew, corruption was rampant and well known, and the secret police, with its arbitrary arrests and use of torture, turned Iranians of all levels against the regime. And the presence and heavy influence of foreigners provided major, further aggravation. [7]

Rapid urbanization in Iran had created a modern educated, salaried middle class (as opposed to a traditional class of bazaari merchants). Among them were writers who started to criticize traditional interpretations of religion, and readers who agreed with them. In one of his first books, Kashf al-Asrar, Khomeini attacked these liberal critics and writers as a "brainless" treacherous "lot" whose teeth the believers must 'smash ... with their iron fist’ and heads they should 'trample upon ... with courageous strides’.[211] Furthermore

Government can only be legitimate when it accepts the rule of God and the rule of God means the implementation of the Sharia. All laws that are contrary to the Sharia must be dropped because only the law of God will stay valid and immutable in the face of changing times. [211]

Cold War literature

During the cold war, a massive translation of Muslim Brotherhood thinkers started in Iran. The books of Sayyid Qutb and Abul A'la Al-Maududi were promoted through Muslim World League by Saudi patronage to confront communist propaganda in the Muslim world,[212] and helped to shape the ideology of Shi'i Islamists.[184] [213] The writings of Maududi and other Pakistani and Indian Islamists were translated into Persian and alongside the literature of Muslim Brotherhood, shaped the ideology of Shi'i Islamists.[184] [213]

The Shah's regime in Iran tolerated the Muslim Brotherhood literature for its anti-Communist value and also because it weakened the democratic Usulis camp.[citation needed] The Shah understood that this was the main ideological response of West to penetrating Soviet communism in Muslim world.[214] Soviet reports of the time indicate that Persian translations of this literature were smuggled to Afghanistan too, where western block intended to use Islamists against the communists.[215] Khaled Abou el-Fadl thinks that Sayyid Qutb was inspired by the German fascist Carl Schmidt.[216] He embodied a mixture of Wahhabism and Fascism and alongside Maududi, theorized the ideology of Islamism.

Maududi appreciated the power of modern state and its coercive potential that could be used for moral policing. He saw Islam as a nation-state that sought to mould its citizens and control every private and public expression of their lives, like fascists and communist states.[217] Iranian Shi'i Islamists had close links with Maududi's Jamaat-e-Islami, and after the 1963 riots in Qom, the Jamaat's periodical Tarjuman ul-Quran published a piece criticizing the Shah and supporting the Islamist currents in Iran.[218] Sayyid Qutb's works were translated by Iranian Islamists into Persian and enjoyed remarkable popularity both before and after the revolution. Prominent figures such as current Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei and his brother Muhammad Khamenei, Aḥmad Aram, Hadi Khosroshahi, etc. translated Qutb's works into Persian.[219][220] Hadi Khosroshahi was the first person to identify himself as Akhwani Shia.[221] Muhammad Khamenei is currently head of Sadra Islamic Philosophy Research Institute, and holds positions at Al-Zahra University and Allameh Tabataba'i University.[222] According to the National Library and Archives of Iran, 19 works of Sayyid Qutb and 17 works of his brother Muhammad Qutb were translated to Persian and widely circulated in the 1960s.[223] Reflecting on this import of ideas, Ali Khamenei said:

The newly emerged Islamic movement . . . had a pressing need for codified ideological foundations . . . Most writings on Islam at the time lacked any direct discussions of the ongoing struggles of the Muslim people . . . Few individuals who fought in the fiercest skirmishes of that battlefield made up their minds to compensate for this deficiency . . . This text was translated with this goal in mind. [224]

In 1952, Qutb had coined the term “American Islam”, a term later adapted by Ayatullah Khomeini after the Islamist revolution in Iran.[225]

The Islam that America and its allies desire in the Middle East does not resist colonialism and tyranny, but rather resists Communism only. They do not want Islam to govern and can not abide it to rule because when Islam governs, it will raise a different breed of humans and will teach people that it is their duty to develop their power and expel the colonialists . . . American Islam is consulted on the issued of birth control, the entry of women into Parliament, and on matters that impair ritual ablutions. However, it is jot consulted on the matter of our social and economic affairs and fiscal system, nor is it consulted on political and national affairs and our connections with colonialism.[226]

In 1984 the Iranian authorities honoured Sayyid Qutb by issuing a postage stamp showing him behind the bars during trial.[227]

Khomeini's early opposition to the shah

- White Revolution

In January 1963, the Shah of Iran announced the "White Revolution", a six-point programme of reform calling for land reform, nationalization of the forests, the sale of state-owned enterprises to private interests, electoral changes to enfranchise women and allow non-Muslims to hold office, profit-sharing in industry, and a literacy campaign in the nation's schools. Some of these initiatives were regarded as Westernizing trends by traditionalists and as a challenge to the Shi'a ulama (religious scholars). Khomeini denounced them as "an attack on Islam",[228] and persuaded other senior marjas of Qom to decree a boycott of the referendum on the White Revolution. When Khomeini issued a declaration denouncing both the Shah and his reform plan, the Shah took an armored column to Qom, and delivered a speech harshly attacking the ulama as a class.

After his arrest in Iran following the 1963 riots, leading Ayatullahs had issued a statement declaring Ayatullah Khomeini a legitimate Marja. This is widely thought to have prevented his execution.[229]

- 15 Khordad Uprising

In June of that year Khomeini delivered a speech at the Feyziyeh madrasah drawing parallels between the Sunni Muslim caliph Yazid—who is perceived as a 'tyrant' by Shias and responsible for the death of Imam Ali—and the Shah, denouncing the Shah as a "wretched, miserable man," and warning him that if he did not change his ways the day would come when the people would no longer tolerate him. Two days later, Khomeini was arrested and transferred to Tehran.[230][231] Following this action, there were three days of major riots throughout Iran, know as the Movement of 15 Khordad.[232][233] Although they were crushed within days by the police and military, the Shah's regime was taken by surprise by the size of the demonstrations, and they established the importance and power of (Shia) religious opposition to the Shah, and the importance of Khomeini as a political and religious leader.[234]

- Opposition to capitulation

Khomeini attacked the Shah not only for the White Revolution but for violating the constitution, the spread of moral corruption, submission to the United States and Israel, and in October 1964 for "capitulations" or diplomatic immunity granted by the Shah to American military personnel in Iran.[235][236] The "capitulations" aka "status-of-forces agreement", stipulating that U.S. servicemen facing criminal charges stemming from a deployment in Iran, were to be tried before a U.S. court martial, not an Iranian court.

In November 1964, after his latest denunciation, Khomeini was arrested and held for half a year. Upon his release, Khomeini was brought before Prime Minister Hassan Ali Mansur, who tried to convince him to apologize for his harsh rhetoric and going forward, cease his opposition to the Shah and his government. When Khomeini refused, Mansur slapped him in the face in a fit of rage. Two months later, Mansur was assassinated on his way to parliament. Four members of the Fadayan-e Islam, a Shia militia sympathetic to Khomeini, were later executed for the murder.[237]

- Exile

Khomeini spent more than 14 years in exile, mostly in the holy Iraqi city of Najaf (from October 1965 to 1978, when he was expelled by then-Vice President Saddam Hussein).[238] In Najaf, Khomeini took advantage of the Iraq-Iran conflict and launched a campaign against the Pahlavi regime in Iran. Saddam Hussein gave him access to the Persian broadcast of Radio Baghdad to address Iranians and made it easier for him to receive visitors.[239]

By the time Khomeini was expelled from Najaf, discontent with the Shah had intensified. Khomeini visited Neauphle-le-Château, a suburb of Paris, France, on a tourist visa on 6 October 1978.[240][241]

Non-Khomeini sources of Islamism

Gharbzadegi

In 1962, Jalal Al-e-Ahmad published a book or pamphlet called of the book Occidentosis (Gharbzadegi): A Plague from the West. Al-e-Ahmad, who was from a deeply religious family but had had a Western education and been a member of the Tudeh (Communist) party,[242] argued that Iran was intoxicated or infatuated (zadegi) with Western (gharb) technology, culture, products, and so had become a victim of the West's "toxins" or disease. The adoption and imitation of Western models and Western criteria in education, the arts, and culture led to the loss of Iranian cultural identity, and a transformation of Iran into a passive market for Western goods and a pawn in Western geopolitics.[243][244] Al-e-Ahmad "spearheaded" the search by Western educated/secular Iranians for "Islamic roots", and although he advocated a return to Islam his works "contained a strong Marxist flavor and analyzed society through a class perspective."[245]

Al-e-Ahmad "was the only contemporary writer ever to obtain favorable comments from Khomeini", who wrote in a 1971 message to Iranian pilgrims on going on Hajj,

"The poisonous culture of imperialism [is] penetrating to the depths of towns and villages throughout the Muslim world, displacing the culture of the Qur'an, recruiting our youth en masse to the service of foreigners and imperialists..."[246]

At least one historian (Ervand Abrahamian) speculates Al-e-Ahmad may have been an influence on Khomeini's turning away from traditional Shi'i thought towards populism, class struggle and revolution.[245] Fighting Gharbzadegi became part of the ideology of the 1979 Iranian Revolution—the emphasis on nationalization of industry, "self-sufficiency" in economics, independence in all areas of life from both the Western (and Soviet) world. He was also one of the main influences of the later Islamic Republic president Ahmadinejad.[247] The Islamic Republic issued a postage stamp honoring Al-e-Ahmad in 1981.[248]

Socialist Shi'ism

One element of Iran's revolution not found in Sunni Islamist movements was what came to be called "Socialist Shi'ism",[249] (also "red Shiism" as opposed to the "black Shiism" of the clerics).[250]

Iran's education system was "substantially superior" to that of its neighbors, and by 1979 had about 175,000 students, 67, 000 studying abroad away from the supervision of its oppressive security force the SAVAK. The early 1970s saw a "blossoming of Marxist groups" around the world including among Iranian post-secondary students.[249]

After one failed uprising, some of the young revolutionaries, realizing that the religious Iranian masses were not relating to Marxist concepts, began projecting "the Messianic expectations of communist and Third World peoples onto Revolutionary Shi'ism.", i.e. socialist Shi'ism.[249] Ali Shariati was "the most outspoken representative of this group", and a figure without equivalent in "fame or influence" in Sunni Islam.[249] He had come from a "strictly religious family" but had studied in Paris and been influenced by the writings of Jean-Paul Sartre, Frantz Fanon and Che Guevara.[251]

Socialist Shia believed Imam Hussein was not just a holy figure but the original oppressed one (muzloun), and his killer, the Sunni Umayyad Caliphate, the "analog" of the modern Iranian people's "oppression by the shah".[249] His killing at Karbala was not just an "eternal manifestation of the truth but a revolutionary act by a revolutionary hero".[252]

Shariati was also a harsh critic of traditional Usuli clergy (including Ayatullah Hadi al-Milani), who he and other leftist Shia believed were standing in the way of the revolutionary potential of the masses,[253] by focusing on mourning and lamentation for the martyrs, awaiting the return of the messiah, when they should have been fighting "against the state injustice begun by Ali and Hussein".[254]

Shariati not only influenced young Iranians and young clerics,[255] he influenced Khomeini. Shariati popularized a saying from the 19th century, 'Every place should be turned into Karbala, every month into Moharram, and every day into Ashara'.[252] Later Khomeini used it as a slogan.[256]

The "phenomenal popularity" of Shari'ati among the "young intelligentsia"[257][250] helped open up the "modern middle class" to Khomeini. Shari'ati was often anticlerical but Khomeini was able to "win over his followers by being forthright in his denunciations of the monarchy; by refusing to join fellow theologians in criticizing the Husseinieh-i Ershad; by openly attacking the apolitical and the pro-regime `ulama; by stressing such themes as revolution, anti-imperialism, and the radical message of Muharram; and by incorporating into his public declarations such `Fanonist` terms as the `mostazafin will inherit the earth`, `the country needs a cultural revolution,` and the `people will dump the exploiters onto the garbage heap of history.` [257]

Shariati was also influenced by anti-democratic Islamist ideas of Muslim Brotherhood thinkers in Egypt and he tried to meet Muhammad Qutb while visiting Saudi Arabia in 1969.[258] A chain smoker, Shariati died of a heart attack while in self-imposed exile in Southampton, UK on June 18, 1977.[259]

Ayatullah Hadi Milani, the influential Usuli Marja in Mashhad during the 1970s, had issued a fatwa prohibiting his followers from reading Ali Shariati's books and islamist literature produced by young clerics. This fatwa was followed by similar fatwas from Ayatullah Mar'ashi Najafi, Ayatullah Muhammad Rouhani, Ayatullah Hasan Qomi and others. Ayatullah Khomeini refused to comment.[260]

Baqir al-Sadr

In Iraq, another cleric from a distinguished clerical family, Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (1935-1980), became the ideological founder of the Islamist Islamic Dawa Party (which had similar goals to that of Muslim Brotherhood), and author of several influential works including Iqtisaduna on Islamic economics, and Falsafatuna (Our Philosophy).[261] Like the 1970-1980 version of Khomeini, he sought to combine populism with religious revival, claiming that "the call for return to Islam is a call for a return to God’s dispensation, and necessitates a 'social revolution' against 'injustice' and 'exploitation.'"[262]

After a military coup in 1958, a pro-soviet General Abd al-Karim Qasim came to power in Iraq, putting centers of religious learning, such as Najaf were al-Sadr worked under pressure from the Qasim regime's attempts to curb religion as an obstacle to modernity and progress. Ayatollah Muhsin al-Hakim, located in Iraq and one of the leading Shi'i clerics at the time, issued fatwa against communism.[263] Ayatullah Mohsin al-Hakim disapproved of al-Sadr's activities and ideas.[264] Qasim was overthrown in 1963, by the pan-Arabist Ba'ath party, but the crackdown on Shi'i religious centers continued, closing periodicals and seminaries, expelling non-Iraqi students from Najaf. Ayatullah Mohsin al-Hakim called Shias to protest. This helped Baqir al-Sadr's rise to prominence as he visited Lebanon and sent telegrams to different international figures, including Abul A'la Maududi.[265]

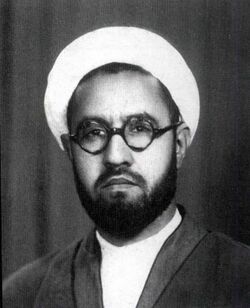

Mahmoud Taleghani

Mahmoud Taleghani (1911–1979) was another politically active Iranian Shi'i cleric and contemporary of Khomeini and a leader in his own right of the movement against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. A founding member of the Freedom Movement of Iran, he has been described as a representative of the tendency of many "Shia clerics to blend Shia with Marxist ideals in order to compete with leftist movements for youthful supporters" during the 1960s and 1970s.[266] a veteran in the struggle against the Pahlavi regime, he was imprisoned on several occasions over the decades, "as a young preacher, as a mid-ranking cleric, and as a senior religious leader just before the revolution,"[267] and served a total of a dozen years in prison.[268] In his time in prison he developed connections with leftist political prisoners and the influence of the left on his thinking was reflected in his famous book Islam and Ownership (Islam va Malekiyat) which argued in support of collective ownership "as if it were an article of faith in Islam."[267]