Engineering:Livens Projector

| Livens Projector | |

|---|---|

British soldiers loading and fitting electrical leads to a battery of Livens projectors | |

| Type | Mortar |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1916–1918 |

| Used by | British Empire United States |

| Wars | World War I |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Captain William Howard Livens, Royal Engineers |

| Designed | 1916 |

| No. built | 140,000 projectors 400,000 bombs[1][2][3] |

| Specifications | |

| Shell | Gas drum |

| Calibre | 8 inches (200 mm) |

| Elevation | fixed |

| Traverse | fixed |

| Maximum firing range | 1,640 yd (1,500 m) |

| Filling | phosgene,[4] flammable oil |

| Filling weight | 30 lb (14 kg)[5] |

Detonation mechanism | Impact |

The Livens Projector was a simple mortar-like weapon that could throw large drums filled with flammable or toxic chemicals.[6]

In the First World War, the Livens Projector became the standard means of delivering gas attacks by the British Army and it remained in its arsenal until the early years of the Second World War.[7]

History

The Livens Projector was created by Captain William Livens of the Royal Engineers.[8] Livens designed a number of novel weapons, including a large-calibre flame thrower, to engulf German trenches in burning oil, that was deployed at the Somme in 1916. (One of these weapons was partially excavated in 2010 for an episode of archaeological television programme Time Team, having been buried when the tunnel in which it was being built was hit by a German shell.) In the Second World War, he worked on petroleum warfare weapons such as the flame fougasse and various other flame weapons.[9][10]

Prior to the invention of the Livens Projector, chemical weapons had been delivered either by cloud attacks or chemical-filled shells fired from howitzers. Cloud attacks at first were made by burying gas-filled cylinders just beyond the parapet of the attacker's trenches and then opening valves on the tanks when the wind was right. (Later British practice was to bring up flatcars with gas cylinders on a line parallel to the front to be attacked, and open the cylinders without removing them from the rail car.[11]) This allowed a useful amount of gas to be released but there was danger that the wind would change and the gas drift back over the attacking troops. Chemical shells were much easier to aim but could not deliver nearly as much gas as a cylinder.

Livens was in command of Z Company, the unit charged with developing and using flame and chemical weapons. Flame throwers and various means of dispensing chemicals had proven frustratingly limited in effect. During an attack on the Somme, Z Company encountered a party of Germans who were well dug in. Grenades did not shift them and Livens improvised a giant Molotov cocktail using two 5-imperial-gallon (23 L) oil cans. When these were thrown into the German positions they were so effective that Harry Strange wondered whether it would be better to use containers to carry the flame to the enemy rather than relying on a complex flame thrower.[12][13]

Reflecting on the incident, Livens and Strange considered how a really large shell filled with fuel might be thrown by a mortar.[14] Livens went on to develop a large, simple mortar that could throw a three-gallon drum of oil which would burst when it landed, spreading burning oil over the target.[15] Livens came to the attention of General Hubert Gough who was impressed by his ideas and "wangled" everything that Livens needed for his large projector.[16]

On 25 July 1916 at Ovillers-la-Boisselle during the Battle of the Somme, Z Company used eighty projectors when the Australians were due to attack Pozières. Since the early versions had a short range, it was necessary to, first, neutralize German machine gun nests, and, then place the projectors 200 yd (180 m) forward into no-man's-land.[15]

Z Company rapidly developed the Livens Projector, increasing its range to 350 yd (320 m) and eventually an electrically triggered version with a range of 1,300 yd (1,200 m) used at the Battle of Messines in June 1917.[15]

The Livens Projector was then modified to fire canisters of poison gas rather than oil. This system was tested in secret, at Thiepval in September 1916 and Beaumont-Hamel in November.[15] The Livens Projector was able to deliver a high concentration of gas a considerable distance. Each canister delivered as much gas as several gas shells. Without the need to reload, a barrage could be launched quickly, catching the enemy by surprise. Although the projectors were single-shot weapons they were cheap and used in hundreds or even thousands.

The Livens Projector was also used to fire other substances. At one time or another the drums contained high explosive, oil and cotton-waste pellets, thermite, white phosphorus and "stinks". Used as giant stink bombs to trick the enemy, "stinks" were malodorous but harmless substances such as bone oil and amyl acetate used to simulate a poison gas attack, compelling the opponents to don cumbersome masks (which reduced the efficiency of German troops) on occasions when gas could not be safely employed.[17] Alternatively, "stinks" could be used to artificially prolong the scale, discomfort and duration of genuine gas-attacks i.e. alternating projectiles containing "stinks" with phosgene, adamsite or chloropicrin. There was even a design for ammunition containing a dozen Mills bombs in the manner of a cluster bomb.[18] The Livens Projector remained in the arsenal of the British Army until the early years of the Second World War.[7] In the context of the Invasion Scare in the early years of World War II, over 25,000 Livens Projectors were produced for the defense of Great Britain between 1939-1942.[19]

Description

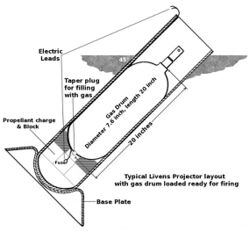

The Livens Projector was designed to combine the advantages of gas cylinders and shells by firing a cylinder tank at the enemy.[20] It consisted of a simple metal pipe that was set in a ground at a 45-degree angle. Specifications varied during the war. The early field improvisations in July 1916 near La Boselle based the barrel on 12-inch-diameter (300 mm) oil drums, the projectile was an oil can. The production model was decided on in December 1916 after further successful field trials on the Somme. It was based on spare 8-inch-diameter (200 mm) oxy-acetylene welded tubing.[21]

The 8-inch barrel became standard and was first used in number when 2,000 fired a salvo in the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. Barrels were supplied in three lengths depending on required range: 2 ft 9 in (84 cm) for short range, 3 ft (91 cm) for medium range and 4 ft 3 in (130 cm) for maximum range.[22] A drum 7.6 in (193 mm) in diameter and 20 in (508 mm) long, containing 30 lb (14 kg) of gas, was shot out by an electrically initiated charge, giving it a range of about 1,500 m (1,640 yd).[5] On impact with the target, a burster charge would disperse the chemical filling over the area.[23]

It was also used to project flammable oil, as with 1,500 drums fired before the Battle of Messines in June 1917.[24] Oil was also tried on 20 September 1917 during the Battle of the Menin Road Ridge with 290 projectors used in support of an attempt to capture Eagle Trench east of Langemarck. This included concrete bunkers and machine gun nests but the drums did not land in the trenches and failed to suppress the German defenders there.[25][26]

Use

As a rule, the projectors were sited out in the open some little way behind the front line so that digging, aiming (either by direct line of sight or by compass) and wiring up the electrical leads were easier. When camouflaged the positions would be unknown to the enemy so that although the enemy was able to recognise the direction of the location by the discharge flash he would be uncertain of the range. As such these installations could only be carried out at night. The digging of the narrow trenches did not involve much labour and later in the war the projectors were only buried to a depth of about a one foot (30 cm), instead of up to their muzzles.[27] The projector was somewhat unreliable. To safeguard friendly forces from 'shorts' an area immediately ahead of the projector battery was cleared of troops before firing. This area allowed for the possibility of drums reaching only 60% of the estimated range and veering 20 degrees from the central line of fire by the wind or from some other cause.[27]

The projectors were also inaccurate,

It was distinctly laid down as a principle that, owing to the inaccuracy of the weapon, the most suitable targets were areas which were either strongly held or which contained underground shelters in which the occupants were safe against artillery fire.[28]

A British training manual of 1940 described it as,

...a simple weapon which does not aspire to great accuracy. Its range is limited to about 1,800 yards (1,600 m); the noise of firing is very loud, and at night is accompanied by a vivid flash..... Projectors are the principal armament of C.W. companies, RE.[7]

The projector's unreliability and inaccuracy were more than made up for by the weapon's principal advantages: it was a cheap, simple and extremely effective method of delivering chemical weapons. Typically, hundreds, or even thousands, of Livens projectors would be fired in unison during an attack to saturate the enemy lines with poison gas.

| “ | This weapon was one which, if the installation had been carried out carefully and camouflaged, was capable not only of flooding the enemy's trenches unexpectedly with a deadly gas a few seconds after notice of its approach had been given by the flash of the discharge but of establishing such a high concentration of poisonous vapour—especially in the neighbourhood where each drum fell—that no respirator could be expected to give adequate protection to its wearer. [...] This 'mass effect' had, of course, not been achieved to any marked extent during the Somme battle, when only a dozen or two makeshift drums were discharged at a time; but now that we were proposing to fire several thousand of them simultaneously in a single operation, the effect might well be expected to be—and in fact was—profound. In a captured German document, dated 27/12/17, an English gas projector bombardment was described as follows: 'The discharge in sight and sound resembles a violent explosion; volcanic sheets of flame or the simultaneous occurrence of many gun flashes, thick noise of impact up to 25 seconds after the flash of discharge. The mines, contrary to the manner of discharge, do not all burst exactly simultaneously: the noise resembles that of an exploding dump of hand-grenades. Fragmentation is very slight'.[29] | ” |

German equivalent

The Livens projector provided the Germans with inspiration for a similar device, known as the Gaswurfminen.[30] Over eight hundred of these were used against the Italian Army at the Battle of Caporetto.

Surviving examples

- Several barrels with bases are displayed at Sanctuary Wood Museum Hill 62 Zillebeke, Belgium[31]

- Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 in Zonnebeke

- Several barrels in the ground at the Yorkshire Trench & Dug-out in Ypres

- In Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres

- A barrel and two projectiles are displayed at the Museum of Lincolnshire Life, Lincoln, United Kingdom

See also

- Poison gas in World War I

- Heavy mortars

Notes

- ↑ Jones (2007) p. 43

- ↑ National Archive, T 173/330 – Royal Commission on awards to inventors – Livens

- ↑ Ministry of Munitions History 1922, p. 100

- ↑ "The military policy laid down in May, 1917... It [C.G. i.e. phosgene] was the only lethal substance allocated to projector drums". Ministry of Munitions 1922, Volume XI, Part II Chemical Warfare Supplies. p. 8

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Jones (2007) p. 42

- ↑ "1916 – Other Corps activities". Corps History – Part 14. Royal Engineers Museum. http://www.remuseum.org.uk/corpshistory/rem_corps_part14.htm#1916%20-%20Other%20Corps%20activities.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 The Use of Gas in the Field, 1940

- ↑ Palazzo, 2002, p. 103.

- ↑ LeFebure, 1926, p. 60

- ↑ Banks, 1946, p. 33

- ↑ Ian V. Hogg, Gas, New York: Ballantine, 1975

- ↑ Croddy, 2001, p138.

- ↑ Awards to Inventors, 1922, p20

- ↑ Awards to Inventors, 1922, p30

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 "Major William Howard Livens (1889–1964)". Notable Individuals of the Great War: # 2. I – L.. The Western Front Association. http://www.westernfrontassociation.com/great-war-on-land/general-interest/815-notable-individuals.html.

- ↑ Awards to Inventors, 1922, pp 51–62

- ↑ Foulkes 1934, p. 169.

- ↑ Rawson 2006, p. 272.

- ↑ U.K. Central Statistical Office, Fighting with Figures, 1995, Table 7.13.

- ↑ LeFebure (1926) p. 48–63

- ↑ Ministry of Munitions History 1922, page 98–99

- ↑ Ministry of Munitions History 1922, page 99–100

- ↑ United States Dept. of War, 1942, pp 12–13

- ↑ Jones 2007, page 44

- ↑ Farndale 1986, page 207

- ↑ British Official History (Military Operations France & Belgium 1917), page 270

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Foulkes 1934, p. 202.

- ↑ Foulkes 1934, p. 203.

- ↑ Foulkes 1934, pp. 199–200.

- ↑ Nash, David (1980). Imperial German Army Handbook, 1914–1918. I. Allen. pp. 107. ISBN 978-0711009684.

- ↑ 03. Lance-mines alliés (allied mine-throwers) – Page 3 – Canons de la Grande Guerre / WW1 guns" Bernard Plumier: webpage (in French)

References

- Banks, Sir Donald (1946). Flame Over Britain, a Personal Narrative of Petroleum Warfare. Sampson Low, Marston and Co. OCLC 2037548.

- Croddy, Eric (2001). Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Comprehensive Survey for the Concerned Citizen. Springer-Verlag New York. ISBN 978-0-387-95076-1. https://archive.org/details/chemicalbiologic00crod.

- Farndale, M. (1986). Western Front 1914–18. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery (1st ed.). London: Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 978-1-870114-00-4.

- Foulkes, Charles Howard (2001). "Gas!" The Story of the Special Brigade (The Naval & Military Press, Ukfield ed.). Blackwood & Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-088-0.

- History of the Ministry of Munitions Part I: Trench Warfare Supplies. XI (Facs. repr. Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). 2008. ISBN 978-1-84734-885-2.

- Jones, Simon (2007). World War I Gas Warfare Tactics and Equipment. Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-151-9.

- LeFebure, Victor (1923). The Riddle of the Rhine: Chemical Strategy in Peace and War: An Account of the Critical Struggle for Power and for the Decisive War Initiative, the Campaign Fostered by the Great Rhine Factories and the Pressing Problems Which they Represent, a Matter of Pre-eminent Public Interest Concerning the Sincerity of Disarmament, the Future of Warfare, and the Stability of Peace. New York: The Chemical Foundation. OCLC 1475439. https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1272. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- Minutes of Proceedings before the Royal Commission on Awards to Inventors. National Archives T 173/702. Treasury. 29 May 1922.

- Palazzo, A. (2003). Seeking Victory on the Western Front: The British Army and Chemical Warfare in World War I (Bison Books ed.). London: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-8774-7. https://archive.org/details/seekingvictoryon00albe.

- United States Department of War (1942). Livens Projector M1 TM 3-325

- Rawson, Andrew (2006). British Army Handbook 1914–1918. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-3745-0.

- The Use of Gas in the Field. Military Training Pamphlet No. 5. War Office. 1943. OCLC 56345099.

Further reading

- Richter, Donald (1992). Chemical Soldiers – British Gas Warfare in World War I. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1113-3.

- United States. War Department. (1942). Livens projector MI. United States. Government Printing Office.. https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc29948/.

External links

- Worldscapes : Chemical & Biological Warfare

- Royal Engineers Museum, First World War – Livens Projector

- News Briefs (Livens projector shown). British Pathe. 16 March 1942. 1:00 minutes in.

- "Firing Livens Projectors". flickr. 7 June 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/45841855@N02/7350013624/in/photostream/.

- "Loading Drums into Livens Projectors". flickr. 7 June 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/45841855@N02/7164798599/in/photostream/.

- "Loading Charges into Livens Projectors". flickr. 7 June 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/45841855@N02/7164788265/in/photostream/.

- "Captured British Livens Projectors". flickr. 22 May 2012. https://www.flickr.com/photos/45841855@N02/7251475488/in/photostream/.

|