Engineering:Lateen

A lateen (from French latine, meaning "Latin"[1]) or latin-rig is a triangular sail set on a long yard mounted at an angle on the mast, and running in a fore-and-aft direction. The settee can be considered to be an associated type of the same overall category of sail.[2]

The lateen originated in the Mediterranean as early as the 2nd century AD, during Roman times, and became common there by the 5th century. The wider introduction of lateen rig at this time coincided with a reduction in the use of the Mediterranean square rig of the classical era. Since the performance of these two rigs is broadly similar, it is suggested that the change from one to the other was on cost grounds, since lateen used fewer components and had less cordage to be replaced when it wore out.[2]

Arab seafarers adopted the lateen rig at a later date – there is some limited archaeological evidence of lateen rig in the Indian Ocean in the 13th century AD and iconographic evidence from the 16th century.[2] It has been suggested that this Arab use of lateen transferred to Austronesian maritime technology in the Far East, giving rise to the various fore and aft rigs used in that region, such as the crab claw sail.[3]

The lateen sail played a prominent part in the shifts in maritime technology that occurred as Mediterranean and Northern ship construction traditions merged in the 16th century, with the lateen mizzen being, for a time, universally used in the full-rigged ships of the time – though later supplanted by gaff rig in this role.[2]

History

Mediterranean origin

The lateen was developed in the eastern Mediterranean as early as the 2nd century AD, during Roman times. It became common by the 5th century.[2]

The lateen also exists as a subtype: the settee. Instead of being a triangular sail, this has a short vertical luff – having the appearance of a triangular lateen with the front corner cut off. Both types of lateen were likely used from an early date on: a 2nd-century AD gravestone depicts a quadrilateral lateen sail (also known as a settee), while a 4th-century mosaic shows a triangular one, which was to become the standard rig throughout the Middle Ages.[5] The earliest archaeologically excavated ship that has been reconstructed with a lateen rig is dated to ca. 400 AD (Yassi Ada II), with a further four being attested prior to the Arab advance to the Mediterranean.[6] The Kelenderis ship mosaic (late 5th to early 6th century)[7][8] and the Kellia ship graffito from the early 7th century complement the picture.[8]

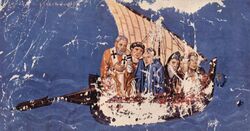

By the 6th century, the lateen sail had largely replaced the square sail throughout the Mediterranean, the latter almost disappearing from Mediterranean iconography until the mid-13th century.[9] It became the standard rig of the Byzantine dromon war galley and was probably also employed by Belisarius' flagship in the 532 AD invasion of the Vandal Kingdom.[10][11] The fully triangular lateen and the settee continued to coexist in the middle Byzantine period, as evidenced by Christian iconography,[4] as well as a recent find of a graffito in the Yenikapı excavations.[12] In the 12th to 13th centuries the rigging underwent a change when the hook-shaped masthead made way for an arrangement more akin to a barrel-like crow's nest.[13]

After the Muslim conquests, the Arabs adopted the lateen sail by way of the Coptic populace, which shared the existing Mediterranean maritime tradition and continued to provide the bulk of galley crews for Muslim-led fleets for centuries to come.[14] This is also indicated by the terminology of the lateen among Mediterranean Arabs which is derived from Greco-Roman nomenclature.[15] More detailed research into their early use of the lateen is hampered by a distinct lack of unequivocal depictions of sailing rigs in early Islamic art.[16][16] A glazed pottery dish from Saracenic Dénia dating to the 11th century is at present the earliest securely identifiable example found in the Mediterranean.[16]

Nile River

From the Mediterranean, the lateen sail spread to the Nile River in Egypt, where the lateen-rigged felucca was developed.[17]

Diffusion to Indian Ocean

The emergence of new evidence for the development and spread of the lateen sail in the ancient Mediterranean in recent decades has led to a reevaluation of the role of Arab seafaring in the Indian Ocean in that process.

The origin of the lateen sail has often been attributed by scholars to the Indian Ocean and its introduction into the Mediterranean traditionally ascribed to the Arab expansion of the early-7th century. This was due mainly to the earliest (at that time) iconographic depictions of lateen rigged ships from the Mediterranean post-dating the Islamic expansion into the Mediterranean basin...It was assumed that the Arab people who invaded the Mediterranean basin in the 7th century carried with them the sailing rig familiar to them. Such theories have been superseded by unequivocal depictions of lateen-rigged Mediterranean sailing vessels which pre-date the Arab invasion.[18][19]

There has been according to some a reversal of the earlier scholarly opinion on the direction of diffusion of the lateen rig in the Indian Ocean and its gulfs. According to them searches for lateen sails in India were inconclusive.[20] Since lateen sails were absent from Indian inland waters, that is in regions remote from foreign influences, as late as the mid-20th century, the hypothesis of an Indian origin appears a priori implausible.[21] The earliest evidence for the lateen in Islamic art adjacent to the Indian Ocean occurs in a 13th-century Egyptian artifact which, though, is assumed to show a Mediterranean vessel.[22] Excavated depictions of Muslim vessels along the Eastern African coast uniformly show square sails before 1500.[23]

After 1500, the situation in the Indian Ocean dramatically changed, with nearly all vessels now being lateen rigged.[22] As Mediterranean hull design and construction methods are known to have been subsequently adopted by Eastern Muslim shipbuilders, it is assumed that this process also included the lateen rigging of the novel caravel.

Later development

Until the 14th century, the lateen sail was employed primarily on the Mediterranean Sea, while the Atlantic and Baltic (and Indian Ocean) vessels relied on square sails. The Northern European adoption of the lateen in the Late Middle Ages was a specialized sail that was one of the technological developments in shipbuilding that made ships more maneuverable, thus, in the historian's traditional progression, permitting merchants to sail out of the Mediterranean and into the Atlantic Ocean; caravels typically mounted three or more lateens. However, the great size of the lateen yardarm makes it difficult and dangerous to handle on larger ships in stormy weather, and with the development of the carrack, the lateen was restricted to the mizzen mast. In the early nineteenth century, the lateen was replaced in European ships by the driver or spanker.

The lateen survived as a rigging choice for mainsails of small craft where local conditions were favorable. For instance, barge-like vessels in the American maritimes north of Boston, called gundalows, carried lateen rigs throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Likewise, lateen sail survived in the Baltic until the late 19th century. Because the yard pivots on its point of attachment to the mast, the entire sail and yard can be swiftly dropped. This was an advantage when navigating the tidal riverways of the region, which often required passage under bridges. The balancelle, a Mediterranean coasting and fishing boat of the 19th century, also used a single lateen sail.

One of the disadvantages of the lateen in the modern form described below is the fact that it has a "bad tack". The sail is to the side of the mast, on one tack that puts the mast directly against the sail on the leeward side, where it can significantly interfere with the airflow over the sail. On the other tack the sail is pushed away from the mast, greatly reducing the interference. On modern lateens, with their typically shallower angles, this tends to disrupt the airflow over a larger area of the sail.[citation needed]

However, there are forms of the lateen rig, as in vela latina canaria, where the spar is changed from one side to the other when tacking. This way the rig doesn't suffer these airflow disruptions that come from the sail pushed against the mast.[24]

The lateen sail can also be tacked by loosening the yard upper brace, tightening the lower brace until the yard is in vertical position, and twisting the yard on the other side of the mast by a tack. Another way of tacking with a lateen sail is to loosen the braces, lift the yard vertical, detach the sheet and tack, and turn the sail on the other side of the mast in front of the mast, and reattach the sheet and tack. This method is described in Björn Landström's The Ship.[citation needed]

The lateen rig was also the ancestor of the Bermuda rig, by way of the Dutch bezaan rig. In the 16th century, when Spain ruled the Netherlands, the lateen rigs were introduced to Dutch boat builders, who soon modified the design by omitting the mast and fastening the lower end of the yard directly to the deck, the yard becoming a raked mast with a full-length, triangular (leg-of-mutton) mainsail aft. Introduced to Bermuda early in the 17th century, this developed into the Bermuda rig, which, in the 20th century, was adopted almost universally for small sailing vessels.[citation needed]

Lateen replacement of square rig

It is a widespread misconception that the lateen rig replaced square rig because of better windward performance and greater manoeuvrability. A study of the relative effectiveness of the two shows that their performance was actually very similar. These results apply both when working to windward and when sailing downwind. (Furthermore, differences in performance are derived as much from the hull shape as the type of rig.) It is concluded that there was no evolutionary technological development that gave improved sailing performance in the 5th century AD change from the Mediterranean square rig to lateen, and that factors other than windward performance must have dictated this change.[25]

The Mediterranean Square Rig underwent a simplification in the 5th century AD, with reduction in the number of components. Most obviously, in the archaeological context, this included the absence of brails (and the distinctive lead rings through which these ropes were led). This change is suggested to be on cost grounds, both reducing the expense of a new build and of ongoing maintenance. This would have given some degradation of performance of this type of square rig. Lateen was already available as an alternative and, having fewer component parts, could compete on cost but maintained the performance of the original Mediterranean Square Rig. This coincided with innovation in hull construction methods as the edge-to-edge joining of the hull planking with pegged tenons (a "shell first" construction technique) started to be replaced with the early evolutionary phases of "frame first" carvel construction. This is also suggested to be driven by costs. Therefore the change from square rig to lateen in the 5th century is considered to be driven by construction and maintenance costs, not by any significant difference in sailing performance.[26]

Modern small-boat lateen sails

The modern "lateen" is more accurately a crab claw sail than a traditional loose-footed Mediterranean lateen. They are characterized by the addition of a spar along the foot of the sail. The lower spar is horizontal and is attached to the mast where it crosses. The front ends of both spars are joined. Both joints are designed to allow free rotation in all directions. The sheet is attached to the lower spar and the halyard to the upper spar. The geometry of the sail is such that the upper and lower spars are confined to a plane parallel to the mast. This results in the sail conforming a conic section, identical to half of the Rogallo wing commonly found in kites and hang gliders.

The modern lateen is often used as a simple rig for catboats and other small recreational sailing craft. In its most basic form, it requires only two lines, a halyard and a sheet, making it very simple to operate. Often, additional lines are used to pull down the lower spar and provide tension along the upper and lower spars, providing greater control over the sail shape.

Since the upper and lower spars provide a frame for the sail, the camber of the sail is simply a function of how tightly the spars stretch the sail. This means that lateen sails are often cut flat, without the complex cutting and stitching required to provide camber in Bermuda rig sails. Curved edges, when mated with the straight spars, provide all or nearly all of the sail curvature needed.

Sunfish rig: single unstayed mast with single sail. The vessel tacks.

Single-outrigger proa: single mast with crab claw sail. The vessel is double-ended and is shunted, not tacked.

See also

- Crab claw sail

- Settee (a triangular sail with the front corner cut off)

- Tanja sail, a type of sail sometimes mistaken as lateen sail.

Citations

- ↑ "the definition of lateen". http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/lateen.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Whitewright 2012a.

- ↑ Anderson 2018.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Whitewright 2009, p. 100.

- ↑ Casson 1995, pp. 243–245

- ↑ Castro et al. 2008, p. 352

- ↑ Pomey 2006.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Whitewright 2009, p. 98f.

- ↑ Castro et al. 2008, p. 2

- ↑ Basch 2001, p. 63

- ↑ Casson 1995, p. 245, fn. 82

- ↑ Günsenin & Rieth 2012, p. 157

- ↑ Whitewright 2009, p. 101

- ↑ Campbell 1995, pp. 9–10

- ↑ White 1978, pp. 256f.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Whitewright 2012b, p. 589.

- ↑ Bisson, Wilfred J. (2020). "Introduction: Travel Technology". in Burns, William E.. Science and Technology in World History, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 226. ISBN 978-1-440-87116-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=h9zQDwAAQBAJ&q=nile+%22lateen+sail%22.

- ↑ Whitewright 2009, p. 98

- ↑ To the same effect: Casson 1954, pp. 214f.; Campbell 1995, pp. 7f.; White 1978

- ↑ White 1978, pp. 257f.

- ↑ White 1978, p. 257

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 White 1978, p. 258

- ↑ White 1978, p. 259

- ↑ "YouTube". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8TtcZjAuF4A.[|permanent dead YouTube link|dead YouTube link}}]

- ↑ Whitewright 2011.

- ↑ Whitewright, Julian (April 2012). "Technological Continuity and Change: The Lateen Sail of the Medieval Mediterranean". Al-Masāq 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09503110.2012.655580.

General and cited sources

- Anderson, Atholl (2018). "SEAFARING IN REMOTE OCEANIA Traditionalism and Beyond in Maritime Technology and Migration". in Cochrane, Ethan E; Hunt, Terry L.. The Oxford handbook of prehistoric Oceania. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-992507-0.

- Basch, Lucien (2001), "La voile latine, son origine, son évolution et ses parentés arabes", in Tzalas, H., Tropis VI, 6th International Symposium on Ship Construction in Antiquity, Lamia 1996 proceedings, Athens: Hellenic Institute for the Preservation of Nautical Tradition, pp. 55–85

- Campbell, I. C. (1995), "The Lateen Sail in World History", Journal of World History 6 (1): 1–23, http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/journals/jwh/jwh061p001.pdf, retrieved 2009-10-08

- Casson, Lionel (1954), "The Sails of the Ancient Mariner", Archaeology 7 (4): 214–219

- Casson, Lionel (1995), Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0-8018-5130-8

- Castro, F.; Fonseca, N.; Vacas, T.; Ciciliot, F. (2008), "A Quantitative Look at Mediterranean Lateen- and Square-Rigged Ships (Part 1)", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 37 (2): 347–359, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2008.00183.x

- Friedman, Zaraza; Zoroglu, Levent (2006), "Kelenderis Ship. Square or Lateen Sail?", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 35 (1): 108–116, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00091.x

- Günsenin, Nergis; Rieth, Éric (2012), "Un graffito de bateau à voile latine sur une amphore (IXe s. ap. J.-C.) du Portus Theodosiacus (Yenikapı)", Anatolia Antiqua 20: 157–164

- Makris, George (2002), "Ships", in Laiou, Angeliki E., The Economic History of Byzantium. From the Seventh through the Fifteenth Century, 1, Dumbarton Oaks, pp. 89–99, ISBN 978-0-88402-288-6

- Pomey, Patrice (2006), "The Kelenderis Ship: A Lateen Sail", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 35 (2): 326–335, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2006.00111.x

- Pryor, John H.; Jeffreys, Elizabeth M. (2006), The Age of the ΔΡΟΜΩΝ: The Byzantine Navy ca. 500–1204, Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-15197-0

- White, Lynn (1978), "The Diffusion of the Lateen Sail", Medieval Religion and Technology. Collected Essays, University of California Press, pp. 255–260, ISBN 978-0-520-03566-9, https://archive.org/details/medievalreligion00whit/page/255

- Whitewright, Julian (2009), "The Mediterranean Lateen Sail in Late Antiquity", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 38 (1): 97–104, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2008.00213.x

- Whitewright, Julian (2011). "The Potential Performance of Ancient Mediterranean Sailing Rigs". International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 40 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2010.00276.x.

- Whitewright, Julian (2012a). "Technological Continuity and Change: The Lateen Sail of the Medieval Mediterranean". Al-Masāq 24 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/09503110.2012.655580.

- Whitewright, Julian (2012b), "Early Islamic Maritime Technology", in Matthews, R.; Curtis, J.; Gascoigne, A. L., Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East. Volume 2: Ancient & Modern Issues in Cultural Heritage, Colour & Light in Architecture, Art & Material Culture, Islamic Archaeology, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, pp. 585–598

Further reading

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 174. ISBN 0393339181. https://archive.org/details/illustrateddicti00rous. ISBN:978-0393339185

- Rousmaniere, John (June 1998). The Illustrated Dictionary of Boating Terms: 2000 Essential Terms for Sailors and Powerboaters (Paperback). W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 174. ISBN 0393339181. https://archive.org/details/illustrateddicti00rous. ISBN:978-0393339185

External links

- The ship's development during the Middle Ages, see bottom of page for English translation

- PolySail International instructions for building a Sunfish-like lateen sail

- I. C. Campbell, "The Lateen Sail in World History", Journal of World History (University of Hawaii), 6.1 (Spring 1995), p. 1–23

|