Engineering:Diamond Princess (ship)

Diamond Princess anchored in Toba in December 2019

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Diamond Princess |

| Owner: | Carnival Corporation & plc |

| Operator: | Princess Cruises |

| Port of registry: |

|

| Builder: | Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

| Cost: | US$500 million |

| Yard number: | 2181 |

| Laid down: | 2 March 2002 |

| Launched: | 12 April 2003 |

| Christened: | 2004 |

| Completed: | 26 February 2004 |

| Maiden voyage: | 2004 |

| In service: | March 2004 |

| Identification: |

|

| Status: | Service suspended |

| Notes: | [1] |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Gem-class cruise ship |

| Tonnage: | 115,875 GT |

| Length: | 290.2 m (952 ft 1 in) |

| Beam: | 37.49 m (123 ft 0 in) |

| Height: | 62.48 m (205 ft 0 in) |

| Draught: | 8.53 m (28 ft 0 in) |

| Decks: | 13 |

| Installed power: | Wärtsilä 46 series common rail engines |

| Propulsion: | Twin propellers |

| Speed: | 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph) |

| Capacity: | 2,670 passengers |

| Crew: | 1,100 crew |

| Notes: | [1] |

Diamond Princess is a British-registered cruise ship owned and operated by Princess Cruises. She began operation in March 2004 and primarily cruises in Asia during the northern hemisphere summer and Australia during the southern hemisphere summer. She is a subclassed Grand-class ship, which is also known as a Gem-class ship. Diamond Princess and her sister ship, Sapphire Princess, are the widest subclass of Grand-class ships, as they have a 37.5-metre (123 ft 0 in) beam, while all other Grand-class ships have a beam of 36 metres (118 ft 1 in). Diamond Princess and Sapphire Princess were both built in Nagasaki, Japan, by Mitsubishi Industries.

There have been two notable outbreaks of infectious disease on the ship – an outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by norovirus in 2016 and an outbreak of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 in 2020. In the latter incident, the ship was quarantined for nearly a month with her passengers on board, and her passengers and crew were subject to further quarantine after disembarking. At least 712 out of the 3,711 passengers and crew were infected,[2] and by mid-April 2020 nine had died.[3][4]

Design and description

The diesel-electric plant of Diamond Princess has four diesel generators and a gas turbine generator. The diesel generators are Wärtsilä 46 series common rail engines, two straight 9-cylinder configuration (9L46), and two straight 8-cylinder configuration (8L46). The 8- and 9-cylinder engines can produce approximately 8,500 kW (11,400 hp) and 9,500 kW (12,700 hp), respectively. These engines are fueled with heavy fuel oil (HFO or bunker c) and marine gas oil (MGO) depending on the local regulations regarding emissions, as MGO produces much lower emissions, but is much more expensive.[citation needed]

The gas turbine generator is a General Electric LM2500, producing a peak of 25,000 kW (34,000 hp) fueled by MGO. This generator is much more expensive to run than the diesel generators, and is used mostly in areas, such as Alaska, where the emissions regulations are strict. It is also used when high speed is required to make it to a port in a shorter time period.[citation needed]

There are two propulsion electric motors, driving fixed-pitch propellers and six thrusters used during maneuvering – three at the bow and three at the stern. The propulsion electric motors (PEMs), are conventional synchronous motors made by Alstom Motors. The two motors are each rated to 20 MW and have a maximum speed of 154 rpm. (Rated speed of 0-145 rpm.)[citation needed]

In June 2017 Diamond Princess was retrofitted with a hull air lubrication system to reduce fuel consumption and related CO2 emissions.[5]

Construction and career

Diamond Princess was built in Japan by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, the first Princess Cruises ship to be built in a Japanese shipyard. Her only sister ship is Sapphire Princess, with whom she swapped names during construction. She and her sister ship were the largest cruise ships to be built by Mitsubishi since the Crystal Harmony in 1991.

The ship was originally intended to be christened Sapphire Princess. However, construction of another ship – the one intended to be Diamond Princess (currently sailing as Sapphire Princess) – was delayed when fire swept through her decks during construction. Because completion of the damaged ship would be delayed for some time, her sister ship, which was also under construction, was renamed Diamond Princess. The name swap helped keep the delivery of Diamond Princess on time.[6] Due to the fire and name swap, both vessels would be the last Carnival Corporation & plc vessels built by Mitsubishi until the completion of AIDAprima in 2016.[7]

She was the first Princess Cruises ship to be built in a Japanese shipyard, and the first to forego the controversial "wing" or "shopping cart handle" structure overhanging the stern, which houses the Skywalkers Nightclub on Caribbean Princess, Golden Princess and Star Princess, and which was originally also a feature of Grand Princess prior to her 2011 refit.[citation needed]

Prior to 2014, Diamond Princess alternated sailing north and southbound voyages of the glacier cruises during the northern summer months and in the southern summer, she sailed from Australia and New Zealand. Starting in 2014, she undertook cruises from Yokohama for Tokyo or Kobe in the northern summer season.[8]

For the 2016–17 season, she sailed round-trip cruises in the northern winter months from Singapore.[9] Kota Kinabalu was added as part of her destination along with Vietnamese port of Nha Trang in December 2016.[10] She resumed voyaging from Sydney for the 2017–18 season.[11]

After the 2018 Australia and New Zealand cruises, Diamond Princess was re-positioned into South-East Asia for most of 2018, varying between Japan, South Korea, Singapore, Vietnam, Taiwan and Malaysia.[12] She is projected to remain in South-East Asia to early 2021.[13] She is then projected go to South America and Antarctica in Fall 2021-Spring 2022.[14]

2016 gastroenteritis cases

In February 2016, Diamond Princess experienced a gastroenteritis outbreak, caused by norovirus sickening 158 passengers and crew on board, as confirmed after arrival in Sydney by NSW Health.[15]

On 20 January 2020, an 80-year-old passenger from Hong Kong embarked in Yokohama, sailed one segment of the itinerary, and disembarked in Hong Kong on 25 January. He visited a local Hong Kong hospital, six days after leaving the ship, where he later tested positive for COVID-19 on 1 February.[16] On its next voyage, 4 February, the ship was in Japanese waters when 10 passengers were diagnosed with COVID-19 during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.[17]

The ship was quarantined on 4 February[16] in the Port of Yokohama in Japan.[18] The infected included at least 138 from India (including 132 crew and 6 passengers), 35 Filipinos, 32 Canadians, 24 Australians, 13 Americans, 4 Indonesians, 4 Malaysians,[19] and 2 Britons.[20][21][22] Home countries arranged to evacuate their citizens and quarantine them further in their own countries. As of 1 March, all on board including the crew and the Italian captain Gennaro Arma had disembarked.[23]

As of 16 March, at least 712 out of the 3,711 passengers and crew had tested positive for the virus.[24][25] As of 14 April, fourteen of those who were on board had died from the disease.[26] On 30 March, the ship was cleared to sail again after the ship was cleaned and disinfected.[27][28][29]

On 16 May, Diamond Princess departed from the Port of Yokohama.[30] Japan ended up paying 94% of the medical expenses incurred by the Diamond Princess passengers.[31] All cruises throughout 2020 remained cancelled[32] and as of March 2021 the ship was bunkering in Malaysia and the outer port limit (OPL) area of Singapore Port.[33]

Quarantine!, a book written by passenger Gay Courter on her experience on board the quarantined vessel, was released in November 2020.[34][35] The HBO documentary The Last Cruise tells the story of the voyage.[26]

Airborne transmission likely accounted for >50% of disease transmission on the Diamond Princess cruise ship, which includes inhalation of aerosols during close contact as well as longer range. [36] With the application of the overall model (an ordinary differential equation-based Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Recovery (SEIR) model with Bayesian), basic reproductive number (R0) was estimated as high as 5.70 (95% credible interval: 4.23–7.79). [37]

The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in this cruise most likely originated from either a single person infected with a virus variant identical to the Wuhan WIV04 isolates, or simultaneously with another primary case infected with a virus containing the 11083G > T mutation. [38] [39] A total of 24 new viral mutations across 64.2% (18/28) of samples based on GISAID record, and the virus had evolved into at least five subgroups within 3 weeks.

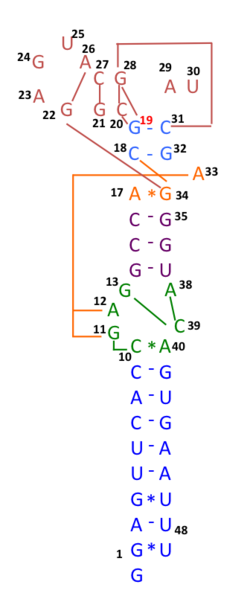

Increased positive selection of SARS-CoV-2 were statistically significant during the quarantine. Linkage disequilibrium analysis confirmed that RNA recombination with the 11083G > T mutation also contributed to the increase of mutations among the viral progeny. The findings indicate that the 11083G > T mutation of SARS-CoV-2 spread during shipboard quarantine and arose through de novo RNA recombination under positive selection pressure. In three patients in Diamond Princess cruise, two mutations, 29736G > T and 29751G > T (G13 and G28) were located in Coronavirus 3′ stem-loop II-like motif (s2m) of SARS-CoV-2. Although s2m is considered an RNA motif highly conserved in 3' untranslated region among many coronavirus species, this result also suggests that s2m of SARS-CoV-2 is RNA recombination/mutation hotspot. [40]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Advanced Masterdata for the Vessel Diamond Princess". VesselTracker. 2012. http://www.vesseltracker.com/en/Ships/Diamond-Princess-9228198.html.

- ↑ Feuer, William (28 March 2020). "CDC says coronavirus RNA found in Princess Cruise ship cabins up to 17 days after passengers left". CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/23/cdc-coronavirus-survived-in-princess-cruise-cabins-up-to-17-days-after-passengers-left.html.

- ↑ Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (14 April 2020). "横浜港で検疫を行ったクルーズ船に関連した患者の死亡について (About death of patient associated with cruise ship quarantined in Yokohama Port)" (in ja). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_10870.html.

- ↑ "How Dangerous is Covid-19?". 25 August 2020. https://www.hdruk.org/news/131952/.

- ↑ "Air lubrication system". 14 August 2018. http://www.seatrade-cruise.com/news/news-headlines/diamond-princess-retrofitted-with-silverstream-air-lubrication-system.html.

- ↑ "Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Cruise Ship Sapphire Princess To Be Delivered to Princess Cruises" (Press release). Hideo Ikuno, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. 26 May 2004. Archived from the original on 18 March 2014.

- ↑ "AIDAprima headed for Europe after Mitsubishi HI delivery". Seatrade Cruise News (Seatrade). 14 March 2016. http://www.seatrade-cruise.com/news/news-headlines/aidaprima-sails-for-europe-after-mitsubishi-hi-delivery.html. Retrieved 16 March 2016.

- ↑ "Princess Cruises Unveils 2015 Japan Cruise Program". http://www.princess.com/news/press_releases/2014/04/Princess-Cruises-Unveils-2015-Japan-Cruise-Program.html#.VaWlm_lViko.

- ↑ "Princess Cruises Debuts 2016–2017 Exotics Sailings". http://www.princess.com/news/press_releases/2015/05/Princess-Cruises-Debuts-2016-2017-Exotics-Sailings.html#.VaWnyPlViko.

- ↑ Elliott, Mark (2 December 2016). "Princess Cruises adds Kota Kinabalu to Asian season". Travel Asia Daily. http://www.traveldailymedia.com/244491/princess-cruises-adds-kota-kinabalu-to-asian-season/.

- ↑ "Emerald Princess cruise ship to debut in Sydney: Another cruise giant to call Australia home". 7 January 2015. http://www.traveller.com.au/emerald-princess-cruise-ship-to-debut-in-sydney-another-cruise-giant-to-call-australia-home-12jj1i.

- ↑ "Cruise Search Results:Princess Cruises" (in en). https://www.princess.com/find/searchResults.do?ship=DI.

- ↑ "Diamond Princess Cruises". https://www.seascanner.com/cruises-diamond-princess.

- ↑ Morgan Hines (18 August 2020). "Diamond Princess cruise ship, which had early COVID-19 outbreak, will sail in South America, Antarctica in 2021, 2022". USA Today. https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/cruises/2020/08/18/diamond-princess-cruise-ship-sail-south-america-antarctica/5601330002/.

- ↑ Brown, Michelle (4 February 2016). "Cruise ship hit by norovirus gastroenteritis docks in Sydney". ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)). http://www.abc.net.au/news/2016-02-04/gastro-outbreak-hits-158-aboard-luxury-cruise-liner-in-sydney/7138950.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Updates on Diamond Princess". Princess. https://www.princess.com/news/notices_and_advisories/notices/diamond-princess-update.html. Entries from 1 to 27 February 2020

- ↑ Peel, Charlie; Snowden, Angelica (6 February 2020). "Coronavirus: Cases double on Diamond Princess overnight, still in lockdown". The Australian. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/world/coronavirus-ten-confirmed-cases-on-diamond-princess-cruise-ship/news-story/aa92fa119c19384e4c50c36eee185553.

- ↑ Thompson, Julia; Yasharoff, Hannah. "Coronavirus cases on Diamond Princess soar past 500, site of most infections outside China" (in en-US). https://www.usatoday.com/story/travel/cruises/2020/02/18/coronavirus-jose-andres-provides-meals-diamond-princess-passengers/4788804002/.

- ↑ Perimbanayagam, Kalbana (18 February 2020). "Dr Dzulkefly: Only four Malaysians on board Diamond Princess". New Straits Times. https://www.nst.com.my/news/nation/2020/02/566769/dr-dzulkefly-only-four-malaysians-board-diamond-princess.

- ↑ Fraser, Ted (17 February 2020). "Number of Canadians on Diamond Princess testing positive for COVID-19 virus rises to 32" (in en). The Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/gta/2020/02/17/32-canadians-on-diamond-princess-cruise-ship-test-positive-for-covid-19.html.

- ↑ Bangkok, Justin McCurry Rebecca Ratcliffe in (18 February 2020). "British couple on Diamond Princess question positive coronavirus test" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2020/feb/18/britain-to-evacuate-citizens-from-coronavirus-hit-cruise-ship-diamond-princess.

- ↑ Allman, Daniel; Silverman, Hollie; Toropin, Konstantin. "13 Americans moved to Omaha facility from evacuation flights, US officials say". https://www.cnn.com/2020/02/17/health/evacuated-passengers-test-positive-coronavirus/index.html.

- ↑ "All crew members have left virus-hit ship in Japan: Minister". News24. 1 March 2020. https://www.news24.com/World/News/all-crew-members-have-left-virus-hit-ship-in-japan-minister-20200301.

- ↑ "新型コロナウイルス感染症の現在の状況と厚生労働省の対応について(令和2年3月17日版)" (in ja). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_10251.html.

- ↑ "クルーズ船感染者数696人に訂正 厚労省" (in ja). 5 March 2020. https://www.sankei.com/life/news/200305/lif2003050076-n1.html.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hannah Sampson (April 1, 2021). "'Afraid we would never see our families again': HBO documentary highlights agony of Diamond Princess crew". The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2021/04/01/diamond-princess-hbo-documentary-covid/.

- ↑ Clarke, Patrick (1 April 2020). "Diamond Princess Cleared to Sail Following Thorough Cleaning". travelpulse.com. https://www.travelpulse.com/news/cruise/diamond-princess-cleared-to-sail-following-thorough-cleaning.html.

- ↑ "横浜港で検疫を行ったクルーズ船に関連した患者の死亡について" (in ja). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_10802.html.

- ↑ "横浜港で検疫を行ったクルーズ船に関連した患者の死亡について" (in ja). https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/newpage_10870.html.

- ↑ "「ダイヤモンド・プリンセス」が横浜港を出港 マレーシアへ". NHK. 16 May 2020. https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20200516/k10012433121000.html.

- ↑ "Japan paid 94% of medical costs for foreign passengers on coronavirus-hit cruise ship". November 12, 2020. https://the-japan-news.com/news/article/0006922538.

- ↑ "Carnival's North American Brands Cancel Sailings Until 2021". https://www.travelpulse.com/news/cruise/carnivals-north-american-brands-cancel-sailings-until-2021.html.

- ↑ "DIAMOND PRINCESS, Passenger (Cruise) Ship - Details and current position - IMO 9228198 MMSI 235103359 - VesselFinder". https://www.vesselfinder.com/vessels/DIAMOND-PRINCESS-IMO-9228198-MMSI-235103359.

- ↑ Arradondo, Briona (2020-11-12). "Author details first months of pandemic spent on cruise ship, in quarantine" (in en-US). https://www.fox13news.com/news/author-details-first-months-of-pandemic-spent-on-cruise-ship-in-quarantine.

- ↑ Courter, Gay (2020-11-11). "New book relives Diamond Princess Covid catastrophe" (in en-US). https://asiatimes.com/2020/11/new-book-relives-diamond-princess-covid-catastrophe/.

- ↑ "Mechanistic transmission modeling of COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess cruise ship demonstrates the importance of aerosol transmission". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 118 (8): e2015482118. 23 February 2021. doi:10.1073/pnas.2015482118. PMID 33536312.

- ↑ "The Bayesian Susceptible-Exposed-Infected-Recovered model for the outbreak of COVID-19 on the Diamond Princess Cruise Ship". Stoch Environ Res Risk Assess. 35 (7): 1319–1333. 26 January 2021. doi:10.1007/s00477-020-01968-w. PMID 33519302.

- ↑ "Faster de novo mutation of SARS-CoV-2 in shipboard quarantine". Bull World Health Organ. 99 (7): 496–505. 6 April 2020. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.273227. PMID 34248222. PMC 8243036. https://www.who.int/bulletin/online_first/20-255752.pdf.

- ↑ "Haplotype networks of SARS-CoV-2 infections in the Diamond Princess cruise ship outbreak". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117 (33): 20198–20201. 18 August 2020. doi:10.1073/pnas.2006824117. PMID 32723824.

- ↑ "Viral transmission and evolution dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 in shipboard quarantine". Bull World Health Organ. 99 (7): 486–495. 1 July 2021. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.273227. PMID 34248222.

External links