Engineering:Tupolev Tu-22

| Tu-22 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Tu-22PD | |

| Role | Medium bomber |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Tupolev |

| First flight | 7 September 1959 |

| Introduction | 1962 |

| Retired | Early 2000s (Libya) |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary users | Soviet Air Force Ukrainian Air Force Libyan Air Force Iraqi Air Force |

| Produced | 1960–1969 |

| Number built | 311 |

| Developed into | Tupolev Tu-22M |

The Tupolev Tu-22 (Air Standardization Coordinating Committee name: Blinder) was the first supersonic bomber to enter production in the Soviet Union. Manufactured by Tupolev, the Tu-22 entered service with Long-Range Aviation and Soviet Naval Aviation in the 1960s.

The aircraft was a disappointment, lacking both the speed and range that had been expected. It was also a difficult design to fly and maintain. It was produced in small numbers, especially compared to the Tupolev Tu-16 it was designed to replace. The aircraft was later adapted for other roles, notably as the Tu-22R reconnaissance aircraft and as a carrier for the long-range Kh-22 antiship missile.

Tu-22s were sold to other nations, including Libya and Iraq. The Tu-22 was one of the few Soviet jet bombers to see combat: Libyan Tu-22s were used against Tanzania and Chad, and Iraqi Tu-22s were used during the Iran–Iraq War.

Development

Previous efforts

Andrei Tupolev's OKB-156 had successfully converted the Boeing B-29 Superfortress into the Tupolev Tu-4, while their suggestions to create a more advanced design were ignored as they fell from favour. In 1951, Stalin created OKB-23 under the direction of Vladimir Mikhailovich Myasishchev to build new long-range bomber designs, forming the bureaus by picking designers out of Tupolev's OKB-156. OKB-23 began development of the four-engined Myasishchev M-4 intercontinental jet bomber.[1]

To keep themselves in the bomber field, OKB-156 designed their own entry for a jet-powered bomber, the twin-engined Tupolev Tu-16 medium bomber.[2] They were aware that the range of the design would not be enough to fill the intercontinental role of the M-4, and for this mission, they also proposed the four-turboprop Tupolev Tu-95. Ultimately neither the M-4 nor Tu-16 met their range requirements, leaving only the Tu-95 really able to carry out attacks against the US, with more limited performance. The M-4 was built only in small numbers, while the Tu-16 had much more widespread uses in a variety of roles.[3]

Supersonic replacements

All of these aircraft were still being introduced when the State Committee for Aviation Technology (soon to become the Ministry of Aircraft Production, or MAP) announced a contest for supersonic designs that would replace all previous designs. Tupolev's chief designer, Sergey Mikhailovitch Yeger, was determined not to lose to Myasishchev once again.[1]

They quickly proposed a new design, Samolyot 103 (Plane 103). This was essentially a Tu-16 with four much more powerful engines, either Dobrynin VD-7s or Mikulin AM-13s.[1] However, experience on the experimental Samolyot 98 tactical bomber design suggested that the 103 would not have supersonic performance. They decided to start over with a blank-sheet design.[2]

After considering many possible solutions from TsAGI, Yeger eventually settled on what became Samolyot 105 in 1954.[1] Among its features was the selection of a single pilot with no copilot, which allowed the cockpit to be narrower, as only one person had to be seated forward to see the runway. This had positive political aspects as it reduced crew size to three.[2][further explanation needed]

Myasishchev was also working to fulfill the requirement with his much larger Myasishchev M-50. It was designed to have intercontinental range, filling the role for which the M-4 was intended. Both the Tupolev and Myasishchev designs were approved for prototype production in 1954.[2]

At the time, supersonic aerodynamics were still in their infancy, as were the engines that would power the designs. By this point, three engine models were being considered for the 105: the VD-5, the VD-7, and the new Kuznetsov NK-6. Of the three, the NK-6 offered the best performance, but was still in the initial stages of development.[2] As the engines possibly would not meet their goals and leave the 105 underpowered, much attention was spent on cleaning up the aerodynamics to reach the required speed. This was notable in the design of the wing and landing gear, which were designed to be as "clean" as possible, with the main wheels retracting into the fuselage to allow the wing to be thinner.[2]

Around the same time, LII wind tunnel experiments revealed a tendency for aircraft to pitch up around Mach 1.[lower-alpha 1] This led to the decision to move the engines from the wing roots, as in the Tu-16, to an unconventional external tail-mounted position, on either side of the vertical stabilizer. This location also reduced drag and inlet losses.

The wings were highly swept, between 52 and 55° to give little drag at transonic speeds, which led to poor take-off performance and high landing speeds.[4]

Prototypes

The first prototype 105 was completed and shipped to the Flight Test and Development Base at Zhukovsky in August 1957. It flew for the first time on 21 June 1958, flown by test pilot Yuri Alasheev.[5][6] Initial flights quickly demonstrated that the design had neither the speed nor range that was expected. Around this time, TsAGI independently discovered the area rule for minimizing transonic aerodynamic drag, and this design was applied to 105. A key problem was that the wing root was too thick to properly exploit this effect and to further thin it, a new landing-gear design was introduced,[further explanation needed] along with several more changes to the layout of the cabin and tail areas.[7]

The result of all of these changes was the 105A, which first flew on 7 September 1959.[8] Serial production of 20 examples was issued around this time, even before testing had completed. The first serial-production Tu-22B bomber, built by Factory No. 22 at Kazan, flew on 22 September 1960,[9] and the type was presented to the public in the Tushino Aviation Day parade on 9 July 1961, with a flypast of 10 aircraft.[10] It initially received the NATO reporting name 'Bullshot', which was deemed to be inappropriate, then 'Beauty', which was deemed to be too complimentary, and finally the 'Blinder'. Soviet crews called it "shilo" (awl) because of its shape.[9]

Into service

The Tu-22 entered service in 1962,[9] but it experienced a considerable number of problems, resulting in widespread unserviceability and several crashes. Amongst its many faults was a tendency for aerodynamic heating of the aircraft skin at supersonic speed, distorting the control rods and causing poor handling. The landing speed was 100 km/h (62 mph) greater than of the previous bombers and the Tu-22 had a tendency to pitch up and strike its tail on landing – though this problem was eventually resolved with the addition of electronic stabilization aids. Even after some of its problems had been resolved, the Blinder was not easy to fly, and was maintenance-intensive. Among its unpleasant characteristics was a wing design that allowed aileron reversal at high speeds. When the stick had been neutralized following such an event, the deformation of the wing did not necessarily disappear, but could persist and result in an almost uncontrollable aircraft.[citation needed]

Pilots for the first Tu-22 squadrons were selected from the ranks of "First Class" Tu-16 pilots, which made transition into the new aircraft difficult, as the Tu-16 had a co-pilot, and many of the "elite" Tu-16 pilots selected had become accustomed to allowing their co-pilots to handle all the flight operations of the Tu-16 except for take-offs and landings. As a consequence, Tu-16 pilots transitioning to the single-pilot Tu-22 suddenly found themselves having to perform all the piloting tasks, and in a much more complicated cockpit environment. Many, if not most, of these pilots were unable to complete their training for this reason. Eventually, pilots were selected from the ranks of the Su-17 "Fitter" crews, and these pilots made the transition with less difficulty.[citation needed]

Variants

By the time the Tu-22B (Blinder-A) entered service, its operational usefulness had been found to be limited. Despite its speed, it was inferior to the Tu-16 with respect to combat radius, weapon load, and serviceability. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev believed that ballistic missiles were the way of the future, and bombers like the Tu-22 were in danger of cancellation.[11] As a result, only 15[9] (some sources say 20) Tu-22Bs were built.

While the Tu-22 was being introduced, the Strategic Rocket Forces branch was created in 1959, and Tupolev, along with other project backers, understood that manned bombers were falling out of favor as a means of delivering nuclear weapons.[7] To save the program, Tupolev proposed a long-range aerial reconnaissance version of the aircraft, which could be modified in the field to return it to a bombing role.[12]

The resulting combat-capable Tu-22R (Blinder-C) entered service in 1962. The Tu-22R could be fitted with an aerial refueling probe that was subsequently fitted to most Tu-22s, expanding their radius of operation; 127 Tu-22Rs were built, 62 of which went to the Soviet Naval Aviation (AVMF) for maritime patrol use.[13] Some of these aircraft were stripped of their cameras and sensor packs and sold for export as Tu-22Bs, although in other respects, they apparently remained more comparable to the Tu-22R than to the early-production Tu-22Bs.[14]

A trainer version of the Blinder, the Tu-22U (Blinder-D), was fielded at the same time; it had a raised second cockpit for an instructor pilot. The Tu-22U had no tail guns, and was not combat-capable; 46 were produced.[15]

To try to salvage some offensive combat role for the Tu-22 in the face of official hostility, the Tu-22 was developed as a missile carrier, the Tu-22K (Blinder-B), with the ability to carry a single Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) stand-off missile in a modified weapons bay. The Tu-22K was deployed both by Long Range Aviation and AVMF.[16]

The last Tu-22 subtype was the Tu-22P (Blinder-E) electronic warfare version, initially used for electronic intelligence gathering. Some were converted to serve as stand-off electronic countermeasure jammers to support Tu-22K missile carriers. One squadron was usually allocated to each Tu-22 regiment.[17]

The Tu-22 was upgraded in service with more powerful engines, in-flight refueling (for those aircraft that did not initially have it), and better electronics. The -D suffix (for Dalni, long-range) denotes aircraft fitted for aerial refueling.

Tu-22s were exported to Iraq and Libya during the 1970s. An Egyptian request was refused as a result of Soviet objections to the Yom Kippur War.[14]

Design

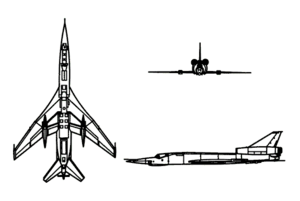

The Tu-22 has a low-middle mounted wing swept at an angle of 55°.[18] The two large turbojet engines, originally 159 kN (36,000 lbf) Dobrynin VD-7M, later 162 kN (36,000 lbf) Kolesov RD-7M2,[19] are mounted atop the rear fuselage on either side of the large vertical stabilizer, with a low-mounted tailplane. Continuing a Tupolev OKB design feature, the main landing gear are mounted in pods at the trailing edge of each wing. The highly swept wings gave little drag at transonic speeds, but resulted in very high landing speeds and a long take-off run.[20][21] This limited the design to "first-class airfields", those with runways at least 3,000 m (9,800 ft) long.[4]

The Tu-22's cockpit placed the pilot forward, offset slightly to the left, with the weapons officer behind and the navigator below, within the fuselage, sitting on downwards-firing ejector seats. The downward direction meant the minimum altitude for ejection was 350 m (1,150 ft), which precluded their use during take-off and landing, when most accidents occur. The crew entered the plane by lowering the seats on rails and then climbing external stepladders, sitting in the seats, and then being cranked upward into the cockpit.[18]

The cockpit layout was also criticized by the pilots; it was filled with levers and handles that gained it comparisons to a hedgehog, and some of those controls could not be reached by the pilots, who took to flying with metal hooks and other ad hoc devices. Adding to its problems was a very high panel on the right, which blocked the view of the runway during landing if the aircraft had to crab against a wind from the left. This led to it being forbidden for flight by new pilots in crosswind conditions above fresh breeze on the Beaufort scale.[18][22]

Air for the crew was provided by a bleed air system on the engine compressors. This air was hot and had to be cooled before being pumped into the cockpit. This cooling was provided by a large total-loss evaporator running on a mixture of 40% ethanol and 60% distilled water (effectively vodka). This system garnered the aircraft one of its many nicknames, the "supersonic booze carrier". As the system vented the coolant after use, the aircraft could run out during flight, and comfort had to be balanced by the possibility of running out of coolant.[23] Numerous cases of Tu-22 crews drinking the coolant mixture and becoming paralytically drunk led to a crackdown by Soviet Air Force authorities. Access to the bombers after flights was restricted, and more frequent checks were made on coolant levels. This higher level of security, however, did not end the practice.

The Tu-22's defensive armament, operated by the weapons officer, consisted of a remotely controlled tail turret beneath the engine pods, containing a single 23 mm (0.906 in) R-23 gun.[24] The turret was directed by a small PRS-3A Argon gun-laying radar due to the weapons officer's total lack of rear visibility (and generally much more accurate and precise fire control than optical aiming).[8] The bomber's main weapon load was carried in a fuselage bomb bay between the wings, capable of carrying a variety of free-fall weapons – up to 24 FAB-500 general-purpose bombs, one 9,000 kg (20,000 lb) FAB-9000 bomb, or various nuclear bombs.[9] On the Tu-22K, the bay was reconfigured to carry one Raduga Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) missile semirecessed beneath the fuselage. The enormous weapon was big enough to have a substantial effect on handling and performance, and was also a safety hazard.[25]

The early Tu-22B had an optical bombing system (which was retained by the Tu-22R), with a Rubin-1A navigation/attack radar.[15] The Tu-22K had the Leninets PN (NATO reporting name 'Down Beat') to guide the Kh-22 missile.[25] The Tu-22R could carry a camera array or an APP-22 jammer pack in the bomb bay as an alternative to bombs.[15] Some Tu-22Rs were fitted with the Kub ELINT system, and later with an under-fuselage pallet for M-202 Shompol side-looking airborne radar, as well as cameras and an infrared line scanner. A few Tu-22Ks were modified to Tu-22KP or Tu-22KPD configuration with Kurs-N SIGINT equipment to detect enemy radar systems and provide compatibility with the Kh-22P antiradiation missile.[19]

Operational history

Libya

The Libyan Arab Republic Air Force used the Tu-22 in combat against Tanzania in 1979 as part of the Uganda–Tanzania War to help its Ugandan allies, with a single Tu-22 flying a completely unsuccessful bombing mission against Mwanza on 29 March 1979.[26]

The Libyan aircraft were also used against Chad as part of the Chadian–Libyan conflict, with strikes into western Sudan and Chad. Libyan Tu-22s flew their first mission over Chad on 9 October 1980 against Hissène Habré's forces near the Chadian capital of N'Djamena.[14][27] Occasional bombing raids by small numbers of Tu-22s against targets in Chad and Sudan, including a raid on Omdurman in September 1981, which killed three civilians and injured 20 others, continued to be performed until a ceasefire was arranged in November 1981.[28]

Fighting restarted in July 1983, with Libyan air power, including its Tu-22s, being used in attacks against forces loyal to Habré, before a further ceasefire stopped the fighting until Libyan-assisted forces began a fresh offensive in early 1986. On 17 February 1986, in retaliation for the French Operation Épervier (which had hit the runway of the Libyan Ouadi Doum Airbase one day earlier), a single Tu-22B attacked the airfield at N'Djamena. Staying under French radar coverage by flying low over the desert for more than 1,100 km (700 mi), it accelerated to over Mach 1, climbed to 5,000 m (16,500 ft) and dropped three heavy bombs. Despite the considerable speed and height, the attack was extremely precise; two bombs hit the runway, one demolished the taxiway, and the airfield remained closed for several hours as a consequence.[29][30] The bomber ran into technical problems on its return journey. U.S. early warning reconnaissance planes based in Sudan monitored distress calls sent by the pilot of the Tu-22 that probably crashed before reaching its base at Aouzou (maybe hit by antiaircraft guns that fired in N'Djamena airport).[31] On 19 February, another LARAF Tu-22 attempted to bomb N'Djamena once again. Libyan sources have claimed that this attempt was spoiled when the Tu-22 was detected while approaching N'Djamena, and two Mirage F1s were scrambled to intercept it. However, French officers present in Chad don't recall any contact with Libyan aircraft on that day.[32] One bomber was shot down by captured 2K12 Kub (SA-6) surface-to-air missiles during a bombing attack on an abandoned Libyan base at Aouzou on 8 August 1987.[33][19] One eyewitness report suggests that the pilot ejected, but his parachute was seen on fire.

Another Blinder was lost on the morning of 7 September 1987, when two Tu-22Bs conducted a strike against N'Djamena. A French battery of MIM-23 Hawk SAMs of the 402nd Air Defence Regiment shot down one of the bombers, killing the East German crew.[34][35] This raid was the last involvement of the Tupolev Tu-22 with the Chadian–Libyan conflict.

The last flight of a Libyan Blinder was recorded on 7 September 1992. They are probably now unserviceable because of a lack of spare parts, although seven are visible at the Al Jufra Air Base at [ ⚑ ] 29°11′58.18″N 16°00′26.17″E / 29.1994944°N 16.0072694°E. They were reportedly replaced by Su-24s.[36]

Iraq

Iraq used its Tu-22s in the Iran–Iraq War from 1980 to 1988. Offensive operations started on the first day of the war, when a Tu-22 based at H-3 Air Base struck an Iranian fuel depot at Mehrabad International Airport, Tehran, which in conjunction with other Iraqi attacks resulted in a shortage of aviation fuel for the Iranians in the early period of the war.[37] Otherwise, these early attacks were relatively ineffective, with many raids being aborted owing to Iranian air defences and operations being disrupted by heavy Iranian air strikes against Iraqi airfields.[38] Iran claimed three Tu-22s shot down during October 1980, one on 6 October over Tehran, and two on 29 October, one near Najafabad by an AIM-54 Phoenix missile launched by an F-14 interceptor and one over Qom.[39]

Iraq deployed its Tu-22s during the War of the Cities (along with Tu-16s, Su-22s and MiG-25s), flying air-raids against Tehran, Isfahan and Shiraz, with these attacks supplemented by Iraqi Scud and Al Hussein missiles. Iran retaliated against Iraqi cities with its own Scuds.[40][41] The Iraqi Air Force were particularly enthusiastic users of the gargantuan 9,000 kg (20,000 lb) FAB-9000 general-purpose bomb, which skilled Tu-22 pilots could deploy with impressive accuracy, using supersonic toss bombing techniques at stand-off distances and allowing the aircraft to escape retaliatory anti-aircraft fire. Usage of the FAB-9000 was so heavy that the Iraqis ran low of imported Soviet stocks and resorted to manufacturing their own version, called the Nassir-9.[35]

Iraqi Tu-22s were also deployed in the last stages of the "Tanker War". On 19 March 1988, four Tu-22s together with six Mirage F.1s carried out a raid against Iranian oil tankers near Kharg Island. The Tu-22s sank one supertanker and set another on fire, while Exocet missiles from the Mirages damaged another tanker.[27][42] A second strike against Kharg Island later that day was less successful, encountering alerted Iranian defences, with two Tu-22s being shot down. These were the final operations carried out by Iraq's Tu-22s during the Iran–Iraq war. Iraq lost seven Tu-22s during the war, with several more badly damaged.[27][42] The remaining Iraqi Tu-22s were destroyed by American air attacks during the 1991 Gulf War.[43]

Soviet Union

The only Soviet combat use of the Tu-22 occurred in 1988, during the Soviet withdrawal from the war in Afghanistan. Tu-22P Blinder-E electronic jammers were given the task of covering the withdrawal route back to the Soviet Union. Radar-jamming Tu-22PD aircraft covered Tu-22M3 Backfire-C bombers operating from the Mary-2 airfield in the Turkmen SSR on missions in Afghanistan near the Pakistan i border. They protected the strike aircraft against Pakistani F-16 air defence activity and suppressed radar systems, which could aid Pakistani F-16 attacks on the Soviet bombers in the border region.[44] Tu-22PD crews were also tasked with photoreconnaissance missions, to assess bomb damage, in addition to their primary electronic warfare missions.[45]

The Tu-22 was gradually phased out of Soviet service in favor of the more-capable Tupolev Tu-22M. At the time of the dissolution of the Soviet Union, 154 remained in service, but none are now believed to be used.[citation needed]

Variants

In total, 311 Tu-22s of all variants were produced, the last in 1969. Production numbers were: 15 of bomber version (B), about 127 of reconnaissance versions (R, RD, RK, RDK and RDM), 47 of ELINT versions (P and PD), 76 of missile carriers (K, KD, KP and KPD) and 46 of training versions (U and UD).

- Tu-22B (Blinder-A)

- Original free-fall bomber variant – only 15 built, ultimately used mostly for training or test purposes.The 12 aircraft have since passed away, but as of 2023, three still exist and are on display in museums across Russia.

- Tu-22A

- Export type based on bomber type. Ten aircraft were exported to Iraq and 14 to Libya.It is also called Tu-22B in some documents.

- Tu-22M

- The Tupolev Tu-22M was a distinct design with variable-sweep wings and not actually a variant of Tu-22; it was designated so largely for political reasons.

- Tu-22R (Blinder-C)

- Reconnaissance aircraft, retaining bombing capability

- Tu-22RD

- Version of Tu-22R with refueling equipment

- Tu-22RK

- Reconnaissance aircraft, retaining bombing capability and fitted with Kub ELINT systems during the 1970s

- Tu-22RDK

- Version of Tu-22RK with refueling equipment

- Tu-22RDM

- Upgraded reconnaissance version, converted from earlier RD aircraft in the early 1980s, with instruments in a detachable container

- Tu-22P (Blinder-E)

- Electronic warfare version

- Tu-22PD

- Version of Tu-22P with refueling equipment

- Tu-22K (Blinder-B)

- Missile-carrier version built from 1965, equipped to launch the Raduga Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) missile

- Tu-22KD

- Version of Tu-22K with refueling equipment

- Tu-22KP

- Electronic warfare / bomber version, introduced circa 1968, carrying the Kh-22P antiradiation missile

- Tu-22KPD

- Version of Tu-22KP with refueling equipment.

- Tu-22U (Blinder-D)

- Trainer version

- Tu-22UD

- Version of Tu-22U with refueling equipment

Operators

Libya

Libya

- Libyan Air Force (1951-2011) – received 14 Tu-22As and 2 Tu-22UDs. Retired due to lack of spare parts in early 2000s.

- Iraqi Air Force – received 10 Tu-22Bs, 2 Tu-22Us, and 4 Tu-22Ks. All destroyed during the Iran–Iraq War and Gulf War.

- 36th Squadron[46]

Russia

Russia

- Russian Air Force – retired, 10 in reserve.

- Russian Naval Aviation – retired

Ukraine

Ukraine

- Ukrainian Air Force – retired

- Ukrainian Naval Aviation – retired

- 1 Tu-22KD in the Poltava Museum of Long-Range and Strategic Aviation.[47]

Soviet Union

Soviet Union

- Soviet Air Forces – aircraft were transferred to Russian and Ukrainian Air Forces after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

- 121st Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment, military unit 15486 (Machulishchi), operation from 1964 to 1994.

- 203rd Guards Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment, military unit 26355 (Baranovichi), operation from 1962 to 1994.

- 303rd Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment, Zavitinsk (air base)

- 341st Heavy Bomber Aviation Regiment, military unit 27882, Ozernoye Air Base,[48] from 1965 to 1997

- 199th ODRAP military unit 13656 Nezhin, from 1965 to 1998

- 290th ODRAP military unit 65358 in Zyabrovka. Operation 1964 to 1994

- Aviation training center, military unit 65358-U (Zyabrovka). A separate training aviation squadron under central command (from 1986 to the end) did not have its own aircraft.

- 444th TBAP, Vozdvizhenka. The regiment was retrained in 1968 on the Tu-22, six aircraft were received. According to the decision of the General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces, at the last moment the rearmament of the regiment was stopped, the resulting aircraft were transferred to other units, and the regiment returned to operating the Tu-16.

- 6212th aviation equipment liquidation base, military unit 25855, Engels. Tu-22 cutting since 1993.

- Soviet Naval Aviation

- 30th Independent Long-Range Aviation Regiment (ODRAP) Air Force Black Sea Fleet military unit 56126, Saki-4, then Oktyabrskoye. Operation of the Tu-22 from 1965 to 1993. Then the regiment was reorganized into the 198th separate long-range reconnaissance aviation squadron (12 crews). The squadron was disbanded in 1995.

- 15th ODRAP Air Force Baltic Fleet military unit 49206 (Chkalovsk). From 1962 to June 1989. Then the regiment retrained on the Su-24.

Specifications (Tu-22R)

Data from Combat Aircraft since 1945[49]

General characteristics

- Crew: 3 (pilot, navigator, weapons officer)

- Length: 41.6 m (136 ft 6 in)

- Wingspan: 23.17 m (76 ft 0 in)

- Height: 10.13 m (33 ft 3 in)

- Wing area: 162 m2 (1,740 sq ft)

- Airfoil: TsAGI SR-5S[50]

- Gross weight: 85,000 kg (187,393 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 92,000 kg (202,825 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Dobrynin RD-7M-2 afterburning turbojet engines, 107.9 kN (24,300 lbf) thrust each dry, 161.9 kN (36,400 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,510 km/h (940 mph, 820 kn)

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.42

- Range: 4,900 km (3,000 mi, 2,600 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 13,300 m (43,600 ft)

- Rate of climb: 12.7 m/s (2,500 ft/min)

- Wing loading: 525 kg/m2 (108 lb/sq ft)

- Thrust/weight: 0.39

Armament

- Guns: 1 × R-23 23 mm cannon in tail turret

- Missiles: 1 × Kh-22 (AS-4 Kitchen) cruise missile

- Bombs: 12,000 kg (26,500 lb) capacity

- 24 × FAB-500 bombs or

- 1 × FAB-9000 bomb

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Notes

- ↑ This is due to the movement of shock waves as the aircraft approaches and crosses Mach 1. As these move over the various surfaces, they can cause nose-up or -down trim depending on the exact layout of the aircraft.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Burdin & Dawes 2006, pp. 13, 14.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 15.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Duffy & Kandalov 1996, p. 124.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Zaloga 1998, p. 60.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Zaloga 1998, p. 61.

- ↑ Gunston 1961, p. 109.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 18.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Zaloga 1998, p. 81.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Zaloga 1998, p. 63.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 63–66.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 66–67.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Duffy & Kandalov 1996, p. 123.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Zaloga 1998, p. 80.

- ↑ Duffy & Kandalov 1996, pp. 123–125.

- ↑ Gunston 1995, pp. 430–431.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 67, 78.

- ↑ Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 217.

- ↑ "Tu-22 BLINDER (TUPOLEV)". FAS WMD Resources. Federation of American Scientists. 8 August 2000. https://fas.org/nuke/guide/russia/bomber/tu-22.htm.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Zaloga 1998, pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995a, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, p. 53.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, p. 54.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 81–82.

- ↑ "Raiding Libyan jet may have crashed; France sends troops, planes to Chad". Ottawa Citizen: p. A7. 18 February 1986. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=2194&dat=19860218&id=XDg0AAAAIBAJ&pg=1356,3416676.

- ↑ Cooper, Grandolini & Delalande 2016, p. 46

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, p. 55.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, p. 82.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, p. 56.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995a, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995a, pp. 64, 66.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995a, p. 66.

- ↑ Zaloga 1998, pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Perrimond, Guy (2002). "The threat of theatre ballistic missiles: 1944–2001". TTU Europe. http://www.ttu.fr/site/english/endocpdf/24pBalmissileenglish.pdf. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Cooper & Bishop 2004, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Cooper, Bishop & Hubers 1995b, p. 57.

- ↑ Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 185.

- ↑ Burdin & Dawes 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ Woods, Kevin M.; Murray, Williamson; Nathan, Elizabeth A.; Sabara, Laila; Venegas, Ana M. (2011). Saddam's Generals: Perspectives of the Iran-Iraq War. Institute for Defense Analyses. p. 195. ISBN 9780160896132. https://archive.org/details/saddamsgeneralsp00alex/page/195.

- ↑ "Музей дальней авиации, Полтава" (in uk). doroga.ua. 2007. http://www.doroga.ua/poi/Poltavskaya/Poltava/Muzej_daljnej_aviacii/1304.

- ↑ http://www.ww2.dk/new/air%20force/regiment/bap/341tbap.htm

- ↑ Wilson, Stewart (2000). Combat Aircraft Since 1945. Fyshwick, Australia: Aerospace Publications. p. 138. ISBN 1-875671-50-1.

- ↑ Lednicer, David (15 September 2010). "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". Applied Aerodynamics Group, Department of Aerospace Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign. https://m-selig.ae.illinois.edu/ads/aircraft.html.

Bibliography

- Burdin, Sergey; Dawes, Alan E. (2006). Tupolev Tu-22 Blinder. Barnsley, UK: Pen and Sword Aviation. ISBN 978-1-84415-241-4.

- Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad; Hubers, Arthur (1995a). "Bombed by 'Blinders': Tupolev Tu-22s in Action – Part One". Air Enthusiast (Stamford, UK: Key Publishing) (116, March/April): 56–66. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad; Hubers, Arthur (1995b). "Bombed by 'Blinders': Tupolev Tu-22s in Action – Part Two". Air Enthusiast (Stamford, UK: Key Publishing) (117, May/June): 46–57. ISSN 0143-5450.. Also published as: Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad; Hubers, Arthur (5 December 2010). "Bombed by Blinders – Part 2". http://www.acig.info/CMS/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=249&Itemid=47..

- Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad (2004). Iranian F-14 Tomcat Units in Combat. Oxford, UK: Osprey Limited. pp. 79–80. ISBN 1-84176-787-5.

- Cooper, Tom; Bishop, Farzad (2000). Iran-Iraq War in the Air. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 0-7643-1669-9.

- Cooper, Tom; Grandolini, Albert; Delalande, Arnaud (2016). Libyan Air Wars. Part 2: 1985-1986. Helion & Company Publishing. ISBN 978-1-910294-53-6.

- Delalande, Arnaud; Cooper, Tom (2017). "An Eye for an Eye: The Libyan Arab Air Force's Tupolev Tu-22 Blinders in Combat in Chad, 1981–1987". The Aviation Historian (20): 26–35. ISSN 2051-1930.

- Duffy, Paul; Kandalov, Andrei (1996). Tupolev The Man and His Aircraft. Shrewsbury, UK: Airlife Publishing. ISBN 1-85310-728-X.

- Gunston, Bill (27 July 1961). "Russian Revelations: New Aircraft Seen at Tushino on July 9". Flight: 109–112. http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1961/1961%20-%201009.html.

- Gunston, Bill (1995). The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft 1875–1995. London: Osprey. ISBN 1-85532-405-9.

- Healey, John K. (January–February 2004). "Retired Warriors: 'Cold War' Bomber Legacy". Air Enthusiast (109): 75–79. ISSN 0143-5450.

- Williams, Anthony G.; Gustin, Emmanuel (2004). Flying Guns: The Modern Era. Ramsbury, UK: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-655-3.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (1998). "Tupolev Tu-22 'Blinder' and Tu-22M Backfire". World Air Power Journal (London: Aerospace Publishing) 33 (Summer 1998): 56–103. ISBN 1-86184-015-2. ISSN 0959-7050.

Further reading

- Gordon, Yefim; Rigmant, Vladimir (1998). Tupolev Tu-22 'Blinder' Tu-22M 'Backfire': Russia's long ranger supersonic bombers. Leicester: Midland Pub.. ISBN 1-85780-065-6.

|