Engineering:Waterloo and Whitehall Railway

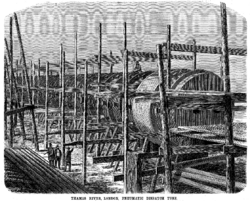

Illustration of the iron tube intended for use on the railway. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Dates of operation | 1865–1867 |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | Unknown |

The Waterloo and Whitehall Railway was a proposed and partly constructed 19th century Rammell pneumatic railway in central London intended to run under the River Thames just upstream from Hungerford Bridge, running from Waterloo station to the Whitehall end of Great Scotland Yard. The later Baker Street and Waterloo Railway followed a similar alignment for part of its route.

Origins

Authorised by the Waterloo and Whitehall Railway Act 1865, its route was:

A Railway commencing in the Parish of St Martin's-in-the-Fields in the County of Middlesex in the Street or Place known as Great Scotland Yard at or near the Western End thereof, and terminating in the Parish of Lambeth and County of Surrey in a Piece of Land belonging to the London and South-western Railway Company, and in the Occupation of Edwin Benjamin Gammon, near to and opposite the Arches under the Waterloo Station of that Railway numbered respectively 249 and 250.

The period was extended by the Waterloo and Whitehall Railway (Amendment) Act 1867 and Waterloo and Whitehall Railway Act 1868.

Technical information

The pneumatic pressure was to have been 22 lb/sq ft (1,100 Pa; 0.010 atm) in a 12-foot (3.7 m) diameter tube, with the engine at the Waterloo end sucking and then blowing 25 seat carriages acting as pistons.[1] Edmund Wragge was resident engineer.

The railway was intended to cross the river in a tunnel formed of four prefabricated sections of tube, each 220 feet (67 m) long, laid in a trench dredged across the river. The sections were to be joined by introducing their ends into junction chambers formed in brick piers constructed below the level of the existing riverbed. The piers were also designed to bear the weight of the sections, which were made of three-quarter-inch boiler plate, surrounded by four rings of brick work, firmly held in place by cement and flanged rings riveted onto the metal. Each section (of which at least one was completed) weighed almost 1,000 tons. Prefabrication began at the Samuda Brothers shipyard, at Poplar, five miles downstream.[2] If completed, it would have been the first Tube railway.[3]

Decline and abandonment

The line was hit by the 1866 financial crisis caused by the Overend, Gurney and Company bank collapse. On 2 September 1870 the Board of Trade used the Abandonment of Railways Act 1850 and the Railway Companies Act 1867 to declare the railway should be abandoned by the company.[4]

Further developments

A further railway, the Charing Cross and Waterloo Electric Railway, was incorporated by an Act of 1882 but was abandoned by an Act of 16 July 1885. A third company, the Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, secured an Act in 1893. This project was also put on hold, but eventually became the Bakerloo line.[5]

Remains

Parts of the works remained and at some stages there were tubes at the bottom of the Thames[6] and piles protruding from the river.[7] The trench excavated at the northern end is said now to be the wine cellar of the National Liberal Club.[3][8] Some works appeared during construction of the Shell Centre on the South Bank.

References

[ ⚑ ] 51°30′21.75″N 0°7′35.88″W / 51.5060417°N 0.1266333°W

|

- ↑ Klapper, Charles Frederick (1976). London's lost railways. p. 49.

- ↑ "Railway Engineering in London". Scientific American 15 (23): 368. 1866. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican12011866-368. https://books.google.com/books?id=kjdJAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA368.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bextor, Robin (2013). Little Book of the London Underground. Woking: Demand Media Limited. ISBN 9781909217379.

- ↑ "Abortive Railway Projects". Law Commission. 2009. pp. 343–5. http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/docs/abortive_railway_projects.pdf.

- ↑ TfL Bakerloo line facts: History

- ↑ Nokes, George Augustus (1895). The History of the South-Eastern Railway. Railway Press. p. 27. https://archive.org/details/historysoutheas00nokegoog.

- ↑ Hansard HC Deb 16 April 1869 vol 195 c972

- ↑ "CULG - Bakerloo Line". http://www.davros.org/rail/culg/bakerloo.html.