Engineering:Honda CB750 and CR750

1969 Honda CB750 | |

| Manufacturer | Honda |

|---|---|

| Also called | Honda Dream CB750 Four[1] |

| Production | 1969–2008 |

| Assembly | Wakō, Saitama, Japan Hamamatsu, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan Suzuka, Mie, Japan[2] |

| Predecessor | Honda CB450 |

| Successor | Honda CBX750 |

| Class | Sport bike or standard |

| Engine | 736 cc (44.9 cu in) SOHC air-cooled straight four (1969–1978)[1] DOHC air-cooled straight 4 (1979–2003, 2007) |

| Bore / stroke | 61 mm × 63 mm (2.4 in × 2.5 in)[1] |

| Top speed | 125 mph (201 km/h) |

| Power | 51 kW (68 hp) @ 8500 rpm (1969)[3] 50 kW (67 hp) @ 8000 rpm (DIN)[1][4] |

| Torque | 44 lbf⋅ft (60 N⋅m) @ 7000 rpm |

| Transmission | 5-speed manual, chain final drive |

| Suspension | Front: telescopic forks Rear: swingarm with two spring/shock units. |

| Brakes | Front disc / Rear drum |

| Tires | Front: 3.25" x 19" Rear: 4.00" x 18" |

| Rake, trail | 94 mm (3.7 in) |

| Wheelbase | 1,460 mm (57.3 in) |

| Dimensions | L: 2,200 mm (85 in) W: 890 mm (35 in) H: 1,100 mm (44 in) |

| Seat height | 790 mm (31 in) |

| Weight | 218 kg (481 lb)[1] (dry) 233 kg (513 lb)[5] (wet) |

| Fuel capacity | 19 L (4.2 imp gal; 5.0 US gal)[1] |

| Fuel consumption | 34.3 mpg‑US (6.86 L/100 km; 41.2 mpg‑imp)[6] |

The Honda CB750 is an air-cooled, transverse, in-line-four-cylinder-engine motorcycle made by Honda over several generations for year models 1969–2008 with an upright, or standard, riding posture. It is often called the original Universal Japanese Motorcycle (UJM) and also is regarded as the first motorcycle to be called a "superbike".[6][7][4][8]

The CR750 is the associated works racer.

Though other manufacturers had marketed the transverse, overhead camshaft, inline four-cylinder engine configuration and the layout had been used in racing engines prior to World War II, Honda popularized the configuration with the CB750, and the layout subsequently became the dominant sport bike engine layout.

The CB750 is included in the AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame Classic Bikes;[9][10] was named in the Discovery Channel's "Greatest Motorbikes Ever";[11] was in The Art of the Motorcycle exhibition,[7] and is in the UK National Motor Museum.[12] The Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, Inc. rates the 1969 CB750 as one of the 240 Landmarks of Japanese Automotive Technology.[1]

Although the CB750 nameplate has carried on throughout multiple generations, the original CB750 line from 1969-1983 was succeeded by the CBX750, which used the CB750 designation for several of its derivatives.

History

Honda of Japan introduced the CB750 motorcycle to the US and European markets in 1969 after experiencing success with its smaller motorcycles. In the late 1960s Honda motorcycles were, overall, the world's biggest sellers. There were the C100 Cub step-through—the best-selling motorcycle of all time—the C71, C72, C77 and CA77/8 Dreams; and the CB72/77 Super Hawks/Sports. A taste of what was ahead came with the introduction of the revolutionary CB450 DOHC twin-cylinder machine in 1966. Profits from these production bikes financed the successful racing machines of the 1960s, and lessons learned from racing were applied to the CB750. The CB750 was targeted directly at the US market after Honda officials, including founder Soichiro Honda, repeatedly met US dealers and understood the opportunity for a larger bike.

Early racing

In 1967 American Honda's service manager Bob Hansen[13][14] flew to Japan and discussed with Soichiro Honda the possibility of using Grand Prix technology in bikes prepared for American motorcycle events. American racing's governing body, the AMA, had rules that allowed racing by production machines only, and restricted overhead-valve engines to 500 cc whilst allowing the side-valve Harley Davidsons to compete with 750 cc engines.[15] Honda knew that what won on the race track today, sold in the show rooms tomorrow, and a large engine capacity road machine would have to be built to compete with the Harley Davidson and Triumph twin-cylinder machines.

Hansen told Soichiro Honda that he should build a 'King of Motorcycles',[failed verification] and the CB750 appeared at the Tokyo Show in November 1968. In the UK, it was publicly launched at the Brighton motorcycle show, held at the Metropole Hotel exhibition centre during April 1969,[16][17] with an earlier press-launch at Honda's London headquarters;[16][17] the pre-production versions appeared with a high and very wide handlebar intended for the US market.[16]

The AMA Competition Committee recognised the need for more variation of racing motorcycle and changed the rules from 1970, by standardizing a full 750 cc displacement for all engines regardless of valve location or number of cylinders, enabling Triumph and BSA to field their 750 cc triples instead of the 500 cc Triumph Daytona twins.[15]

The Honda factory responded by producing four works-racer CR750s, a racing version of the production CB750, ridden by UK-based Ralph Bryans, Tommy Robb and Bill Smith under the supervision of Mr Nakamura, and a fourth machine under Hansen ridden by Dick Mann. The three Japanese-prepared machines all failed during the race with Mann just holding on to win by a few seconds with a failing engine.[15]

Hansen's race team's historic victory at the March 1970 Daytona 200 with Dick Mann riding a tall-geared CR750 to victory[2][18] preceded the June 1970 Isle of Man TT races when two 'official' Honda CB750s were entered, again ridden by Irishman Tommy Robb partnered in the team by experienced English racer John Cooper. The machines were entered into the 750 cc Production Class, a category for road-based machines allowing a limited number of strictly-controlled modifications. They finished in eighth and ninth places.[19] Cooper was interviewed in UK monthly magazine Motorcycle Mechanics, stating both riders were unhappy with their poor-handling Hondas, and that he would not ride in the next year's race "unless the bikes have been greatly improved".[20]

In 1973, Japanese rider Morio Sumiya finished in sixth place in the Daytona 200-Mile race on a factory 750.[21]

Production and reception

Under development for a year,[22] the CB750 had a transverse straight-four engine with a single overhead camshaft (SOHC) and a front disc brake, neither of which had previously been available on an affordable mainstream production motorcycle. This spec, married with the introductory price of US$1,495[23] (US$10,423 in current money), gave the CB750 a considerable sporting-performance advantage over its competition, particularly its British rivals.

Cycle magazine called the CB750, "the most sophisticated production bike ever" at the time of the bike's introduction.[23] Cycle World called it a masterpiece, highlighting Honda's painstaking durability testing, the bike's 124 mph (200 km/h) top speed, the fade-free braking, the comfortable ride, and the excellent instrumentation.[22]

The CB750 was the first modern four-cylinder machine from a mainstream manufacturer,[24] and the term superbike was coined to describe it.[4][10] Adding to the bike's value were its electric starter, kill switch, dual mirrors, flashing turn signals, easily maintained valves, and overall smoothness and low vibration both under way and at a standstill. Much later models from 1991 included maintenance-free hydraulic valves.

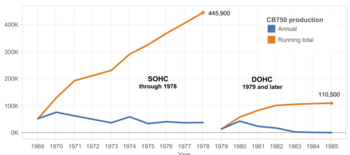

Unsure of the bike's reception and therefore unable to accurately gauge demand for the new bike, Honda limited its initial investment in the production dies for the CB750's engine by using a technique called permanent mould casting (often erroneously referred to as sandcasting), rather than diecasting.[25] The bike remained in the Honda line up for ten years, with a production total over 400,000.[26]

Models

Note: All CB750 engines are air/oil-cooled, as opposed to liquid-cooled

SOHC

Year and model code:[27]

- 1969 CB750 (6 June), CB750K or CB750K0 (date unknown)

- 1970 CB750K1 (21 September)

- 1972 CB750K2 (US 1 March)

- 1973 CB750K3 (US-only 1 February. K2 elsewhere)

- 1974 CB750K4 (US/Japan-only, K2 elsewhere)

- 1975 CB750K5 (US-only, K2/K4 elsewhere), CB750FO, CB750A (Canada-only)[28] The 1975 CB750F had a more streamlined look, thanks in part to a 4-into-1 exhaust and cafe style seat with fiberglass rear. Other changes included the use of a rear disc brake and a lighter crankshaft and flywheel.

- 1976 CB750K6, CB750F1, CB750A

- 1977 CB750K7, CB750F2, CB750A1

- 1978 CB750K8 (US-only), CB750F3, CB750A2

| Model | Production (rounded figures)[29] |

|---|---|

| CB750K0 | 53,400 |

| CB750K1 | 77,000 |

| CB750K2 | 63,500 |

| CB750K3 | 38,000 |

| CB750K4 | 60,000 |

| CB750K5 | 35,000 |

| CB750K6 | 42,000 |

| CB750K7 | 38,000 |

| CB750K8 | 39,000 |

| CB750F | 15,000 |

| CB750F1 | 44,000 |

| CB750F2 | 25,000 |

| CB750F3 | 18,400 |

| CB750A | 4,100 |

| CB750A1 | 2,300 |

| CB750A2 | 1,700 |

DOHC

- 1979–1982 CB750K

- 1979 CB750K 10th Anniversary Edition (5,000 produced for US)

- 1979–1982 CB750F

- 1980–1983 CB750C "Custom"

- 1982–1983 CB750SC Nighthawk

- 1984–1986 CB750SC Nighthawk S (Horizon in Japan. Export version of the CBX750.)

- 1991–2003 Nighthawk 750

- 1992–2008 CB750 (sold as CB750F2 and CB Seven-Fifty in Europe)

- 2023-Present CB750 Hornet (Derived from the 2023 Transalp)

CB750A Hondamatic

| Also called | Hondamatic |

|---|---|

| Production | 1976–1978[30] |

| Engine | 736.6 cc (44.95 cu in) inline-four, SOHC air-cooled |

| Bore / stroke | 61.0 mm × 63.0 mm (2.40 in × 2.48 in) |

| Compression ratio | 7.7:1 |

| Top speed | 156 km/h (97 mph)[31] |

| Power | 35 kW (47 hp) @ 7500 rpm[30] |

| Torque | 5.0 kg⋅m (49 N⋅m; 36 lbf⋅ft) @ 6000 rpm[30] |

| Ignition type | Coil |

| Transmission | 2-speed automatic, w/torque converter, chain |

| Brakes | Front: 296 mm (11.7 in) disc Rear: 180 mm (7.1 in) drum |

| Tires | Front: 3.5" x 19" Rear: 4.5" x 17" |

| Rake, trail | 28°, 110 mm (4.5 in) |

| Wheelbase | 1,470 mm (58.0 in) |

| Dimensions | L: 2,260 mm (89.0 in) W: 800 mm (31.5 in) |

| Seat height | 840 mm (33.0 in) |

| Weight | 262 kg (578 lb) (claimed)[32] (dry) 259 kg (572 lb)[31] (wet) |

| Fuel capacity | 18 L (4.0 imp gal; 4.8 US gal) |

In 1976, Honda introduced the CB750A to the United States, with the A suffix designating "Automatic", for its automatic transmission. Although the two-speed transmission includes a torque converter typical of an automatic transmission, the transmission does not automatically change gears for the rider. Each gear is selected by a foot-controlled hydraulic valve/selector (similar in operation to a manual transmission motorcycle).[30][33] The foot selector controls the application of high pressure oil to a single clutch pack (one clutch for each gear), causing the selected clutch (and gear) to engage. The selected gear remains selected until changed by the rider, or the kickstand is lowered (which shifts the transmission to neutral).[31]

The CB750A was sold in the North American and Japanese markets only.[33] The name Hondamatic was shared with Honda cars of the 1970s, but the motorcycle transmission was not fully automatic. The design of the transmission is similar in concept to the transmission in Honda's N360AT,[31][34] a kei car sold in Japan from 1967 to 1972.

The CB750A uses the same engine as the CB750, but detuned with lower 7.7:1 compression and smaller carburettors producing a lower output, 35.0 kW (47.0 hp). The same oil is used for the engine and transmission, and the engine was changed to a wet sump instead of dry sump type. A lockout safety device prevents the transmission from moving out of neutral if the side stand is down. There is no tachometer but the instruments include a fuel gauge and gear indicator. For 1977 the gearing was revised, and the exhaust changed to a four-into-two with a silencer on either side. Due to slow sales the model was discontinued in 1978,[30] though Honda did later introduce smaller Hondamatic motorcycles (namely the CB400A, CM400A,[35] and CM450A).[36] Cycle World tested the 1976 CB750A's top speed at 156 km/h (97 mph), with a 0 to 60 mph (0 to 97 km/h) time of 10.0 seconds and a standing 1⁄4 mile (0.40 km) time of 15.90 seconds at 138.95 km/h (86.34 mph).[31] Braking from 60 to 0 mph (97 to 0 km/h) was 39 m (129 ft).[31]

Nighthawk 750 & CBX750 derived CB750 Models

From 1982 through 2003, with the exception of several years, Honda produced a CB750 known as the Nighthawk 750. As the motorcycle market in the early 1980s began to experience segmentation and the prevalence of UJMs began to dwindle, Honda made efforts to hold its territory on the market by offering more specific variants of their existing bikes as the company was still in the midst of researching and developing dedicated sportbike and cruiser lines.[37] The cruiser variant of many of the Honda models offered at the time would be known as "customs"; this included but was not limited to the CB900C, CX500C, CM250C and the CB750C, and these bikes would prove to be the most popular with American consumers. Therefore, expanding upon the niche that the CB750C "Custom" had initiated along with its' "custom" stable mates, a new series of bikes appeared with the surname "Nighthawk". These bikes would continue to take on the 'pseudo' cruiser bike aesthetic that was specifically catered for the North American market at the time along with offering certain upmarket features, one notable feature being hydraulic valves. Along with the normal CB750 1982-1983 variants the CB750SC Nighthawk would be offered.[38][39] The Nighthawk 750SC had a 749cc 4-stroke engine with a 5-speed manual transmission, chain drive, front disc and rear drum brakes. Also exclusive to the Nighthawk variant was Honda's TRAC (Torque Reactive Anti-Dive System).[40] Because of the 1983 motorcycle tariff, the Nighthawk CB750SC was soon replaced by the smaller, yet more sporty and sophisticated CB700SC Nighthawk S. This new motorcycle was a downsized version of the CB750SC Nighthawk S, the export variant of the CB750's successor, the CBX750[41]

After the discontinuation of the CB700SC Nighthawk S in 1986 and the tariff being lifted in 1987 Honda decided not to follow up with the larger CB750SC Nighthawk S, which was offered for the Canadian market. Instead, as was typically the case for many Japanese corporations during the bubble years, Honda began to experiment with its standard bike offerings by first by releasing the V-twin NT650 in 1988 and later both the boutique-developed cafe racer GB500 and CBR400RR derived CB-1 in 1989. Though innovative in their own right, these motorcycles had very short lives in the North American Market and soon Honda customers demanded a return to the traditional UJM style that had fallen out of prominence due to market segmentation. Also in 1989, Kawasaki had successfully released the Zephyr 400 in the Japanese market and soon 550cc and 750cc versions would debut for export markets as well, which was an indicator that a return to form was needed in order to meet demand both at home and abroad.

Honda responded in the summer of 1991 with the RC38 Nighthawk 750, which was marketed in both North America and Japan, though for the latter only for a single year as the RC39 CB750 Nighthawk.[42] The following year, the higher spec RC42 CB750 would debut for Europe and Japanese markets (in Europe it went by either CB750F2 or CB Seven-Fifty). Both of these sister bikes were parts-bin specials, mainly being mechanical descendants of the CBX750 yet also borrowing numerous components from other bikes such as the CBR600F2, Goldwing and CB-1.[43][44] The RC38 Nighthawk 750 differed from the RC42 CB750 by taking on a more basic, budget-friendly approach with its packaging; instead of the CB750's dual front disc and single rear disc brake setup, the Nighthawk 750 instead made use with a single disc brake in the front and a rear drum brake. The fork rake angle on the Nighthawk 750 was slightly increased and conventional twin hydraulic shock absorbers were used instead of the CB750's gas-charged absorbers; the Nighthawk's foot rest were welded to the frame, rather than being interchangeable like on the CB750 and the styling for the Nighthawk was given a more 'retro', smoother reworking that was reminiscent of the 1982-1983 CB750SC. The engine, exhaust, transmission, gearing and gauges were the same on both bikes.

The entry-level 1992-2008 Nighthawk 250 was derived from the Nighthawk 750.

2007 CB750 Special Edition

In 2007 Honda Japan announced the CB750 Special Edition. This limited edition run was put forth to commemorate the 25th anniversary of "Fast Freddie" Spencer joining the Honda Grand Prix Team and a version of this bike donning the "Digital Silver Metallic" color of the CB750 racebike Spencer used in the 1981 AMA Superbike championship was offered alongside a version that was painted in "Candy Blazing Red" reminiscent of the CBX1000.[45]

Discontinuation and Successors

The CB750F2/CB Seven-Fifty was discontinued for the European market in 2001 and in 2003 the Nighthawk 750 was discontinued in North America, though the CB750 would continue in Japan until 2008 when 2007 automobile exhaust gas regulations went into effect. This would lead the CBR-based Honda Hornet CB600F to eventually take over the role as Honda's middleweight standard bike offering in both Europe and North America; concurrent with other Japanese manufacturers at the time shifting away from traditional, utilitarian standard motorcycles and transitioning towards supersport derived naked bikes in those markets.

In 2010, Honda released the CB1100, which although well over 750cc in displacement and fuel-injected was marketed as a spiritual successor to the CB750, both in style and in concept; this motorcycle would be later sold to Europe and North America from 2013 until 2022.

2023 CB750 Hornet

In 2023, Honda Motor Europe Ltd revived the CB750 nameplate once more in the form of the CB750 Hornet. This new model, though sharing the same name, takes a major departure from the established layout that previous CB750s possessed, namely in regards to its engine configuration and fuel injection system. The frame and engine of the motorcycle is lifted directly from new XL750 Transalp; the new engine being a 755cc DOHC 8-valve liquid-cooled parallel twin with a output of 90.5 hp @ 9,500 rpm and 55.3 lb.-ft. @ 7,250 rpm. [46] It is also the first CB750 to use Honda's PGM-FI fuel system. The CB750 Hornet is currently only sold for the European market.

Specifications

| Model | Engine displacement | Fuel system | Cam | Valves per cylinder | Power | Torque | Weight | Drive |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1969–1978 CB750 Four[47][48] | 736 cc (44.9 cu in)[48] | 4 carburettors[48] | SOHC[48] | 2 | 67 bhp (50 kW) @ 8000 rpm[7][48][49] | 59.8 N⋅m (44.1 lbf⋅ft) @ 7000 rpm[48] | 218 kg (481 lb) (dry)[48] | 5-Speed, Constant Mesh, Gearbox, Final Drive Chain[48] |

| 1976–1978 CB750A[32] | 736 cc (44.9 cu in) | 4 carburettors | SOHC | 2 | 35 kW (47 hp) @ 7500 rpm[30] | 262 kg (578 lb) (claimed dry)[32] 259 kg (572 lb) (wet) [31] |

2-speed w/torque converter, chain[30] | |

| 1978 CB750K[50] | 748 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 carburettors | DOHC | 4 | 50 kW (67 hp) @ 9000 rpm | 5-Speed, Constant Mesh, Gearbox, Final Drive Chain | ||

| 1979–1980 CB750F (RC04)[51] | 748 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 carburettors[51] | DOHC[51] | 4 | 50 kW (67 hp) @ 9000 rpm[51] | 42.6 lb⋅ft (57.8 N⋅m) @ 8000 rpm[51] | 228 kg (503 lb) Dry[51] | 5-Speed, Constant Mesh, Gearbox, Final Drive Chain[51] |

| 1980–1982 CB750C Custom[52] | 748 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 carburettors[52] | DOHC[52] | 4 | 50 kW (67 hp) @ 9000 rpm[52] | 42.6 lb⋅ft (57.8 N⋅m) @ 8000 rpm[52] | 236 kg (520 lb) dry [52] ~252 kg (556 lb) wet[52] |

5-Speed, Constant Mesh, Gearbox, Final Drive Chain[52] |

| 1981 CB750F | 748 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 carburettors | DOHC | 4 | 42.6 lb⋅ft (57.8 N⋅m) @ 8000 rpm | Chain | ||

| 1982–1983 CB750SC (Nighthawk) | 749 cc (45.7 cu in) | 4 carburettors | DOHC | 4 | ||||

| 1991-2003

(Nighthawk 750) |

747 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 Keihin 34 mm Constant Vacuum carburettors | DOHC | 4 | Chain | |||

| 1992-2008 CB750 (1992-2001 CB750F2) | 747 cc (45.6 cu in) | 4 Keihin 34 mm Constant Vacuum carburetors (1992-2003)

Keihin VENA Carbs (2004-2008) |

DOHC | 4 | 55 kW (74 hp) @ 8500 rpm[53] | 64 N⋅m (47 lbf⋅ft) @ 7500 rpm[53] | 240 kg (520 lb)[53] | Chain |

| 2023-CB750 Hornet | 755cc

(46 cu in) |

PGM-FI | DOHC | 4 | 67.5 kW (90 hp) @

9500 rpm[54] |

75 Nm (55.3 lb-ft) @

7250 rpm |

190kg (419 lb)

(wet) |

Chain |

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Honda Dream CB750". 240 Landmarks of Japanese Automotive Technology. Society of Automotive Engineers of Japan, Inc.. http://www.jsae.or.jp/autotech/data_e/4-16e.html. "Developed with the goal of giving riders greater power with better safety, the Dream CB750 featured Honda's first double cradle frame and the world's first hydraulic front disc brakes."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Honda. "The Dream CB750 Four (Official history)". http://world.honda.com/history/challenge/1969cb750four/index.html.

- ↑ Honda CB750 – It Really Changed Everything, by Paul Crowe – "The Kneeslider" on 5 January 2008.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Walker, Mick (2006), Motorcycle: Evolution, Design, Passion, JHU Press, p. 150, ISBN 0-8018-8530-2, https://books.google.com/books?id=AHSlknpjrgAC&pg=PA150

- ↑ "Cycle World Road Test: Honda CB750", Cycle World 8 (8): 44–51, August 1970

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Landon Hall (July–August 2006). "Honda CB750 Four: A Classic for the Masses". Motorcycle Classics. http://www.motorcycleclassics.com/motorcycle-reviews/2006-07-01/classic-for-the-masses-honda-cb750.aspx.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Statnekov, Daniel K.; Guggenheim Museum Staff (1998), "Honda CB750 Four", in Krens, Thomas; Drutt, Matthew, The Art of the Motorcycle, Harry N. Abrams, p. 312, ISBN 0-8109-6912-2

- ↑ Frank, Aaron (2003), Honda Motorcycles, MotorBooks/MBI Publishing Company, p. 92, ISBN 0-7603-1077-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=CSxTaoGagKoC&pg=PA92, retrieved 20 February 2010

- ↑ Motorcycle Hall of Fame, 1969 Honda CB750; The Year of the Super-bike, American Motorcyclist Association, http://www.motorcyclemuseum.org/classics/bike.asp?id=91

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "The Dawn of the Superbike: Honda's Remarkable CB750", AMA Motorcycle Hall of Fame (American Motorcyclist Association), http://www.motorcyclemuseum.org/exhibits/superbikes/CB750/CB750.asp, retrieved 20 February 2010

- ↑ "Greatest Motorbikes Ever". Discovery Channel. http://www.discoverychannel.co.uk/greatest_ever/motorbikes/index.shtml.

- ↑ List of vehicles, National Motor Museum Trust, http://www.nationalmotormuseum.org.uk/?location_id=335, retrieved 19 October 2010

- ↑ Girdler, Alan. Bob Hansen, 1919–2013 A long and rewarding life. Cycle World

- ↑ Template:Mhof

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Mann and machine, Motorcyclist online Retrieved 13 June 2015

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Motorcycle Sport, UK monthly magazine, April 1969, pp. Cover, 121, 132–133. Honda's 750-4 arrives. "The wide, sweeping handlebars on the machines shown at Brighton are fitted in the US market, but before deciding on whether or not these will be the ones for this country some discussion will take place between Honda UK and dealers and prospective owners". Accessed 15 June 2015

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Motorcycle Mechanics, May 1969, Showtime – 6-page-special. pp. Cover, 38–39, Honda's Four. "MM takes a close look at the new 4-pot Honda 750". Accessed 15 June 2015

- ↑ Original Honda CB750 by John Wyatt – Bay View Books Ltd 1998

- ↑ Isle of Man TT Races official site 1970 Production 750cc Results Retrieved 13 June 2015

- ↑ Motorcycle Mechanics, December 1970, pp.36–37 John Cooper interview by Charles Deane (editor). Accessed 13 June 2015

- ↑ Honda WorldWide, Honda Motor Co., Ltd official site Retrieved 20 June 2015

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 "Honda's Fabulous 750 Four; Honda Launches the Ultimate Weapon in One-Upmanship — a Magnificent, Musclebound, Racer for the Road", Cycle World: 36–39, January 1969, ISSN 0011-4286

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "Cycle Road Test: Honda 750cc Four", Cycle: 33–39, 78–81, August 1969

- ↑ Wilson, H. (1995), The Encyclopedia of the Motorcycle, Dorling Kindersley Limited, pp. 88–89, ISBN 0-7513-0206-6

- ↑ Employing an Idle Facility to Produce a Large Motorcycle, http://world.honda.com/history/challenge/1969cb750four/page04.html, retrieved 25 August 2014

- ↑ Alexander, Jeffrey W. (2009), Japan's Motorcycle Wars: An Industry History, UBC Press, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-7748-1454-6, https://books.google.com/books?id=Q473NKddjnAC&pg=PA206, retrieved 5 April 2011

- ↑ Mick Duckworth (June 2004), "Classic Bike Dossier: Honda CB750", Classic Bike, http://www.classicbike.co.uk/pdf/506/197883.pdf, retrieved 15 January 2008[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Richard Backus (May–June 2010). "Honda CB750F Super Sport". Motorcycle Classics. http://www.motorcycleclassics.com/motorcycle-reviews/honda-cb750f-super-sport.aspx.

- ↑ Classic Bike Glamorous and Glorious by Mick Duckworth June 2004 issue

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 30.5 30.6 Bacon, Roy (1996), Honda: The Early Classic Motorcycles : All the Singles, Twins and Fours, Including Production Racers and Gold Wing-1947 to 1977, Niton Publishing, pp. 110, 112, 185, 192, ISBN 1-85579-028-9

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 31.6 "Honda's CB750F Stick versus the CB750A Automatic", Cycle World (Newport Beach, California: Hachette Filipacchi Media U.S.) 15 (9): 60–65, September 1976, ISSN 0011-4286

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Honda Press 1977, Honda EARA.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ker, Rod (2007), Classic Japanese Motorcycle Guide, Sparkford, UK: Haynes Publishing, p. 81, ISBN 978-1-84425-335-7

- ↑ The Hondamatic Transmission, The Innovative Automatic Transmission: A Breakthrough in Original Thinking, 1968

- ↑ Honda Shop Manual CB/CM400's. Honda Motor Co. Ltd. December 1980. p. 1.

- ↑ Honda Shop Manual CB/CM450's. American Honda Motor Co.. 1984. p. 4.

- ↑ "Requiem for a Cruiser : A Brief History of Honda Cruisers" (in en-US). https://cdnbkr.ca/vintage-motorcycles/history-honda-cruisers/.

- ↑ Andy Saunders. "Frugal Flyers: A Six-Bike Shoot Out". motorcycle.com. http://www.motorcycle.com/shoot-outs/frugal-flyers-a-sixbike-shoot-out-576.html.

- ↑ MO Staff. "2000 Valuebike Shootout". motorcycle.com. http://www.motorcycle.com/shoot-outs/2000-valuebike-shootout-15645.html.

- ↑ "Honda CB 750SC Nighthawk". https://www.motorcyclespecs.co.za/model/Honda/honda_cb750sc_82.htm.

- ↑ "Shawn T. Samuelson's Honda Nighthawk page". https://stsamuel.tripod.com/nighthawk.html.

- ↑ "ホンダ・ナイトホーク" (in ja), Wikipedia, 2021-03-15, https://ja.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E3%83%9B%E3%83%B3%E3%83%80%E3%83%BB%E3%83%8A%E3%82%A4%E3%83%88%E3%83%9B%E3%83%BC%E3%82%AF&oldid=82419031, retrieved 2024-01-04

- ↑ "ホンダ CB750(1992年モデル)の基本情報 | ヒストリー | 中古バイク情報はBBB". https://www.bbb-bike.com/history/data132_1.html.

- ↑ "ホンダ・CB750" (in ja), Wikipedia, 2022-08-22, https://ja.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=%E3%83%9B%E3%83%B3%E3%83%80%E3%83%BBCB750&oldid=91104825, retrieved 2024-01-04

- ↑ "Honda Japan website". http://www.honda.co.jp/motor-lineup/cb750/photo/index.html.

- ↑ "2023 Honda CB750 Hornet First Look" (in en). https://www.cycleworld.com/story/bikes/honda-cb750-hornet-first-look-2023/.

- ↑ Honda Press 18 July 1969, Honda Dream 18 July 1969 CB750 FOUR.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 48.6 48.7 Honda Dream CB750 Four History, The First Motorcycle to Offer Disc Brakes.

- ↑ Brown, Roland (2005), The ultimate history of fast motorcycles, Bath, England: Parragon, pp. 114–115, ISBN 1-4054-5466-0

- ↑ Honda Press Dec 1978, 1978 Honda CB750K.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 51.5 51.6 Honda Press June 1979, 1979 Honda CB750F Released 23 June 1979.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 52.6 52.7 Honda Press May 20, 1980, 1980 Honda CB750C, CB750K, CB750F Press Release.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 "Honda CB750 Specifications" (in ja). Honda Japan. http://www.honda.co.jp/motor-lineup/cb750/spec/?from=rcount.

- ↑ "2023 Honda CB 750 Hornet". https://www.motorcyclespecs.co.za/model/Honda/honda-cb750-hornet-23.html.

External links

- CB750 images at the 1969 Brighton Motorcycle Show

- Boehm, Mitch (29 July 2014), "The Honda CB750 Sandcast Prototype; In early 1969, Honda's guys hand-built four CB prototypes. Three are gone. This is the story of the fourth", Motorcyclist, https://www.motorcyclistonline.com/news/honda-cb750-sandcast-prototype

pt:Honda CB 750 Four

|