Engineering:Z1 (computer)

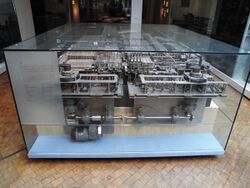

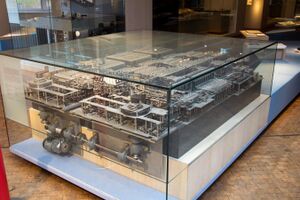

Replica of the Z1 in the German Museum of Technology in Berlin | |

| Also known as | V1 (Versuchsmodell 1) |

|---|---|

| Developer | Konrad Zuse |

| Type | Programmable, binary, electrically motor-driven mechanical computer |

| Release date | 1938 |

| Lifespan | 5 years |

| Media | 35-millimeter film |

| CPU | Ca. 30,000 metal sheets @ 1 Hz |

| Memory | 16-word floating point memory |

| Input | Keyboard, punched tape reader |

| Power | Electrical engine of a vacuum cleaner |

| Mass | 1 tonne (2,200 lb) |

| Successor | Z2 |

The Z1 was a motor-driven mechanical computer designed by Konrad Zuse from 1936 to 1937, which he built in his parents' home from 1936 to 1938.[1][2] It was a binary electrically driven mechanical calculator with limited programmability, reading instructions from punched celluloid film.

The “Z1” was the first freely programmable computer in the world that used Boolean logic and binary floating-point numbers; however, it was unreliable in operation.[3][4] It was completed in 1938 and financed completely by private funds. This computer was destroyed in the bombardment of Berlin in December 1943, during World War II, together with all construction plans.

The Z1 was the first in a series of computers that Zuse designed. Its original name was "V1" for Versuchsmodell 1 (meaning Experimental Model 1). After WW2, it was renamed "Z1" to differentiate it from the flying bombs designed by Robert Lusser.[5] The Z2 and Z3 were follow-ups based on many of the same ideas as the Z1.

Design

The Z1 contained almost all the parts of a modern computer, i.e. control unit, memory, micro sequences, floating-point logic, and input-output devices. The Z1 was freely programmable via punched tape and a punched tape reader.[6] There was a clear separation between the punched tape reader, the control unit for supervising the whole machine and the execution of the instructions, the arithmetic unit, and the input and output devices. The input tape unit read perforations in 35-millimeter film.[7]

The Z1 was a 22-bit floating-point value adder and subtractor, with some control logic to make it capable of more complex operations such as multiplication (by repeated additions) and division (by repeated subtractions). The Z1's instruction set had eight instructions and it took between one and twenty-one cycles per instruction.

The Z1 had a 16-word floating point memory, where each word of memory could be read from – and written to – the control unit. The mechanical memory units were unique in their design and were patented by Konrad Zuse in 1936. The machine was only capable of executing instructions while reading from the punched tape reader, so the program itself was not loaded in its entirety into internal memory in advance.

The input and output were in decimal numbers, with a decimal exponent and the units had special machinery for converting these to and from binary numbers. The input and output instructions would be read or written as floating-point numbers. The program tape was a 35 mm film with the instructions encoded in punched holes.

Construction

"Z1 was a machine weighing about 1 tonne in weight, which consisted of some 20,000 parts. It was a programmable computer, based on binary floating-point numbers and a binary switching system. It consisted completely of thin metal sheets, which Zuse and his friends produced using a jigsaw."[8] "The [data] input device was a keyboard...The Z1's programs (Zuse called them Rechenpläne, computing plans) were stored on punch tapes using an 8-bit code"[8]

Construction of the Z1 was privately financed. Zuse got money from his parents, his sister Lieselotte, some students of the fraternity AV Motiv (cf. Helmut Schreyer), and Kurt Pannke (a calculating machine manufacturer in Berlin) to do so.

Zuse constructed the Z1 in his parents' apartment; in fact, he was allowed to use the living room for his construction. In 1936, Zuse quit his job in airplane construction to build the Z1.

Zuse is said to have used "thin metal strips" and perhaps "metal cylinders" or glass plates to construct Z1. There were probably no commercial relays in it (though the Z3 is said to have used a few telephone relays). The only electrical unit was an electric motor to give the clock frequency of 1 Hz (cycle per second) to the machine.

'The memory was constructed from thin strips of slotted metal and small pins and proved faster, smaller, and more reliable, than relays. The Z2 used the mechanical memory of the Z1 but used relay-based arithmetic. The Z3 was experimentally built entirely of relays. The Z4 was the first attempt at a commercial computer, reverting to the faster and more economical mechanical slotted metal strip memory, with relay processing, of the Z2, but the war interrupted the Z4 development.'[9]

The Z1 was never very reliable in operation because of poor synchronization caused by internal and external stresses on the mechanical parts.

While various sources make various statements about exactly how Zuse's computers were constructed, a clear understanding is gradually emerging.[10]

Reconstruction

The original Z1 was destroyed by the Allied air raids in 1943, but in the 1980s Zuse decided to rebuild the machine. The first sketches of the Z1 reconstruction were drawn in 1984. He constructed (with the help of two engineering students) thousands of elements of the Z1 again, and finished rebuilding the device in 1989. This replication has a 64-word memory instead of a 16-word one. The rebuilt Z1 (pictured) is displayed at the German Museum of Technology in Berlin.[7][11]

Quotation

There is a replica of this Model in the Museum of Traffic and Technology in Berlin. Back then it didn't function well, and in that regard the replica is very reliable — it also doesn't work well.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ (in en) Origins and Foundations of Computing: In Cooperation with Heinz Nixdorf MuseumsForum. Springer Science & Business Media. 2009-11-05. pp. 78–. ISBN 978-3-64202992-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=y4uTaLiN-wQC&q=%22arithmetic+unit%22+1938&pg=PA78. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ↑ (in en) The Plankalkül. Gesellschaft für Mathematik und Datenverarbeitung (GMD). 1976. pp. 21–. https://books.google.com/books?id=VN5UAAAAYAAJ&q=1938. Retrieved 2022-07-10.

- ↑ A Science of Operations: Machines, Logic and the Invention of Programming. Springer-Verlag. 2011. ISBN 978-1-84882-554-3.

- ↑ "The Zuse Computers". Resurrection - The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society (Computing Before Computers seminar, Science Museum: Computer Conservation Society (CCS)) 37. Spring 2006. ISSN 0958-7403. http://www.cs.man.ac.uk/CCS/res/res37.htm#c.

- ↑ "Obituary: Konrad Zuse". The Independent. 1995-12-21. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/obituary--konrad-zuse-1526795.html.

- ↑ "Konrad Zuse's Legacy: The Architecture of the Z1 and Z3". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 19 (2): 5–16. April–June 1997. doi:10.1109/85.586067. http://ed-thelen.org/comp-hist/Zuse_Z1_and_Z3.pdf. Retrieved 2022-07-03. (12 pages)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Reconstruction of the Z1 Computer". Free University of Berlin. https://dcmlr.inf.fu-berlin.de/rojas/reconstruction-of-the-z1-computer/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 "Konrad Zuse — the first relay computer". https://history-computer.com/ModernComputer/Relays/Zuse.html.

- ↑ "Who Made the First Computer". 2000. http://www.dai.ed.ac.uk/homes/cam/fcomp.shtml.

- ↑ "The Other First Computer: Konrad Zuse And The Z3: Zuse's Mechanical XNOR Gate". 2021-06-16. https://hackaday.com/2021/06/16/the-other-first-computer-konrad-zuse-and-the-z3/.

- ↑ The Z1: Architecture and Algorithms of Konrad Zuse's First Computer. 2014-06-07.

- ↑ Hellige, Hans Dieter, ed (2004) (in de). Geschichten der Informatik. Visionen, Paradigmen, Leitmotive. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag. p. 36. ISBN 978-3-540-00217-8.

Further reading

- (in en) The Computer – My Life. Springer Science & Business Media. 2013-03-09. p. 64. ISBN 978-3-66202931-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=edWoCAAAQBAJ&pg=PA64. (NB. This is a translation of the original German title Der Computer - Mein Lebenswerk.)

- The Design Principles of Konrad Zuse's Mechanical Computers. 2016-03-08. (NB. Paper describes the design principles of Zuse Z1.)

External links

- "The life and work of Konrad Zuse". EPEmag. http://www.epemag.com/zuse/.

- "Zuse Z1 detailed information". http://www.horst-zuse.homepage.t-online.de/Konrad_Zuse_index_english_html/rechner_z1.html.

- "An informative website about Zuse Z1". http://zuse-z1.zib.de.

- "A detailed walk-through of the Zuse Z1 major components". https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HDxs3-aJSAI.