Engineering:Horse engine

| This engineering may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Large and heavy header, text-focused images, and lengthy main section Please help improve this engineering if you can; the talk page may contain suggestions. |

A horse engine (also called a horse power or horse-power) is a (now largely obsolete) machine for using draft horses to power other machinery. It is a type of animal engine that was very common before internal combustion engines and electrification. A common design for the horse engine was a large treadmill on which one or more horses walked. The surface of the treadmill was made of wooden slats linked like a chain. Rotary motion from the treadmill was first passed to a planetary gear system, and then to a shaft or pulley that could be coupled to another machine. Such powers were called tread powers, railway powers, or endless-chain powers.[1]:1041[2][3]:277–282 Another common design was the horse wheel or sweep power, in which one or several horses walked in a circle, turning a shaft at the center.[1]:1041[2][3]:277–282 Mills driven by horse powers were called horse mills. Horse engines were often portable so that they could be attached to whichever implement they were needed for at the time. Others were built into horse-engine houses.

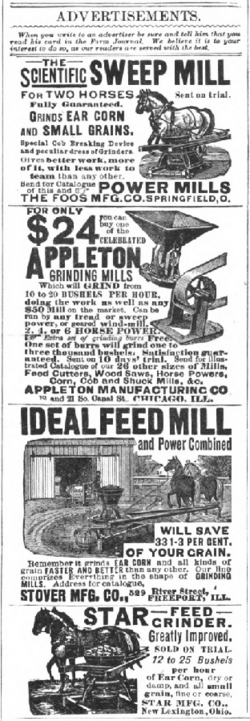

Examples of farm machinery powered with a horse engine include gristmills (see horse mill), threshing machines, corn shellers, feed cutters, silo blowers, grain grinders, pumps, and saws such as bucksaws and lumber mill saws. They could also be used interchangeably with other forms of power, such as a hand crank, stationary engine, portable engine, or the flat belt pulley or PTO shaft of a tractor, which eventually replaced them on most American and European farms.[citation needed]

Today there are still a few modern versions used by Amish people that assist in farm chores and that power machine shops via line shafts.[citation needed]

Designs, terms, and output

The term "horse power" probably predates the name of the horsepower unit of measurement. (For reference the 1864 Webster's Dictionary defines horse-power as “A machine operated by one or more horses; a horse engine.") The word "power" in late-19th-century American English, for example, was often used for any example in the whole category of power sources, including water powers, wind powers, horse powers (for example, sweep powers), dog powers, and even (in a few cases) sheep powers; in the Pennsylvania Oil Country during that era, sweep-style powers run by steam engines and gas engines to power oil derricks were called "powers" in the local vocabulary, just as horse powers on farms were also often simply called "powers",[3]:277–282 unless specification of the type was needed, in which case terms such as "tread power" or "sweep power" were used.[3]:277–282 Regional norms determined which term was more common in any given region or country.

The application or implement being run by the sweep power was often a feed mill or flour mill positioned right at the center, which meant that either no transmission at all was required (the hub of the wheel being also the output shaft) or at most a simple set of gears to step up the RPM for some applications. Transmitting the power output to an application or implement at a distance was accomplished through a shaft that today's typical terminology would call a drive shaft but that was usually called a tumble shaft at the time, at least in North America (sometimes tumbler shaft or tumbling rod). It was also sometimes called a jackshaft, as in many applications the tumble shaft and the countershaft (jackshaft) were one and the same rather than separate components.

Terminology was variable, as it was natural based on the logic of the instance. Words like "engine", "mill", "wheel", and "power" were all used as needed. Thus one article that talked about "jack wheels" was referring to the flat-belt pulleys on the tumble shaft that served as countershaft pulleys.

Wendel (2004)[3]:277–282 provides contemporary drawings from advertisements.

Power output was limited by the size of the team. Horse powers were often run with a single horse or a two-horse team, which means that, judged by today's standards, not much power output was available and the feed mill or pump being driven was a rather small one. Regarding choice of type, at various times and places there were accepted notions of conventional wisdom, such as that more usable power per horse came from a tread power than from a sweep power (in other words, that a sweep power was less efficient of the horse's effort) or that a tread power would wear down a horse prematurely (a notion roundly refuted by others).[2] Whether or not the efficiency notion was true, sweep powers were simpler and less expensive, so they remained popular. Some were 4-horse designs. Large sweep powers could make use of 6 to 12 horses, but not many family farms could muster that sort of arrangement. It is also true, however, that they had little need for it, as the entire material culture of the era had been shaped by the limited scale of power that manual labour and small teams of working animals could provide. But once convenient internal-combustion and electric power became widely available, though (via tractors, trucks, rural electrification, electric motors, small appliances, and so on), material culture evolved to take advantage of them. In comparing 19th-century material culture with today's, one can see that the ease of providing multiple horsepower to many different applications that we often take for granted today (such as 5 or 10 horsepower for each lawn mower, or 4 horsepower for a single wet-dry vacuum) would have seemed like a great blessing or luxury then.

Many horse-engine houses were built in Britain in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Relative to 1-horse and 2-horse powers, they could provide larger amounts of power through larger teams. Powering threshing machines was one of their main applications. They were not portable, but the farm culture of Britain was well suited to their stationary nature, as farming communities tended to be organized around villages. In North America, portable horse powers were more usual, with family farms spread far and wide. Even in cases where equipment was not owned by each farm—for example, owned jointly in co-ops or hired on a custom (job) basis—it tended to be portable, moving from farm to farm over country roads.

In the 19th century, even boats were powered by horse engines. Team boats were popular for river ferries.

Circa 1828, the Westminster Cracker Factory's machinery was powered by horse engine; steam power followed, and by 1922, the bakery was electrified.[4]

See also

- Horse mill

- Horse capstan

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Johnson, Cuthbert William (1844), The Farmer's Encyclopaedia, and Dictionary of Rural Affairs: Embracing All the Most Recent Discoveries in Agricultural Chemistry, 1, Carey and Hart, https://books.google.com/books?id=n4I5AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA1041.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Todd, S. Edwards (1850), "Railway or endless-chain horse power—threshing, sawing and cutting machines, &c., &c.", American Agriculturalist 9 (1): 156–157, https://books.google.com/books?id=PStKAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA156.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Wendel, Charles H. (2004), Encyclopedia of American Farm Implements and Antiques (2nd ed.), Iola, WI, USA: Krause Publications, ISBN 978-0873495684.

- ↑ (in en) The Cracker Baker. American Trade Publishing Company. 1922. pp. 38. https://books.google.com/books?id=SSRLAQAAMAAJ&dq=%22westminster+cracker%22&pg=RA10-PA38.

External links

- The Papers of John C. Calhoun[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}] - mention horse power machines

- Photograph of a horse power being used to thresh wheat in southeastern Washington State. From the Garfield County Heritage Collection.

|