Physics:Periscope

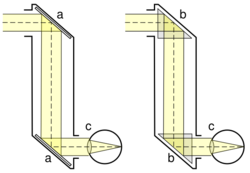

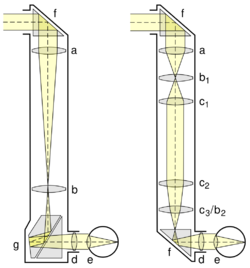

a Objective lens

b Field lens

c Image erecting lens

d Ocular lens

e Lens of the observer's eye

f Right-angled prism

g Image-erecting prism

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.[1][2]

In its simplest form, it consists of an outer case with mirrors at each end set parallel to each other at a 45° angle. This form of periscope, with the addition of two simple lenses, served for observation purposes in the trenches during World War I. Military personnel also use periscopes in some gun turrets and in armoured vehicles.[1]

More complex periscopes using prisms or advanced fiber optics instead of mirrors and providing magnification operate on submarines and in various fields of science. The overall design of the classical submarine periscope is very simple: two telescopes pointed into each other. If the two telescopes have different individual magnification, the difference between them causes an overall magnification or reduction.

Early examples

Johannes Hevelius described an early periscope (which he called a "polemoscope") with lenses in 1647 in his work Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio [Selenography, or an account of the Moon]. Hevelius saw military applications for his invention.

In 1854, Hippolyte Marié-Davy invented the first naval periscope, consisting of a vertical tube with two small mirrors fixed at each end at 45°. Simon Lake used periscopes in his submarines in 1902. Sir Howard Grubb perfected the device in World War I.[3] Morgan Robertson (1861–1915) claimed[4] to have tried to patent the periscope: he described a submarine using a periscope in his fictional works.

Periscopes, in some cases fixed to rifles, served in World War I (1914–1918) to enable soldiers to see over the tops of trenches, thus avoiding exposure to enemy fire (especially from snipers).[5] The periscope rifle also saw use during the war – this was an infantry rifle sighted by means of a periscope, so the shooter could aim and fire the weapon from a safe position below the trench parapet.

During World War II (1939–1945), artillery observers and officers used specifically-manufactured periscope binoculars with different mountings. Some of them also allowed estimating the distance to a target, as they were designed as stereoscopic rangefinders.[citation needed]

Australian Light Horse troops using a periscope rifle, Gallipoli, 1915. Photograph by Ernest Brooks.

Armored vehicle periscopes

Tanks and armoured vehicles use periscopes: they enable drivers, tank commanders, and other vehicle occupants to inspect their situation through the vehicle roof. Prior to periscopes, direct vision slits were cut in the armour for occupants to see out. Periscopes permit view outside of the vehicle without needing to cut these weaker vision openings in the front and side armour, better protecting the vehicle and occupants.

A protectoscope is a related periscopic vision device designed to provide a window in armoured plate, similar to a direct vision slit. A compact periscope inside the protectoscope allows the vision slit to be blanked off with spaced armoured plate. This prevents a potential ingress point for small arms fire, with only a small difference in vision height, but still requires the armour to be cut.

In the context of armoured fighting vehicles, such as tanks, a periscopic vision device may also be referred to as an episcope. In this context a periscope refers to a device that can rotate to provide a wider field of view (or is fixed into an assembly that can), while an episcope is fixed into position.

Periscopes may also be referred to by slang, e.g. "shufti-scope".[6]

Gundlach and Vickers 360-degree periscopes

An important development, the Gundlach rotary periscope, incorporated a rotating top with a selectable additional prism which reversed the view. This allowed a tank commander to obtain a 360-degree field of view without moving his seat, including rear vision by engaging the extra prism. This design, patented by Rudolf Gundlach in 1936, first saw use in the Polish 7-TP light tank (produced from 1935 to 1939).

As a part of Polish–British pre-World War II military cooperation, the patent was sold to Vickers-Armstrong where it saw further development for use in British tanks, including the Crusader, Churchill, Valentine, and Cromwell models as the Vickers Tank Periscope MK.IV.

The Gundlach-Vickers technology was shared with the American Army for use in its tanks including the Sherman, built to meet joint British and US requirements. This saw post-war controversy through legal action: "After the Second World War and a long court battle, in 1947 he, Rudolf Gundlach, received a large payment for his periscope patent from some of its producers."[7]

The USSR also copied the design and used it extensively in its tanks, including the T-34 and T-70. The copies were based on Lend-Lease British vehicles, and many parts remain interchangeable. Germany also made and used copies.[7]

Periscopic gun-sights

Periscopic sights were also introduced during the Second World War. In British use, the Vickers periscope was provided with sighting lines, enabling front and rear prisms to be directly aligned to gain an accurate direction. On later tanks such as the Churchill and Cromwell, a similarly marked episcope provided a backup sighting mechanism aligned with a vane sight on the turret roof.

Later, US-built Sherman tanks and British Centurion and Charioteer tanks replaced the main telescopic sight with a true periscopic sight in the primary role. The periscopic sight was linked to the gun itself, allowing elevation to be captured (rotation being fixed as part of rotating turret). The sights formed part of the overall periscope, providing the gunner with greater overall vision than previously possible with the telescopic sight. The FV4201 Chieftain used the TESS (TElescopic Sighting System) developed in the early 1980s that was later sold as surplus for use on the RAF Phantom aircraft.[8][9]

Modern specialised AFV periscopes

In modern use, specialised periscopes can also provide night vision. The Embedded Image Periscope (EIP) designed and patented by Kent Periscopes provides standard unity vision periscope functionality for normal daytime viewing of the vehicle surroundings plus the ability to display digital images from a range of on-vehicle sensors and cameras (including thermal and low light) such that the resulting image appears "embedded" internally within the unit and projected at a comfortable viewing positions.

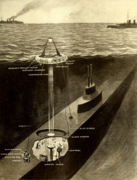

Periscopes allow a submarine, when submerged at a relatively shallow depth, to search visually for nearby targets and threats on the surface of the water and in the air. When not in use, a submarine's periscope retracts into the hull. A submarine commander in tactical conditions must exercise discretion when using his periscope, since it creates a visible wake (and may also become detectable by radar),[10][11] giving away the submarine's position.

Marie-Davey built a simple, fixed naval periscope using mirrors in 1854. Thomas H. Doughty of the United States Navy later invented a prismatic version for use in the American Civil War of 1861–1865.

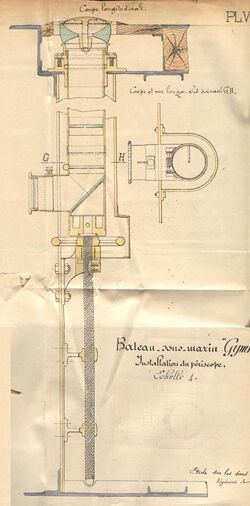

Submarines adopted periscopes early. Captain Arthur Krebs adapted two on the experimental French submarine Gymnote in 1888 and 1889. The Spanish inventor Isaac Peral equipped his submarine Peral (developed in 1886 but launched on September 8, 1888) with a fixed, non-retractable periscope that used a combination of prisms to relay the image to the submariner. (Peral also developed a primitive gyroscope for submarine navigation and pioneered the ability to fire live torpedoes while submerged.[12][unreliable source?])

The invention of the collapsible periscope for use in submarine warfare is usually credited[by whom?] to Simon Lake in 1902. Lake called his device the "omniscope" or "skalomniscope".[citation needed]

(As of 2009) modern submarine periscopes incorporate lenses for magnification and function as telescopes. They typically employ prisms and total internal reflection instead of mirrors, because prisms, which do not require coatings on the reflecting surface, are much more rugged than mirrors. They may have additional optical capabilities such as range-finding and targeting. The mechanical systems of submarine periscopes typically use hydraulics and need to be quite sturdy to withstand the drag through water. The periscope chassis may also support a radio or radar antenna.

Submarines traditionally had two periscopes; a navigation or observation periscope and a targeting, or commander's, periscope. Navies originally mounted these periscopes in the conning tower, one forward of the other in the narrow hulls of diesel-electric submarines. In the much wider hulls of (As of 2009 ) US Navy submarines the two operate side-by-side. The observation scope, used to scan the sea surface and sky, typically had a wide field of view and no magnification or low-power magnification. The targeting or "attack" periscope, by comparison, had a narrower field of view and higher magnification. In World War II and earlier submarines it was the only means of gathering target data to accurately fire a torpedo, since sonar was not yet sufficiently advanced for this purpose (ranging with sonar required emission of an acoustic "ping" that gave away the location of the submarine) and most torpedoes were unguided.

Twenty-first-century submarines do not necessarily have periscopes. The United States Navy's Virginia-class submarines and the Royal Navy's Astute-class submarines instead use photonics masts,[13] pioneered by the Royal Navy's HMS Trenchant, which lift an electronic imaging sensor-set above the water. Signals from the sensor-set travel electronically to workstations in the submarine's control center. While the cables carrying the signal must penetrate the submarine's hull, they use a much smaller and more easily sealed—and therefore less expensive and safer—hull opening than those required by periscopes. Eliminating the telescoping tube running through the conning tower also allows greater freedom in designing the pressure hull and in placing internal equipment.

Torpedoed Japanese destroyer Yamakaze photographed through periscope of USS Nautilus, 25 June 1942.

Aircraft use

Periscopes have also been used on aircraft for sections with limited view. The first known use of aircraft periscope was on the Spirit of St. Louis. The Vickers VC10 had a periscope that could be used on four locations of the aircraft fuselage,[14] V-Bombers such as the Avro Vulcan and Handley Page Victor[15] and the Nimrod MR1 as the "on top sight".[16] Various US bomber aircraft such as the B-52 used sextant periscopes for celestial navigation before the introduction of GPS.[17] This also allowed the aircrew to navigate without the use of an astrodome in the fuselage.[18][19] An emergency periscope was used on all Boeing 737 models manufactured before 1997 found under "Seat D" behind the over wing exit row to regulate the landing gear. High speed and hypersonic aircraft such as the North American X-15 used a periscope.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Walker, Bruce H. (2000). Optical Design for Visual Systems. SPIE Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-8194-3886-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=yprWx6DfqFUC&pg=PA117.

- ↑ The Submarine Periscope: An Explanation of the Principles Involved in Its Construction, Together with a Description of the Main Features of the Barr and Stroud Periscopes. Barr and Stroud Limited. 1928. https://books.google.com/books?id=bkOUoAEACAAJ.

- ↑ The History of the Periscope – Inventors. About.com

- ↑ Robertson, Morgan (March 26, 1913) The Schenectady Gazette, Friday morning, p. 19

- ↑ Willmott, H.P. (2003) First World War. Dorling Kindersley. p. 111. ISBN:1405300299

- ↑ Partridge, Eric (2006). A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. Routledge. pp. 1065–. ISBN 978-1-134-96365-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=IAjyQdFwh4UC&pg=PA1065.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Łukomski, Grzegorz and Stolarski, Rafał E. (1999) Nie tylko Enigma... Mjr Rudolf Gundlach (1892–1957) i jego wynalazek (Not Only Enigma... Major Rudolf Gundlach (1892–1957) and His Invention), Warsaw-London.

- ↑ "TESS :: David Gledhill". https://www.david-gledhill.co.uk/the-phantom/tess/.

- ↑ "The Way of the J. – British Phantom Aviation Group". https://bpag.co.uk/the-day-of-the-j/.

- ↑ Petty, Dan. "The US Navy – Fact File: AN/SPS-74(V) Radar Set" (in en). http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=2100&tid=1300&ct=2.

- ↑ Ousborne, Jeffrey; Griffith, Dale; Yuan, Rebecca W. (1997). "A Periscope Detection Radar". Johns Hopkins APL Technical Digest 18: 125. http://techdigest.jhuapl.edu/TD/td1801/ousbourn.pdf. Retrieved 2017-11-29.

- ↑ "El Arma Submarina Española". http://pedrocurto.com/1.html.

- ↑ War at Sea and in the Air. Britannica Educational Publishing. 1 November 2011. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-61530-753-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=TfOcAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA65.

- ↑ "Oddities & Innovations". https://www.vc10.net/Technical/oddities.html.

- ↑ "Bob's Tale of Phantoms – Victor XM715". https://www.victorxm715.co.uk/bobs-tale-of-phantoms/.

- ↑ Wilson, Michael (1968-06-13). "Hawker Siddeley Nimrod MR.1". FLIGHT International: 892. https://newsassets.cirium.com/Assets/GetAsset.aspx?ItemID=33320.

- ↑ "Periscope Aircraft Sextant | Pritzker Military Museum & Library | Chicago". https://www.pritzkermilitary.org/explore/museum/past-exhibits/citizen-soldier/periscopic-aircraft-sextant.

- ↑ Reichel, Jack. "Perscopic Sextant". https://www.ion.org/museum/item_view.cfm?cid=1&scid=1&iid=1.

- ↑ Campbell, Charles J.; McEachern, Lawrence J.; Marg, Elwin (1956). "Aircraft Flight by an Optical Periscope". Journal of the Optical Society of America 46 (11): 944. doi:10.1364/JOSA.46.000944. https://opg.optica.org/josa/abstract.cfm?uri=josa-46-11-944.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Periscope. |

- The Fleet Type Submarine Online: Submarine Periscope Manual United States Navy Navpers 16165, June 1979

- Simulation of a Periscope at NTNUJAVA Virtual Physics Laboratory

- Periscope used for Celestial Navigation in Petan.net

- Air Facts

- THE V-FORCE

- Air Navigation Periscope Sextants

- Periscope Sextant in a Douglas DC-8

|