Philosophy:Differential susceptibility

The differential susceptibility theory proposed by Jay Belsky[1] is another interpretation of psychological findings that are usually discussed according to the diathesis-stress model. Both models suggest that people's development and emotional affect are differentially affected by experiences or qualities of the environment. Where the Diathesis-stress model suggests a group that is sensitive to negative environments only, the differential susceptibility hypothesis suggests a group that is sensitive to both negative and positive environments. A third model, the vantage-sensitivity model,[2] suggests a group that is sensitive to positive environments only. All three models may be considered complementary, and have been combined into a general environmental sensitivity framework.[3]

Differential Susceptibility versus Diathesis-Stress

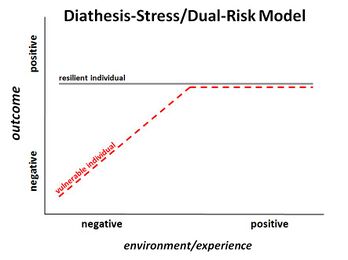

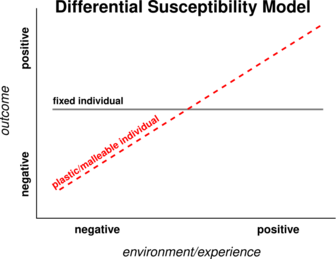

The idea that individuals vary in their sensitivity to their environment was historically framed in diathesis-stress[4] or dual-risk terms.[5] These theories suggested that some "vulnerable" individuals, due to their biological, temperamental and/or physiological characteristics (i.e., "diathesis" or "risk 1"), are more vulnerable to the adverse effects of negative experiences (i.e., "stress" or "risk 2"), while other "resilient" individuals are not affected by these negative experiences (see Figure 1).[6] The differential susceptibility hypothesis[7] and the related notion of biological sensitivity to context[8] suggested that individuals thought to be "vulnerable" are not only sensitive to negative environments, but also to positive environments (see Figure 2). Thus, according to the differential susceptibility hypothesis, some individuals are "susceptible" or "plastic", in that they are more influenced than others by environmental influences in a "for better and for worse" manner.[9]

Theoretical background

Belsky suggests that evolution might select for some children who are more plastic, and others who are more fixed in the face of, for example, parenting styles.

Belsky offers that ancestral parents, just like parents today, could not have known (consciously or unconsciously) which childrearing practices would prove most successful in promoting the reproductive fitness of offspring—and thus their own inclusive fitness. As a result, and as a fitness optimizing strategy involving bet hedging,[10] natural selection might have shaped parents to bear children varying in plasticity.[11] This way, if an effect of parenting had proven counterproductive in fitness terms, those children not affected by parenting would not have incurred the cost of developing in ways that ultimately proved "misguided".

Importantly, natural selection might favour genetic lines with both plastic and fixed developmental and affective patterns. In other words, there is value to having both kinds at once. In light of inclusive-fitness considerations, children who were less malleable (and more fixed) would have "resistance" to parental influence. This could be adaptable some times, and maladaptive other times. Their fixedness would not only have benefited themselves directly, but even their more malleable siblings indirectly. This is because siblings, like parents and children, have 50% of their genes in common. By the same token, had parenting influenced children in ways that enhanced fitness, then not only would more plastic offspring have benefited directly by following parental leads, but so, too, would their parents and even their less malleable siblings who did not benefit from the parenting they received, again for inclusive-fitness reasons. The overall effect may be to temper some of the variability in parenting. That is, to make more conservative bets.

This line of evolutionary argument leads to the prediction that children should vary in their susceptibility to parental rearing and perhaps to environmental influences more generally. As it turns out, a long line of developmental inquiry, informed by a "transactional" perspective,[12] has more or less been based on this unstated assumption.

Criteria for the testing of differential susceptibility

Belsky, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van IJzendoorn, (2007) delineated a series of empirical requirements—or steps—for evidencing the differential susceptibility hypothesis. Particularly they identify tests that distinguish differential susceptibility from other interaction effects including diathesis-stress/dual-risk.

While diathesis-stress/dual-risk arises when the most vulnerable are disproportionately affected in an adverse manner by a negative environment but do not also benefit disproportionately from positive environmental conditions, differential susceptibility is characterized by a cross-over interaction: the susceptible individuals are disproportionately affected by both negative and positive experiences. A further criterion that needs to be fulfilled to distinguish differential susceptibility from diathesis-stress/dual-risk is the independence of the outcome measure from the susceptibility factor: if the susceptibility factor and the outcome are related, diathesis-stress/dual-risk is suggested rather than differential susceptibility. Further, environment and susceptibility factor must also be unrelated to exclude the alternative explanation that susceptibility merely represents a function of the environment. The specificity of the differential-susceptibility effect is demonstrated if the model is not replicated when other susceptibility factors (i.e., moderators) and outcomes are used. Finally, the slope for the susceptible subgroup should be significantly different from zero and at the same time significantly steeper than the slope for the non- (or less-) susceptible subgroup.

Susceptibility markers and empirical evidence

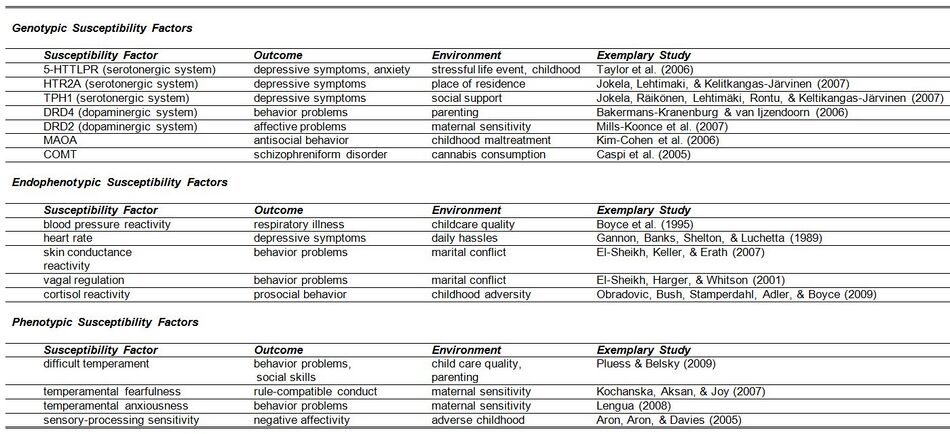

Characteristics of individuals that have been shown to moderate environmental effects in a manner consistent with the differential susceptibility hypothesis can be subdivided into three categories:[13] Genetic factors, endophenotypic factors, phenotypic factors.

Bakermans-Kranenburg and Van IJzendoorn (2006) were the first to test the differential susceptibility hypothesis as a function of Genetic Factors regarding the moderating effect of the dopamine receptor D4 7-repeat polymorphism (DRD4-7R) on the association between maternal sensitivity and externalizing behavior problems in 47 families. Children with the DRD4-7R allele and insensitive mothers displayed significantly more externalizing behaviors than children with the same allele but with sensitive mothers. Children with the DRD4-7R allele and sensitive mothers had the least externalizing behaviors of all whereas maternal sensitivity had no effect on children without the DRD4-7R allele.

Endophenotypic Factors have been examined by Obradovic, Bush, Stamperdahl, Adler and Boyce's (2010). They investigated associations between childhood adversity and child adjustment in 338 5-year-olds. Children with high cortisol reactivity were rated by teachers as least prosocial when living under adverse conditions, but most prosocial when living under more benign conditions (and in comparison to children scoring low on cortisol reactivity).

Regarding characteristics of the category of Phenotypic Factors, Pluess and Belsky (2009) reported that the effect of child care quality on teacher-rated socioemotional adjustment varied as a function of infant temperament in the case of 761 4.5-year-olds participating in the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (NICHD Early Child Care Research Network, 2005). Children with difficult temperaments as infants manifest the most and least behavior problems depending on whether they experienced, respectively, poor or good quality care (and in comparison to children with easier temperaments).

See also

- Diathesis-stress model

- Vantage sensitivity

- Environmental sensitivity

- Endophenotype

- Gene-environment interaction

- Gene-environment correlation

- Genotype

- Highly sensitive person

- Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- Norms of reaction

- Phenotype

- Resilience

- Temperament

- Therapygenetics

References

- ↑ Belsky, Jay (1997-07-01). "Variation in Susceptibility to Environmental Influence: An Evolutionary Argument". Psychological Inquiry 8 (3): 182–186. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0803_3. ISSN 1047-840X. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli0803_3.

- ↑ Pluess, Michael; Belsky, Jay (2013). "Vantage sensitivity: Individual differences in response to positive experiences." (in en). Psychological Bulletin 139 (4): 901–916. doi:10.1037/a0030196. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 23025924. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0030196.

- ↑ Pluess, Michael (2015). "Individual Differences in Environmental Sensitivity" (in en). Child Development Perspectives 9 (3): 138–143. doi:10.1111/cdep.12120. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/cdep.12120.

- ↑ Monroe & Simons, 1991; Zuckerman, 1999

- ↑ Sameroff, 1983

- ↑ Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian J.; van IJzendoorn, Marinus H. (2007). "Research Review: Genetic vulnerability or differential susceptibility in child development: the case of attachment" (in en). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 48 (12): 1160–1173. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01801.x. PMID 18093021. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01801.x.

- ↑ Belsky, Jay; Pluess, Michael (2009). "Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences." (in en). Psychological Bulletin 135 (6): 885–908. doi:10.1037/a0017376. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 19883141. http://doi.apa.org/getdoi.cfm?doi=10.1037/a0017376.

- ↑ Boyce, W. Thomas; Ellis, Bruce J. (2005). "Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary–developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity" (in en). Development and Psychopathology 17 (2): 271–301. doi:10.1017/S0954579405050145. ISSN 1469-2198. PMID 16761546. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/development-and-psychopathology/article/abs/biological-sensitivity-to-context-i-an-evolutionarydevelopmental-theory-of-the-origins-and-functions-of-stress-reactivity/2163EB3424FF3B40824916B17CA4DF9F.

- ↑ Belsky, Jay; Bakermans-Kranenburg, Marian J.; van IJzendoorn, Marinus H. (2007). "For Better and For Worse: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences" (in en). Current Directions in Psychological Science 16 (6): 300–304. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x. ISSN 0963-7214. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x.

- ↑ Philipi & Seger, 1989

- ↑ Belsky, 1997a, 2005

- ↑ Sameroff, 1983

- ↑ see Belsky & Pluess, 2009

Sources

- Belsky, J. (1997a). Variation in susceptibility to rearing influences: An evolutionary argument. Psychological Inquiry, 8, 182-186.

- Belsky, J. (1997b). Theory testing, effect-size evaluation, and differential susceptibility to rearing influence: the case of mothering and attachment. Child Development, 68(4), 598-600.

- Belsky, J. (2005). Differential susceptibility to rearing influences: An evolutionary hypothesis and some evidence. In B. Ellis & D. Bjorklund (Eds.), Origins of the social mind: Evolutionary Psychology and Child Development (pp. 139–163). New York: Guildford.

- Belsky, J., & Pluess, M. (2009). Beyond Diathesis-Stress: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Psychological Bulletin, 135(6), 885-908.

- Monroe, S. M., & Simons, A. D. (1991). Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin, 110(3), 406-425.

- Zuckerman, M. (1999). Vulnerability to psychopathology: A biosocial model. Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Sameroff, A. J. (1983). Developmental systems: Contexts and evolution. In P.Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 237–294). New York: Wiley.

- Boyce, W. T., & Ellis, B. J. (2005). Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity. Development and Psychopathology, 17(2), 271-301.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Research Review: genetic vulnerability or differential susceptibility in child development: the case of attachment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 48(12), 1160-1173.

- Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). For better and for worse: Differential Susceptibility to environmental influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 300-304.

- Philipi, T., & Seger, J. H. (1989). Hedging evolutionary bets, revisited. TREE, 4, 41-44.

- Taylor, S. E., Way, B. M., Welch, W. T., Hilmert, C. J., Lehman, B. J., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2006). Early family environment, current adversity, the serotonin transporter promoter polymorphism, and depressive symptomatology. Biological Psychiatry, 60(7), 671-676.

- Obradovic, J., Bush, N. R., Stamperdahl, J., Adler, N. E., & Boyce, W. T. (2010). Biological Sensitivity to Context: The Interactive Effects of Stress Reactivity and Family Adversity on Socio-emotional Behavior and School Readiness. Child Development, 81(1), 270-289.

- Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2009). Differential Susceptibility to Rearing Experience: The Case of Childcare. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 50(4), 396-404.

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2005). Child Care and Child Development: Results of the NICHD Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development. New York: Guilford Press.

- Jokela, M., Lehtimaki, T., & Keltikangas-Jarvinen, L. (2007). The influence of urban/rural residency on depressive symptoms is moderated by the serotonin receptor 2A gene. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B, 144B(7), 918-922.

- Jokela, M., Räikkönen, K., Lehtimäki, T., Rontu, R., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2007). Tryptophan hydroxylase 1 gene (TPH1) moderates the influence of social support on depressive symptoms in adults. Journal of Affective Disorders, 100(1-3), 191-197.

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2006). Gene-environment interaction of the dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) and observed maternal insensitivity predicting externalizing behavior in preschoolers. Developmental Psychobiology, 48(5), 406-409.

- Mills-Koonce, W. R., Proper, C. B., Gariepy, J. L., Blair, C., Garrett-Peters, P., & Cox, M. J. (2007). Bidirectional genetic and environmental influences on mother and child behavior: the family system as the unit of analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 19(4), 1073-1087.

- Kim-Cohen, J., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., Williams, B., Newcombe, R., Craig, I. W., et al. (2006). MAOA, maltreatment, and gene–environment interaction predicting children's mental health: new evidence and a meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 11(10), 903-913.

- Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., Cannon, M., McClay, J., Murray, R., Harrington, H., et al. (2005). Moderation of the effect of adolescent-onset cannabis use on adult psychosis by a functional polymorphism in the catechol-O-methyltransferase gene: longitudinal evidence of a gene X environment interaction. Biological Psychiatry, 57(10), 1117-1127.

- Boyce, W. T., Chesney, M., Alkon, A., Tschann, J. M., Adams, S., Chesterman, B., et al. (1995). Psychobiologic reactivity to stress and childhood respiratory illnesses: results of two prospective studies. Psychosomatic Medicine, 57(5), 411-422.

- Gannon, L., Banks, J., Shelton, D., & Luchetta, T. (1989). The mediating effects of psychophysiological reactivity and recovery on the relationship between environmental stress and illness. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 33(2), 167-175.

- El-Sheikh, M., Keller, P. S., & Erath, S. A. (2007). Marital conflict and risk for child maladjustment over time: skin conductance level reactivity as a vulnerability factor. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 35(5), 715-727.

- El-Sheikh, M., Harger, J., & Whitson, S. M. (2001). Exposure to interparental conflict and children's adjustment and physical health: the moderating role of vagal tone. Child Development, 72(6), 1617-1636.

- Pluess, M., & Belsky, J. (2009). Differential Susceptibility to Parenting and Quality Child Care. Developmental Psychology.

- Kochanska, G., Aksan, N., & Joy, M. E. (2007). Children's fearfulness as a moderator of parenting in early socialization: Two longitudinal studies. Developmental Psychology, 43(1), 222-237.

- Lengua, L. J. (2008). Anxiousness, frustration, and effortful control as moderators of the relation between parenting and adjustment in middle-childhood. Social Development, 17(3), 554-577.

- Aron, E. N., Aron, A., & Davies, K. M. (2005). Adult shyness: the interaction of temperamental sensitivity and an adverse childhood environment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(2), 181-197.

External links

|