Earth:Cultural ecology

| Anthropology |

|---|

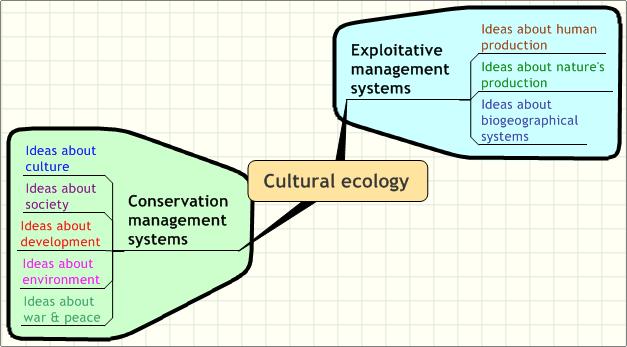

Cultural ecology is the study of human adaptations to social and physical environments.[1] Human adaptation refers to both biological and cultural processes that enable a population to survive and reproduce within a given or changing environment.[2] This may be carried out diachronically (examining entities that existed in different epochs), or synchronically (examining a present system and its components). The central argument is that the natural environment, in small scale or subsistence societies dependent in part upon it, is a major contributor to social organization and other human institutions. In the academic realm, when combined with study of political economy, the study of economies as polities, it becomes political ecology, another academic subfield. It also helps interrogate historical events like the Easter Island Syndrome.

History

Anthropologist Julian Steward (1902-1972) coined the term, envisioning cultural ecology as a methodology for understanding how humans adapt to such a wide variety of environments. In his Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution (1955), cultural ecology represents the "ways in which culture change is induced by adaptation to the environment." A key point is that any particular human adaptation is in part historically inherited and involves the technologies, practices, and knowledge that allow people to live in an environment. This means that while the environment influences the character of human adaptation, it does not determine it. In this way, Steward wisely separated the vagaries of the environment from the inner workings of a culture that occupied a given environment. Viewed over the long term, this means that environment and culture are on more or less separate evolutionary tracks and that the ability of one to influence the other is dependent on how each is structured. It is this assertion - that the physical and biological environment affects culture - that has proved controversial, because it implies an element of environmental determinism over human actions, which some social scientists find problematic, particularly those writing from a Marxist perspective. Cultural ecology recognizes that ecological locale plays a significant role in shaping the cultures of a region.

Steward's method was to:

- Document the technologies and methods used to exploit the environment to get a living from it.

- Look at patterns of human behavior/culture associated with using the environment.

- Assess how much these patterns of behavior influenced other aspects of culture (e.g., how, in a drought-prone region, great concern over rainfall patterns meant this became central to everyday life, and led to the development of a religious belief system in which rainfall and water figured very strongly. This belief system may not appear in a society where good rainfall for crops can be taken for granted, or where irrigation was practiced).

Steward's concept of cultural ecology became widespread among anthropologists and archaeologists of the mid-20th century, though they would later be critiqued for their environmental determinism. Cultural ecology was one of the central tenets and driving factors in the development of processual archaeology in the 1960s, as archaeologists understood cultural change through the framework of technology and its effects on environmental adaptation.

In anthropology

Cultural ecology as developed by Steward is a major subdiscipline of anthropology. It derives from the work of Franz Boas and has branched out to cover a number of aspects of human society, in particular the distribution of wealth and power in a society, and how that affects such behaviour as hoarding or gifting (e.g. the tradition of the potlatch on the Northwest North American coast).

As transdisciplinary project

One 2000s-era conception of cultural ecology is as a general theory that regards ecology as a paradigm not only for the natural and human sciences, but for cultural studies as well. In his Die Ökologie des Wissens (The Ecology of Knowledge), Peter Finke explains that this theory brings together the various cultures of knowledge that have evolved in history, and that have been separated into more and more specialized disciplines and subdisciplines in the evolution of modern science (Finke 2005). In this view, cultural ecology considers the sphere of human culture not as separate from but as interdependent with and transfused by ecological processes and natural energy cycles. At the same time, it recognizes the relative independence and self-reflexive dynamics of cultural processes. As the dependency of culture on nature, and the ineradicable presence of nature in culture, are gaining interdisciplinary attention, the difference between cultural evolution and natural evolution is increasingly acknowledged by cultural ecologists. Rather than genetic laws, information and communication have become major driving forces of cultural evolution (see Finke 2006, 2007). Thus, causal deterministic laws do not apply to culture in a strict sense, but there are nevertheless productive analogies that can be drawn between ecological and cultural processes.

Gregory Bateson was the first to draw such analogies in his project of an Ecology of Mind (Bateson 1973), which was based on general principles of complex dynamic life processes, e.g. the concept of feedback loops, which he saw as operating both between the mind and the world and within the mind itself. Bateson thinks of the mind neither as an autonomous metaphysical force nor as a mere neurological function of the brain, but as a "dehierarchized concept of a mutual dependency between the (human) organism and its (natural) environment, subject and object, culture and nature", and thus as "a synonym for a cybernetic system of information circuits that are relevant for the survival of the species." (Gersdorf/ Mayer 2005: 9).

Finke fuses these ideas with concepts from systems theory. He describes the various sections and subsystems of society as 'cultural ecosystems' with their own processes of production, consumption, and reduction of energy (physical as well as psychic energy). This also applies to the cultural ecosystems of art and of literature, which follow their own internal forces of selection and self-renewal, but also have an important function within the cultural system as a whole (see next section).

In literary studies

The interrelatedness between culture and nature has been a special focus of literary culture from its archaic beginnings in myth, ritual, and oral story-telling, in legends and fairy tales, in the genres of pastoral literature, nature poetry. Important texts in this tradition include the stories of mutual transformations between human and nonhuman life, most famously collected in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which became a highly influential text throughout literary history and across different cultures. This attention to culture-nature interaction became especially prominent in the era of romanticism, but continues to be characteristic of literary stagings of human experience up to the present.

The mutual opening and symbolic reconnection of culture and nature, mind and body, human and nonhuman life in a holistic and yet radically pluralistic way seems to be one significant mode in which literature functions and in which literary knowledge is produced. From this perspective, literature can itself be described as the symbolic medium of a particularly powerful form of "cultural ecology" (Zapf 2002). Literary texts have staged and explored, in ever new scenarios, the complex feedback relationship of prevailing cultural systems with the needs and manifestations of human and nonhuman "nature." From this paradoxical act of creative regression they have derived their specific power of innovation and cultural self-renewal.

German ecocritic Hubert Zapf argues that literature draws its cognitive and creative potential from a threefold dynamics in its relationship to the larger cultural system: as a "cultural-critical metadiscourse," an "imaginative counterdiscourse," and a "reintegrative interdiscourse" (Zapf 2001, 2002). It is a textual form which breaks up ossified social structures and ideologies, symbolically empowers the marginalized, and reconnects what is culturally separated. In that way, literature counteracts economic, political or pragmatic forms of interpreting and instrumentalizing human life, and breaks up one-dimensional views of the world and the self, opening them up towards their repressed or excluded other. Literature is thus, on the one hand, a sensorium for what goes wrong in a society, for the biophobic, life-paralyzing implications of one-sided forms of consciousness and civilizational uniformity, and it is, on the other hand, a medium of constant cultural self-renewal, in which the neglected biophilic energies can find a symbolic space of expression and of (re-)integration into the larger ecology of cultural discourses. This approach has been applied and widened in volumes of essays by scholars from over the world (ed. Zapf 2008, 2016), as well as in a recent monograph (Zapf 2016). Similar approaches have also been developed in adjacent fields, such as film studies (Paalman 2011).

In geography

In geography, cultural ecology developed in response to the "landscape morphology" approach of Carl O. Sauer. Sauer's school was criticized for being unscientific and later for holding a "reified" or "superorganic" conception of culture.[3] Cultural ecology applied ideas from ecology and systems theory to understand the adaptation of humans to their environment. These cultural ecologists focused on flows of energy and materials, examining how beliefs and institutions in a culture regulated its interchanges with the natural ecology that surrounded it. In this perspective humans were as much a part of the ecology as any other organism. Important practitioners of this form of cultural ecology include Karl Butzer and David Stoddart.

The second form of cultural ecology introduced decision theory from agricultural economics, particularly inspired by the works of Alexander Chayanov and Ester Boserup. These cultural ecologists were concerned with how human groups made decisions about how they use their natural environment. They were particularly concerned with the question of agricultural intensification, refining the competing models of Thomas Malthus and Boserup. Notable cultural ecologists in this second tradition include Harold Brookfield and Billie Lee Turner II. Starting in the 1980s, cultural ecology came under criticism from political ecology. Political ecologists charged that cultural ecology ignored the connections between the local-scale systems they studied and the global political economy. Today few geographers self-identify as cultural ecologists, but ideas from cultural ecology have been adopted and built on by political ecology, land change science, and sustainability science.

Conceptual views

Human species

Books about culture and ecology began to emerge in the 1950s and 1960s. One of the first to be published in the United Kingdom was The Human Species by a zoologist, Anthony Barnett. It came out in 1950-subtitled The biology of man but was about a much narrower subset of topics. It dealt with the cultural bearing of some outstanding areas of environmental knowledge about health and disease, food, the sizes and quality of human populations, and the diversity of human types and their abilities. Barnett's view was that his selected areas of information "....are all topics on which knowledge is not only desirable, but for a twentieth-century adult, necessary". He went on to point out some of the concepts underpinning human ecology towards the social problems facing his readers in the 1950s as well as the assertion that human nature cannot change, what this statement could mean, and whether it is true. The third chapter deals in more detail with some aspects of human genetics.[4]

Then come five chapters on the evolution of man, and the differences between groups of men (or races) and between individual men and women today in relation to population growth (the topic of 'human diversity'). Finally, there is a series of chapters on various aspects of human populations (the topic of "life and death"). Like other animals man must, in order to survive, overcome the dangers of starvation and infection; at the same time he must be fertile. Four chapters therefore deal with food, disease and the growth and decline of human populations.

Barnett anticipated that his personal scheme might be criticized on the grounds that it omits an account of those human characteristics, which distinguish humankind most clearly, and sharply from other animals. That is to say, the point might be expressed by saying that human behaviour is ignored; or some might say that human psychology is left out, or that no account is taken of the human mind. He justified his limited view, not because little importance was attached to what was left out, but because the omitted topics were so important that each needed a book of similar size even for a summary account. In other words, the author was embedded in a world of academic specialists and therefore somewhat worried about taking a partial conceptual, and idiosyncratic view of the zoology of Homo sapiens.

Ecology

Moves to produce prescriptions for adjusting human culture to ecological realities were also afoot in North America. Paul Sears, in his 1957 Condon Lecture at the University of Oregon, titled "The Ecology of Man," he mandated "serious attention to the ecology of man" and demanded "its skillful application to human affairs." Sears was one of the few prominent ecologists to successfully write for popular audiences. Sears documents the mistakes American farmers made in creating conditions that led to the disastrous Dust Bowl. This book gave momentum to the soil conservation movement in the United States.

Impact on nature

During this same time was J.A. Lauwery's Man's Impact on Nature, which was part of a series on 'Interdependence in Nature' published in 1969. Both Russel's and Lauwerys' books were about cultural ecology, although not titled as such. People still had difficulty in escaping from their labels. Even Beginnings and Blunders, produced in 1970 by the polymath zoologist Lancelot Hogben, with the subtitle Before Science Began, clung to anthropology as a traditional reference point. However, its slant makes it clear that 'cultural ecology' would be a more apt title to cover his wide-ranging description of how early societies adapted to environment with tools, technologies and social groupings. In 1973 the physicist Jacob Bronowski produced The Ascent of Man, which summarised a magnificent thirteen part BBC television series about all the ways in which humans have moulded the Earth and its future.

Changing the Earth

By the 1980s the human ecological-functional view had prevailed. It had become a conventional way to present scientific concepts in the ecological perspective of human animals dominating an overpopulated world, with the practical aim of producing a greener culture. This is exemplified by I. G. Simmons' book Changing the Face of the Earth, with its telling subtitle "Culture, Environment History" which was published in 1989. Simmons was a geographer, and his book was a tribute to the influence of W.L Thomas' edited collection, Man's role in 'Changing the Face of the Earth that came out in 1956.

Simmons' book was one of many interdisciplinary culture/environment publications of the 1970s and 1980s, which triggered a crisis in geography with regards its subject matter, academic sub-divisions, and boundaries. This was resolved by officially adopting conceptual frameworks as an approach to facilitate the organisation of research and teaching that cuts cross old subject divisions. Cultural ecology is in fact a conceptual arena that has, over the past six decades allowed sociologists, physicists, zoologists and geographers to enter common intellectual ground from the sidelines of their specialist subjects.

21st Century

In the first decade of the 21st century, there are publications dealing with the ways in which humans can develop a more acceptable cultural relationship with the environment. An example is sacred ecology, a sub-topic of cultural ecology, produced by Fikret Berkes in 1999. It seeks lessons from traditional ways of life in Northern Canada to shape a new environmental perception for urban dwellers. This particular conceptualisation of people and environment comes from various cultural levels of local knowledge about species and place, resource management systems using local experience, social institutions with their rules and codes of behaviour, and a world view through religion, ethics and broadly defined belief systems.

Despite the differences in information concepts, all of the publications carry the message that culture is a balancing act between the mindset devoted to the exploitation of natural resources and that, which conserves them. Perhaps the best model of cultural ecology in this context is, paradoxically, the mismatch of culture and ecology that have occurred when Europeans suppressed the age-old native methods of land use and have tried to settle European farming cultures on soils manifestly incapable of supporting them. There is a sacred ecology associated with environmental awareness, and the task of cultural ecology is to inspire urban dwellers to develop a more acceptable sustainable cultural relationship with the environment that supports them.

Educational framework

Cultural Core

To further develop the field of Cultural Ecology, Julian Steward developed a framework which he referred to as the cultural core. This framework, a “constellation” as Steward describes it,[5] organizes the fundamental features of a culture that are most closely related to subsistence and economic arrangements.

At the core of this framework is the fundamental human-environment relationship as it pertains to subsistence. Outside of the core, in the second layer, lies the innumerable direct features of this relationship - tools, knowledge, economics, labor, etc. Outside of that second, directly correlated layer is the less-direct but still influential layer, typically associated with larger historical, institutional, political or social factors.[6]

According to Steward, the secondary features are determined greatly by the “cultural-historical factors” and they contribute to building the uniqueness of the outward appearance of cultures when compared to others with similar cores. The field of Cultural Ecology is able to utilize the cultural core framework as a tool for better determining and understanding the features that are most closely involved in the utilization of the environment by humans and cultural groups.[7]

See also

- Cultural materialism

- Dual inheritance theory

- Ecological anthropology

- Environmental history

- Environmental racism

- Human behavioral ecology

- Political ecology

- Sexecology

References

- ↑ Frake, Charles O. (1962). "Cultural Ecology and Ethnography". American Anthropologist 64 (1): 53–59. doi:10.1525/aa.1962.64.1.02a00060. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ↑ Joralemon, David (2010). Exploring Medical Anthropology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. pp. 165. ISBN 978-0-205-69351-1.

- ↑ Duncan, James (2007). A Companion to Cultural Geography. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 14–22. ISBN 978-1405175654. https://books.google.com/books?id=mZf5bMKpV20C&pg=PA14.

- ↑ Barnett, Anthony (2016) (in en). The human species. Penguin Books Limited (1957). http://dspace.nehu.ac.in/handle/123456789/13669.

- ↑ Steward, Julian Haynes. “The Concept and Method of Cultural Ecology.” Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution , 1955.

- ↑ Steward, Julian Haynes. “The Concept and Method of Cultural Ecology.” Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution , 1955.

- ↑ Steward, Julian Haynes. “The Concept and Method of Cultural Ecology.” Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution , 1955.

Sources

- Barnett, A. 1950 The Human Species: MacGibbon and Kee, London.

- Bateson, G. 1973 Steps to an Ecology of Mind: Paladin, London

- Berkes, F. 1999 Sacred ecology: traditional ecological knowledge and resource management. Taylor and Francis.

- Bronowski, J. 1973 The Ascent of Man, BBC Publications, London

- Finke, P. 2005 Die Ökologie des Wissens. Exkursionen in eine gefährdete Landschaft: Alber, Freiburg and Munich

- Finke, P. 2006 "Die Evolutionäre Kulturökologie: Hintergründe, Prinzipien und Perspektiven einer neuen Theorie der Kultur", in: Anglia 124.1, 2006, p. 175-217

- Finke, P. 2013 "A Brief Outline of Evolutionary Cultural Ecology," in Traditions of Systems Theory: Major Figures and Contemporary Developments, ed. Darrell P. Arnold, New York: Routledge.

- Frake, Charles O. (1962) "Cultural Ecology and Ethnography" American Anthropologist. 64 (1: 53–59. ISSN 0002-7294.

- Gersdorf, C. and S. Mayer, eds. Natur – Kultur – Text: Beiträge zu Ökologie und Literaturwissenschaft: Winter, Heidelberg

- Hamilton, G. 1947 History of the Homeland: George Allen and Unwin, London.

- Hogben, L. 1970 Beginnings and Blunders: Heinemann, London

- Hornborg, Alf; Cultural Ecology

- Lauwerys, J.A. 1969 Man's Impact on Nature: Aldus Books, London

- Maass, Petra (2008): The Cultural Context of Biodiversity Conservation. Seen and Unseen Dimensions of Indigenous Knowledge among Q'eqchi' Communities in Guatemala. Göttinger Beiträge zur Ethnologie - Band 2, Göttingen: Göttinger Universitätsverlag ISBN:978-3-940344-19-9 online-version

- Paalman, F. 2011 Cinematic Rotterdam: The Times and Tides of a Modern City: 010 Publsihers, Rotterdam.

- Russel, W.M.S. 1967 Man Nature and History: Aldus Books, London

- Simmons, I.G. 1989 Changing the Face of the Earth: Blackwell, Oxford

- Steward, Julian H. 1972 Theory of Culture Change: The Methodology of Multilinear Evolution: University of Illinois Press

- Technical Report PNW-GTR-369. 1996. Defining social responsibility in ecosystem management. A workshop proceedings. United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service.

- Turner, B. L., II 2002. "Contested identities: human-environment geography and disciplinary implications in a restructuring academy." Annals of the Association of American Geographers 92(1): 52–74.

- Worster, D. 1977 Nature’s Economy. Cambridge University Press

- Zapf, H. 2001 "Literature as Cultural Ecology: Notes Towards a Functional Theory of Imaginative Texts, with Examples from American Literature", in: REAL: Yearbook of Research in English and American Literature 17, 2001, p. 85-100.

- Zapf, H. 2002 Literatur als kulturelle Ökologie. Zur kulturellen Funktion imaginativer Texte an Beispielen des amerikanischen Romans: Niemeyer, Tübingen

- Zapf, H. 2008 Kulturökologie und Literatur: Beiträge zu einem transdisziplinären Paradigma der Literaturwissenschaft (Cultural Ecology and Literature: Contributions on a Transdisciplinary Paradigm of Literary Studies): Winter, Heidelberg

- Zapf, H. 2016 Literature as Cultural Ecology: Sustainable Texts: Bloomsbury Academic, London

- Zapf, H. 2016 ed. Handbook of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology: De Gruyter, Berlin

External links

- Cultural and Political Ecology Specialty Group of the Association of American Geographers. Archive of newsletters, officers, award and honor recipients, as well as other resources associated with this community of scholars.

- Notes on the development of cultural ecology with an excellent reference list: Catherine Marquette

- Cultural ecology: an ideational scaffold for environmental education: an outcome of the EC LIFE ENVIRONMENT programme

|