Earth:West Mata

| West Mata | |

|---|---|

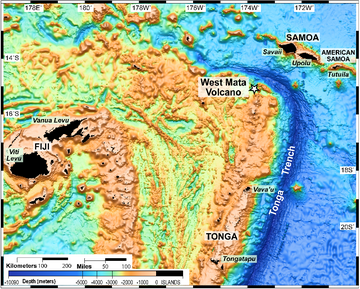

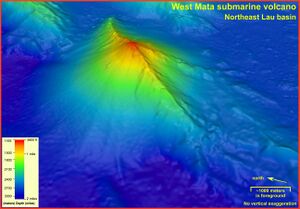

Bathymetry map of West Mata | |

| Summit depth | −1,174 m (−3,852 ft)[1] |

| Height | ~2,900 m (9,514 ft)[2] |

| Location | |

| Group | Mata volcanic group |

| Range | Tofua volcanic arc |

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 15°06′00″S 173°45′00″W / 15.1°S 173.75°W[1] |

| Country | Tonga |

| Geology | |

| Type | Fissure vent |

| Last activity | 2016[3] |

| History | |

| Discovery date | 2008[1] |

West Mata is an active submarine volcano located in the northeastern Lau Basin, roughly 200 km (124 mi) southwest of the Samoan Islands. It is part of the Tonga-Kermadec volcanic arc, which stretches from the North Island of New Zealand to Samoa. The volcano was first discovered in 2008 by scientists aboard the R/V Thompson research vessel, using sonar mapping and a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) to explore the seafloor. At the same time West Mata was discovered, multiple neighboring volcanoes—most of them hydrothermally active—were discovered as well, including Volcano O, Tafu-Maka, Northern Matas and East Mata.[4]

At the time of exploration, West Mata was the deepest undersea volcano eruption ever recorded, nearly −1,200 m (−3,937 ft) below the surface of the ocean. Following this record eruption, several research expeditions have been conducted to study the volcano and its history. Its study has provided important insights into the geology, chemistry, and biology of hydrothermal vents, as well as the dynamics of submarine volcanic systems.[5] The eruption was the deepest volcanic eruption ever found until 2015 when a segment of the Mariana Back-Arc erupted, producing lava flows and plumes.[6]

Geography

West Mata can be found in the northeastern portion of Tonga, in between Fiji and Samoa. It is located approximately 200 km (124 mi) southwest of the Samoan Islands and around 600 km (373 mi) northeast of the Lau Islands of Fiji.[1]

Structure

With data from bathymetric surveys, the structure of the West Mata volcano was made more clear. The West Mata vent has a common structure with most volcanic structures in the area, mostly dominated by a prominent rift zone that extends away from the summit, which is the peak of a conical structure with a circular base on the seafloor. Therefore, meanwhile the northeast and southwest flanks are rugged, the northwest and southeast flanks are rather smooth. This structure can also be seen on the East Mata volcano. The rift zones on the flanks consist of stair-like lava platforms piled on each other. The east-northeast rift zone curves towards the east as it deepens, and the west-southwest rift zone is west‐oriented towards its end. The summit area of West Mata is a narrow ridge aligned with those two rift zones. There are no structures similar to a crater at the summit although remnants of a former caldera seem to exist. Other conical volcanic features are limited and can only be found on the lower parts of both rift zones.[7]

Geologic setting

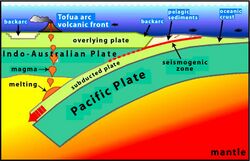

The Western Pacific Ocean is filled with many island-arc systems and trenches that come along them. Usually island arcs in this area are claimed to be chains of islands which are detached from continental masses. Between the island-arcs and the continental margins, still liquidated areas of seafloor are exposed out. These areas of seafloor are called back-arc basins. Most back-arc basins are rather shallow regions of ocean crust that are younger than the subducted crust in the adjacent trench. Back-arc basins can be found in between inactive and extinct volcanic arcs and the currently active volcanic island arcs that form as a result of the subduction. The Lau Basin, which West Mata can be found in, is one of the best examples of back-arc basins.[8]

The Lau Basin consists of an area of oceanic crust which separates the now remnant and extinct Lau-Colville Ridge volcanic arc and the Tofua volcanic arc with very active volcanism. The seaward rollback of the Tonga Trench is thought to be the main reason of the diverging action in this region. The basin lies above the westward-dipping seismically active area of subduction where the Pacific Plate slips under the Australian Plate.[9]

West Mata, specifically, is located in the northern part of the Lau Basin, defined as the Northeastern (NE) Lau Basin. The NE Lau Basin borders several spreading centers on the west, including the NE Lau Spreading Center, the Mangatolu Triple Junction and the Fonualei Rift Spreading Center from north to south, respectively. On the northern border of the basin can be found the area where the Kermadec-Tonga subduction zone transitions into a convergent strike-slip boundary. Meanwhile the plate boundary transitions, the faulting direction also changes from north-south to northwest-southeast directed faulting. The rollback of the trench which has also created the back-arc Lau basin created an area of oblique shear that has generated a whole zone of spreading centers and rifts with active hydrothermal vents along the northern boundary. West Mata can be considered one of them.[10]

The NE Lau Basin has one of the highest upper mantle temperatures in the world, has one of Earth's coolest slab thermal parameters (which is caused by the age and the speed of slab convergence), and has among the highest slab water flux values of any oceanic subduction zone. These factors cause the area's tectonism and volcanism to be complex compared to other places and cause the large amount of volcanic systems that exist in the NE Lau Basin.[11]

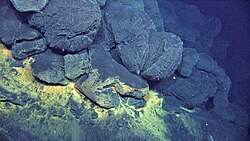

Composition

Most volcanic extrusions in the NE Lau Basin region structures usually erupt dacite lavas, some with unusual morphologies, which are quite rare in submarine volcanoes. Other than dacitic lavas, rift zones in the region have been also found to erupt basaltic andesite compositions.[11]

However, in the Mata volcano group, the main composition of eruptions in the Matas consists of mostly boninite, which is a type of extrusive rock usually seen in the Izu-Bonin Island Arc.[11]

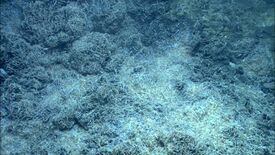

Fauna

West Mata and the surrounding NE Lau Basin are home to many hydrothermal vents, meaning that the area hosts a hydrothermal vent environment, which hosts organisms that use hydrothermal vents to supply their living needs. These environments can be seen in many continental margins around the world.[12]

Hydrothermal ecology

The hydrothermal ecology of the Lau Basin is home to many endemic organisms, including the Lamellibrachia columna which shows similarity to Lamellibrachia satsuma that can be found in Japan;[13] Neobrachylepas relica, a close relative to the Brachylepadomorpha which was extinct since the Miocene;[14] and more. In West Mata, these organisms were not observed, pointing to the diversity of the Lau Basin's ecology. Instead, a hydrothermal environment consisting of three species of polychaete worms, two species of shrimp, three species of crabs and eelpouts was observed. During the eruption of 2008–10 it was observed that there were only large groups of opaepele shrimp on the seamount and the normal hydrothermal vent community was not present.[15]

Activity

The volcano has known to be both hydrothermally and eruptively active in recent history, the most active in between its neighboring volcanoes.[15] According to depth differences in West Mata's flanks, it was pointed out that West Mata had an eruption which lasted from 1996 to 2008 at a depth of 2,750 m (9,022 ft).[16]

In November 2008, during a hydrographic survey in the region, an intense hydrothermal plume over the summit of West Mata consisting of high levels of hydrogen and pieces of volcanic glass was detected, which suggested it was likely erupting.[17] Following this event, 6 months later, the 2009 Northeast Lau Response Cruise was led by the NOAA on board the R/V Thomas G. Thompson and carrying ROV Jason to deploy it in the area. During the cruise, 5 dives were executed onto West Mata. In the first dive, an active eruption of glowing molten lava along with explosions were observed at a depth of around 1,205 m (3,953 ft) near the summit of the volcano; this eruption site was named Hades. In the rest of the dives, more parts of West Mata were uncovered, including the erupting area of the summit, which was discovered to extend 1,000 m (3,281 ft) along the summit. The second main vent on the summit was later named Prometheus.[15][18]

Both vents, Hades and Prometheus, had different eruption styles. Hades was erupting with frequent magma bursts; meanwhile, Prometheus was showing a rapid degassing eruption. These eruptions both generated broadband signals which were recorded by hydrophones that were set up in the area in 2009.[19] Elevation changes at the flanks of the volcano were observed by hydrophones and bathymetric surveys at the area over the years, pointing out that West Mata has had many landslides at the years of the eruption.[20]

Following the main eruption, several papers suggest that in 2010–11 lava flows were recorded that covered an area of 1,300 m (4,265 ft) by 700 m (2,297 ft) at 2,950 m (9,678 ft) below sea level according to bathymetry depth differences.[3] The same papers also note that a year later, West Mata had an eruption between 2012 and 2016 at a depth of 2,650 m (8,694 ft). It was discovered the same way as the 2010–11 eruption, via bathymetry depth differences and bathymetric surveys.[3]

See also

- Niuatahi – another volcano in the Northeastern Lau Basin

- List of volcanoes in Tonga

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "West Mata". Smithsonian Institution. https://volcano.si.edu/volcano.cfm?vnum=243130.

- ↑ Murch et al. 2022, p. 3.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Chadwick Jr. et al. 2019, p. 14.

- ↑ Merle, S. G.; Embley, B.; Lupton, J.; Baker, E.; Resing, J.; Lilley, M. (2008). Northeast Lau Basin, R/V Thompson Expedition TN227, November 13-28, 2008, Apia to Apia, Western Samoa (Report). NOAA. p. 34. https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/eoi/laubasin/documents/tn227-nelau-report-final.pdf. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ↑ "Deep Ocean Volcanoes". Ocean Today NOAA. https://oceantoday.noaa.gov/deepoceanvolcanoes/.

- ↑ "Eruption of the world's deepest undersea volcano". EarthSky. 25 October 2018. https://earthsky.org/earth/recent-undersea-volcanic-eruption-deepest-known/.

- ↑ Clague et al. 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Hawkins 1995, p. 64.

- ↑ Hawkins 1995, p. 63.

- ↑ Embley & Rubin 2018, p. 2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Embley & Rubin 2018, p. 3.

- ↑ Southward 1991, p. 859.

- ↑ Southward 1991, p. 866.

- ↑ Newman & Yamaguchi 1995, p. 222.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Seamount Eruptions: Windows to the Development of Hydrothermal Vent Biological Communities". NOAA. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/12fire/logs/sept21/sept21.html.

- ↑ Chadwick Jr. et al. 2019, p. 16.

- ↑ Chadwick Jr. et al. 2019, p. 2.

- ↑ "Northeast Lau Response Cruise (NELRC)". NOAA. https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/09laubasin/welcome.html.

- ↑ Dziak et al. 2015, p. 1482.

- ↑ Caplan-Auerbach et al. 2014, p. 5930.

Sources

- Clague, D. A.; Paduan, J. B.; Caress, D. W.; Thomas, H.; Chadwick Jr., W. W.; Merle, S. G. (2011). "Volcanic morphology of West Mata Volcano, NE Lau Basin, based on high-resolution bathymetry and depth changes". Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 12 (11): 0–21. doi:10.1029/2011GC003791. Bibcode: 2011GGG....12OAF03C. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1029/2011GC003791.

- Hawkins, J. W. (1995). "The Geology of the Lau Basin". Backarc Basins 578: 63–138. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-1843-3_3. ISBN 978-1-4613-5747-6. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012821X21005847.

- Embley, R. W.; Rubin, K. H. (2018). "Extensive young silicic volcanism produces large deep submarine lava flows in the NE Lau Basin". Bulletin of Volcanology 80 (4): 0–23. doi:10.1007/s00445-018-1211-7. Bibcode: 2018BVol...80...36E. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00445-018-1211-7.

- Murch, A. P.; Portner, R. A.; Rubin, K. H.; Clague, D. A. (2022). "Deep-subaqueous implosive volcanism at West Mata seamount, Tonga". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 578 (1): 0–43. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2021.117328. Bibcode: 2022E&PSL.57817328M. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0012821X21005847.

- Southward, E. C. (1991). "Three new species of Pogonophora, including two vestimentiferans, from hydrothermal sites in the Lau Back-arc Basin (Southwest Pacific Ocean)". Journal of Natural History 25 (4): 859–881. doi:10.1080/00222939100770571. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00222939100770571.

- Newman, W. A.; Yamaguchi, T. (1995). "A new sessile barnacle (Cirripedia, Brachylepadomorpha) from the Lau Back-Arc Basin, Tonga; first record of a living representative since the Miocene". Bulletin du Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Section A 17 (1): 221–244. doi:10.5962/p.290349. https://sciencepress.mnhn.fr/en/periodiques/bulletin-du-museum-national-d-histoire-naturelle-4eme-serie-section-zoologie-biologie-et-ecologie-animales/17/3-4/un-nouveau-cirripede-sessile-cirripedia-brachylepadomorpha-de-l-arc-posterieur-du-bassin-de-lau-tonga-premiere-observation-d-un.

- Chadwick Jr., W. W.; Rubin, K. H.; Merle, S. G.; Bobbitt, A. M.; Kwasnitschka, T.; Embley, R. W. (2019). "Recent Eruptions Between 2012 and 2018 Discovered at West Mata Submarine Volcano (NE Lau Basin, SW Pacific) and Characterized by New Ship, AUV, and ROV Data". Frontiers in Marine Science 6 (2019): 0–25. doi:10.3389/fmars.2019.00495.

- Caplan-Auerbach, J.; Dziak, R. P.; Bohnenstiehl, D. R.; Chadwick Jr., W. W.; Lau, T. K. (2014). "Hydroacoustic investigation of submarine landslides at West Mata volcano, Lau Basin". Geophysical Research Letters 41 (16): 5927–5934. doi:10.1002/2014GL060964. Bibcode: 2014GeoRL..41.5927C. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2014GL060964.

- Dziak, R. P.; Bohnenstiehl, D. R.; Baker, E. T.; Matsumoto, H.; Caplan-Auerbach, J.; Embley, R. W.; Merle, S. G.; Walker, S. L. et al. (2015). "Long-term explosive degassing and debris flow activity at West Mata submarine volcano". Geophysical Research Letters 42 (5): 1480–1487. doi:10.1002/2014GL062603. Bibcode: 2015GeoRL..42.1480D. https://agupubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/2014GL062603.

|