Earth:Mountain warfare

Mountain warfare or alpine warfare is warfare in mountains or similarly rough terrain. The term encompasses military operations affected by the terrain, hazards, and factors of combat and movement through rough terrain, as well as the strategies and tactics used by military forces in these situations and environments.

Mountain ranges are of strategic importance since they often act as a natural border and may also be the origin of a water source such as the Golan Heights. Attacking a prepared enemy position in mountain terrain generally requires a greater ratio of attacking soldiers to defending soldiers than a war conducted on level ground. Mountains present natural hazards such as lightning, strong gusts of wind, rockfalls, avalanches, snowpacks, ice, extreme cold, and glaciers with their crevasses; in these ways, it can be similar to cold-weather warfare. The generally uneven terrain and the slow pace of troop and material movements are additional threats to combatants. Movement, reinforcements, and medical evacuation up and down steep slopes and areas in which even pack animals cannot reach involves an enormous exertion of energy.[1]

History

Second Punic War

In 218 BC (DXXXVI AUC), the Carthaginian army commander Hannibal marched troops, cavalry and African elephants across the Alps in an effort to conquer Rome by approaching it from north of the Italian Peninsula. The Roman government was complacent because the Alps were viewed as a secure natural obstacle to would-be invaders. In December 218 BC, the Carthaginian forces defeated Roman troops, in the north, with the use of elephants. Many elephants did not survive the cold weather and disease typical of the European climate. Hannibal's army fought Roman troops in Italy for 15 years but failed to conquer Rome. Carthage was ultimately defeated by Roman general Scipio Africanus at Zama in North Africa in 202 BC (DLII AUC).[2]

Early history

The term mountain warfare is said to have come about in the Middle Ages after the European monarchies found it difficult to fight the Swiss armies in the Alps because the Swiss fought in smaller units and took vantage points against a huge unmaneuverable army. Similar styles of attack and defence were later employed by guerrillas, partisans and irregulars, who hid in the mountains after an attack, which made it challenging for an army of regulars to fight back. In Napoleon Bonaparte's Italian campaign, Suvorov's Italian and Swiss expedition and the 1809 rebellion in Tyrol, mountain warfare played a large role.[3]

Another example of mountain warfare was the Crossing of the Andes, which was carried out by the Argentinean Army of the Andes (Spanish: Ejército de los Andes), commanded by General José de San Martín in 1817. One of the divisions climbed mountains surpassing 5000 m in height.[4]

The Caucasian War was a 19th century military conflict between the Russian Empire and various peoples of the North Caucasus who resisted subjugation during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus.

The first British invasion of Afghanistan ended in disaster in 1842, when 16,000 British soldiers and camp followers were massacred as they retreated through the Hindu Kush back to India.[5]

World War I

Mountain warfare came to the fore once again during World War I, when some of the nations that were involved in the war had mountain divisions that had not been tested. The Austro-Hungarian defence repelled Italian attacks by taking advantage of the terrain in the Julian Alps and the Dolomites, where frostbite and avalanches proved deadlier than bullets.[6] During the summer of 1918, the Battle of San Matteo took place on the Italian front and was fought at the highest elevation of any during the war. In December 1914, another offensive was launched by the Ottoman supreme commander Enver Pasha with 95,000–190,000 troops against the Russia ns in the Caucasus. Insisting on a frontal attack against Russian positions in the mountains in the heart of winter, the result was devastating, and Enver lost 86% of his forces.[7]

World War II

Examples of mountain warfare used during World War II include the Battles of Narvik, Battle of the Caucasus, Kokoda Track campaign, Battle of Attu, Operation Rentier, Operation Gauntlet, Operation Encore, and the British defence at the Battle of Hong Kong.

One ambush tactic used against the Germans during the Battles of Narvik utilised hairpin bends. Defenders would position themselves above them and open fire when attackers reached a certain point below, parallel to themselves. This would force the attackers to: retreat; to continue under fire; or to attempt to climb the mountain another way. The tactic could be planned in advance, or employed by a retreating force.[8]

Another tactic utilised was the 'ascending platoon attack'. Attackers would scout higher enemy positions from the ground, aided by bad weather or poor visibility. A Light Machine Gun (LMG) team would open fire towards the high enemy position from a distance, offering cover for the remaining soldiers to gradually advance.[8]

Kashmir conflicts

Since the Partition of India in 1947, India and Pakistan have been in conflict over the Kashmir region. They have fought two wars and numerous additional skirmishes or border conflicts in the region.[9] Kashmir is located in the Himalayas, the highest mountain range in the world.[10]

The first hostilities between the two nations, during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, showed that both were ill-equipped to fight in biting cold, let alone at the highest altitudes in the world.[11] During the Sino-Indian War of 1962, hostilities broke out between India and China in the same area.[9]

The subsequent Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 between India and Pakistan was mainly fought in Kashmir's valleys, rather than the mountains themselves, but several mountain battles took place. During the Kargil War (1999), Indian forces sought to flush out opponents who had captured high mountain posts. That proxy war was the only modern war that was fought exclusively in the mountains.[12] After the Kargil War, the Indian Army implemented specialist training on artillery use in the mountains, where ballistic projectiles have different characteristics than at sea level.[13]

Falklands War

Most of the Falklands War took place on hills in semi-Arctic conditions on the Falkland Islands. However, during the opening stage of the war, there was military action on the bleak mountainous island of South Georgia, where a British expedition sought to eject occupying Argentine forces. South Georgia is a periantarctic island, and the conflict took place during the southern winter and so Alpine conditions prevailed almost down to sea level. The operation (codenamed Operation Paraquet) was unusual in that it combined aspects of long-range amphibious warfare, arctic warfare and mountain warfare. It involved several ships, special forces troops and helicopters.[14]

War in Afghanistan

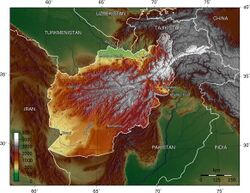

Throughout history but especially since 1979, many mountain warfare operations have taken place throughout Afghanistan. Since the coalition invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, they have been primarily in the eastern provinces of Kunar and Nuristan.[15]

Kunar and eastern Nuristan are strategic terrain since the area constitutes a major infiltration route into Afghanistan, and insurgents can enter the provinces from any number of places along the border with Pakistan to gain access to a vast network of river valleys. In that part of Afghanistan (Regional Command East), the US military adopted a hybrid style of mountain warfare incorporating counterinsurgency (COIN) theory in which the population is paramount as the center of gravity in the fight.[16]

In counterinsurgency, seizing and holding territory are less important than avoiding civilian casualties. The primary goals of counterinsurgency are to secure the backing of the populace and thereby to legitimize the government, rather than to focus on militarily defeating the insurgents. Counterinsurgency doctrine has proved difficult to implement in Kunar and Nuristan. In the sparsely-populated mountain regions of eastern Afghanistan, strategists have argued for holding the high ground, a tenet of classical mountain warfare. The argument suggests that if the counterinsurgent does not deny the enemy the high ground, the insurgents can attack at will. In Kunar and Nuristan, US forces continued to pursue a hybrid style of counterinsurgency warfare, with its focus on winning hearts and minds, and mountain warfare, with the US forces seizing and holding the high ground.

Training

The expense of training mountain troops precludes them from being on the order of battle of most armies except those that reasonably expect to fight in such terrain. Mountain warfare training is arduous and in many countries the exclusive preserve of elite units such as special forces or commandos, which as part of their remit should have the ability to fight in difficult terrain such as the Royal Marines. Regular units may also occasionally undertake training of this nature.

See also

- List of mountain warfare forces

- Cold-weather warfare

References

- ↑ "Research report". www.rand.org. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR700/RR718/RAND_RR718.pdf.

- ↑ Ball, Philip (April 3, 2016). "The truth about Hannibal's route across the Alps". https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/apr/03/where-muck-hannibals-elephants-alps-italy-bill-mahaney-york-university-toronto.

- ↑ "PBS - Napoleon: Napoleon at War". https://www.pbs.org/empires/napoleon/n_war/campaign/page_1.html.

- ↑ "Data". www.loc.gov. https://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/cs/pdf/CS_Colombia.pdf.

- ↑ Stewart, Terry. "Britain's Retreat from Kabul 1842". Historic UK. https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Britains-Retreat-From-Kabul-1842/.

- ↑ Chow, Brian Mockenhaupt, Stefen. "The Most Treacherous Battle of World War I Took Place in the Italian Mountains". https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/most-treacherous-battle-world-war-i-italian-mountains-180959076/.

- ↑ "Siachen Glacier: Mountain Warfare". http://www.siachenglacier.com/mountain-warfare.html.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Bull, Stephen (2013) (in en). World War II Winter and Mountain Warfare Tactics. Great Britain: Osprey Publishing. pp. 20–21. ISBN 9781849087131.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "The Kashmir conflict: How did it start?". March 2, 2019. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/2019/03/kashmir-conflict-how-did-it-start/.

- ↑ "Himalayan Peaks". https://www.its.caltech.edu/~rchary/trek/tibet/everest/peaks.html.

- ↑ "Indo-Pakistani Conflict of 1947-48". https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/world/war/indo-pak_1947.htm.

- ↑ Abbas, Zaffar (July 30, 2016). "When Pakistan and India went to war over Kashmir in 1999". http://herald.dawn.com/news/1153481.

- ↑ "Archived copy". https://www.vifindia.org/sites/default/files/weapons-and-missiles-in-the-indian-environment.pdf.

- ↑ "Sink the Belgrano", Mike Rossiter, 2007, Transworld, London, pp 189–233

- ↑ "On the ground in Afghanistan". 2012. https://www.marines.mil/Portals/1/Publications/On%20The%20Ground%20In%20Afghanistan.pdf.

- ↑ Marks, Thomas A. (2005). "Counterinsurgency and Operational Art". Low Intensity Conflict & Law Enforcement 13 (3): 168–211. doi:10.1080/09662840600560527.

Sources

- Frederick Engels, (January 27, 1857) "Mountain Warfare in the Past and Present" New York Daily Tribune MECW Volume 15, p 164

Further reading

- Govan, Thomas P. (1946-09-01). "Training for mountain and winter warfare". [Washington, D.C.]: Historical Section, Army Ground Forces. http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA353746. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

- Pierce, Scott W. (2008-05-22). "Mountain and cold weather warfighting: critical capability for the 21st century". Fort Leavenworth, Kans.: School of Advanced Military Studies, United States Army Command and General Staff College. http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADA485557. Retrieved 2011-01-28.

External links

- Official page of documentary film GLOBAL WARNING on the Mountain War 1915–1918 Global Warning

- Mountain War in World War I The war in the Italian Dolomites (Italian)

- Historic films showing Mountain Warfare in World War I at europeanfilmgateway.eu

- Mountain Combat World War II Militaria: Combat Lessons

- High Altitude Warfare School of the Indian Army [1]

- Official Italian Army website page on Alpine Troops Command [2]

- Official page of 11th Mountain Infantry Battalion (Brazil)[3]

|