Social:Otoro language

| Otoro | |

|---|---|

| Utoro | |

| Native to | Sudan |

| Region | Nuba Hills |

| Ethnicity | Otoro Nuba |

Native speakers | 10,000 (2001)[1] |

Niger–Congo

| |

| Dialects |

|

| Latin | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | otr |

| Glottolog | otor1240[2] |

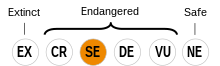

Otoro is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

The Otoro language classifies in to the Haiban Language family which belongs to the Kordofanian Languages and therefore it is a part of the Niger-Congo Languages.[3] In a smaller view the Otoro is a segment of the „central branch “[4] from the so-called Koalib-Moro Groupe of the Languages which are spoken in the Nuba Mountains. The Otoro language is spoken within the geographical regions encompassing Kuartal, Zayd and Kauda in Sudan.[4] The precise number of Otoro speakers is unknown, though current evaluates suggest it to be exceeding 15000 individuals.[5]

Every illustration provided in this article will be depicted in community orthography, using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). However, some similar sounds are not further distinguished and represented as one. Therefore, the sounds ˈɪˈ, ˈiˈ and ˈɪ̈ˈ will be collectively denoted as ˈiˈ, ˈaˈ and ˈɑˈ as ˈaˈ, ˈɔːˈ and ˈɔˈ as ˈɔˈ, ˈoˈ and ˈo̜ˈ as ˈoˈ and ˈuˈ and ˈʊˈ as ˈuˈ.[6]

Name

To outsiders, the language is called „Otoro “. The local name of the language is „Dhitoɽo “. Otoro speakers are referred to as „Litoɽo “ (plural) and the area is called „Otoɽo “.[4]

Language Varieties

Otoro shows linguistic diversity through the presence of three primary varieties, each named after the respective mountain ranges within which these linguistic variations are observed.

The Kwara variety is the most prominently represented in the Otoro language, on which Stevenson’s book “Tira and Otoro ” is based. Furthermore, in the Kwara mountain group, the town of Sabun, known as the home of the Mek, holds a high political status as Mek denotes the chief of the Otoro.

The native speakers on the hill chains Kijama and Kwijur use remarkably similar varieties. Consequently, in this article it is viewed as one and introduced as the Kwijur variety.

The third vernacular is the Orombe variety. It is used in the Orombe and Girindi hills. Linguistically the Orombe variety has similarities of both the Kwara and Kwijur variety.[5]

Phonology

This section is based on all the Otoro varieties and will demonstrate the phonology of the Otoro Language with the focus on Vowels, Consonants, Stress and intonation.

Vowels

The three Otoro varieties utilize a system of thirteen vowels. In a more comprehensive script, 'i' will also cover 'ɪ' and ˈɪ̈ˈ, 'a' will cover both 'a' and 'ɑ', 'u' will include 'ʊ' and 'o' will also involve 'o̜', resulting in a total of nine primary vowels.[7]

| Front

short |

Central

Short |

Back

short Long | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closed | i

ɪ |

ɪ̈ | u

ʊ |

| Closed-mid | e | ö | o

o̜ |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ə | ɔ ɔː |

| Open | a | ɑ |

Vowel Change

It is known that vowel changes are not only present but also play a crucial role in verb conjugation. In general vowel change needs further exploration within the Otoro context.[8]

Consonants

The following table shows all the noted consonants in the Otoro dialects.[9]

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Dental | Alveolar

(retroflex) |

Palatal | Velar | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p, b | th, dh | t,d | c,j | k, g | |

| Implosive | ɗ | |||||

| Fricative | ʋ | v | ð | |||

| Affricates | tr, dr | |||||

| Nasal | n | ny | ŋ | |||

| Liquids, etc. | ɽ | l, r | y | w |

Several of the consonants mentioned in the table exhibit peculiarities. For instance, the bilabial fricative 'ʋ' is absent in the Kwijur variety and appears merely as a variant of 'm' or 'v' in the Kwara variety. On the country, affricates occur solely in the Kwijur variety. Regarding closed syllables, the majority conclude in a nasal or liquid consonant. In the Kwara variety one will see the nasal 'ny'/'ŋ' far less than in the other two dialects. In general, Affricates, plosives, the fricatives 'ʋ' and 'v' and implosives may not be syllable-final.[9]

Consonant combinations

In Otoro, the language employs compounds involving the semi-vowel 'w' along with dentals, liquids and nasals. However, not all the dialects share the same set of combinations.[10]

Compounds with liquids:

These are first incountered in Orombe and Kwijur.

'lr' , 'lrk' , 'lrkw' , 'lɽ' , 'ld' , 'lð' , 'ldr' , 'lth' , 'dr' , 'ŋɽ' , 'rn' , 'rk' , 'rkw'

English Kwara Kwijur Orombe

Hill ldori lrɔgɔm lrɔgwɔm

The compounds with nasals:

These are mostly present in Kwijur.

'ŋɽ', 'ŋw', 'mb', 'nd', 'ŋg',…

English Kwara Kwijur Orombe

Rifle, gun almudu almundu almudu[11]

Compound with semi-vowel 'w':

These are found in every Otoro dialect.

'kw', 'gw', 'ŋw'

English Kwara Kwijur Orombe

Fly kwal kwalum kwal[12]

Stress and Intonation

Stress and the emphasis of louder or stronger sounds are commonly used in the Otoro language. However, words which are only determined by tone are rare. A distinct pattern of the stress in this language has not yet been established, although Stevenson says that the stress often falls on the last syllable. In instance, where a word has a final consonant, the stress typically occurs on the last syllable. Conversely, many dissyllabic words tend to stress on the first syllable.[13]

| English | Kwara | Kwijur | Orombe |

|---|---|---|---|

| buttock | 'gwutu | 'gwuthu | 'gwutu |

| many | gwu'tu | gwu'tu | gwu'tu |

| to open | 'iðu | 'iðu | 'iðhu |

| head | l'ɽa | l'ɽa | l'ɽa |

Morphology

Otoro is an agglutinative language which means it is a type of language characterized by adding affixes to the root or stem of a word. Also, Otoro does not have a grammatical gender, but does have noun classes. The etymological roots primarily manifest as monosyllabic or dissyllabic structures.[4] The syllables primarily contain either a vowel-consonant pairing or a vowel combined with a sequence of consonants. Syllables in this language are mostly open but specific consonants may form a closed syllable, characterized by a short vowel ending. This structure is notably more frequent in Kwijur and Orombe as compared to Kwara.[15] The nouns in Otoro are grouped in twelve noun-classes, with specific prefixes employed to construct the noun and differentiate between singular and plural. The layout in these prefixes is unique to each class. To achieve agreement with the noun, verbs and qualificatives employ concord prefixes. Those concord prefixes depend on the specific noun-classes and mirror the prefixes used for the corresponding noun within the same noun class. This pattern is recognized as “alliterative concord ”.[4]

Nouns

As mentioned before, Otoro nouns fall into twelve different classes, each with its own clear distinctions. This classification system is quite transparent and forms a construction. The noun-classes are marked both numerically and through given titles, to make an approach to understanding the classifications better. The designations corresponding to each class are displayed in the chart below. In each noun-class of Otoro, every noun is assigned two prefixes, distinctly indicating whether the word is in its singular or plural form. In the chart below the concord prefixes which come with verbs and qualificatives agreeing to the noun are also shown due to their similar configuration.[16] Exceptions, clarifications or outbreaks of the pattern will be demonstrated beneath the table.

| Class | Class Prefix

sing. pl. |

Example

Kwara |

English

Translation |

Concord

Prefix sing. pl. |

Example

Kwara |

English

Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1."Person"/

"Living Things" 1.a (suffix) |

gw- l-

gwu- li- -ŋa |

gwɛlɛ

lɛlɛ gwutoɽo litoɽo baba babaŋa |

Chief

Chiefs Otoro Person Otoro Persons Father Fathers |

gw- l- | gwiji gwiŋir

baba gwi |

A good person

My father |

| 2."Nature" | gw- j- | gwidi

jidi |

Arad tree

Arad tree |

gw- j- | gwaɽe gwɔl(a) elɔ | A tall tree |

| 3."Unit-Collective" | l- ŋw-

li- ŋwu- |

lamɔn

ŋwamɔn livuða ŋwuvuða |

Finger

Fingers Wild fig Wild figs |

l- ŋw-

li- ŋwu- |

lɔiny lɛnɔ

ŋwɔiny ŋwɛnɔ |

That eeg

Those eggs |

| 4."Thing" | g- j-

k- c- |

gödo

jado kivið civið |

Knife

Knives Sword Swords |

g- j-

k- c- |

gilöð gɔla

jilöð jɔla |

A long hoe

Long hoes |

| 5."Harmful Things" | ð- j-

th- c- |

ðimu

jimu thar car |

Scorpion

Scorpions Rope Ropes |

ð- j-

th- c- |

ðuŋo ðɔla

juŋo jɔla |

A long snake

Long snakes |

| 6."Long Things" | ð- d-

th- d- |

ðe

de thole dole |

Arm

Arms Hyena Hyenas |

ð- d-

th- d- |

ðe ði ðɔla

de di dɔla |

My arm is long

My arms are long |

| 7."Diminutives" | ŋ- ny- | ŋimiɽɔ

nyimiɽɔ nirɛ nyirɛ ŋavirɛ yavirɛ |

Cow

Cows Spear Spears Cat Cats |

ŋ- ny- | ŋaɽɛ ŋirithɔ

nyaɽɛ nyirithɔ |

The boy dances

The boys dance |

| 8."Hollow

Deep Things" |

g- n- | giði

niði gömo nomo |

Pot

Pots Cave Caves |

g- n- | giði gigirinu

niði nigirinu |

The pot is broken

The pots are broken |

| 9."Collective"

A "Liquids" B "Abstract Nouns" |

ŋi- (ŋw-)

ŋ- |

ŋan

ŋila ŋəro ŋiɽainy |

Milk (A)

Oil (A) Work (B) Illness (B) |

ŋ- | ŋan ŋadha | Where is the milk |

| 10."Infinitive/Verbal

Noun" |

ði-

ð- |

ðiyo

ðɛliŋa ðiritha |

Drinking

Singing Dancing |

ði-

ð- |

ðiritha ðiŋir | Dancing is pleasant |

| 11."initial Vowel" (miscellaneous

group) |

ji-

j- |

urið

jurið indro jindro |

Gazelle

Gazelles Drum Drums |

y- l- | indro yɛði gwɛlɛ | The chief's drum |

| 12."One Form only" | -

w- b- m- c- j- g- ð- |

öɽu

wuo bur marɔmɔthɔ cu jaba gɛrɛð ðirɔn |

Hair

Help Beam of light gunshot Bowels Chest Butter Wind |

y-

gw- gw- gw- j- j- g- ð- |

Exceptions, outbreaks or further explanation

Noun-class 1

This class encompasses human beings, tribal names and a few animals.[16] The nouns thing, house/home and moon/moth also belong to this category.[18] The prefixes that are mentioned in the chart are predominantly applied as illustrated, with a singular exception: when a noun initiates with ˈmˈ, ˈvˈ or ˈgwˈ only the plural prefixes are employed, omitting the singular prefixes.[16]

Example: friend in Kwara mað(singular) limað(plural)[19]

The subgroup ˈ1aˈ depicts a few personal names, kinship terms and loan-words for occupation or office.[16]

Noun-class 2

This class pertains trees, plants and products of nature. The prefixes in this class do not consistently appear. Certain words allow for the omission of the singular prefix, while others omit the plural prefix, utilizing the singular form as collective.[20]

Some nouns in class 2 use the singular prefix ˈg-ˈ or ˈk-ˈ alongside the plural prefix ˈj-ˈ, similar to class 4. Despite this resemblance, these nouns are categorised into this class due to the reliance on the concord prefixes ˈgw-ˈ and ˈj-ˈ.[21]

For example the doleib palm: gidɛ(Singular) jidɛ(plural)[20]

concord prefix example: A tall doleib palm gidɛ gwɔl(a) elɔ[21]

Noun-class 3

This class depicts things found in sets or large quantities, such as stars, salt, or fruit. Here, the singular form designates a single unit from the set, while the plural form signifies the set as a whole.[21]

Noun-class 4

This class represents commonplace items, utensils, tools, wepons and a subset of “human defects”.[22] Notably, the pattern within this class exhibit inconsistency, with certain words lacking either the singular or plural form.

Example: hunter gina(singular) -

twins - jagul(plural)[22]

Noun-class 5

This class predominantly consists of large or potentially harmful animals, reptiles etc. and it is comparatively smaller in size than other noun-classes. There has been an interchange of terms between Class 5 and Class 6, with words such as ˈroof poleˈ, ˈhairˈ, and ˈropeˈ moving from Class 6 to this classification. Additionally, ˈgiraffeˈ exhibits flexibility, allowing for the application of plural prefixes from both this class and Class 6.

Example: giraffe thul(singular) cul/dul(plural)[23]

Noun-class 6

This class is characterised by items characterised by their great length, such as ˈarmˈ, ˈroadˈ or ˈstickˈ.[23] Plural forms are predominantly formed as shown in the chart. There are only two exceptions within this classification. ˈWindˈ and ˈdry seasonˈ lack a plural form.[24] Additionally, language names usually placed in this class, according to Stevenson, and commonly start with the prefix ˈ-ðˈ.[25]

Example: an Arab gwujulu

Arabic ðijulu[24]

Noun-class 7

This class comprises terms denoting ˈmaleˈ and ˈfemaleˈ, along with domestic or small animals and a variety of miscellaneous nouns. Furthermore, there are no diminutives formed from nouns in other classes, instead Otoro utilizes the adjective for ˈsmallˈ which is '-iti/-ɔga', to convey such meanings.[25]

Noun-class 8

This class represents entities linked by the concepts of hollowness and depth. Some words within this class are in a transitional state, potentially adopting the plural prefix ˈj-ˈ associated with Class 4.

Examples: spoon gaboɽɛ(singular) naboɽɛ/jaboɽɛ(plural)

wing gəbo(singular) jəbo(plural)[26]

Noun-class 9

This class contains collectives of liquids or abstract nouns, often derived from nominal or adjectival roots. Additionally, there are nouns originating from verbal roots, which exhibit the class 10 prefix 'ð-'.[27]

Noun-class 10

This class is made up of nouns in the infinitive as well as verbal nouns utilizing the prefix within this class for the creation of deverbative nouns. Infinitives, primarily ending in the back vowels 'a,' 'o,' or 'ɔ,' are put into this class due to their construction from nominal formations which necessitates concords with qualificatives akin to other nouns.

Example: looking ðimama(noun) manu(verb root)[28]

Noun-class 11

This class comprises nouns with an initial v[29] owel that exhibit a plural form. It is a miscellaneous group with no specific thematic connection like most of other classes. In addition to the discernible prefix pattern, another consistent feature is the transformation of an initial vowel into ˈiˈ after the ˈj-ˈ prefix.[28]

Example: grindstone ɛlɛ(singular) jilɛ(plural)[30]

day anyɛn(singular) jinyɛn(plural)[28]

Noun-class 12

Class 12 encompasses nouns with singular forms, primarily representing collectives or abstract concepts. These nouns exhibit consonants such as 'b,' 'c,' or 'g,' or initiate with vowels, akin to class 11, but notably lack a plural form. Various patterns emerge within this diverse class nouns commencing with initial vowels necessitate the 'y-' prefix as a concord prefix, those starting in 'm,' 'b,' and 'w' demand 'gw-' as concord prefix, and those noun that take 'c' require 'j-' as their concord prefix. These distinct patterns are detailed in the chart above.[30]

“Anomalous Forms”[29]

Despite the presence of various patterns and exception within the noun-classes, certain nouns defy the categorization based on the grouping above. These outliers exhibit irregularities in their prefixes, exemplified by the presence of 'mixed' prefixes.

Example: tooth liŋað Noun-class three, prefix 'l-'

Jiŋað Noun-class four, prefix 'j-'

she goat ŋuɽɔ Noun-class seven, prefix 'ŋ-'

juɽɔ Noun-class four, prefix ' j-'[29]

General observations of the nouns in the Kwara variety

Differentiation in sex

While a few words inherently denote gender distinctions, such as 'ŋidhiri' (bull) and 'ŋimiɽɔ' (cow), the majority of terms, particularly kinship terms, are gender-neutral. For instance English distinctions between 'brother' and 'sister' are represented in a single term in Otoro, namely 'mɛgɛn'. In case where the gender is necessary, the word for female ('gwa') or male ('gwömio') is written after the noun. This addition is introduced by the relative pronoun '-ɛ' and the verb '-irɔ' (to be) with concord prefixes.

Example: male dog ŋin ŋɛ ŋirɔ gwömio (lit. Dog which is male)[31]

Differentiation in size

To express variations in size, the Otoro language relies on adjectival stems. Notably, '-iboðɔ' signifies large size , while '-iti/-ɔga' conveys youth or small size. These adjectival stems are applied with the corresponding concord prefix associated with the noun.

Example: big lion lima loboðɔ

lion cub lima lɛ liti[32]

Compound phrases

This language abstains from employing juxtaposition, yet one can identify a limited number of compound phases to "denote a single idea".[33] To form the compound phrase the language utilizes the genitive particles '-a' and '-ɛði'.

Example: food ŋidi ŋɛði itha (lit. things of eating)

flame ðiŋila ðɛði igo (lit. tongue of fire)[33]

Agent

In the absence of a dedicated term for a particular concept, expressing the agent of the action or occupation involves the use of a relative construction. For example, consider the word 'tree-cutter', which is expressed in Otoro through its literal meaning as 'person who fells trees'. In the Otoro language it will be pronounced as 'gwiji kwɛ gwathipi jaɽɛ'.[33]

Nouns with multiple interpretations

There are instances where words encompass an additional meaning, such as 'göni', which may signify both 'ear' or 'leaf', or the term 'lalia', which holds meanings for 'bees' or 'honey'.[33]

Accusative or Object suffixes

The noun-suffix is used for constructing the object of a dative or transitive verb.[33] However, the functionality of the accusative case or object suffix extends beyond this role. Furthermore it can be employed to describe attributes,[34] indicating adverbial manner, and forming nouns governed by postposition that specifically do not require a concord. Important to know is that the accusative is not utilized with prepositional phrases or the verb 'to be'.[35] With the exception of these cases, no other case-endings are utilized.[33]

In Otoro, the majority of nouns, excluding those in noun-class 1a and tribal names, language names and a few others, typically require a vowel suffix.[33][36] In contrast, tribal names, etc., take consonant suffixes, while some nouns remain in their nominative form without any suffixes. To create the accusative or object form for nouns ending in vowels, which necessitate a suffix, either append them to the nominative form or alter the final vowel.[33] In general, the suffix added to the noun remains mostly consistent between singular and plural forms.[36]

| Consonant suffixes | Vowel suffixes |

|---|---|

| -ŋ, -ŋɛ,- ŋu, -nya, -nyo; -ŋajiɛ (pl.) | -ɛ, -a, -ia, -o, -ɔ, -io |

| Nominative | Accusative | |

|---|---|---|

| Otoro (pl.) | Litoɽo | litoɽaŋɛ[36] |

| Bull | ŋidiri | ŋidhirio[37] |

| Fathers | babaŋa | babaŋaijɛ[36] |

Example of a word which doesn’t take a suffix is 'gwuðɛ' meaning 'gazelle' or 'ŋaɽɛ' with the translation 'boy'.[37]

Example of the different functions:

-Object of transitive or dative verbs

Call your father orniðɔ babaŋa gwua[34]

-Describing an attribute

This man has a long beard gwiji kwɛnɔ guboðɔ lɔija (lit. large as to beard)

-Adverbial matter

He is telling a lie ŋumöðɔ nəviɽagala (lit. speaking by lying)

-Noun governed by postposition

Come near the house ila duno githɔ[35]

The Noun-classes in the different varieties

The Noun-class system remains consistent across all three major dialects. This includes the accusative endings and other features concerning nouns, despite minor distinctions in the Kwijur and Orombe variety. While the vowel suffixes exhibit nearly identical patterns in all three dialects, variations arise in the consonant suffixes. For instance, the vowel ending '-o' in the Kwara variety transforms to '-a' in the Kwijur variety, and the plural ending '-ŋaijɛ' in the Kwara dialect appears as '-anji' in Kwijur and '-aijɛ' in Orombe. Moreover, certain nouns in the Kwara variety requiring the suffix '-ŋɛ' adopt different suffixes or none at all in the other two dialects. In a very few cases, the 'a' or 'o' in '-nya' and '-nyo' may be omitted.[38] However a consistent feature across all three dialects involves nouns remaining in the nominative form, thereby do not require any suffix.[39]

The prefixes utilized in the Kwara variety showcase a similar structure in the Kwijur and Orombe variety, therefore demonstrating a high degree of similarity. In Kwijur, a notable deviation in the first Noun-class regarding to the singular prefix where the 'g' in 'gw-' often undergoes elision, resulting in many nouns initiating with the singular prefix 'w-'. Despite this alteration, the concord prefixes remain consistent and continues to be 'gw-'. This pattern is mirrored in the Orombe variety of Kwijur, albeit to a lesser extent. Additionally, in both dialects the plural prefix is noted to transition from 'l-/li-' to 'j-/c-' in certain cases.[40]

Further changes emerge as some nouns classified in noun-class 4 for the Kwara and Orombe variety are assumed a place in class 8 in the Kwijur variety.[41] Conversely, certain words designated as class 8 in Kwara and Orombe are reclassified in Kwijur as noun in class 4.

The general observation of the nouns regarding sex, size, compound phrases, agents etc. in Kwara have Identical patterns across all three dialects.[42]

| English | Kwijur

sing. |

Kwijur

pl. |

Orombe

sing. |

Orombe

pl. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noun-class 1 | chief

person |

gwelɛny

wiji |

lelɛny

liji |

wɛleny

gwuji |

lɛleny

liji |

| Noun-class 2 | ardeib tree | gwuɽa | juɽa | gwaɽɛ | jaɽɛ |

| Noun-class 3 | finger | lamɔn | ŋwamɔn | lamon | ŋwamon |

| Noun-class 4 | knife

spoon |

gönda

gabiɽɛ |

jönda

jabiɽɛ |

göda

gabuɽɛ |

jöda

jabuɽɛ |

| Noun-class 5 | scorpion | ðimu | jimu | ðimu | jimu |

| Noun-class 6 | tongue | ðiŋila | diŋila | ðiŋila | diŋila |

| Noun-class 7 | cow | ŋimiɽɔ | nyimiɽɔ | ŋimiɽɔ | nyimiɽɔ |

| Noun-class 8 | pot | giði | niði | giði | niði |

| Noun-class 9 | milk

illness |

ŋau (A)

ŋiɽainy (B) |

- | ŋau (A()

ŋiɽainy (B) |

- |

| Noun-class 10 | to sing | ðɛliŋa | - | ðɛliŋa | - |

| Noun-class 11 | drum | indrö | jinfdrö | indrö | jindrö |

| Noun-class 12 | bamboo | amɛn | - | amɛn | - |

Time and "Tense"[44]

Otoro does not distinguish in present, past or future when it comes to “tenses”, instead the language differentiates widely spoken with “aspect”. However, the 'three stems' that exist do not certainly assign to a particular aspect, such as definite, indefinite and dependent. The pattern of time in Otoro appears to be not thoroughly investigated. Consequently, the stems are identified by number rather than being associated with specific aspects.[44]

The three stems are constructed by altering the final vowel of the verb, nevertheless there is no consistent pattern that applies identically to all the verbs. Some verbs may exhibit merely two different final vowels or even just one instead of three. The pattern of the third stem is relatively consistent with the vowel endings '-ɔ' or '-a'. Conversely, the other two stems lack continuity and do not demonstrate as clear a pattern. As a result, the vowel suffixes can be any vowel in the language. Despite the considerable variation in final vowels across all stems, there is a common pattern observed in the majority of verbs, as illustrated by the word 'beat' below.[45]

| 'sleep' | 'cook' | 'beat' | 'drink' | 'bring' | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st stem | dhirɔ | manu | piði | yu | apa |

| 2nd stem | dhirɛ | mani | pi | yu | apa |

| 3rd stem | dhira | mana | piða | yo | apa |

Bibliography

- Kodi, Musa, et al. 2002. Otoro Alphabet Story Book. Sudan: Sudan Workshop Programme.

References

- ↑ Otoro at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Otoro". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/otor1240.

- ↑ Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, Charles D. Fennig. "Ethnologue". https://www.ethnologue.com/language/otr/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Stevenson, Ronald C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 117. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 118. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 143. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tiea and Otoro. Colonge: Köppe. pp. 122. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 127. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 131. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 137. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 138. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 139. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 141. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 142. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. cologne: Köppe. pp. 119. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. cologne: Köppe. pp. 145. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. cologne: Köppe. pp. 145–161. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 147. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 146. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Köppe: Köppe. pp. 148. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 149. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 151. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. ologne: Köppe. pp. 153. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 154. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 155. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 156. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 157. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 159. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 161. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 160. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 163. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 164. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 165. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 170. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 171. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 166. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 169. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 176. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Strevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 177. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 172. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 173. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 175. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 172–175. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 231. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Colonge: Köppe. pp. 234. ISBN 9783896451736.

- ↑ Stevenson, Roland C. (2009). Tira and Otoro. Cologne: Köppe. pp. 232, 234, 236. ISBN 9783896451736.

|