Social:Talodi–Heiban languages

| Talodi–Heiban | |

|---|---|

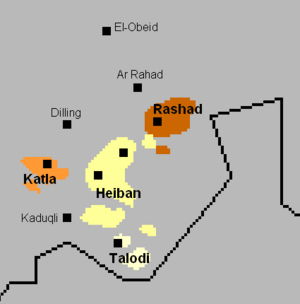

| Geographic distribution | Nuba Hills, Sudan |

| Linguistic classification | Niger–Congo

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | None narr1279 (Talodi)[1] heib1242 (Heiban)[2] |

| |

The Talodi–Heiban languages are a proposed branch of the hypothetical Niger–Congo family, spoken in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. The Talodi and Heiban languages are thought to be distantly related by Dimmendaal,[3] though Glottolog 4.4 does not accept the unity of Talodi–Heiban pending further evidence.[4]

Classification

Roger Blench (2016) notes that the Talodi and Heiban branches share many typological similarities, but few lexical similarities. Blench (2016) considers Talodi and Heiban to each be separate, independent Niger-Congo branches that had later converged due to mutual contact.

Talodi and Heiban had each constituted a group of the Kordofanian branch of Niger–Congo that was posited by Joseph Greenberg (1963); Talodi has also been called Talodi–Masakin, and Heiban has also been called Koalib or Koalib–Moro. Roger Blench notes that the Talodi and Heiban families have the noun-class systems characteristic of the Atlantic–Congo core of Niger–Congo, but that the Katla languages (another putative branch of Kordofanian) have no trace of ever having had such a system, whereas the Kadu languages and some of the Rashad languages appear to have acquired noun classes as part of a Sprachbund, rather than having inherited them. He concludes that the Kordofanian languages do not form a genealogical group, but that Talodi–Heiban is core Niger–Congo, whereas Katla and Rashad form a peripheral branch (or perhaps branches) along the lines of Mande. The Kadu languages may be Nilo-Saharan.

Talodi–Heiban

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- † = extinct

Lafofa (Tegem), sometimes classified as a divergent Talodi language, has a different set of cognates with other Niger–Congo and has been placed in its own branch of Niger–Congo.

Norton & Alaki (2015)

Norton & Alaki (2015: 76, 126)[5] classify the Talodi languages as follows. Proto-Talodi, Proto-Lumun-Torona, and Proto-Narrow Talodi have also been reconstructed by Norton & Alaki (2015).

| Talodi |

| ||||||||||||||||||

Relationship

Lexical correspondences between Proto-Heiban and Proto-Talodi according to Blench (2016):[6]

| Gloss | Proto-Heiban | Proto-Talodi |

|---|---|---|

| belly | *k-aaRi / ɲ- | *C-a[a]rәk / kә- |

| dry | *Ø-undu / k- | *Øandu[k] / t~k |

| ear | *k-ɛɛni / ɲ- | *k-ɛ[ɛ]nu / Ø- |

| fire | *iiga | *t̪-ɪ[ɪ]k / ḷ- |

| give | *N-d̪ɛ-d̪í | *N-d̪í |

| guts | *t̪-y / n̪-u | *t-u[u]k / n- |

| hear | *g-aani / n- | *g-eenu / w- |

| hole | *li-buŋul / ŋu- | *t-ʊbʊ / n- |

| horn | *l-uuba / ŋ- | *t~C-uubʊk / n~m- |

| left side | *t̪-agur | *Ø-ʊgʊlɛ / C- |

| name | *C-iriɲ | *k-әḷәŋaŋ / N~Ø- |

| pull | *uud̪i | *aadu |

| red | *k-ʊʊrɪ | *ɔɔɽɛ |

| rope | *d̪-aar / ŋw- | *t̪-ɔ[ɔ]ḷәk / ḷ- |

| small | *-itti(ɲ) | *ɔt̪t̪ɛ(ŋ) |

| star | *l-ʊrʊm / ŋ- | *C-ɔ[ɔ]d̪ɔt̪ / m |

| stone | *k-adɔl / y- | *p-әd̪ɔk / m |

| tongue | *d̪-iŋgәla / r- | *t̪-ʊlәŋɛ / ḷ- |

| tooth | *l-iŋgat / y- | *C-әɲi[t] / k- |

| wing | *k-ibɔ / ʧ- | *k-ʊbɪ / Ø- |

Noun class prefix comparison between Proto-Heiban and Proto-Talodi according to Blench (2016):[6]

| Noun class | Proto-Heiban | Proto-Talodi |

|---|---|---|

| Persons | *kʷ,gʷ-/l- | *p,b-/Ø- |

| Trees and plants | *k,g/y- | *p-/k- |

| Round things, vital body parts | *li-/ŋʷ- | *ʧ-/m- |

| Symmetrical body parts | *l-/j- | *ʧ-/k- |

| Long thin objects, bushy objects | *ð-/r- | *t/n |

| Small objects, animals | *ŋ-, t-/ɲ- | *ŋ-/ɲ- |

| Liquids | *ŋ- | *ŋ- |

| Uncountables, [dust, grass] | *k- | *t- |

See also

- Heiban Nuba people

- Talodi people

- List of Proto-Talodi reconstructions (Wiktionary)

- List of Proto-Heiban reconstructions (Wiktionary)

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Narrow Talodi". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/narr1279.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Heibanic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/heib1242.

- ↑ Gerrit Dimmendaal, 2008. "Language Ecology and Linguistic Diversity on the African Continent", Language and Linguistics Compass 2/5:842.

- ↑ Güldemann, Tom (2018). "Historical linguistics and genealogical language classification in Africa". in Güldemann, Tom. The Languages and Linguistics of Africa. The World of Linguistics series. 11. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 58–444. doi:10.1515/9783110421668-002. ISBN 978-3-11-042606-9.

- ↑ Norton, Russell, and Thomas Kuku Alaki. 2015. The Talodi Languages: A Comparative-Historical Analysis. Occasional papers in the study of Sudanese languages 11:31-161.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Blench, Roger. 2016. Do Heiban and Talodi form a genetic group and how are they related to Niger-Congo?.

- Roger Blench. Unpublished. Kordofanian and Niger–Congo: new and revised lexical evidence.

- Roger Blench, 2011, Should Kordofanian be split up?, Nuba Hills Conference, Leiden

- Blench, Roger. 2016. Do Heiban and Talodi form a genetic group and how are they related to Niger-Congo?.

|