Social:Nezak Huns

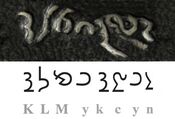

Nezak Huns 𐭭𐭩𐭰𐭪𐭩 nycky | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 484–665 CE | |||||||||||||

| Template:Continental Asia in 500 CE The Nezak Huns and contemporary continental Asian polities c. 500 CE. | |||||||||||||

| Capital | Ghazna Kapisa | ||||||||||||

| Common languages | Pahlavi script (written)[1] Middle Persian (common)[1] | ||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism Hinduism | ||||||||||||

| Government | Nomadic empire | ||||||||||||

| Nezak Shah | |||||||||||||

• 653 - 665 | Ghar-ilchi | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Late Antiquity | ||||||||||||

• Established | 484 | ||||||||||||

• Disestablished | 665 CE | ||||||||||||

| Currency | Hunnic Drachm | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Today part of | Afghanistan Pakistan | ||||||||||||

The Nezak Huns (Pahlavi: 𐭭𐭩𐭰𐭪𐭩 nycky), also Nezak Shahs,[1] was a significant principality in the south of the Hindu Kush region of South Asia from circa 484 to 665 CE. Despite being traditionally identified as the last of the Hunnic states, their ethnicity remains disputed and speculative. The dynasty is primarily evidenced by coinage inscribing a characteristic water-buffalo-head crown and an eponymous legend.

The Nezak Huns rose to power after the Sasanian Empire's defeat by the Hephthalites. Their founder may have been a Huna ally or an indigenous ruler who had accepted tributary status. Little is known about the intermediary rulers; they received regular diplomatic missions from the Tang dynasty, and some coexisted with the Alchon Huns from about the mid-sixth century. The polity collapsed in the mid-seventh century after experiencing increasingly frequent invasions from the Arab frontier. A vassal usurped the throne and established the Turk Shahis.

Etymology

In contemporary sources, the word "Nezak" appears either as the Arabic nīzak or the Pahlavi nyčky.[2] The former was used only to describe the Nezak Tarkhans — rulers in Western Tokharistan — while the latter was used in the coinage of the Nezak Huns.[2] The etymology remains disputed; Frantz Grenet sees a possible — yet not firmly established — connection with Middle Persian nēzag ("spear") while János Harmatta traces back to the unattested Saka *näjsuka- "fighter, warrior" from *näjs- "to fight".[2][3]

The Middle Chinese words Nasai (捺塞) and Nishu (泥孰) have also been proposed as probable transcriptions of Nezak, but these have phonetic dissimilarities.[4] Nonetheless, from a review of Chinese chronicles, Minoru Inaba, a historian of medieval Central Asia at Kyoto University, concludes Nishu to have been both a personal name and titular epithet across multiple Turkic tribes.[5]

Territory

The Nezak Huns ruled over the State of Jibin, mostly referred to as Kapisi — formerly Cao —[6][lower-alpha 1] by contemporaneous Buddhist pilgrims.[8] Kapisi composed eleven vassal-principalities during Xuanzang's visit in c. 630, including Lampā, Varṇu, Nagarahāra, and Gandhara; Taxila had been only recently lost to Kashmir.[9][10]

Sources

Literature

Pilgrim Travelogues

The earliest mention of Kapisi is from Jñānagupta, a Buddhist pilgrim; he stayed there in 554 CE while travelling to Tokharistan.[11] Dharmagupta, a South-Indian Buddhist monk, would visit the polity in the early seventh century, but his biography by Yan Cong is not extant.[12]

Xuanzang, a Chinese Buddhist monk who visited Kapisi in about 630, provides the most detailed description of the Nezaks, even though he never mentions the name of the ruling dynasty. Xuanzang met the king in Udabhandapura and then traveled with him to Ghazni and Kabul.[7] The king is described as a fierce and intelligent warrior, belonging to the shali (刹利) / suli (窣利) race — Kshatriyas (?) —[lower-alpha 2] and commanding rude subjects.[13]

Chinese Histories

The Cefu Yuangui — an 11th-century Chinese encyclopedia — and Old Book of Tang — a 10th-century Chinese history — record thirteen missions from Jibin to the Tang Court from 619 to 665;[lower-alpha 3] while neither of them, like Xuanzang, mentions the name of the ruling dynasty, historians assume a reference to the Nezaks.[11][14] The most-comprehensive listing among them, dating from 658, is the record of the thirteenth mission, which declared Jibin as the "Xiuxian Area Command" and gave an account of a local dynasty of twelve rulers starting from Xinnie and ending with Hexiezi:[15]

In the third year of the Xianqing reign [658 CE], when [Tang envoys] investigated the customs of this state [Jibin], people said: "From Xinnie, the founder of the royal house, up to the present [King] Hexiezi, the throne has been passed from father to son, [and by now] there have been twelve generations." In the same year, the city was established as Xiuxian Area Command.

The names of the ten intermediary rulers remain unknown — Waleed Ziad, a historian of Islam and numismatist specializing in South Asia, however, cautions the reference to twelve generations was probably not intended in the literal sense.[18][19] The last mention of the dynasty is in 661 when the chronicles record the king of Jibin received a formal investiture from the Chinese court as Military Administrator and Commander-in-Chief of Xiuxian Area and eleven prefectures.[16][17][lower-alpha 4]

Various compilations of the Tang dynasty would continue to mention the erstwhile Kings of Jibin, emphasizing that they wore a bull-head crown.[20][lower-alpha 5] This invocation of the crown allows historians to link the Kingdom of Jibin with the Nezak Huns whose coinage features the same motif.[23]

Coinage

Phase I

The Nezaks started to mint their coins on the model of Sasanian coinage but incorporated Alkhon iconography alongside their distinctive styles.[24] The result was unique, as Xuanzang noted.[23] There were four types of drachms and obols in circulation.[24] Coins exhibit progressive debasement as silver decrease in favour of alloys incorporating increasing quantities of copper.[18]

The obverse depicts a male bust occupying the centre; the facial profile varies.[25] The figure always adorns a symmetrically winged crown — derived from Sasanian ruler Peroz I's third phase of mints (c. 474 – c. 484) under Hephthalite captivity —[lower-alpha 6] which is supplemented on top with a water buffalo-head;[24][lower-alpha 7] this "buffalo-crown" became the defining characteristic of the Nezaks.[26][lower-alpha 8] A wing-shaped vegetal appendage, borrowed from Alchon coinage, is found just beneath the bust.[29] The figure also wears a necklace with two flying ribbons of slightly varying shapes and an earring with two beads;[30] some samples include a Brahmi akshara of uncertain significance beneath the ribbons.[31] Circumscribed on the right is a Pahlavi legend meaning "King of the Nezak", which leads to the dynastic nomenclature.[1][lower-alpha 9] An "ā" (𐭠) or a "š" (𐭮), perhaps corresponding to the mints of Ghazni and Kabul, follows.[32][lower-alpha 10]

On the reverse, the Sasanian-type, consisting of the lit Zoroastrian fire-altar with two attendants carrying barsom bundles,[lower-alpha 11] was adopted, but unique "sun-wheels" were added above their heads.[33] The flame shape widely varies between a triangle, feather and bush.[34] Two Brahmi aksharas are occasionally present.[35]

Phase II: Alchon-Nezak crossovers and derivatives

Hoards containing Alchon overstrikes against Nezak flans by Toramana II have been discovered around Kabul.[39][40] Further, a class of drachms and unprecedented coppers — termed the Alchon-Nezak crossover — have Nezak busts adorned in Alchon-styled crescent crowns alongside a contracted version of the Pahlavi legend and the Alchon tamgha (![]() ) on the obverse.[41][42]

) on the obverse.[41][42]

These crossovers evolved into a series in which a new legend (Śri Sāhi), either in Bactrian or Brahmi, replaces the Pahlavi legend.[43][lower-alpha 12] Finds from around the Sakra region — a sacred complex in ancient Gandhara —[lower-alpha 13] feature votive coins of these two kinds as well as derivatives where the structures on the reverse and the Alchon tamgha lose their meaning and degenerate into geometrical motifs but the design of the Nezak-inspired bust remains largely conserved.[46] Whether these coins were issued by the later Nezaks or the early Turk Shahis remains debated.[47][lower-alpha 14]

History

Origins and establishment

The Nezaks were the last of the four "Hunic" states known collectively as Xionites or "Hunas", their predecessors being, in chronological order; the Kidarites, the Hephthalites, and the Alchons.[48][lower-alpha 15] They took control of Zabulistan after the defeat and eventual death of Sassanian Emperor Peroz I (r. 459–484) by the Hephthalites.[23][26] Their capital was at modern-day Bagram.[49]

The name of their founder was only recorded by the Chinese chronicles of the thirteenth diplomatic mission (658) as Xinnie — which has since been reconstructed as "Khingal" — who may have been identical with Khingila (430-495) of the Alchon Huns.[18] The presence of Nezak bull's heads in some Alchon coins minted at Gandhara supports a link between the two groups.[29] However, Shōshin Kuwayama—primarily depending on Xuanzang's recording the rulers of Kapisi as Kshatriya, about two centuries later, and the absence[lower-alpha 16] of Hunnic identifiers in coinage—ascribes an indigenous origin to the dynasty.[50] Klaus Vondrovec, a numismatist specializing in ancient Central Asia, finds his arguments to be unpersuasive.[51] Inaba proposes that the Nezaks were indigenous but being a tributary state of the Hephthalites, had to accept Turkish titles.[52] Ziad and Matthias Pfisterer reject the existence of any means to speculate on the ethnic identity of the Nezaks—Khingila is a very common name in the history of Asia Minor, that was probably a title that commanded respect; and Hindu societies had a history of absorbing foreign warriors within the Kshatriya fold.[53][54]

Overlap with Alchons and Sassanians

Between 528 and 532, the Alchons had to withdraw from mainland India into Kashmir and Gandhara under Mihirakula.[51] Göbl proposed that a few decades later, they had migrated further westward via the Khyber pass into Kabulistan; scholars agree, on the evidence of the Alchon-Nezak crossover mints, this migration did occur and brought them in contact with the Nezaks.[55][lower-alpha 17] Whether the Alchons co-ruled with the Nezaks, submitted to them or nominally subdued them remains speculative.[45]

Around the same time (c. 560), the Sasanian Empire under Khosrow I allied with the Western Turks to defeat the Hepthalites and took control of Bactria. They may also have usurped Zabulistan from the Nezaks, as suggested by the creation of Sasanian coin mints in the area of Kandahar during the reign of Ohrmazd IV (578-590).[56] However, the Alchon-Nezaks (?) appear to have recaptured Zabulistan by the end of the sixth century.[36]

These interactions left little long-lasting influence on the territorial extents of the Nezaks; when Xuanzang visited them in about 630, they were arguably in their prime.[45] In 653, a Tang dynasty diplomatic mission recorded that the crown prince had acceded to the throne of Jibin; scholars assume this prince to be Ghar-ilchi, who five years later would be recorded as the twelfth Nezak ruler in the thirteenth diplomatic mission.[17]

Decline: Rashidun and Umayyad invasions

Lua error in Module:Location_map/multi at line 27: Unable to find the specified location map definition: "Module:Location map/data/Hindu-Kush" does not exist.In 654, an army of around 6,000 Arabs led by Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura of the Rashidun caliphate attacked Zabul and laid seize to Rukhkhaj and Zamindawar, eventually conquering Bost and Zabulistan—while records do not mention the names and dynastic affiliations of the subdued rulers, it is plausible that the Nezaks suffered severe territorial losses.[57] In 661, an unnamed ruler—possibly, Ghar-Ilchi—was confirmed as Governor of Jibin under the newly formed Chinese Anxi Protectorate, and would broker a peace treaty with the Arabs, who were reeling from the First Fitna and lost their gains.[57][58] In 665, Abd al-Rahman ibn Samura occupied Kabul after a months-long siege but was soon ousted; the city was reoccupied after another year-long siege.[lower-alpha 18] The Nezaks were mortally weakened though their ruler—who is not named in sources but might have been Ghar-ilchi—was spared upon converting to Islam.[61]

They were replaced by the Turk Shahis, probably first in Kabul and later throughout the territory.[62] According to Hyecho, a Korean Buddhist monk, who visited the region about 50 years after the events, the first Turk Shahi ruler of Kapisi—named Barha Tegin by Al-Biruni—was a usurper who served as a military commander (or vassal) in the service of the preceding king.[63][64][lower-alpha 19] Xuanzang, returning via Kapisa in 643, had noted Turks[lower-alpha 20] ruling over Vrijsthana/Fulishisatangna—a polity between Kapisi and Gandhara that was likely located in the region of modern-day Kabul—and Barha Tegin might have had belonged to them.[68] Baladhuri notes of the "Kabul Shah" to have purged all Muslims out of Kabul—whether he refers to the city or the region is unclear—in 668, drawing Arab forces into renewed offensive;[69] if the "Kabul Shah" alludes to the last Nezak, the resulting conflict might have provided the ground for the rise of Turk Shahis.[70][71]

According to Kuwayama, the Nezaks probably survived as a local chieftaincy centred in or around the town of Kapisi for a few more decades; archaeological evidence obtained from the excavation of Begram points to a gradual decline.[72]

Religion

During Xuanzang's visit, Buddhism was the dominant religion; the region had over a hundred monasteries—especially around the capital. The ruler commissioned an 18-foot (5.5 m)-high image of the Buddha every year and held an assembly for dispensing alms. Nevertheless, religious pluralism was evident in the hundreds of temples for the "Devas" (Hindu deities) and many "heretical" (non-Buddhist) ascetics.[73][lower-alpha 21] Buddhism declined south of the capital, and monasteries in Gandhara bore a deserted look.[68][75] Xuanzang also alluded to a conflict between two heretic sects—those who worshipped "Zhuna" and those Sun—resulting in the former migrating to neighbouring Zabul.[76][lower-alpha 22]

Link with Nezak Tarkhans

At least two rulers in Western Tokharistan used the appellation "Nezak Tarkhan";[2] like "Shah", "Tarkhan" was a popular title among rulers in Central Asia.[78] One of these Nezak Tarkhans played an essential role in leading a revolt against the Arab commander Qutayba ibn Muslim in around 709 to 710 and was even promised aid by the Turk Shahis.[2][18] Historians have speculated about possible relations with the Nezak Huns.[1]Template:History of Afghanistan

Notes

- ↑ The regions cannot be held to be synonymous for sources post-dating the fall of Nezak Huns. Xuanzang's Kapisi referred to the province centred around then-capital-town Kapisi (modern-day Begram) whereas later sources use the term to denote a territorial expanse including Gandhara or the new capital Kabul.[7]

- ↑ The former term has been extensively used in Buddhist Sutras to mean "Kshatriya". Some manuscripts use the latter, which can either be a corrupted reading or refer to inhabitants of Sogdia.[13]

- ↑ These missions were in the years 619, 629, 637, 640, 642, 647, 648, 651, 652, 653, 654, 658, and 665.

- ↑ For a list of the sixteen prefectures, consult Inaba 2015, p. 108

- ↑ Mentioned to be worn by the King of Cao in the chapter on Western Regions in the Běishǐ (659 CE); repeated in the section on Jibin in the Tongdian (766-776 CE).[21] Both the descriptions were likely borrowed from the chapter on Western Regions in the Suishu (629-630 CE); extant editions, however, replace bull-head with fish-head. This scribal error was also carried into the Cefu Yuangui, edited c. 11th century.[22]

- ↑ Vondrovec and Alram imposed a terminus post quem of about 474 accordingly, which Ziad also accepts.[23][26] Göbl, however, rejected evidence of any link that the wings were prominently attached to the diadem in Nezak coinage, unlike the unclear nature in Peroz's coinage.[27]

- ↑ The animal was a water-buffalo given the ribbed appearance of the horns, not a bull or zebu.[28]

- ↑ Such coins appear well into the 8th century, the design continuing almost unchanged for a period of about 150 years.[18]

- ↑ Some historians misread this legend as "Napki Malka", who was assumed to be a Nezak King. The use of Pahlavi may reflect the importance of Middle Persian as the primary language of their territories at that time rather than origins.[1]

- ↑ Numismatists use this mark to group Nezak coinage into two types; there is a consensus among scholars the latter type started earlier than the former.

- ↑ The long barsom bundles were likely derived from the mints of Yazdegerd II, who preceded Peroz I.[33]

- ↑ Whether these two varieties were contemporaneous remains a matter of speculation.

- ↑ Gandhara was added to Nezak territory only in the aftermath of Alchon desertion.[44] Xuanzang's note that Kapisa wrested control of the territory after the previous dynasty (Alchons - ?) became "extinct" and the unavailability of Phase I mints affirm such a view.[45]

- ↑ Vondrovec accepts Gobl's speculative assignment of the series to Tegin Shah of the succeeding Turk Shahis. In contrast, Ziad rejects the idea the Turk Shahis would have felt a need to reintroduce long-extinct Alchon iconography, and categorizes them as local mints by the Nezaks c. mid-seventh century bearing then-extant Alchon influence.[47]

- ↑ However, there were fair overlaps between these groups.

- ↑ Kuwayama emphasizes on the stylistic differences: there was no neck and the ribbed nature of horns is unclear.

- ↑ This interaction happened under Toramana himself or a Toramana II.

- ↑ Ibn A'tham al-Kufi notes the ruler of Kabul to have mounted periodic resistances against Samura before retreating into the city.[59] This ruler is unfavourably compared to Samura, who had persisted in the siege despite difficulties.[60]

- ↑ From Kashmir I travelled further northwest. After one month's journey across the mountains I arrived at the country of Gandhara. The king and military personnel are all Turks. The natives are Hu people; there are Brahmins. The country was formerly under the influence of the king of Kapisa. A-yeh [alternatively read as "The father", than a personal name, referring to Barha Tegin, father of then-King Tegin Shah}] of the Turkish King took a defeated cavalry [alternatively "led an army and a tribe" or "led troops of his entire tribe"[65]] and allied himself to the king of Kapisa. Later, when the Turkish force was strong, the prince assassinated the king of Kapisa [possibly Ghar-ilchi] and declared himself king. Thereafter, the territory from this country to the north was all ruled by the Turkish king, who also resided in the country.

- ↑ 'Turk" was used rather liberally in Arabic as well as Chinese sources to describe a wide spectrum of alien people. These Turks were distinct from the Northern Turks and might have been a reference to the nomadic Khalaj Turks.[67]

- ↑ From the descriptions provided, Beal interpreted these ascetics as Kāpālikas, Digambara Jains, and Pashupatas. Kuwayama as well as Lorenzen do not object.[73][74]

- ↑ Kuwayama suspects the original shrine of Zhuna to have been at Khair Khaneh before it was occupied by the adherents of Surya, the solar God. Excavations show that the complex had two phases of constructions, and statues of the latter have been recovered only from the later constructions.[77]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Rezakhani 2017, p. 159.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Inaba 2010, p. 191.

- ↑ Grenet 2002, p. 159.

- ↑ Inaba 2010, p. 192.

- ↑ Inaba 2010, pp. 196–197.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 30–32.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ziad 2022, p. 79.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 40, 60.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, p. 49.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, p. 42.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Kuwayama 2000, p. 41.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, p. 47.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Inaba 2010, p. 193.

- ↑ Kuwayama 1991, p. 115.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, p. 164.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Balogh 2020, p. 104.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Rahman 2002a, p. 37.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Alram 2014, pp. 280–281.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, p. 59.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 45––46.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, p. 45.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Ziad 2022, p. 60.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Vondrovec 2010, p. 169.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 48–49, 51–53.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Alram 2014, p. 280.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, p. 171.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Vondrovec 2010, p. 179.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 45, 51.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 52-53.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, pp. 160-162.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Vondrovec 2010, p. 170.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 52–54.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 54.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Alram 2014, p. 282.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Gariboldi 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, pp. 174, 176–177.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, p. 182.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, p. 63.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Ziad 2022, p. 61.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, pp. 64–67, 70–71.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Ziad 2022, pp. 72–74.

- ↑ Rezakhani 2017, p. 158.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 36.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, p. 43.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Vondrovec 2010, p. 174.

- ↑ Inaba 2010, p. 200.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, pp. 44–45.

- ↑ Pfisterer & Uhlir 2015, p. 63.

- ↑ Alram 2014, p. 278.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Morony 2012, p. 216.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, pp. 59, 89.

- ↑ Rehman 1976, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Rehman 1976, pp. 59.

- ↑ Rehman 1976, pp. 59, 64.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Rahman 2002a, pp. 37, 39.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, p. 59.

- ↑ Kuwayama 1993.

- ↑ Ch'o, Ch'ao & Yang 1984, p. 48.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, p. 88.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Ziad 2022, p. 50.

- ↑ Rehman 1976, pp. 64.

- ↑ Ziad 2022, p. 90.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 56-57, 60.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Kuwayama 2000, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Lorenzen 1972, pp. 15–16.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 25–29.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 27–30.

- ↑ Kuwayama 2000, pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Vondrovec 2010, p. 199.

Sources

- Alram, Michael (2014). "From the Sasanians to the Huns New Numismatic Evidence from the Hindu Kush". The Numismatic Chronicle 174: 261–291. (registration required)

- Balogh, Dániel (12 March 2020) (in en). Hunnic Peoples in Central and South Asia: Sources for their Origin and History. Barkhuis. ISBN 978-94-93194-01-4.

- Ch'o, Hye; Ch'ao, Hui; Yang, Han-sŭng (1984) (in en). The Hye Ch'o Diary: Memoir of the Pilgrimage to the Five Regions of India. Jain Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-89581-024-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=pWo47KtISe8C&pg=PA48.

- Gariboldi, Andrea (2004). "Astral Symbology on Iranian Coinage". East and West 54 (1/4): 31–53. ISSN 0012-8376. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29757605.

- Grenet, Frantz (2002). "Nēzak". Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition. https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/nezak.

- Inaba, Minoru (2010). "Nezak in Chinese Sources". Coins, Art and Chronology II: The First Millennium C.E. in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. ISBN 978-3-7001-7027-3. https://www.academia.edu/7838562.

- Inaba, Minoru (2015). "From Caojuzha to Ghazna/Ghaznīn: Early Medieval Chinese and Muslim Descriptions of Eastern Afghanistan". Journal of Asian History 49 (1–2): 109–117. doi:10.13173/jasiahist.49.1-2.0097. ISSN 0021-910X.

- Kuwayama, Shoshin (1991). "The Horizon of Begram III and Beyond A Chronological Interpretation of the Evidence for Monuments in the Kāpiśī-Kabul-Ghazni Region". East and West 41 (1/4): 79–120. ISSN 0012-8376. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29756971.

- Kuwayama, Shōshin (桑山正進) (1993). "6-8 世紀 Kapisi-Kabul-Zabul の貨幣と發行者 (6-8 seiki Kapisi-Kabul-Zabul no kahei to hakkōsha "Coins and Rulers in the 6th-8th Century Kapisi-Kabul-Ghazni Regions, Afghanistan"" (in ja). 東方學報 65: 405 (26). https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/2433/66741/1/jic065_430.pdf.

- Kuwayama, Shoshin (March 2000). "Historical Notes on Kāpiśī and Kābul in the Sixth-Eighth Centuries". ZINBUN 34 (1): 25–77. doi:10.14989/48769. ISSN 0084-5515. https://repository.kulib.kyoto-u.ac.jp/dspace/handle/2433/48769.

- Lorenzen, David N. (1972). The Kāpālikas and Kālāmukhas: Two Lost Śaivite Sects. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-01842-6.

- Morony, Michael G. (16 February 2012). "Iran in the Early Islamic Period". in Daryaee, Touraj (in en). The Oxford Handbook of Iranian History. Oxford University Press, USA. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199732159.013.0009. ISBN 978-0-19-973215-9.

- Pfisterer, Matthias; Uhlir, Katharina (2015). "Coinage of the Nezak Shah: A Perspective from the Hoard Evidence". in McAllister, Patrick (in en). Cultural Flows across the Western Himalaya. Beiträge zur Kultur- und Geistesgeschichte Asiens (BKGA). Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften. pp. 41–104. ISBN 978-3-7001-7585-8. https://austriaca.at/0xc1aa5576%200x0031eae5.pdf.

- Rahman, Abdul (August 2002a). "New Light on the Khingal, Turk and the Hindu Sahis". Ancient Pakistan XV: 37–42. http://journals.uop.edu.pk/papers/AP_v15_37to42.pdf.

- Rehman, Abdur (January 1976). The Last Two Dynasties of the Sahis: An analysis of their history, archaeology, coinage and palaeography (Thesis). Australian National University.

- Rezakhani, Khodadad (2017). "The Nezak and Turk period" in "ReOrienting the Sasanians: East Iran in Late Antiquity". Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1–256. ISBN 978-1-4744-0030-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=bjRWDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA157.

- Vondrovec, Klaus (2010). "Coinage of the Nezak". Coins, Art and Chronology II: The First Millennium C.E. in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. ISBN 978-3-7001-7027-3. https://www.academia.edu/880242.

- Ziad, Waleed (2022). "The Nezak Shahis of Kapisa-Gandhāra". In the Treasure Room of the Sakra King : Votive Coinage from Gandhāran Shrines. ISBN 978-0-89722-737-7.

Further reading

- Payne, Richard (2016). "The Making of Turan: The Fall and Transformation of the Iranian East in Late Antiquity". Journal of Late Antiquity (Johns Hopkins University Press) 9: 4–41. doi:10.1353/jla.2016.0011.

|