Social:Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II

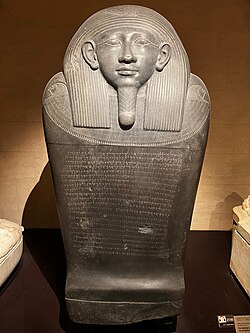

| Eshmunazar II sarcophagus | |

|---|---|

The sarcophagus at the Louvre, 2022 | |

| Material | Amphibolite |

| Long | 2.56 m (8.4 ft) |

| Height | 1.19 m (3.9 ft) |

| Width | 1.25 m (4.1 ft) |

| Writing | Phoenician language |

| Created | 6th-century BC |

| Period/culture | Achaemenid Phoenicia |

| Discovered | 19 January 1855 Magahret Abloun [Cavern of Apollo], Sidon, modern-day Lebanon [ ⚑ ] : 33°33′04″N 35°22′26″E / 33.551°N 35.374°E |

| Discovered by | Alphonse Durighello |

| Present location | The Louvre, Paris |

| Identification | AO 4806 |

| Language | Phoenician |

| Culture | Ancient Egyptian, Phoenician |

The sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis (dubbed by French Semitic philologist and biblical scholar Ernest Renan Nécropole Phénicienne), a hypogeum complex southeast of the city of Sidon in modern-day Lebanon. The sarcophagus was discovered by Alphonse Durighello, a diplomatic agent in Sidon engaged by Aimé Péretié, the chancellor of the French consulate in Beirut. The sarcophagus was sold to Honoré de Luynes, a wealthy French nobleman and scholar, and was subsequently removed to the Louvre after the resolution of a legal dispute over its ownwership. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and another on its trough, under the sarcophagus head. The inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper, the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription after the Karatepe bilingual inscription.

Eshmunazar II (Phoenician: 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 ʾšmnʿzr, r. c. 539 – c. 525 BC) was a Phoenician King of Sidon and the son of King Tabnit. His sarcophagus was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC.

More than a dozen scholars across Europe and the United States rushed to translate the sarcophagus inscriptions after its discovery. French orientalist Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès noted the similarities between the Phoenician language and Hebrew. The translation allowed scholars to identify the king buried inside, his lineage, and his construction feats. The inscription warns against disturbing Eshmunazar II's place of repose; it also recounts that the "Lord of Kings", the Achaemenid king, granted Eshmunazar II the territories of Dor, Joppa, and Dagon in recognition for his services.

The discovery led to great enthusiasm for archaeological research in the region, and was the primary reason for Renan's 1860-61 Mission de Phénicie, the first major archaeological mission to Lebanon and Syria.

Eshmunazar II

Eshmunazar II (Phoenician:𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 ʾšmnʿzr, a theophoric name meaning 'Eshmun helps')[1][2] was the Phoenician King of Sidon , reigning c. 539 BC to c. 525 BC.[3] He was the grandson of King Eshmunazar I and a vassal king of the Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar II succeeded his father, Tabnit I, on the throne of Sidon. Tabnit I, ruled briefly before his death, and his sister-wife, Amoashtart, acted as an interregnum regent until the birth of Eshmunazar II. Amoashtart then ruled as Eshmunazar II's regent until he reached adulthood. Eshmunazar II, however, died at the premature age of 14 during the reign of Cambyses II of Achaemenid Persia, and was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.[4][5][6] Eshmunazar II, like his mother,[7] father and grandfather, was a priest of Astarte.[8][9] Temple building and religious activities were important for the Sidonian kings to demonstrate their piety and political power. Eshmunazar II and his mother, Queen Amoashtart, constructed new temples and religious buildings dedicated to Phoenician gods such as Baal, Astarte, and Eshmun.[9][10]

History

Phoenician funerary practices

The Phoenicians emerged as a distinct culture on the Levantine coast in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550 – c. 1200 BC) as one of the successor cultures to the Canaanites.[11][12] They were organized into independent city-states that shared a common language, culture, and religious practices. They had, however, diverse mortuary practices, including inhumation and cremation.[13]

Archaeological evidence of elite Achaemenid period burials abounds in the hinterland of Sidon. These include inhumations in underground vaults, rock-cut niches, and shaft and chamber tombs in Sarepta,[14] Ain al-Hilweh,[15] Ayaa,[16][17] Mgharet Abloun,[18] and the Temple of Eshmun.[19] Elite Phoenician burials were characterized by the use of sarcophagi, and a consistent emphasis on the integrity of the tomb.[20][21] Surviving mortuary inscriptions from that period invoke deities to assist with the procurement of blessings, and to conjure curses and calamities on whoever desecrated the tomb.[22]

The first record of the discovery of an ancient necropolis in Sidon was made in 1816 by English explorer and Egyptologist William John Bankes.[23][24][note 1]

Modern discovery

The sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II was discovered on 19 January 1855[25][note 2] by the workmen of Alphonse Durighello, an agent of the French consulate in Sidon hired by Aimé Péretié, an amateur archaeologist and the chancellor of the French consulate in Beirut.[28][29][30] Durighello's men were digging in the grounds of an ancient necropolis (dubbed by French Semitic philologist and biblical scholar Ernest Renan Nécropole Phénicienne) in the plains southeast of the city of Sidon. The sarcophagus was found outside a hollowed-out rocky mound that was known to locals as Magharet Abloun (The Cavern of Apollo).[28][29] It was protected by a vault, of which some stones still remained in place. One tooth, a piece of bone, and a human jaw were found in the rubble during the sarcophagus extraction.[28]

Cornelius Van Alen Van Dyck, an American missionary physician, made it to the scene and made a transcript of the inscription which was first published on 11 February 1855 in The Journal of Commerce.[31][32]

On 20 February 1855, Durighello informed Péretié of the find.[28][29][30] Durighello had taken advantage of the absence of laws governing archaeological excavation and the disposition of the finds under the Ottoman rule over Lebanon, and had been involved in the lucrative business of trafficking archaeological artifacts. Under the Ottomans, it sufficed to either own the land or to have the owner's permission to excavate. Any finds resulting from digs became the property of the finder.[33] To excavate, Durighello had bought the exclusive right from the land owner, the then Mufti of Sidon Mustapha Effendi.[28][33][34]

Ownership dispute

Durighello's ownership of the sarcophagus was contested by the British vice-consul general in Syria, Habib Abela.[35][36] The matter quickly took a political turn; in a letter dated 21 April 1855 the director of the French national museums, Count Émilien de Nieuwerkerke requested the intervention of Édouard Thouvenel, the French Ambassador to the Ottomans, stating that "It is in the best interest of the museum to possess the sarcophagus as it adds a new value at a time in which we start studying with great zeal Oriental antiquities, until now unknown in most of Europe."[36] A commission was appointed by the Governor of the Sidon Eyalet, Wamik Pasha to look into the case, and, according to the minutes of the meeting dated 24 April 1855, the dispute resolution was transferred to a commission of European residents that unanimously voted in favor of Durighello.[33][37][38][39]

The Journal of Commerce reported on the issue of the legal dispute:

In the meantime, a controversy has arisen in regard to the ownership of the discovered monument, between the English and French Consuls in this place - one having made a contract with the owner of the land, by which he was entitled to whatever he should discover in it; and the other having engaged an Arab to dig for him, who came upon the sarcophagus in the other consul's limits, or , as the Californians would say, within his "claim".[37]

Péretié purchased the sarcophagus from Durighello and sold it to wealthy French nobleman and scholar Honoré de Luynes for £400. De Luynes donated the sarcophagus to the French government to be exhibited in the Louvre.[33][40][41]

Removal to the Louvre

Péretié rushed the sarcophagus' laborious transportation to France. The bureaucratic task of removing the sarcophagus to France was facilitated with the intervention of Ferdinand de Lesseps, then consul-general of France in Alexandria, and the French Minister of Education and Religious Affairs, Hippolyte Fortoul. During the transportation to the Sidon port, the citizens and the governor of Sidon gathered, escorted, and applauded the convoy; they adorned the sarcophagus with flowers and palm branches while 20 oxen, assisted by French sailors, dragged the carriage to the port.[42] At the wharf, the crew of the French navy corvette La Sérieuse boarded the sarcophagus' trough, and then its lid onto a barge, before lifting it to the military corvette. The corvette commander, Delmas De La Perugia read an early translation of the inscriptions, explaining the scientific importance and historical significance of the cargo to his crew.[42][43]

The sarcophagus of King Eshmunazar II is housed in the Louvre's Near Eastern antiquities section in room 311 of the Sully wing. It was given the museum identification number of AO 4806.[29]

- Maps from Renan's 1864 Mission de Phénicie

Description

The Egyptian anthropoid-style sarcophagus dates to the 6th-century BC,[44] it is made of a solid, well polished block of bluish-black amphibolite.[45][41] It measures 256 cm (8.40 ft) long, 125 cm (4.10 ft) wide, and 119 cm (3.90 ft) high.[note 3][29]

The lid displays a relief carving of the figure of a deceased person in the style of the Egyptian mummy sarcophagi.[41] The effigy of the deceased is portrayed smiling,[37] wrapped up to the neck in a thick shroud, leaving the head uncovered. The effigy is dressed with a large Nubian wig, a false braided beard, and a Usekh collar ending with falcon heads at each of its extremities, as is often seen at the neck of Egyptian mummies.[29][28][37]

Two other sarcophagi of the same style were also unearthed in the necropolis.[46]

Inscriptions

The Egyptian-style sarcophagus was free from hieroglyphs; however, it has 22 lines of 40 to 55 letters each of Phoenician text on its lid.[28][47] The lid inscriptions occupy a square situated under the sarcophagus' Usekh collar and measure 84 cm (2.76 ft) in length and width.[38][41] A second inscription, carved more delicately and uniformly , was found around the head curvature on the trough of the sarcophagus. It measures 140 cm (4.6 ft) in length and consists of six lines and a fragment of a seventh line.[38][48][49] As is customary for Phoenician writing, all the characters are written without spaces separating each word, except for a space in line 13 of the lid inscription, which divides the text into two equal parts.[49] The lid letters are not evenly spaced, ranging from no distance to a spacing of 6.35 mm (0.250 in). The lines of the text are not straight and are not evenly spaced. The letters in the lower part of the text (after the lacuna on line 13) are neater and smaller than the letters in the first part of the inscription.[50]

The sarcophagus trough inscriptions correspond in size and style to the letters of the second part of the lid inscriptions. The letters are carved close together on the sixth line, and the text breaks off on the seventh line, consisting of nine characters that form the beginning of the text that begins after the lacuna on the 13th line of the lid inscription.[50] De Luynes and Turner believe that the inscription was free-hand traced directly on the stone without the use of typographic guides for letter-spacing, and that these tracings were followed by the carving artisan. The letters of the first three lines of the lid inscription are cut deeper and rougher than the rest of the text which indicates that the sculptor was either replaced or made to work more neatly.[50]

The external surface of the sarcophagus trough bears an isolated group of two Phoenician characters. De Luynes believes that they may have been trial carving marks made by the engraver of the inscription.[51]

The inscriptions of the sarcophagus of Eshmunazar are known to scholars as CIS I 3 and KAI 14; they are written in the Phoenician language using the Phoenician alphabet. They identify the king buried inside, tell of his lineage and temple construction feats, and warn against disturbing him in his repose.[52] The inscriptions also state that the "Lord of Kings" (the Achaemenid King of Kings) granted the Sidonian king "Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of Dagon, which are in the plain of Sharon" in recognition of his deeds.[52] According to Gibson the inscription "offers an unusually high proportion of literary parallels with the Hebrew Bible, especially its poetic sections".[48] French orientalist Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès wrote that the language of the inscription is "identical with Hebrew, except for the final inflections of a few words and certain expressions."[note 4][53]

As in other Phoenician inscriptions, the text seems to use no, or hardly any, matres lectionis, the letters that indicate vowels in Semitic languages. As in Aramaic, the preposition אית (ʾyt) is used as an accusative marker, while את (ʾt) is used for "with".[54]

Translations

Copies of the sarcophagus inscriptions were sent to scholars across the world,[55] and translations were published by well-known scholars (see below table).[56] Several other scholars worked on the translation, including the polymath Josiah Willard Gibbs, Hebrew language scholar William Henry Green, Biblical scholars James Murdock and Williams Jenks, and Syriac language expert Christian Frederic Crusé.[57] American missionaries William McClure Thomson and Eli Smith who were living in Ottoman Syria at the time of the discovery of the sarcophagus successfully translated most of the inscription by early 1855, but did not produce any publications.[57]

Belgian semitist Jean-Claude Haelewyck provided a hypothetical vocalization of the Phoenician text. A definitive vocalization is not possible because Phoenician is written without matres lectionis. Haelewyck based the premise of his vocalization on the affinity of the Phoenician and Hebrew languages, historical grammar, and ancient transcriptions.[58]

A list of early published translations is below:[56]

| Author | Memoir | Previous interpretations consulted | Published work |

|---|---|---|---|

| Edward E. Salisbury | 1855 | Phoenician Inscription of Sidon[59] | |

| William Wadden Turner | 3 July 1855 | The Sidon Inscription[60] | |

| Emil Rödiger | 15 June 1855 | Bemerkungen über die phönikische Inschrift eines am 19. Januar 1855 nahe bei Sidon gefundenen Königs-Sarkophag's[61] | |

| Franz Dietrich and Johann Gildemeister | 1 July 1855 | Zwei Sidonische Inschriften, eine griechische aus christlicher Zeit und eine altphönicische Königsinschrift[62] | |

| Ferdinand Hitzig | 30 September 1855 | Rödiger, Dietrich. | Die Grabschrift des Eschmunazar[63] |

| Konstantin Schlottmann | December 1855 | Rödiger, Dietrich, Hitzig, De Luynes and Ewald. | Die Inschrift Eschmunazar's, Königs der Sidonier[64] |

| Honoré Théodoric d'Albert de Luynes | 15 December 1855 | Mémoire sur le Sarcophage et inscription funéraire d'Esmunazar, roi de Sidon[65] | |

| Heinrich Ewald | 19 January 1856 | Salisbury, Turner, Roidiger, Dietrich, Hitzig. | Erklärung der grossen phönikischen inschrift von Sidon und einer ägyptisch-aramäischen : mit den zuverlässigen abbildern beider[66] |

| Jean-Joseph-Léandre Bargès | 1856 | Salisbury, Turner, Rödiger, Dietrich, Hitzig, De Luynes, Ewald (?). | Mémoire sur le sarcophage et l'inscription funéraire d'Eschmounazar, roi de Sidon[67] |

| Salomon Munk | 6 April 1856 | Salisbury, Turner, Rödiger, Dietrich, Hitzig, DeLuynes, Bargès. | Essais sur l'inscription phénicienne du sarcophage d'Eschmoun-'Ezer, roi de Sidon[68] |

| Moritz Abraham Levy | August 1856 | Salisbury, Turner, Rödiger, Dietrich, Hitzig, Ewald, De Luynes, Munk | Phönizisches Wörterbuch[69] |

English translation

| Line number |

Original Phoenician Inscription[52] | Transliteration[52][70] | Transcription[58] | English Translation[70] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 𐤁𐤉𐤓𐤇 𐤁𐤋 𐤁𐤔𐤍𐤕 𐤏𐤎𐤓 𐤅𐤀𐤓𐤁𐤏 𐤗𐤖𐤖𐤖𐤖 𐤋𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤉 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌

|

BYRḤ BL BŠNT ʿSR WʾRBʿ 14 LMLKY MLK ʾŠMNʿZR MLK ṢDNM | biyarḥ būl bišanōt[71] ʿasr we-ʾarbaʿ[72] lemulkiyū milk ʾèšmūnʿazar milk ṣīdōnīm | In the month of Bul, in the fourteenth year of the reign of king Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians |

| 2 | 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤕𐤁𐤍𐤕 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤃𐤁𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤋𐤀𐤌𐤓 𐤍𐤂𐤆𐤋𐤕

|

BN MLK TBNT MLK ṢDNM DBR MLK ʾŠMNʿZR MLK ṢDNM LʾMR NGZLT | bin milk tabnīt milk ṣīdōnīm dabar milk ʾèšmūnʿazar milk ṣīdōnīm līʾmōr nagzaltī[73] | son of king Tabnit, king of the Sidonians, king Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, said as follows: I was carried away |

| 3 | 𐤁𐤋 𐤏𐤕𐤉 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤎𐤊 𐤉𐤌𐤌 𐤀𐤆𐤓𐤌 𐤉𐤕𐤌 𐤁𐤍 𐤀𐤋𐤌𐤕 𐤅𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤀𐤍𐤊 𐤁𐤇𐤋𐤕 𐤆 𐤅𐤁𐤒𐤁𐤓 𐤆

|

BL ʿTY BN MSK YMM ʾZRM YTM BN ʾLMT WŠKB ʾNK BḤLT Z WBQBR Z | bal[74] ʿittiya bin masok yōmīm ʾazzīrīm yatum bin ʾalmatt[71] wešōkéb ʾanōkī[75] biḥallot zō webiqabr zè | before my time, son of a limited number of short days (or: son of a limited number of days I was cut off), an orphan, the son of a widow, and I am lying in this coffin and in this tomb, |

| 4 | 𐤁𐤌𐤒𐤌 𐤀𐤔 𐤁𐤍𐤕 𐤒𐤍𐤌𐤉 𐤀𐤕 𐤊𐤋 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤅𐤊𐤋 𐤀𐤃𐤌 𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤐𐤕𐤇 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤅

|

BMQM ʾŠ BNT QNMY ʾT KL MMLKT WKL ʾDM ʾL YPTḤ ʾYT MŠKB Z W | bammaqōm ʾéš banītī[76] qenummiya ʾatta kull[77] mamlokūt wekull[77] ʾadōm[77] ʾal yiptaḥ ʾiyat miškob zè we- | in a place which I have built. Whoever you are, king or (ordinary) man, may he (sic!) not open this resting-place and |

| 5 | 𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤁𐤒𐤔 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤍𐤌 𐤊 𐤀𐤉 𐤔𐤌 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤍𐤌 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤔𐤀 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤇𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁𐤉 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤏𐤌

|

ʾL YBQŠ BN MNM K ʾY ŠM BN MNM WʾL YŠʾ ʾYT ḤLT MŠKBY WʾL YʿM | -ʾal yebaqqéš bin(n)ū mīnumma kī ʾayy[74] śōmū bin(n)ū mīnumma weʾal yiššōʾ[78] ʾiyyōt[79] ḥallot miškobiya weʾal yaʿm- | may he not search in it after anything because nothing whatsoever has been placed into it. And may he not move the coffin of my resting-place, nor carry me |

| 6 | 𐤎𐤍 𐤁𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤔𐤍𐤉 𐤀𐤐 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤃𐤌𐤌 𐤉𐤃𐤁𐤓𐤍𐤊 𐤀𐤋 𐤕𐤔𐤌𐤏 𐤁𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤊 𐤊𐤋 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤅

|

SN BMŠKB Z ʿLT MŠKB ŠNY ʾP ʾM ʾDMM YDBRNK ʾL TŠMʿ BDNM K KL MMLKT W | -sénī bimiškob zè ʿalōt miškob šénīy ʾap ʾimʾiyyōt[79] ʾadōmīm[77] yedabberūnakā ʾal tišmaʿ baddanōm kakull[77] mamlokūt we- | away from this resting-place to another resting-place. Also if men talk to you do not listen to their chatter. For every king and |

| 7 | 𐤊𐤋 𐤀𐤃𐤌 𐤀𐤔 𐤉𐤐𐤕𐤇 𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤔 𐤉𐤔𐤀 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤇𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁𐤉 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤔 𐤉𐤏𐤌𐤎𐤍 𐤁𐤌

|

KL ʾDM ʾŠ YPTḤ ʿLT MŠKB Z ʾM ʾŠ YŠʾ ʾYT ḤLT MŠKBY ʾM ʾŠ YʿMSN BM | -kull[77] ʾadōm[77] ʾéš yiptaḥ ʿalōt miškob zè ʾīm ʾéš yiššōʾ[78] ʾiyyōt[79] ḥallot miškobiya ʾīm ʾéš yaʿmusénī bimi- | every (ordinary) man, who will open what is above this resting-place, or will lift up the coffin of my resting-place, or will carry me away from |

| 8 | 𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤊𐤍 𐤋𐤌 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤀𐤕 𐤓𐤐𐤀𐤌 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤒𐤁𐤓 𐤁𐤒𐤁𐤓 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤊𐤍 𐤋𐤌 𐤁𐤍 𐤅𐤆𐤓𐤏

|

ŠKB Z ʾL YKN LM MŠKB ʾT RPʾM WʾL YQBR BQBR WʾL YKN LM BN WZRʿ | -škob zè ʾal yakūn lōm miškob ʾōt[79] rapaʾīm weʾal yiqqabirū[80] nagzaltī[73] biqabr weʾal yakūnū lōm bin wezarʿ | this resting-place, may they not have a resting-place with the Rephaïm, may they not be buried in a tomb, and may they not have a son or offspring |

| 9 | 𐤕𐤇𐤕𐤍𐤌 𐤅𐤉𐤎𐤂𐤓𐤍𐤌 𐤄𐤀𐤋𐤍𐤌 𐤄𐤒𐤃𐤔𐤌 𐤀𐤕 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊(𐤕) 𐤀𐤃𐤓 𐤀𐤔 𐤌𐤔𐤋 𐤁𐤍𐤌 𐤋𐤒

|

TḤTNM WYSGRNM HʾLNM HQDŠM ʾT MMLK(T) ʾDR ʾŠ MŠL BNM LQ | taḥténōm weyasgirūnōm hāʾalōnīm haqqadošīm ʾét mamlokū[t] ʾaddīr ʾéš mōšél bin(n)ōm laq- | after them. And may the sacred gods deliver them to a mighty king who will rule them in order |

| 10 | 𐤑𐤕𐤍𐤌 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤃𐤌 𐤄𐤀 𐤀𐤔 𐤉𐤐𐤕𐤇 𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤔 𐤉𐤔𐤀 𐤀𐤉𐤕

|

ṢTNM ʾYT MMLKT ʾM ʾDM Hʾ ʾŠ YPTḤ ʿLT MŠKB Z ʾM ʾŠ YŠʾ ʾYT | -ṣṣotinōm/laqaṣṣōtinōm ʾiyyōt[79] mamlokūt ʾim ʾadōm[77] hūʾa ʾéš yiptaḥ ʿalōt miškob zè ʾīm ʾéš yiššōʾ[78] ʾiyyōt[79] | to exterminate them, the king or this (ordinary) man who will open what is over this resting-place or will lift up |

| 11 | 𐤇𐤋𐤕 𐤆 𐤅𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤆𐤓𐤏 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤕 𐤄𐤀 𐤀𐤌 𐤀𐤃𐤌𐤌 𐤄𐤌𐤕 𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤊𐤍 𐤋𐤌 𐤔𐤓𐤔 𐤋𐤌𐤈 𐤅

|

ḤLT Z WʾYT ZRʿ MMLT Hʾ ʾM ʾDMM HMT ʾL YKN LM ŠRŠ LMṬ W | ḥallot zè weʾiyat zarʿ mamlo[kū]t hūʾa ʾim ʾadōmīm[77] humatu ʾal yakūnū lōm šurš lamaṭṭō we- | this coffin, and (also) the offspring of this king or of those (ordinary) men. They shall not have root below or |

| 12 | 𐤐𐤓 𐤋𐤌𐤏𐤋 𐤅𐤕𐤀𐤓 𐤁𐤇𐤉𐤌 𐤕𐤇𐤕 𐤔𐤌𐤔 𐤊 𐤀𐤍𐤊 𐤍𐤇𐤍 𐤍𐤂𐤆𐤋𐤕 𐤁𐤋 𐤏𐤕𐤉 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤎

|

PR LMʿL WTʾR BḤYM TḤT ŠMŠ K ʾNK NḤN NGZLT BL ʿTY BN MS | -parī lamaʿlō wetuʾr baḥayyīm taḥt šamš ka ʾanōkī[75] nāḥān nagzaltī[73] bal[74] ʿittiya bin maso- | fruit above or appearance in the life under the sun. For I who deserve mercy, I was carried away before my time, son of a limited |

| 13 | 𐤊 𐤉𐤌𐤌 𐤀𐤆𐤓𐤌 𐤉𐤕𐤌 𐤁𐤍 𐤀𐤋𐤌𐤕 𐤀𐤍𐤊 𐤊 𐤀𐤍𐤊 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤁𐤍

|

K YMM ʾZRM YTM BN ʾLMT ʾNK K ʾNK ʾŠMNʿZR MLK ṢDNM BN | -k yōmīm ʾazzīrīm yatum bin ʾalmatt[71] ʾanōkī[75] ka ʾanōkī[75] ʾèšmūnʿazar milk ṣīdōnīm bin | number of short days (or: son of a limited number of days I was cut off), I an orphan, the son of a widow. For I, Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, son of |

| 14 | 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤕𐤁𐤍𐤕 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤁𐤍 𐤁𐤍 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤅𐤀𐤌𐤉 𐤀𐤌𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕

|

MLK TBNT MLK ṢDNM BN BN MLK ʾŠMNʿZR MLK ṢDNM WʾMY ʾM ʿŠTRT | milk tabnīt milk ṣīdōnīm bin bin milk ʾèšmūnʿazar milk ṣīdōnīm weʾummī[81] ʾamotʿaštart | king Tabnit, king of the Sidonians, grandson of king Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, and my mother Amo[t]astart, |

| 15 | 𐤊𐤄𐤍𐤕 𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕 𐤓𐤁𐤕𐤍 𐤄𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤁𐤕 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍𐤏𐤆𐤓 𐤌𐤋𐤊 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤀𐤌 𐤁𐤍𐤍 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤁𐤕

|

KHNT ʿŠTRT RBTN HMLKT BT MLK ʾŠMNʿZR MLK ṢDNM ʾM BNN ʾYT BT | kōhant ʿaštart rabbotanū hammilkōt[71] bat milk ʾèšmūnʿazar milk ṣīdōnīm ʾ[š] banīnū ʾiyyōt[79] bīté | priestess of Ashtart, our lady, the queen, daughter of king Eshmunazar, king of the Sidonians, (it is we) who have built the temples |

| 16 | 𐤀𐤋𐤍𐤌 𐤀𐤉𐤕 (𐤁𐤕 𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓)𐤕 𐤁𐤑𐤃𐤍 𐤀𐤓𐤑 𐤉𐤌 𐤅𐤉𐤔𐤓𐤍 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕 𐤔𐤌𐤌 𐤀𐤃𐤓𐤌 𐤅𐤀𐤍𐤇𐤍

|

ʾLNM ʾYT [BT ʿŠTR]T BṢDN ʾRṢ YM WYŠRN ʾYT ʿŠTRT ŠMM ʾDRM WʾNḤN | ʾalōnīm ʾiyyōt[79] [bīt ʿaštar]t biṣīdōn ʾarṣ yim weyōšibnū ʾiyyōt[79] ʿaštart šamém ʾaddīrim weʾanaḥnū | of the gods, [the temple of Ashtar]t in Sidon, the land of the sea. And we have placed Ashtart (in) the mighty heavens (or: in Shamem-Addirim?). And it is we |

| 17 | 𐤀𐤔 𐤁𐤍𐤍 𐤁𐤕 𐤋𐤀𐤔𐤌𐤍 (𐤔)𐤓 𐤒𐤃𐤔 𐤏𐤍 𐤉𐤃𐤋𐤋 𐤁𐤄𐤓 𐤅𐤉𐤔𐤁𐤍𐤉 𐤔𐤌𐤌 𐤀𐤃𐤓𐤌 𐤅𐤀𐤍𐤇𐤍 𐤀𐤔 𐤁𐤍𐤍 𐤁𐤕𐤌

|

ʾŠ BNN BT LʾŠMN [Š]R QDŠ ʿN YDLL BHR WYŠBNY ŠMM ʾDRM WʾNḤN ʾŠ BNN BTM | éš banīnū bīt laʾèšmūn [śa]r qudš ʿīn ydll bihar weyōšibnūyū šamém ʾaddīrim weʾanaḥnū ʾéš banīnū bītīm | who have built a temple for Eshmun, the prince of the sanctuary of the source of YDLL in the mountains, and we have placed him (in) the mighty heavens (or: in Shamem-Addirim?). And it is we who have built temples |

| 18 | 𐤋𐤀𐤋𐤍 𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤁𐤑𐤃𐤍 𐤀𐤓𐤑 𐤉𐤌 𐤁𐤕 𐤋𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤑𐤃𐤍 𐤅𐤁𐤕 𐤋𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕 𐤔𐤌 𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤅𐤏𐤃 𐤉𐤕𐤍 𐤋𐤍 𐤀𐤃𐤍 𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤌

|

LʾLN ṢDNM BṢDN ʾRṢ YM BT LBʿL ṢDN WBT LʿŠTRT ŠM BʿL WʿD YTN LN ʾDN MLKM | aʾalōné ṣīdōnīm biṣīdōn ʾarṣyim bīt labaʿl ṣīdōn webīt laʿaštart šim baʿl weʿōd yatan lanū ʾadōn milakīm[77] | for the gods of the Sidonians in Sidon, the land of the sea, a temple for Baal of Sidon, and a temple for Ashtart, the Name of Baal. Moreover, the lord of kings gave us |

| 19 | 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤃𐤀𐤓 𐤅𐤉𐤐𐤉 𐤀𐤓𐤑𐤕 𐤃𐤂𐤍 𐤄𐤀𐤃𐤓𐤕 𐤀𐤔 𐤁𐤔𐤃 𐤔𐤓𐤍 𐤋𐤌𐤃𐤕 𐤏𐤑𐤌𐤕 𐤀𐤔 𐤐𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤅𐤉𐤎𐤐𐤍𐤍𐤌

|

ʾYT DʾR WYPY ʾRṢT DGN HʾDRT ʾŠ BŠD ŠRN LMDT ʿṢMT ʾŠ PʿLT WYSPNNM | iyat duʾr weyapay ʾarṣōt dagōn hāʾaddīrōt ʾéš biśadé šarōn lamiddot ʿaṣūmot ʾéš paʿaltī weyasapnūném | Dor and Joppa, the mighty lands of Dagon, which are in the Plain of Sharon, as a reward for the brilliant action I did. And we have annexed them |

| 20 | 𐤏𐤋𐤕 𐤂𐤁𐤋 𐤀𐤓𐤑 𐤋𐤊𐤍𐤍𐤌 𐤋𐤑𐤃𐤍𐤌 𐤋𐤏𐤋(𐤌) 𐤒𐤍𐤌𐤉 𐤀𐤕 𐤊𐤋 𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤅𐤊𐤋 𐤀𐤃𐤌 𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤐𐤕𐤇 𐤏𐤋𐤕𐤉

|

ʿLT GBL ʾRṢ LKNNM LṢDNM LʿL[M] QNMY ʾT KL MMLKT WKL ʾDM ʾL YPTḤ ʿLTY | alōt gubūl(é) ʾarṣlakūniném laṣṣīdōnīm laʿōlo[m] qenummiya ʾatta kull[77] mamlokūt wekull[77] ʾadōm[77] ʾal yiptaḥ ʿalōtiya | to the boundary of the land, so that they would belong to the Sidonians for ever. Whoever you are, king or (ordinary) man, do not open what is above me |

| 21 | 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤏𐤓 𐤏𐤋𐤕𐤉 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤏𐤌𐤎𐤍 𐤁𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁 𐤆 𐤅𐤀𐤋 𐤉𐤔𐤀 𐤀𐤉𐤕 𐤇𐤋𐤕 𐤌𐤔𐤊𐤁𐤉 𐤋𐤌 𐤉𐤎𐤂𐤓𐤍𐤌

|

WʾL YʿR ʿLTY WʾL YʿMSN BMŠKB Z WʾL YŠʾ ʾYT ḤLT MŠKBY LM YSGRNM | weʾal yaʿar ʿalōtiya weʾal yaʿmusénī bimiškob zè weʾal yiššōʾ[78] ʾiyyōt[79] ḥallot miškobiya lamā yasgirūnōm | and do not uncover what is above me and do not carry me away from this resting-place and do not lift up the coffin of my resting-place. Otherwise, |

| 22 | 𐤀𐤋𐤍𐤌 𐤄𐤒𐤃𐤔𐤌 𐤀𐤋 𐤅𐤉𐤒𐤑𐤍 𐤄𐤌𐤌𐤋𐤊𐤕 𐤄𐤀 𐤅𐤄𐤀𐤃𐤌𐤌 𐤄𐤌𐤕 𐤅𐤆𐤓𐤏𐤌 𐤋𐤏𐤋𐤌

|

ʾLNM HQDŠM ʾL WYQṢN HMMLKT Hʾ WHʾDMM HMT WZRʿM LʿLM | alōnīm haqqadošīm ʾillè weyeqaṣṣūna hammamlokūt hūʾa wehāʾadōmīm[77] humatu wezarʿōm laʿōlom[74] | the sacred gods will deliver them and cut off this king and those (ordinary) men and their offspring for ever. |

Dating and attribution

The Egyptian-style sarcophagi found in Sidon were originally made in Egypt for members of the Ancient Egyptian elite, but were then transported to Sidon and repurposed for the burial of Sidonian royalty. The manufacture of this style of sarcophagi in Egypt ceased around 525 BC with the fall of the 26th dynasty.[82][83] Gibson and later scholars believe that the sarcophagi were captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC.[84] Herodotus recounts an event in which Cambyses II "ransacked a burial ground at Memphis, where coffins were opened up and the dead bodies they contained were examined", possibly providing the occasion on which the sarcophagi were removed and reappropriated by his Sidonian subjects.[82][85][86]

Whereas the Tabnit sarcophagus, belonging to the father of Eshmunazar II, reemployed a sarcophagus already dedicated on its front with a long Egyptian inscription in the name of an Egyptian general, the sarcophagus used for Eshmunazar II was new and was inscribed with a full-length dedication in Phoenician on a clean surface. According to French archaeologist and epigrapher René Dussaud, the sarcophagus may have been ordered by his surviving mother, Queen Amoashtart, who arranged for the inscription to be made.[87]

These sarcophagi (a third one probably belonged to Queen Amoashtart), are the only Egyptian sarcophagi that have ever been found outside of Egypt.[88]

Significance

The discovery of the Magharet Abloun hypogeum and of Eshmunazar II's sarcophagus caused a sensation in France, which led Napoleon III, the Emperor of the French, to dispatch a scientific mission to Lebanon headed by Ernest Renan.[89][27][90]

Significance of the inscription

The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery; it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper.[91][note 5] Furthermore, this engraving forms the longest and most detailed Phoenician inscription ever found anywhere up to that point, and is now the second longest extant Phoenician inscription after the Karatepe bilingual.[93][91][92][94]

Due to its level of preservation and length, the inscription offered valuable knowledge about the charactarestics of the Phoenician language and, more specifically, the Tyro-Sidonian dialect. Additionally, the inscription displayed notable similarities to other Semitic languages, evident in its idiomatic expressions, word combinations, and the use of repetition.[25]

Stylistic impact on later Phoenician sarcophagi

See also

- Temple of Eshmun - Ancient temple complex built by Eshmunazar II.

- Alexander Sarcophagus - Ancient sarcophagus discovered in the royal necropolis of Sidon.

- Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon - Ancient sarcophagus discovered in the royal necropolis of Sidon.

- Ford Collection sarcophagi - A collection of ancient anthropoid Phoenician sarcophagi unearthed in Sidon.

Notes

- ↑ Bankes, who was the guest of British adventurer and archaeologist Hester Stanhope, visited the vast necropolis that was accidentally discovered in 1814, in Wadi Abu Ghiyas at the foot of the towns of Bramieh and Hlaliye, northeast of Sidon. He sketched the layout of one of the sepulchral caves, made faithful watercolor copies of its frescoes, and removed two fresco panels, which he sent to England. The panels are now in the National Trust and County Record Office in Dorchester[24]

- ↑ The date of the discovery figures at the top of the copy of the sarcophagus inscription made by Van Dyke (p.380).[26] Other sources provide a later date (see Jidéjian).[27]

- ↑ Dimensions given in de Luynes report are 2.45 metres (8.0 ft) tall by 1.4 metres (4.6 ft) wide.[38]

- ↑ The following is the quote from Bargès in French followed by an English translation: Sous le rapport de la linguistique, il nous fournit de précieux renseignements sur la nature de la langue parlée en Phénicie quatre siècles environ avant l'ère chrétienne; cette langue s'y montre identique avec l'hébreu, sauf les inflexions finales de quelques mots et certaines expressions, en très-petit nombre, qui ne se retrouvent pas dans les textes bibliques parvenus jusqu'à nous ; le fait de l'hébreu écrit et parlé à Sidon, à une époque où les Juifs de retour de la captivité n'entendaient déjà plus cette langue, est une preuve qu'elle s'est conservée chez les Phéniciens plus longtemps que chez les Hébreux eux-mêmes. [Translation: With regard to linguistics, it provides us with valuable information on the nature of the language spoken in Phoenicia about four centuries before the Christian era; this language is shown to be identical with Hebrew, except for the final inflections of a few words and certain expressions, in very small numbers, which are not found in the biblical texts which have come down to us; the fact that Hebrew was written and spoken in Sidon, at a time when the Jews returning from captivity no longer heard this language, is proof that it was preserved among the Phoenicians longer than among the Hebrews themselves.][53]

- ↑ Lehmann wrote in 2013: "Alas, all these were either late or Punic, and came from Cyprus, from the ruins of Kition, from Malta, Sardinia, Athens, and Carthage, but not yet from the Phoenician homeland. The first Phoenician text as such was found as late as 1855, the Eshmunazor sarcophagus inscription from Sidon;"[92] Turner wrote in 1855: "Its interest is greater both on this account and as being the first inscription properly so-called that has yet been found in Phoenicia proper, which had previously furnished only some coins and an inscribed gem. It is also the longest inscription hitherto discovered, that of Marseilles—which approaches it the nearest in the form of its characters, the purity of its language, and its extent — consisting of but 21 lines and fragments of lines.[93]

References

Citations

- ↑ Hitti 1967, p. 135.

- ↑ Jean 1947, p. 267.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, p. 22.

- ↑ Elayi 2006, p. 5, 22.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, p. 6.

- ↑ Lipiński 1995, pp. 135–451.

- ↑ Ackerman 2013, p. 158–178.

- ↑ Elayi 1997, p. 69.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Elayi & Sapin 1998, p. 153.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2012, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Motta 2015, p. 5.

- ↑ Jigoulov 2016, p. 150.

- ↑ Jigoulov 2016, p. 120–121.

- ↑ Saidah 1983.

- ↑ Torrey 1919.

- ↑ Renan 1864, p. 362.

- ↑ Hamdy Bey & Reinach 1892.

- ↑ Luynes 1856.

- ↑ Macridy 1904.

- ↑ Gras, Rouillard & Teixidor 1991, p. 127.

- ↑ Ward 1994, p. 316.

- ↑ Luynes 1856, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Lewis, Sartre-Fauriat & Sartre 1996, p. 61.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Jidéjian 2000, p. 15–16.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Long 1997, p. 261.

- ↑ Journal of Commerce correspondent 1855, p. 380.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Jidéjian 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 Luynes 1856, p. 1.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Caubet & Prévotat 2013.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Klat 2002, p. 101.

- ↑ Journal of Commerce correspondent 1855, pp. 379–381.

- ↑ Bargès 1856, p. 1.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 Klat 2002, p. 102.

- ↑ Renan 1864, p. 402.

- ↑ Fawaz 1983, p. 89Accurate title of Habib Abela

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Tahan 2017, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 Holloway, Davis & Drake 1855, p. 1.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Luynes 1856, p. 2.

- ↑ Chancellerie du Consulat général de France à Beyrouth 1855.

- ↑ Bargès 1856, p. 40.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 King 1887, p. 135.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Luynes 1856, p. 3.

- ↑ Jidéjian 1998, p. 7.

- ↑ Renan 1864, p. 414.

- ↑ Jidéjian 2000, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Buhl 1959, p. 34.

- ↑ Turner 1860, p. 48.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Gibson 1982, p. 105.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Turner 1860, pp. 51–52.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Turner 1860, p. 52.

- ↑ Luynes 1856, p. 5.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Rosenthal 2011, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Bargès 1856, p. 39.

- ↑ Donner & Röllig 2002, p. 3.

- ↑ Turner 1860, pp. 48–50.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Turner 1860, p. 49.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Salisbury 1855, p. 230.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Haelewyck 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Salisbury 1855, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Turner 1855, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Rödiger 1855, pp. 648–658.

- ↑ Dietrich & Gildemeister 1855, pp. 35–37.

- ↑ Hitzig 1855, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Schlottmann 1867, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Luynes 1856, pp. 4–9.

- ↑ Ewald 1856, pp. 70–71.

- ↑ Bargès 1856, pp. 6–12.

- ↑ Munk 1856, pp. 13–16.

- ↑ Levy 1864.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Haelewyck 2012, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 71.3 Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 207.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 209.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Gzella 2011, p. 70.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Gzella 2011, p. 71.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 210.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 213.

- ↑ 77.00 77.01 77.02 77.03 77.04 77.05 77.06 77.07 77.08 77.09 77.10 77.11 77.12 77.13 Gzella 2011, p. 63.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 78.3 Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 218.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 79.4 79.5 79.6 79.7 79.8 79.9 Gzella 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Amadasi Guzzo 2019, p. 217.

- ↑ Gzella 2011, p. 61.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Elayi 2006, p. 6.

- ↑ Versluys 2010, p. 7–14.

- ↑ Gibson 1982, p. 102.

- ↑ Kelly 1987, p. 48–49.

- ↑ Buhl 1959, p. 32–34.

- ↑ Dussaud, Deschamps & Seyrig 1931, Plaque 29.

- ↑ Kelly 1987, p. 48.

- ↑ Contenau 1920, p. 19.

- ↑ Mejcher-Atassi & Schwartz 2016, p. 59.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Van Dyck 1864, p. 67.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 Lehmann 2013, p. 213.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Turner 1855, p. 259.

- ↑ Schade 2006, p. 154.

Sources

- Ackerman, Susan (2013). "The Mother of Eshmunazor, Priest of Astarte: A study of her cultic role". Die Welt des Orients 43 (2): 158–178. doi:10.13109/wdor.2013.43.2.158. ISSN 0043-2547. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23608853.

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2012). "Sidon et ses sanctuaires" (in fr). Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (Presses Universitaires de France) 106: 5–18. doi:10.3917/assy.106.0005. ISSN 0373-6032. https://www.jstor.org/stable/42771737.

- Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Giulia (2019). "The Language". The Oxford Handbook of the Phoenician and Punic Mediterranean. New York City , United States: Oxford University Press. pp. 199–222. ISBN 9780190499341.

- Bargès, Jean Joseph Léandre (1856) (in fr). Mémoire sur le sarcophage et l'inscription funéraire d'Eschmounazar, roi de Sidon. Paris: B. Duprat. https://books.google.com/books?id=RtYOAAAAQAAJ.

- Buhl, Marie-Louise (1959). "The late Egyptian anthropoid stone sarcophagi" (in da). Nationalmuseets Skrifter. Arkæologisk-historisk række (København Nationalmuseet) 6. https://books.google.com/books?id=4adwmQEACAAJ&q=The+late+Egyptian+anthropoid+stone+sarcophagi.

- Caubet, Annie; Prévotat, Arnaud (2013). "Sarcophagus of Eshmunazar II, king of Sidon". Musée du Louvre. https://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/sarcophagus-eshmunazar-ii-king-sidon.

- Chancellerie du Consulat général de France à Beyrouth (24 April 1855). Litige entre Habib Abela el Alphonse Durighello à propos du sarcophage d'Eshmunazor II (Report). http://www.ahlebanon.com/images/PDF/Issue%2016%20-%20Autumn%202002/Litige%20entre%20Habib%20Abela%20et%20Alphonse%20Durighello%20a%20Propos%20du%20Sarcophage%20d'Eshunazor%20II%20-%2024%20Avril%201855.pdf.

- Contenau, Georges (1920). "Mission archéologique à Sidon (1914)" (in fr). Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire 1 (1): 16–55. doi:10.3406/syria.1920.2837. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1920_num_1_1_2837.

- Dietrich, Franz; Gildemeister, Johann (1855) (in fr). Zwei Sidonische Inschriften, eine griechische aus christlicher Zeit und eine altphönicische Königsinschrift. Marburg: N.G. Elwer. https://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/de/fs3/object/display/bsb10250784_00007.html. Retrieved 2021-01-21.

- Donner, Herbert; Röllig, Wolfgang (2002) (in phn, arc). Kanaanäische und aramäische Inschriften. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447045872. https://books.google.com/books?id=M5RS_DICJ5AC.

- Dussaud, René; Deschamps, Paul; Seyrig, Henri (1931) (in fr). La Syrie antique et médiévale illustrée. Tome XVII. Paris: Librairie orientaliste Paul Geuthner. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k12905389/f86.item.zoom. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- Elayi, Josette (2006). "An updated chronology of the reigns of Phoenician kings during the Persian period (539–333 BCE)". Digitorient (Collège de France – UMR7912). http://www.digitorient.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2006/10/2Updated%20Chronology1.pdf.

- Elayi, Josette; Sapin, Jean (1998) (in en). Beyond the River: New Perspectives on Transeuphratene. Sheffield: Sheffield Academy Press. ISBN 9781850756781. https://books.google.com/books?id=goCtAwAAQBAJ.

- Elayi, Josette (1997). "Pouvoirs locaux et organisation du territoire des cités phéniciennes sous l'Empire perse achéménide" (in fr). Espacio, Tiempo y Forma. 2, Historia antigua (Editorial UNED) 10: 63–77.

- Ewald, Heinrich (1856) (in de). Erklärung der grossen phönikischen inschrift von Sidon und einer ägyptisch-aramäischen, mit den zuverlässigen abbildern beider. Sprachwissenschaftliche abhandlungen. 2 pt. Das vierte Ezrabuch nach seinem zeitalter, seinen arabischen übersezungen und einer neuen wiederherstellung. Göttingen: Dieterich. https://books.google.com/books?id=QS3gAAAAMAAJ.

- Fawaz, Leila Tarazi (1983) (in en). Merchants and Migrants in Nineteenth-Century Beirut. Harvard Middle Eastern studies. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674333550. ISBN 9780674333550. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.4159/harvard.9780674333550/html.

- Gibson, John C. L. (1982) (in en). Textbook of Syrian Semitic Inscriptions. 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 9780198131991. https://books.google.com/books?id=8dFiAAAAMAAJ.

- Gras, Michel; Rouillard, Pierre; Teixidor, Javier (1991) (in en). The Phoenicians and Death. Faculty of Arts and Sciences, American University of Beirut. https://books.google.com/books?id=-jJ4ygAACAAJ.

- Gzella, Holger (2011). "Phoenician". in Gzella, Holger. Languages from the World of the Bible. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 55–75. doi:10.1515/9781934078631.111. ISBN 978-1-934-07863-1.

- Haelewyck, Jean-Claude (2012). "The Phoenician inscription of Eshmunazar : An attempt at vocalization". Bulletin de l'Académie Belge pour l'Étude des Langues Anciennes et Orientales (Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium: Académie Belge pour l'Etude des Langues Anciennes et Orientales (ABELAO)) 1: 77–98. doi:10.14428/BABELAO.VOL1.2012.19803. https://ojs.uclouvain.be/index.php/babelao/article/view/19803/18423.

- Hamdy Bey, Osman; Reinach, Théodore (1892) (in fr). Une nécropole royale à Sidon : fouilles de Hamdy Bey. Texte. Paris: Ernest Leroux. doi:10.11588/DIGLIT.5197. https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/hamdybey1892bd1.

- Hitti, Philip Khuri (1967) (in en). Lebanon in History: From the Earliest Times to the Present. London: Macmillan. https://books.google.com/books?id=RG1tAAAAMAAJ.

- Hitzig, Ferdinand (1855) (in de). The epitaph of the Eschmunazar. Leipzig: S. Hirzel. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_xow-AAAAcAAJ.

- Holloway, B. P.; Davis, B. W.; Drake, J. S. (1855). "Important archaeological discoveries in Sidon". https://newspapers.library.in.gov/?a=d&d=RPW18550427.1.1&e=-------en-20--1--txt-txIN-------.

- Jean, Charles François (1947). "L'étude du milieu biblique" (in fr). Nouvelle Revue Théologique: 245–270. https://www.nrt.be/fr/articles/l-etude-du-milieu-biblique-2832. Retrieved 2021-02-10.

- Jidéjian, Nina (1998) (in fr). L'archéologie au Liban: sur les traces des diplomates, archéologues amateurs et savants. Beirut: Dar an-Nahar. ISBN 9782842891022. https://books.google.com/books?id=VT1mAAAAMAAJ.

- Jidéjian, Nina (2000). "Greater Sidon and its "Cities of the Dead"". National Museum News (Ministère de la Culture - Direction Générale des Antiquités (Liban)) (10): 15–24. http://www.ahlebanon.com/images/PDF/Issue%2010%20-%20The%20Millenium%20Edition/Greater%20Sidon%20and%20its%20Cities%20Of%20The%20Dead%20-%20Nina%20Jidejian.pdf.

- Jigoulov, Vadim S. (2016) (in en). The Social History of Achaemenid Phoenicia: Being a Phoenician, Negotiating Empires. Bible World. Oxford: Routledge. ISBN 9781134938162. https://books.google.com/books?id=prfsCwAAQBAJ.

- Journal of Commerce correspondent (11 February 1855). "A voice from the ancient dead: Who shall interpret it?" (in en). United States magazine of science, art, manufactures, agriculture, commerce and trade. New York, N.Y.: J.M. Emerson & Company. pp. 379–381. https://books.google.com/books?id=KcpBAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA379.

- Kelly, Thomas (1987). "Herodotus and the Chronology of the Kings of Sidon". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research (268): 48–49. doi:10.2307/1356993. ISSN 0003-097X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1356993. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

- King, James (1887). "The Saida discoveries". The Churchman (Hartford, Conn.: George S. Mallory) 2: 134–144. http://biblicalstudies.gospelstudies.org.uk/pdf/churchman/002-03_134.pdf.

- Klat, Michel G. (2002). "The Durighello Family". Archaeology & History in Lebanon (London: Lebanese British Friends of the National Museum) (16): 98–108. http://www.ahlebanon.com/images/PDF/Issue%2016%20-%20Autumn%202002/The%20Durighello%20Family%20-%20Michel%20G.%20Klat.pdf.

- Lehmann, Reinhard G. (2013). "Wilhelm Gesenius and the Rise of Phoenician Philology". in Schorch, Stefan (in de). Biblische Exegese und hebräische Lexikographie: Das "Hebräisch-deutsche Handwörterbuch" von Wilhelm Gesenius als Spiegel und Quelle alttestamentlicher und hebräischer Forschung, 200 Jahre nach seiner ersten Auflage. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110267044. OCLC 902599516. http://www.hebraistik.uni-mainz.de/Dateien/Lehmann_Gesenius-Phoenix_2013.pdf.

- Levy, Moritz Abraham (1864) (in de). Phonizisches Worterbuch. Breslau: Schletter. https://books.google.com/books?id=0usZTNfns9EC.

- Lewis, Norman Nicholson; Sartre-Fauriat, Annie; Sartre, Maurice (1996). "William John Bankes.Travaux en Syrie d'un voyageur oublié". Syria. Archéologie, Art et histoire 73 (1): 57–95. doi:10.3406/syria.1996.7502. https://www.persee.fr/doc/syria_0039-7946_1996_num_73_1_7502.

- Lipiński, Edward (1995) (in fr). Dieux et déesses de l'univers phénicien et punique. Leuven: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789068316902. https://books.google.com/books?id=RKxLnTEqXwIC.

- Long, Gary Alan (1997). Meyers, Eric M.. ed (in en). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195112160. https://books.google.com/books?id=kSgZAQAAIAAJ.

- Luynes, Honoré Théodoric Paul Joseph d'Albert duc de (1856) (in fr). Mémoire sur le sarcophage et inscription funéraire d'Esmunazar, Roi de Sidon. Henri Plon. https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb10219632?q=%28Mémoire+sur+le+Sarcophage+et+inscription+funéraire+%29&page=6,7. Retrieved 2021-01-22.

- Macridy, Theodor (1904) (in fr). Le temple d'Echmoun à Sidon: fouilles du Musée impérial ottoman. Paris: Librairie Victor Lecoffre. https://books.google.com/books?id=6yK4GwAACAAJ.

- Mejcher-Atassi, S.; Schwartz, J.P. (2016). "Between Looters and Private Collectors: The Tragic Fate of Lebanese Antiquities". Archives, Museums and Collecting Practices in the Modern Arab World. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317178842. https://books.google.com/books?id=yG83DAAAQBAJ&pg=PA59. Retrieved 27 January 2022.

- Motta, Rosa Maria (2015) (in en). Material culture and cultural identity: A study of Greek and Roman coins from Dora. Oxford: Archaeopress Publishing Ltd. ISBN 9781784910938. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZS1GEAAAQBAJ.Commerce correspondent

- Munk, Salomon (1856) (in fr). Essais sur l'inscription phénicienne du sarcophage d'Eschmoun-'Ezer, roi de Sidon: Mit 1 Tafel (Extr. no 5 de l'année 1856 du j. as.). Paris: Imprimerie Impériale. https://books.google.com/books?id=_4w-AAAAcAAJ.

- Renan, Ernest (1864) (in fr). Mission de Phénicie Dirigée par M. Ernest Renan. Paris: Imprimerie impériale. https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k5529563s.

- Rödiger, Emil (1855). "Bemerkungen über die phönikische Inschrift eines am 19. Januar 1855 nahe bei Sidon gefundenen Königs-Sarkophag's" (in de). Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 9 (3/4): 647–659. ISSN 0341-0137. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43359455.

- Rosenthal, Franz (2011). "X - Canaanite and Aramaic Inscriptions". in Pritchard, James B. (in en). The Ancient Near East: An Anthology of Texts and Pictures. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691147260. https://archive.org/details/ancientneareasta0000unse/page/310/mode/2up.

- Saidah, Roger (1983). "Nouveaux éléments de datation de la céramique de l'Age du Fer au Levant". Atti del I Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e Punici Libreria della SpadaLibri esauriti antichi e moderni Libri rari e di pregio da tutto il mondo. https://www.libreriadellaspada.com/atti_del_i_congresso_internazionale_di_studi_fenici_e_punici.html.

- Salisbury, Edward Elbridge (1855). "Phœnician Inscription of Sidon". Journal of the American Oriental Society 5: 227–243. doi:10.2307/592226. ISSN 0003-0279. https://www.jstor.org/stable/592226.

- Schade, Aaron (2006) (in en). A Syntactic and Literary Analysis of Ancient Northwest Semitic Inscriptions. Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 9780773455269. https://books.google.com/books?id=QTvuAAAAMAAJ.

- Schlottmann, Konstantin (1867) (in de). Die Inschrift Eschmunazar's, Königs der Sidonier. Halle: Buchdruckerei des Waisenhauses. https://archive.org/details/4769321.

- Tahan, Lina G. (2017). "Trafficked Lebanese Antiquities: Can They Be Repatriated from European Museums?" (in en). Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology & Heritage Studies 5 (1): 27–35. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027. ISSN 2166-3556. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.5.1.0027.

- Torrey, Charles C. (1919). "A Phoenician Necropolis at Sidon". The Annual of the American School of Oriental Research in Jerusalem 1: 1–27. doi:10.2307/3768461. ISSN 1933-2505. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3768461.

- Turner, William Wadden (1855). "The Sidon Inscription, with a Translation and Notes". Journal of the American Oriental Society 5: 243–259. doi:10.2307/592227. ISSN 0003-0279. https://www.jstor.org/stable/592227.

- Turner, William Wadden (1860). "Remarks on the Phœnician Inscription of Sidon". Journal of the American Oriental Society (American Oriental Society) 7: 48–59. doi:10.2307/592156. ISSN 0003-0279. https://www.jstor.org/stable/592156.

- Van Dyck, Cornelius Van Alen (1864) (in en). Transactions of the Albany Institute. IV. Albany: Webster and Skinners. pp. 67–72. https://books.google.com/books?id=_FLMAAAAMAAJ.

- Versluys, Miguel John (2010). "Understanding Egypt In Egypt And Beyond". in Bricault, Laurent. Isis on the Nile. Egyptian Gods in Hellenistic and Roman Egypt - Proceedings of the IVth International Conference of Isis Studies, Liège, November 27-29, 2008 : Michel Malaise in honorem. Religions in the Graeco-Roman world, 171. Leiden: Brill. pp. 7–36. doi:10.1163/EJ.9789004188822.I-364.10. ISBN 9789004210868. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Understanding-Egypt-In-Egypt-And-Beyond-Versluys/ccc591b97d87f3c44ee10d67ba18ba6431b87255.

- Vlassopoulos, Kostas (2013) (in en). Greeks and Barbarians. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107244269. https://books.google.com/books?id=gQnwcbRFAsoC&pg=PA271.

- Vogüé, Marie-Eugène-Melchior de (1880). "Note sur la forme du tombeau d'Eschmounazar" (in fr). Journal Asiatique Ou Recueil de Memoires 15: 278–286. http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.317242.

- Ward, William A. (1994). "Archaeology in Lebanon in the Twentieth Century" (in en). The Biblical Archaeologist 57 (2): 66–85. doi:10.2307/3210385. ISSN 0006-0895. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/10.2307/3210385.

External links