Social:Ashokan Prakrit

| Ashokan Prakrit | |

|---|---|

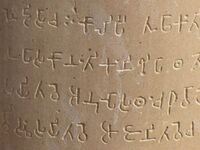

Ashokan Prakrit inscribed in the Brahmi script at Sarnath. | |

| Region | South Asia |

| Era | 268—232 BCE |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | Proto-Indo-European

|

| Brahmi, Kharoshthi | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

Ashokan Prakrit (or Aśokan Prākṛta) is the Middle Indo-Aryan dialect continuum used in the Edicts of Ashoka, attributed to Emperor Ashoka of the Mauryan Empire who reigned 268 BCE to 232 BCE.[1] The Edicts are inscriptions on monumental pillars and rocks throughout the Indian subcontinent that cover Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism and espouse Buddhist principles (e.g. upholding dhamma and ahimsa).

The Ashokan Prakrit dialects reflected local forms of the Early Middle-Indo-Aryan language. Three dialect areas are represented: Northwestern, Western, and Eastern. The Central dialect of Indo-Aryan is exceptionally not represented; instead, inscriptions of that area use the Eastern forms. [2]:50[1] Ashokan Prakrit is descended from an Old Indo-Aryan dialect closely related to Vedic Sanskrit, on occasion diverging by preserving archaisms from Proto-Indo-Aryan.

Ashokan Prakrit is attested in the Dhammalipi and the Kharoshthi script (only in the Northwest).

Classification

Masica classifies Ashokan Prakrit as an Early Middle-Indo-Aryan language, representing the earliest stage after Old Indo-Aryan in the historical development of Indo-Aryan.[2]:52

Dialects

There are three dialect groups attested in the Ashokan Edicts, based on phonological and grammatical idiosyncrasies which correspond with developments in later Middle Indo-Aryan languages:[3][4][5]

- Western: The inscriptions at Girnar and Sopara, which: prefer r over l; do not merge the nasal consonants (n, ñ, ṇ); merge all sibilants into s; prefer (c)ch as the reflex of the Old Indo-Aryan thorn cluster kṣ; have -o as the nominative singular of masculine a-stems, among other morphological peculiarities. Notably, this dialect corresponds well with Pali, the preferred Middle Indo-Aryan language of Buddhism.[6]:5

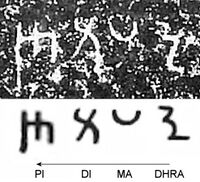

- Northwestern: The inscriptions at Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra written in the Kharosthi script: retain etymological r and l as distinct; do not merge the nasals; do not merge the sibilants (s, ś, ṣ); metathesis of liquids in consonant clusters (e.g. Sanskrit dharma > Shahbazgarhi dhrama). These features are shared with the modern Dardic languages.[7]

- Eastern: The standard administrative language, exemplified by the inscriptions at Dhauli and Jaugada and used in the geographical core of the Mauryan Empire: prefer l over r, merge the nasals into n (and geminate ṁn), prefer (k)kh as the reflex of OIA kṣ, have -e as the nominative singular of masculine a-stems, etc. Oberlies suggests that the inscriptions in the Central zone were translated from the "official" administrative forms of the Edicts.

Sample

The following is the first sentence of the Major Rock Edict 1, inscribed c. 257 BCE in many locations.[8]

- Girnar:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

- Kalsi:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

- Shahbazgarhi:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

- Mansehra:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

- Dhauli:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

- Jaugada:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

The dialect groups and their differences are apparent: the Northwest retains clusters but does metathesis on liquids (dhrama vs. other dhaṃma) and retains an earlier form dipi "writing" borrowed from Iranian.[9] Meanwhile, the l ~ r distinctions are apparent in the word for "king" (Girnar rāña but Jaugada lājinā).

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Thomas Oberlies. "Aśokan Prakrit and Pali". in George Cardona. The Indo-Aryan Languages. pp. 179–224.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Masica, Colin (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=J3RSHWePhXwC.

- ↑ Jules Bloch (1950) (in French). Les inscriptions d'Aśoka, traduites et commentées par Jules Bloch.

- ↑ Ashwini Deo (2018). "Dialects in the Indo-Aryan landscape". in Charles Boberg. The Handbook of Dialectology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/6/37654/files/2015/09/handbookdialectology-original-2akgf2w.pdf.

- ↑ Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (2007-07-26). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 165.

- ↑ Norman, Kenneth Roy (1983) (in English). Pali Literature. Wiesbaden: Otto Harrassowitz. pp. 2–3. ISBN 3-447-02285-X.

- ↑ George A. Grierson (1927). "On the Old North-Western Prakrit". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 4 (4): 849–852. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25221256.

- ↑ "2. Girnār, Kālsī, Shāhbāzgaṛhī, Mānsehrā, Dhauli, Jaugaḍa rock edicts (Synoptic, Māgadhī and English)". Bibliotheca Polyglotta. University of Oslo. https://www2.hf.uio.no/polyglotta/index.php?page=record&vid=365&mid=634949.

- ↑ Hultzsch, E. (1925). Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum v. 1: Inscriptions of Asoka. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. xlii. https://archive.org/stream/InscriptionsOfAsoka.NewEditionByE.Hultzsch/HultzschCorpusAsokaSearchable#page/n44/mode/1up.

|