Finance:Capitol Hill Babysitting Co-op

The Capitol Hill Babysitting Cooperative (CHBC) is a cooperative located in Washington, D.C., whose purpose is to fairly distribute the responsibility of babysitting between its members. The co-op is often used as an allegory for a demand-oriented model of an economy. The allegory illustrates several economic concepts, including the paradox of thrift and the importance of the money supply to an economy's well-being. The allegory has received continuing attention, particularly in the wake of the late-2000s recession.

Former members Joan Sweeney and Richard James Sweeney first presented the co-op as an allegory for an economy in a 1977 article, but it was little known until popularized by Paul Krugman in his book Peddling Prosperity and subsequent writings. Krugman has described the allegory as "a favorite parable"[1] and "life-changing".[2]

History

The co-op was founded in the late 1950s,[3] and (As of 2017) continues to operate.[4] In 2010, there were twenty families in the co-op (down from its heyday of 250 families). Some of these are second-generation members of the co-op. It is open to new members.

Members naturally left the co-op as their children grew up, but many continued to work together in various organizations. In 2007, a number of the now elderly former co-op members from the 1960s and 1970s were involved in founding the Capitol Hill Village, an organization dedicated to helping elderly people continue living at home by providing a support community.[5][6] The organization is modeled after Beacon Hill Village in Beacon Hill, Boston, and while it involves elements of mutualism, it is dues-paying and involves external parties.

Some additional details:[7]

- The co-op grew from 20 families in the early 1960s to more than 200 in the early 1970s.

- By the early 1970s the co-op was geographically split in two—north/south or east/west.

- In the 1960s the position of secretary rotated monthly. This was seen as an onerous task, which is why it was rotated, and entailed taking babysitting requests, matching sitters with requests (hence being on call at all times), and balancing the books.

- Double time was paid after midnight and between 5 pm and 7 pm (during supper time).[note 1]

- Time-and-a-half was paid for later hours.[3]

- The currency issued by the co-op, called scrip, was in extremely high demand, at least at some points,[3] with a former member being quoted as saying "Oh my God, you would kill for scrip. ... You would sell your children for scrip."

Cooperative system and history

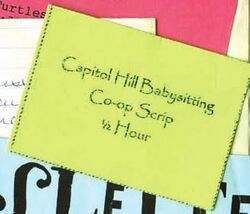

The co-op gave each new member twenty hours' worth of "scrip," and required them to return the same amount when they left the co-op.[note 2] Members of the co-op used scrip to pay for babysitting. Each piece of scrip was contractually deemed to pay for half an hour of babysitting. To earn more scrip, couples babysat other member's children. Administrators in the co-op were responsible for various tasks, such as matching couples needing a babysitter with couples that wanted to babysit. To "pay" for the administrative costs of the system, each member had an obligation to contribute fourteen hours' worth of scrip a year (i.e. 28 scrip). Some of the administration's scrip went to administrators to be spent and some was simply saved.[8]

At first, new members of the co-op felt, on average, that they should save more scrip before they began spending. So they babysat whenever the opportunity arose, but did not spend the scrip they acquired. Since babysitting opportunities only arise when other couples want to go out, there was a shortage of demand for babysitting.[8] As a result, the co-op fell into a "recession".[9] This illustrates the phenomenon known as the paradox of thrift.

The administration's initial reaction to the co-op's recession was to add new rules. But the measures did not resolve the inadequate demand for babysitting. Eventually, the co-op was able to alleviate the issue by giving new members thirty hours' worth of scrip, but only requiring them to return twenty when they left the co-op.[8][9]

Within a few years a new problem arose. There was too much scrip and a shortage of babysitting. As new members joined, more scrip was added to the system until couples had too much, but new members were not able to spend it because no one else wanted to babysit. In general, the cooperative experienced regular problems because the administration took in more than it spent, and at times the system added too much scrip into the system via the amount issued to new members.[8]

Hypothetical resolutions

The co-op's problems occurred because of two issues: the scrip's value was fixed, and the ratio of scrip to couples was volatile. The cooperative could have made the ratio of scrip to couples fixed, by adjusting the amount of scrip entering the system via new members and leaving the system via couples choosing to leave the co-op. In addition, it could have let the scrip value adjust so that couples were paid more scrip to babysit when the supply of babysitters was small, and less when the supply was large.[8]

Mitchell criticizes the suggestion that price flexibility alone would resolve the demand problem. He notes that a fall in prices would reduce the price of babysitting. This, of course, also means that the amount of scrip received for babysitting would also be less. Thus, since parents made less money, even as the supply of babysitters decreased, because of less incentive to babysit, the babysitters would not become wealthier.[10]

The traditional neo-classical response to this criticism, given by Pigou, is that the effect of cheaper babysitting prices is rather a redistribution of wealth from couples with little scrip to those with more, which will encourage persons who have saved in the past to spend more.

Mitchell criticizes this because, he asserts, the falling wages of babysitters only solves the problem if it reduces the desire of couples to save, which is not supported by any research.[10] The only effect of falling wages would be to increase the real value of nominal contracts. In other words, couples would have to spend more time babysitting before they acquired the amount necessary to leave the cooperative. Mitchell concludes that the problem is greater aggregate desire to save than can be funded by existing administrative debt, and that the solution is thus either to reduce (desire for) savings or, more likely increase spending by simply issuing more scrip.

Allegory for a liquidity trap

A modification to the co-op allegory creates a situation resembling a liquidity trap. Suppose that the co-op developed a system where parents were able to borrow scrip from the administration in emergencies and pay it back with interest later.[9]

This lending program would be advantageous to both the administration and parents. It gives the administration more tools to control demand for babysitting. If the administration observes that demand for babysitting is up, it can increase the interest members must pay when they borrow scrip, which will most likely result in less member borrowing. Thus the demand for babysitting will be reduced. Similarly, the administration can decrease the amount of interest paid when demand for babysitting is low. And the system would help parents, because they would no longer have to save as much scrip because they could simply borrow more in the cases of an emergency.[9]

These hypothetical modification to the Capitol Hill Babysitting Co-op makes its administration analogous to a central bank. Depending upon the economic conditions, the efficacy of the general system (i.e. the co-op) is partially dependent on interest rates. When times are good, it is best to have relatively high interest rates, and when times are bad the rates should be lower.[9]

Imagine that during the winter couples do not want to go out, but want to acquire more scrip for the summer. To compensate, the administration can lower the amount of extra scrip returned when parents want to borrow in the winter, and increase rates in the summer. Depending upon the strength of the seasonality of babysitting, this might work. But suppose the seasonality is so strong that no one wants to go out in the winter even when the administration sets its interest rates to zero. That is, suppose no parents want to go out even when they can borrow money for free. In this hypothetical situation, the co-op has fallen into a liquidity trap.[9]

Hypothetical resolutions

According to Krugman, the key problem is that the scrip's value is fixed. Couples know that each scrip they save in the winter can be redeemed for the same amount of time in the summer, giving them incentive to save because, psychologically speaking, each scrip's value is worth more to them in the summer than in the winter. Instead, if the co-op modified the system so that the scrip is redeemable for less time in the upcoming summer than in the winter, there would be less incentive to save because members would get less "bang for their buck" if they chose to hold onto the scrip until the summer. In other words, Krugman is suggesting that the co-op should have an inflationary monetary policy.[9]

The most common criticism of Krugman's interpretation, given by Austrian economics (see Austrian critiques) is that the problem is the fixed price of babysitting (wages), not of the scrip (money), alleging that the correct solution is to let couples decide how much they charge for babysitting on their own; when there is high demand or low supply of babysitters, couples would be more willing to babysit if they were given more scrip for their services.

Alternatively, the Neo-Chartalist view asserts that the co-op's administration should resolve the co-op's issues via "fiscal" policy.[10] That is, the scrip system is fiat money,[note 3] which can be created or destroyed at will by "spending" or "taxation", and the administration should simply inject more scrip into the system when demand is low, and reduce the amount of scrip when demand is high by increasing scrip fees or charging a levy (a "tax"). The co-op board's deficit spending (e.g. spending/issuing thirty, taxing twenty) is properly called fiscal policy, and should not be confused with monetary policy, which refers to central bank lending.

From the Chartalist perspective, the key point is the co-op board's deficits give co-op members additional scrip. This is because the co-op is a closed economy; assuming that there is a fixed amount of scrip, total savings is zero, so [math]\displaystyle{ S_g+S_m=0 }[/math] where [math]\displaystyle{ S_g }[/math] is the administration's savings and [math]\displaystyle{ S_m }[/math] is aggregate member savings. In other words, [math]\displaystyle{ S_m=-S_g }[/math]. Thus, as the administration's savings become negative [math]\displaystyle{ S_m }[/math] goes up. Initially when the administration spent twenty hours' worth of scrip and taxed twenty, there was no administrative debt (i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ S_g=0 }[/math]), which implies [math]\displaystyle{ S_m=0 }[/math]. The deficit spending created government debt of ten hours per family. Since every piece of scrip spent by the administration is given to the members, the result is that couples were given an additional ten hours of scrip (i.e. [math]\displaystyle{ S_m=-S_g=- }[/math][–10×(number of members)]=10×(number of members)), which may fulfill the private sector's desired savings quota.

The emphasis on the net scrip of co-op members, which equal the amount injected into the co-op by the administration, is the distinguishing feature of the Chartalist view. From this perspective, the function of introducing lending, as Krugman suggests, is that interest on this lending creates or destroys net member savings. For example, if the administration lends ten hours' worth of scrip at 10% interest for one year (thus collecting eleven hours' worth of scrip in one year's time), then it has created ten hours' worth of scrip but will withdraw eleven hours in the future, thus reducing net private sector assets by one hour.

As a consequence of this difference, while Krugman suggests using monetary policy to manage the economy, and resolving a liquidity trap by creating inflationary expectations to make saving less desirable,[9] Miller suggests using fiscal policy to manage the economy (matching administrative debt to desired private savings), and resolving a liquidity trap by issuing more scrip, hence increasing the administrative debt, to fund this desired saving.

Another proposed solution[according to whom?] is to put a maturity date upon the scrip, so that it must be spent, and people can borrow scrip through scrip "bonds".

Notes

- ↑ (Driscoll 2006) does not specify if double time was paid to sitters or to the secretary; (Cavanaugh 2008) states "time-and-a-half for later hours" for sitters.

- ↑ Some sources, such as (Cavanaugh 2008), state that the money was paid back after one year, which appears to be a misunderstanding, as (Sweeney Sweeney) specifies that it was paid back when a family left.

- ↑ Define fiat money to be money whose value is derived entirely from its official status as a means of exchange. Some alternative definitions also require that fiat money has no fixed value in terms of an objective standard. Under the latter definition the scrip is considered credit money.

References

- ↑ (Krugman 2001), (Krugman 2009)

- ↑ (Krugman 1998)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 (Cavanaugh 2008)

- ↑ Paul Krugman [@paulkrugman] (Dec 19, 2017). "Slate has reposted my old piece on monetary economics as illustrated by the Capitol Hill Babysitting Co-op (which is still in existence!)". https://twitter.com/paulkrugman/status/943113545855721472.

- ↑ Festa, Elizabeth (March 10, 2007), "A Village For the Elders: Neighbors' Plan Allows For Aging Without Moving", The Washington Post: F01, http://www.capitolhillvillage.org/articles/village.html, retrieved April 1, 2010

- ↑ Gray, Joshua (March 27, 2009), "Always at home", The Voice of the Hill, http://www.voiceofthehill.com/IN-YOUR-NEIGHBORHOOD/Always-at-home[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ (Driscoll 2006)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Sweeney, Joan and Richard J.. "Monetary Theory and the Great Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-op Crisis". http://cda.morris.umn.edu/~kildegac/Courses/M&B/Sweeney%20&%20Sweeney.pdf.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Krugman, Paul R. (14 August 1998). "Baby-Sitting the Economy: The baby-sitting co-op that went bust teaches us something that could save the world.". http://www.slate.com/id/1937.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 (Mitchell 2009)

- Sweeney, J.; Sweeney, R. J. (1977). "Monetary Theory and the Great Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-op Crisis: Comment". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 9 (1): 86–89. doi:10.2307/1992001. http://www.eecs.harvard.edu/cs286r/courses/fall09/papers/coop.pdf.

Co-op

- Driscoll, Pat Taffe (January 19–20, 2006), Interview with Pat Taffe Driscoll, http://www.capitolhillhistory.org/interviews/2006/driscoll_pat.html, retrieved April 1, 2010; the Driscolls were the 24th couple to join, and this interview discusses the co-op in the 1960s.

- Cavanaugh, Monica (April 2008), "The Capitol Hill Babysitting Coop: Celebrating its 50th Year of Community Childcare", Hill Rag: 118–119, http://www.capitalcommunitynews.com/publications/hillrag/2008_April/118-119_RAG_0408.pdf, retrieved 2010-03-27

Krugman

- Krugman, Paul (March 1994), Peddling Prosperity: Economic Sense and Nonsense in the Age of Diminished Expectations, W. W. Norton & Company, pp. 28–31 (The Attack on Keynes: Infantile Keynesianism) and 92–93 (The Supply-Siders), ISBN 978-0-393-03602-2

Austrian critiques

(All these references associated with the Ludwig von Mises Institute.)

- Ritenour, Shawn (Spring 2000), "Post-Modern Economics: The Return of Depression Economics by Paul Krugman", Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 3 (1), http://mises.org/journals/qjae/pdf/qjae3_1_9.pdf; critical review of (Krugman 1999b)

- Gordon, David (Jan 12, 2009), Krugman's Nanny State, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/krugmans-nanny-state/; critical review of (Krugman 2008b).

- Rallo, Juan Ramón (March 16, 2009) (in es), Krugman y su economía de los canguros keynesianos, http://juandemariana.org/comentario/3330/krugman/economia/canguros/keynesianos/

- Lora, Manuel (March 27, 2009), Krugman and His Economics of Keynesian Baby-Sitting, http://archive.mises.org/9699/krugman-and-his-economics-of-keynesian-baby-sitting/, retrieved February 5, 2014; translation of (Rallo 2009)

Alternative interpretations

- Template:Cite SSRN; interprets via the C-M-C' theory of Karl Marx and connects to the earlier Keynes of A Treatise on Money, rather than the later Keynes of The General Theory.

- Mitchell, Bill (August 23, 2009), A baby-sitting economy …, http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=4527

Other economics

- Kash, Ian A.; Friedman, Eric J.; Halpern, Joseph Y. (2007). "Optimizing scrip systems: efficiency, crashes, hoarders, and altruists". San Diego, California, USA: ACM. pp. 305–315. doi:10.1145/1250910.1250955. ISBN 978-1-59593-653-0. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=1250910.1250955. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- Hens, Thorsten; Schenk-Hoppe, Klaus Reiner; Vogt, Bodo (2003). "On the Micro-Foundations of Money: The Capitol Hill Baby-Sitting Co-op". Hamburg Institute of International Economics. http://ideas.repec.org/p/ags/hiiedp/26320.html. Retrieved 2010-04-01.

- Hens, T.; Schenk-Hoppé, K. R.; Vogt, B. (2007). "The Great Capitol Hill Baby Sitting Co-op: Anecdote or Evidence for the Optimum Quantity of Money?". Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 39 (6): 1305–1333. doi:10.1111/j.1538-4616.2007.00068.x.

External links

|