Finance:War finance

War finance is a branch of defense economics. The power of a military depends on its economic base and without this financial support, soldiers will not be paid, weapons and equipment cannot be manufactured and food cannot be bought. Hence, victory in war involves not only success on the battlefield but also the economic power and economic stability of a state. War finance covers a wide variety of financial measures including fiscal and monetary initiatives used in order to fund the costly expenditure of a war.[1]

War finance measures can be broadly classified into three main categories:

- levy of taxation

- raising of debts - borrowing

- creation of fresh money supply - inflation

Thus these measures may include levy of specific taxation, increase and enlarging the scope of existing taxation, raising of compulsory and voluntary loans from the public, arranging loans from foreign sovereign states or financial institutions, and also the creation of money by the government or the central banking authority.

Throughout the history of human civilization, from ancient times until the modern era, conflicts and wars have always involved the raising of resources and war finance has since remained, in some form or the other, a major part of any defense economy plan. For example, economics played a key role in the Roman Empire. The brutal wars between the Roman empire and the Carthage proved to be very costly so much that Rome even ran out of money altogether at one stage. The Roman economy during this period were a pre-industrial economy which meant the majority of workers up to 80% of them were involved in the area of agriculture. Virtually all the taxes that would be collected by the government were spent on the military operations which turned out to be about also 80% of the entire budget in c. 150. Due to the huge financial burden that the maintenance of the military operations would have on the economy, techniques were thought up to help solve the burden. One such technique was the process of debasing the coinage. This was used in many countries that used coins from precious metals and they would debase the coins. This however didn't last very long as inflation started to increase. Various governments in charge attempted to curb the high cost of inflation through new reforms but some of their attempts just got steadily worse with the increasing bureaucracy that the government had to maintain as well as the huge amounts spent on welfare payments to the growing population worse.[2]

Loot and plunder - or at least the prospect of such - may play a role in war economies.[3][4] This involves the taking of goods by force as part of a military or political victory and was used as a significant source of a revenue for the victorious state. During the first World War when the Germans occupied the Belgians, the Belgian factories were forced to produce goods for the German effort or dismantled their machinery and took it back to Germany – along with thousands and thousands of Belgian slave factory workers.

Taxation

Taxation can be one of the more politically contentious ways to finance war. Raising taxes is often domestically unpopular, as people know that higher taxes reduce their individual abilities to invest and consume. As a consequence, raising taxes on a tax-averse population in order to fund a war might result in widespread anti-war sentiment. Moreover, taxes confiscate a part of the labor and the capital of the population.[5] During World War I, the United States and Great Britain each financed one quarter of their war costs via increased taxation, while in Austria the contribution of taxation towards the expenditure was zero. [3] The British government felt that they were an exception to this general rule and they saw their wealth and financial stability as one of their strongest warfighting assets. The income tax was therefore increased from 5.8% in 1913 to just over 30% in 5 years in 1918. The threshold was reduced in order for millions more people to be liable to pay the income tax.

Borrowing

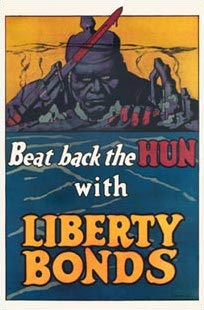

For the government another solution to finance war is for the government to increase its debt. When the Great War began, the majority of countries assumed that the war would be short especially in the eyes of the most powerful ally countries United States, Great Britain and France. They saw no need to raise taxes as it would have been politically difficult. It turned out however that it came at an extraordinary financial expense and as such thought it was best to pay for it by borrowing money and could thus transfer the war costs to future generations. The government can issue bonds that are bought by creditors, usually the Central Banks. The sacrifices are as a result differed, the government would need in the future to pay it back with some interests. There are many examples in war history, referred to as War bond. The economic consequences of this method of finance is less direct for the population, but equally important. The interests paid can be seen as pure wealth redistribution. Moreover, an accumulation of debt, which is too important, can affect the economy of a country, through its ability of refunding its debt. It can alter the confidence of people in the country's economy.[5] The war bonds were debt securities that would be issued by the government to finance the military operations and defense mechanisms during the time of a war. In practice, war can be financed through the creation of a fresh money supply adding additional money to the financial system and the function of these bonds were to help to control the increase of inflation and to keep it stable. The United States government during World War 1 spent over $300 million which converts to over $4 billion in today's financial market. People would then buy these bonds which looked like stamps for 10 or 15 cents each from the government and the government promised to return them with an interest after a period of 10 years or more. During a war especially during World War 1, governments needed all the extra money they could get their hands on to help pay for the war equipment and supplies. The advertisement of these bonds were carried out through many media outlets and through propaganda materials on radio, cinema adverts and newspapers in order to convince the large multitude of the countries population.[6]

Inflation

The government can also use a monetary tool to finance war, it could print more money in order to pay for troops, military complex and arms. But inflation is created, which reduces the purchasing power of people and can be thus seen as a form of taxation. However, it distributes the war costs in an arbitrary manner, especially on people with fixed incomes. At some point, such inflation could even reduce the production level of a country.[5] During the great war, countries decided to turn on the printing presses with almost every country abandoning the gold standard in 1914 and started to inflate their individual currencies by printing more banknotes. E.g., in Britain money supply was multiplied by almost 1151% and 1141% in Germany. Much of the extra money supply was absorbed by the war loans fortunate for the western countries while rationing out the controlled prices.

Borrowing vs. Taxing

When a conflict leads to higher governmental expenditures, the population financing the war is either paying directly (and immediately) or indirectly (and maybe delayed). Hence, war finance is can be divided into two categories: Direct or indirect financing. The former comprises taxes through which the population bears directly the burden, the latter includes borrowing or increasing the money supply. Empirical studies have established a connection between a leader's tax policy and subsequent punitive electoral consequences as they represent a permanent transfer of purchasing power by the taxpayer to the government.[7]

From a political perspective, borrowing is a more convenient way to finance wars because it can minimize the potential electoral consequences. Levying higher tax rates has an immediate effect on the population, whereas borrowing goes along with delayed repercussions. The advantage of borrowing is that it likely transfers the financial burden to a future government and consequently does not affect the current leader's prospects of a potential re-election. Second, borrowing itself is an accepted tool for the state to carry out its duties such as exerting expansive fiscal policies. That means because borrowing affects people only indirectly and is an accepted measure in general, it makes war a more diffuse target for critics, because it will be just one of the government's numerous debt sources. Of course, borrowing contributes to the increase of debt that causes also contentious debates. But particularly in the case of the United States, it can be observed that the hazard of a government shutdown is politically an undesirable outcome, even for the opposition. Having no alternatives, the Congress invariably passes legislation to increase the debt ceiling. This certainty guarantees that borrowing minimalizes any political costs.

To conclude, wartime borrowing is politically advantageous relative to war taxation: It is just an - although often a significant one - additional source of debt, which blurs the traces of the initiator as the ultimate repayment takes place long after the leader who started the war has stepped down. These characteristics reduce the political costs for the current leader and causes borrowing to generally be more attractive and politically viable than introduction of war taxes.[8]

History of different perspectives on War finance in the US

Financing a war requires the government to seek for additional revenue sources because government expenditures increase significantly during war or when a war is about to break out. The consequences of policies that focus to secure enough income sources have tremendous impact on the economy and often go even beyond the war itself. The determinants of how to provide financial funds are therefore driven by political interests giving different parties the opportunity to conceptualize and secure certain fiscal interests of their core constituencies. In the United States, the Republicans and their predecessors - the Whigs and Federalists - favoured to impose taxes, when the taxation was introduced as an ad valorem tariff or excise tax. These tax modes favoured manufacturing and business interests, the Republican base.

The Democrats, however, traditionally tended to abstain from taxes because their support came from the South, a strong exporting region that would suffer from tariffs and excise taxes. With the constitutionality of income taxes in 1913, the Democrats advocated a progressive income tax due to the important role of labour in their political base. With the business sector being its main political base, the Republicans opposed higher income taxes, rather favouring less fiscal policy, including on war taxation. The high repercussions and redistribution effects of taxes lead to various political interests. Thus, different lobby groups formed trying to have determining influence on the tax mode, when political leaders tried to generate revenues from taxing or other alternatives. [8]

Case Study: War costs of Afghanistan and Iraq

Not surprisingly, instrumental politicians tend to avoid war taxes, especially when the reasonableness of a war is publicly challenged or when the real cost of a war a difficult to calculate. This was also confirmed in the case of the Afghanistan (2001) and Iraq (2003) war. Both wars were financed through heavy borrowing. In 2003, the Bush-Administration reckoning with a fast conquering expedition estimated the cost of the Iraq war at $50 billion to $60 billion.[9] This turned out to be a severe miscalculation, when it became clear that the conquering of Iraq was much more complicated and that stability of Iraq required a long-term engagement of the US military. Three years later, in February 2006, a working paper authored by economists Linda Bilmes and Joseph Stiglitz already believed the true cost to be more than one trillion dollars, taking a conservative approach and supposing a troop withdrawal by 2010, not even including costs borne by other countries.[10] A subsequent paper, published in March 2013, figured that the cost of the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts will be at least $4 trillion. However, taking into consideration macroeconomic costs such as higher oil prices would be likely to raise the cost to $5 or $6 trillion.[11]

References

- ↑ Rosella Cappella Zielinski, How states pay for wars (Cornell University Press, 2016) online.

- ↑ "Warfare and Financial History" (in en). http://projects.exeter.ac.uk/RDavies/arian/war.html.

- ↑ Capella Zielinski, Rosella (2016-07-01). How States Pay for Wars. Cornell University Press (published 2016). ISBN 9781501706516. https://books.google.com/books?id=JqXKDAAAQBAJ. Retrieved 2016-09-13. "When belligerents do resort to plunder, it only comprises a small percent of their war finance strategy. Only two states have financed more than 25 percent of their war by plunder, Germany during the First Schleswig-Holstein War and Chile during the Pacific War."

- ↑ Compare: Hall, Jonathan; Swain, Ashok (2008). "7: Catapulting Conflicts or Propelling Peace: Diasporas and Civil Wars". in Swain, Ashok; Amer, Ramses; Öjendal, Joakim. Globalization and Challenges to Building Peace. Anthem Studies in Peace, Conflict and Development Series. London: Anthem Press. p. 113. ISBN 9781843312871. https://books.google.com/books?id=cTXekQIjsLgC. Retrieved 2016-09-12. "In the post-cold war conflicts, the belligerents [...] aim not to resolve conflict, but rather to sustain it, to take advantage of economic opportunities afforded by looting, rent seeking, taxing or siphoning off humanitarian aid and remittances, and by illicit trade."

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 [1] by H.A. Scott Trask in: MisesInstitute Austrian Economics, freedom, and peace, "War Finance : Theory and History"

- ↑ Momoh, Osi (2003-11-18). "War Bond" (in en-US). Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/w/warbonds.asp#ixzz5E3dZHx00.

- ↑ Gilbert, Charles (1970). American Financing of World War I. Westport, CT: Greenwood Publishing.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Flores-Macias, Gustavo A.; Kreps, Sarah E. (2013). "Political Parties at War: A Study of American War Finance, 1789–2010". American Political Science Review 107 (November 2013): 833–835. doi:10.1017/S0003055413000476.

- ↑ Herszenhorn, David M. (2008-03-19). "Estimates of Iraq War Cost Were Not Close to Ballpark" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/19/washington/19cost.html.

- ↑ Bilmes, Linda; Stiglitz, Joseph E. (February 2006). "The Economic Costs of the Iraq War: An Appraisal Three Years After the Beginning of the Conflict". NBER Working Paper No. 12054. doi:10.3386/w12054.

- ↑ Bilmes, Linda J. (March 2013). "The Financial Legacy of Iraq and Afghanistan: How Wartime Spending Decisions Will Constrain Future National Security Budgets". HARVARD Kennedy School.

Further reading

- Ball, Douglas B. Financial Failure and Confederate Defeat (University of Illinois Press, 1991) online book review

- Barbieri, Katherine. The Liberal Illusion: Does Trade Promote Peace? (University of Michigan Press, 2002).

- Caverley, Jonathan D. "The economics of war and peace." The Oxford Handbook of International Security (2018): 304-318 doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198777854.013.20

- Chang, Chia-Chien. "Economic Inequality, War Finance and the Pursuit of Tax Fairness." Journal of Human Values 26.2 (2020): 114-132.

- Daunton, Martin J. "How to pay for the war: state, society and taxation in Britain, 1917–24." English Historical Review 111.443 (1996): 882-919. doi.org/10.1093/ehr/CXI.443.882

- Flores-Macías, Gustavo A., and Sarah E. Kreps. "Political parties at war: A study of American war finance, 1789–2010." American Political Science Review 107.4 (2013): 833-848. online

- Flores-Macías, Gustavo A., and Sarah E. Kreps. "Borrowing support for war: The effect of war finance on public attitudes toward conflict." Journal of Conflict Resolution 61.5 (2017): 997-1020. online

- Garriga, Ana Carolina. "Central banks and civil war termination." Journal of Peace Research 59.4 (2022): 508-525. online

- Gill, David James. The Long Shadow of Default: Britain's Unpaid War Debts to the United States, 1917-2020 (Yale University Press, 2022) [2].

- Goldstein, Joshua S. The real price of war: How you pay for the war on terror (NYU Press, 2005), focus on USA online

- Hall, George J., and Thomas J. Sargent. "Debt and taxes in eight US wars and two insurrections." in The Handbook of Historical Economics (Academic Press, 2021(. 825-880. online

- Kirss, Alexander. "Interest or ideology? Why American business leaders opposed the Vietnam War." Business and Politics 24.2 (2022): 171-187.

- Poast, Paul. "Beyond the 'sinew of war': The political economy of security as a subfield." Annual Review of Political Science 22 (2019): 223-239. online

- Poast, Paul. "Economics and War." in Understanding War and Peace (2023): 175+ online.

- Saylor, Ryan, and Nicholas C. Wheeler. "Paying for war and building states: The coalitional politics of debt servicing and tax institutions." World Politics 69.2 (2017): 366-408. On South America in 19th century.

- Shea, Patrick E. "Money Talks: Finance, War, and Great Power Politics in the Nineteenth Century." Social Science History 44.2 (2020): 223-249. [DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ssh.2020.3 online]

- Wilson, Peter H., and Marianne Klerk. "The business of war untangled: Cities as fiscal-military hubs in Europe (1530s–1860s)." War in History 29.1 (2022): 80-103. online

- Wolfson, Murray, and Robert Smith. "How not to pay for the war." Defence and Peace Economics 4.4 (1993): 299-314. doi.org/10.1080/10430719308404770 re Gulf War of 1991.

- Zielinski, Rosella Cappella. How states pay for wars (Cornell University Press, 2016) onlne.

External links

- Collection of documents relating to war finance available on FRASER

|