Strategic network formation

Strategic network formation defines how and why networks take particular forms. In many networks, the relation between nodes is determined by the choice of the participating players involved, not by an arbitrary rule. A "strategic2 modeling of network requires defining a network’s costs and benefits and predicts how individual preferences become outcomes.

Introduction

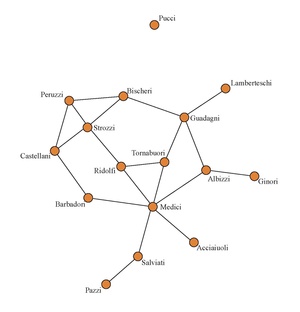

A strategic network formation requires that individuals create relations that are beneficial and drop those that are not. One of the most well-known examples in this context is the marriage network of sixteen families in Florence, which showed how the Medici family gained power and took control of Florence by creating a high number of inter-marriages with the other families.[1] “Thus, decisions about profitable relations are not a situation of choice, but a situation of strategic interaction – an aspect that is best covered by Game Theory”.[2]:2 In these kinds of settings, the nodes are usually called players, where [math]\displaystyle{ N = }[/math]{1, 2,… [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]} is a set of players that have formed links in a network. Social Networks have diverse settings, however the simplest ones can be described by an undirected graph whereas more complicated situations are represented by directed graphs.[3] There are fundamental differences in the way these games are modeled depending on their graph structure. If a link exists between player [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and player [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] it is noted as [math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math]. In cases of undirected networks, [math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math] is considered equal to [math]\displaystyle{ ji }[/math]. A network [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] represents a list of all the links between players. In a more formal setting, a network [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is defined as a set of unordered pairs {[math]\displaystyle{ i, j }[/math]}, with [math]\displaystyle{ i,j }[/math] element of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{N} }[/math].[2]:7The set of all possible graphs on the set of players [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math] is denoted with [math]\displaystyle{ G }[/math]. The benefits that they receive from the network are represented by utility functions. That is, the payoff to a player [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] is represented by a function [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math] : [math]\displaystyle{ G(N) }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \rightarrow }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R} }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]) represents the net benefit that i receives if network [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is in place.[3]:203 To model strategic network formation the notion of network games is used. A network game is a set of linked players and their utility functions.

Modeling network formation

Network games can be modeled in different ways. Some of the modeling methods that separate the utility allocation from the network formation process are extensive form games, simultaneous move games, and pairwise stability.

Extensive-form game modeling

If a network is modeled according to the extensive form game concept then the players of the network first propose to create links one after the other and afterwards they make decisions to create a link or not. In such settings, a couple of players decide to either form a link or not by being aware of all the previous players’ decisions and by making predictions for the decisions of the following players.

Simultaneous-move game modeling

In simultaneous move game settings, all the players declare at the same time to whom they want to link. Even though these sorts of games are easy to understand and analyze, their drawback is that they have multiple Nash equilibria.

Pairwise stability

In social networks, a link between two players is formed only if both of them decide to do so, however either of them can make the decision to delete a link without the other player’s approval. The concept of Nash equilibrium has a drawback in this case since it does not take into consideration the fact that the players can discuss their decisions. To model such a situation a stability concept that takes this fact into account is required. A useful stability concept in this case is Pairwise Stability, which accounts for the mutual approval of both players. A network is considered pairwise stable if:

(i) for all [math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math] ∈ [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ \ge }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]-[math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math]) and [math]\displaystyle{ u_j }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ \ge }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ u_j }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]-[math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math]), and

(ii) for all [math]\displaystyle{ ij }[/math] ∉ [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math], if [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g+ij }[/math]) > [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]) then [math]\displaystyle{ u_j }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g+ij }[/math]) < [math]\displaystyle{ u_j }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math])[3]:205

Therefore, a network in which there are no two players that want to create a link and where neither one of them wants to delete a link is pairwise-stable. Some of the drawbacks that make the prairwise-stability concept weak, are that it does not consider changes of multiple links at a time, but only looks at changes that happen between single links. The fact that it considers movements for only a couple of players at a given time can be considered as an additional weakness.

Network efficiency

There is a difference between networks that maximize the social welfare and networks that are based on personal incentives. In strategic network formation it is important to look at the overall social benefit and to see if networks that players create manage to be efficient for the society in general. A network [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is efficient relative to a profile of utility functions ([math]\displaystyle{ u_1 }[/math],..., [math]\displaystyle{ u_n }[/math]) if [math]\displaystyle{ \textstyle \sum_{i}u_i (g)\ge \textstyle \sum_{i} u_i (g') }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ g' \in G(N) }[/math].[3]:32

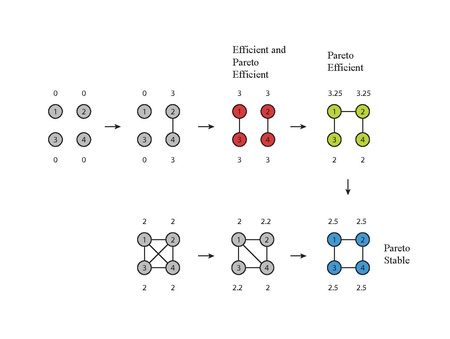

Pareto efficiency is another efficiency concept used by economists to study the overall social welfare. A network [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] is Pareto efficient relative to ([math]\displaystyle{ u_1 }[/math],... [math]\displaystyle{ u_n }[/math]) if there does not exist any [math]\displaystyle{ g' \in G }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g' }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ \ge }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ u_i }[/math]([math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math]) for all [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] with strict inequality for some [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math].[3]:206 The Pareto efficiency notion is more reasonable in settings in which allocation rules are fixed.[3]:32 A network can Pareto dominate another network if it has strictly larger benefits for one individual and weakly larger benefits for all individuals. If there exists a network which is not Pareto dominated by another network then it is a Pareto efficient network. In the figure "An Example of Efficient, Pareto Efficient, and Pairwise Stable Networks in a Four Person Society" an example with four players is given, where the payoffs of the players are noted by the numbers next to the nodes. If an arrow is pointing away from a network, it means that the network is not stable, since there would be benefit from deleting a link from a player or by creating a new link from two players of the network. The network in red is Efficient and Pareto efficient, since all the other link combinations offer lower payoffs to some of the players. The network in green is Pareto efficient since the payoffs are higher but it is not pairwise-stable because the players that have created only one link would also benefit by adding links to one another. The only Pairwise Stable network in the figure is the dark blue colored one since none of the players involved would benefit by deleting or creating a link.

Jackson and Wolinsky showed that for homogeneous connection cost, the efficient network can only take one of three forms: a complete graph, a star or an empty graph depending on connection cost and benefits. Finding general analytical solutions for the efficient networks with heterogeneous costs can be intractable. However, for particular cost structures, such as Island-connection[4] and separable heterogeneous connection costs,[5] the efficient network can identified based on the heterogeneous connection costs and benefits. For the latter the efficient network has "generalized star" structure.[5]

Distance-based utility

The utility the players receive does not just come from the direct links that they form with each other, but also from their indirect relations. The benefit function [math]\displaystyle{ b }[/math]: {1,… [math]\displaystyle{ n-1 }[/math]} [math]\displaystyle{ \rightarrow }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{R} }[/math] measures the indirect benefit that players obtain from being close to other players in the network. When we consider distance, the utility function takes the form

[math]\displaystyle{ u_i (g)= \sum_{j\ne i:j \in N^{n-1}(g)} b(l_{ij} (g))-d_i(g)c }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ l_{ij}(g) }[/math] represents the shortest path length between player [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and player [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math].[3]:209

The distance-based utility assumes that all players’ utility functions are alike and it takes into account only the benefits from indirect links that depend on minimum path length. These two features are considered as drawbacks of the distance-based utility.

Externalities

Externalities show that players’ benefits depend heavily on other players’ commitment decisions. The distance-based utility showed that the payoffs of players do not just depend on the direct links that they form, but also on the links that other players have created in the network. Players may confront positive or negative externalities in networks. The distance-based utility model is an example of positive externalities, since players can only get more benefits when other players increase their number of connections. On the other hand, a model that faces players with negative externalities is the so-called “Co-Author model” presented by Jackson and Wolinsky in the paper of 1996. Given that working on a research paper requires time and devotion, two researchers can benefit more if are only working with each other at a given period of time and not with many other people. Therefore, in the “Co-Author model” researchers benefit more if their other colleagues have fewer links. In this model, if a player’s neighbors have many links, it will bring negative externalities to them. In different models, positive or negative externalities lead to inefficiency.

References

- ↑ J.F, Padgett (1994). Marriage and Elite Structure in Renaissance Florence.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Buchel, Berno (2009). Advances in Strategic Network Formation: Preferences, Centrality, and Externalities. Bielefeld. ISBN 9783838112176. https://books.google.com/books?id=_GTfQgAACAAJ.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 O Jackson, Matthew (2003). A survey of models of network formation: Stability and Efficiency. Princeton University Press. http://www.stanford.edu/~jacksonm/netsurv.pdf.

- ↑ Jackson, Matthew; Brian W. Rogers (2005). "The Economics of Small Worlds". Journal of the European Economic Association 3 (2–3): 617–627. doi:10.1162/jeea.2005.3.2-3.617. https://authors.library.caltech.edu/4103/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Heydari, Babak; Mosleh, Mohsen; Dalili, Kia (2015). "Efficient network structures with separable heterogeneous connection costs". Economics Letters 134: 82–85. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2015.06.014.

|