Multiple-criteria decision analysis

Multiple-criteria decision-making (MCDM) or multiple-criteria decision analysis (MCDA) is a sub-discipline of operations research that explicitly evaluates multiple conflicting criteria in decision making (both in daily life and in settings such as business, government and medicine). Conflicting criteria are typical in evaluating options: cost or price is usually one of the main criteria, and some measure of quality is typically another criterion, easily in conflict with the cost. In purchasing a car, cost, comfort, safety, and fuel economy may be some of the main criteria we consider – it is unusual that the cheapest car is the most comfortable and the safest one. In portfolio management, managers are interested in getting high returns while simultaneously reducing risks; however, the stocks that have the potential of bringing high returns typically carry high risk of losing money. In a service industry, customer satisfaction and the cost of providing service are fundamental conflicting criteria.

In their daily lives, people usually weigh multiple criteria implicitly and may be comfortable with the consequences of such decisions that are made based on only intuition.[1] On the other hand, when stakes are high, it is important to properly structure the problem and explicitly evaluate multiple criteria.[2] In making the decision of whether to build a nuclear power plant or not, and where to build it, there are not only very complex issues involving multiple criteria, but there are also multiple parties who are deeply affected by the consequences.

Structuring complex problems well and considering multiple criteria explicitly leads to more informed and better decisions. There have been important advances in this field since the start of the modern multiple-criteria decision-making discipline in the early 1960s. A variety of approaches and methods, many implemented by specialized decision-making software,[3][4] have been developed for their application in an array of disciplines, ranging from politics and business to the environment and energy.[5]

Foundations, concepts, definitions

MCDM or MCDA are acronyms for multiple-criteria decision-making and multiple-criteria decision analysis. Stanley Zionts helped popularizing the acronym with his 1979 article "MCDM – If not a Roman Numeral, then What?", intended for an entrepreneurial audience.

MCDM is concerned with structuring and solving decision and planning problems involving multiple criteria. The purpose is to support decision-makers facing such problems. Typically, there does not exist a unique optimal solution for such problems and it is necessary to use decision-makers' preferences to differentiate between solutions.

"Solving" can be interpreted in different ways. It could correspond to choosing the "best" alternative from a set of available alternatives (where "best" can be interpreted as "the most preferred alternative" of a decision-maker). Another interpretation of "solving" could be choosing a small set of good alternatives, or grouping alternatives into different preference sets. An extreme interpretation could be to find all "efficient" or "nondominated" alternatives (which we will define shortly).

The difficulty of the problem originates from the presence of more than one criterion. There is no longer a unique optimal solution to an MCDM problem that can be obtained without incorporating preference information. The concept of an optimal solution is often replaced by the set of nondominated solutions. A solution is called nondominated if it is not possible to improve it in any criterion without sacrificing it in another. Therefore, it makes sense for the decision-maker to choose a solution from the nondominated set. Otherwise, she/he could do better in terms of some or all of the criteria, and not do worse in any of them. Generally, however, the set of nondominated solutions is too large to be presented to the decision-maker for the final choice. Hence we need tools that help the decision-maker focus on the preferred solutions (or alternatives). Normally one has to "tradeoff" certain criteria for others.

MCDM has been an active area of research since the 1970s. There are several MCDM-related organizations including the International Society on Multi-criteria Decision Making,[6] Euro Working Group on MCDA,[7] and INFORMS Section on MCDM.[8] For a history see: Köksalan, Wallenius and Zionts (2011).[9] MCDM draws upon knowledge in many fields including:

- Mathematics

- Decision analysis

- Economics

- Computer technology

- Software engineering

- Information systems

A typology

There are different classifications of MCDM problems and methods. A major distinction between MCDM problems is based on whether the solutions are explicitly or implicitly defined.

- Multiple-criteria evaluation problems: These problems consist of a finite number of alternatives, explicitly known in the beginning of the solution process. Each alternative is represented by its performance in multiple criteria. The problem may be defined as finding the best alternative for a decision-maker (DM), or finding a set of good alternatives. One may also be interested in "sorting" or "classifying" alternatives. Sorting refers to placing alternatives in a set of preference-ordered classes (such as assigning credit-ratings to countries), and classifying refers to assigning alternatives to non-ordered sets (such as diagnosing patients based on their symptoms). Some of the MCDM methods in this category have been studied in a comparative manner in the book by Triantaphyllou on this subject, 2000.[10]

- Multiple-criteria design problems (multiple objective mathematical programming problems): In these problems, the alternatives are not explicitly known. An alternative (solution) can be found by solving a mathematical model. The number of alternatives is either finite or infinite (countable or not countable), but typically exponentially large (in the number of variables ranging over finite domains.)

Whether it is an evaluation problem or a design problem, preference information of DMs is required in order to differentiate between solutions. The solution methods for MCDM problems are commonly classified based on the timing of preference information obtained from the DM.

There are methods that require the DM's preference information at the start of the process, transforming the problem into essentially a single criterion problem. These methods are said to operate by "prior articulation of preferences". Methods based on estimating a value function or using the concept of "outranking relations", analytical hierarchy process, and some rule-based decision methods try to solve multiple criteria evaluation problems utilizing prior articulation of preferences. Similarly, there are methods developed to solve multiple-criteria design problems using prior articulation of preferences by constructing a value function. Perhaps the most well-known of these methods is goal programming. Once the value function is constructed, the resulting single objective mathematical program is solved to obtain a preferred solution.

Some methods require preference information from the DM throughout the solution process. These are referred to as interactive methods or methods that require "progressive articulation of preferences". These methods have been well-developed for both the multiple criteria evaluation (see for example, Geoffrion, Dyer and Feinberg, 1972,[11] and Köksalan and Sagala, 1995[12] ) and design problems (see Steuer, 1986[13]).

Multiple-criteria design problems typically require the solution of a series of mathematical programming models in order to reveal implicitly defined solutions. For these problems, a representation or approximation of "efficient solutions" may also be of interest. This category is referred to as "posterior articulation of preferences", implying that the DM's involvement starts posterior to the explicit revelation of "interesting" solutions (see for example Karasakal and Köksalan, 2009[14]).

When the mathematical programming models contain integer variables, the design problems become harder to solve. Multiobjective Combinatorial Optimization (MOCO) constitutes a special category of such problems posing substantial computational difficulty (see Ehrgott and Gandibleux,[15] 2002, for a review).

Representations and definitions

The MCDM problem can be represented in the criterion space or the decision space. Alternatively, if different criteria are combined by a weighted linear function, it is also possible to represent the problem in the weight space. Below are the demonstrations of the criterion and weight spaces as well as some formal definitions.

Criterion space representation

Let us assume that we evaluate solutions in a specific problem situation using several criteria. Let us further assume that more is better in each criterion. Then, among all possible solutions, we are ideally interested in those solutions that perform well in all considered criteria. However, it is unlikely to have a single solution that performs well in all considered criteria. Typically, some solutions perform well in some criteria and some perform well in others. Finding a way of trading off between criteria is one of the main endeavors in the MCDM literature.

Mathematically, the MCDM problem corresponding to the above arguments can be represented as

- "max" q

- subject to

- q ∈ Q

where q is the vector of k criterion functions (objective functions) and Q is the feasible set, Q ⊆ Rk.

If Q is defined explicitly (by a set of alternatives), the resulting problem is called a multiple-criteria evaluation problem.

If Q is defined implicitly (by a set of constraints), the resulting problem is called a multiple-criteria design problem.

The quotation marks are used to indicate that the maximization of a vector is not a well-defined mathematical operation. This corresponds to the argument that we will have to find a way to resolve the trade-off between criteria (typically based on the preferences of a decision maker) when a solution that performs well in all criteria does not exist.

Decision space representation

The decision space corresponds to the set of possible decisions that are available to us. The criteria values will be consequences of the decisions we make. Hence, we can define a corresponding problem in the decision space. For example, in designing a product, we decide on the design parameters (decision variables) each of which affects the performance measures (criteria) with which we evaluate our product.

Mathematically, a multiple-criteria design problem can be represented in the decision space as follows:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \max q & = f(x) = f(x_1,\ldots,x_n) \\ \text{subject to} \\ q\in Q & = \{f(x) : x\in X,\, X\subseteq \mathbb R^n\} \end{align} }[/math]

where X is the feasible set and x is the decision variable vector of size n.

A well-developed special case is obtained when X is a polyhedron defined by linear inequalities and equalities. If all the objective functions are linear in terms of the decision variables, this variation leads to multiple objective linear programming (MOLP), an important subclass of MCDM problems.

There are several definitions that are central in MCDM. Two closely related definitions are those of nondominance (defined based on the criterion space representation) and efficiency (defined based on the decision variable representation).

Definition 1. q* ∈ Q is nondominated if there does not exist another q ∈ Q such that q ≥ q* and q ≠ q*.

Roughly speaking, a solution is nondominated so long as it is not inferior to any other available solution in all the considered criteria.

Definition 2. x* ∈ X is efficient if there does not exist another x ∈ X such that f(x) ≥ f(x*) and f(x) ≠ f(x*).

If an MCDM problem represents a decision situation well, then the most preferred solution of a DM has to be an efficient solution in the decision space, and its image is a nondominated point in the criterion space. Following definitions are also important.

Definition 3. q* ∈ Q is weakly nondominated if there does not exist another q ∈ Q such that q > q*.

Definition 4. x* ∈ X is weakly efficient if there does not exist another x ∈ X such that f(x) > f(x*).

Weakly nondominated points include all nondominated points and some special dominated points. The importance of these special dominated points comes from the fact that they commonly appear in practice and special care is necessary to distinguish them from nondominated points. If, for example, we maximize a single objective, we may end up with a weakly nondominated point that is dominated. The dominated points of the weakly nondominated set are located either on vertical or horizontal planes (hyperplanes) in the criterion space.

Ideal point: (in criterion space) represents the best (the maximum for maximization problems and the minimum for minimization problems) of each objective function and typically corresponds to an infeasible solution.

Nadir point: (in criterion space) represents the worst (the minimum for maximization problems and the maximum for minimization problems) of each objective function among the points in the nondominated set and is typically a dominated point.

The ideal point and the nadir point are useful to the DM to get the "feel" of the range of solutions (although it is not straightforward to find the nadir point for design problems having more than two criteria).

Illustrations of the decision and criterion spaces

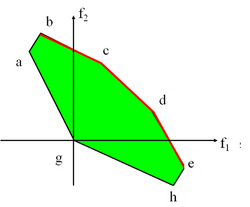

The following two-variable MOLP problem in the decision variable space will help demonstrate some of the key concepts graphically.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} \max f_1(\mathbf{x}) & = -x_1 + 2x_2 \\ \max f_2(\mathbf{x}) & = 2x_1 - x_2 \\ \text{subject to} \\ x_1 & \le 4 \\ x_2 & \le 4 \\ x_1+x_2 & \le 7 \\ -x_1+x_2 & \le 3 \\ x_1 - x_2 & \le 3 \\ x_1, x_2 & \ge 0 \end{align} }[/math]

In Figure 1, the extreme points "e" and "b" maximize the first and second objectives, respectively. The red boundary between those two extreme points represents the efficient set. It can be seen from the figure that, for any feasible solution outside the efficient set, it is possible to improve both objectives by some points on the efficient set. Conversely, for any point on the efficient set, it is not possible to improve both objectives by moving to any other feasible solution. At these solutions, one has to sacrifice from one of the objectives in order to improve the other objective.

Due to its simplicity, the above problem can be represented in criterion space by replacing the x's with the f 's as follows:

- Max f1

- Max f2

- subject to

- f1 + 2f2 ≤ 12

- 2f1 + f2 ≤ 12

- f1 + f2 ≤ 7

- f1 – f2 ≤ 9

- −f1 + f2 ≤ 9

- f1 + 2f2 ≥ 0

- 2f1 + f2 ≥ 0

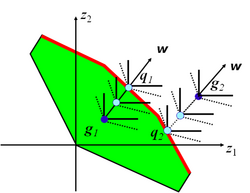

We present the criterion space graphically in Figure 2. It is easier to detect the nondominated points (corresponding to efficient solutions in the decision space) in the criterion space. The north-east region of the feasible space constitutes the set of nondominated points (for maximization problems).

Generating nondominated solutions

There are several ways to generate nondominated solutions. We will discuss two of these. The first approach can generate a special class of nondominated solutions whereas the second approach can generate any nondominated solution.

- Weighted sums (Gass & Saaty, 1955[16])

If we combine the multiple criteria into a single criterion by multiplying each criterion with a positive weight and summing up the weighted criteria, then the solution to the resulting single criterion problem is a special efficient solution. These special efficient solutions appear at corner points of the set of available solutions. Efficient solutions that are not at corner points have special characteristics and this method is not capable of finding such points. Mathematically, we can represent this situation as

- max wT.q = wT.f(x), w> 0

- subject to

- x ∈ X

By varying the weights, weighted sums can be used for generating efficient extreme point solutions for design problems, and supported (convex nondominated) points for evaluation problems.

- Achievement scalarizing function (Wierzbicki, 1980[17])

Achievement scalarizing functions also combine multiple criteria into a single criterion by weighting them in a very special way. They create rectangular contours going away from a reference point towards the available efficient solutions. This special structure empower achievement scalarizing functions to reach any efficient solution. This is a powerful property that makes these functions very useful for MCDM problems.

Mathematically, we can represent the corresponding problem as

- Min s(g, q, w, ρ) = Min {maxi [(gi − qi)/wi ] + ρ Σi (gi − qi)},

- subject to

- q ∈ Q

The achievement scalarizing function can be used to project any point (feasible or infeasible) on the efficient frontier. Any point (supported or not) can be reached. The second term in the objective function is required to avoid generating inefficient solutions. Figure 3 demonstrates how a feasible point, g1, and an infeasible point, g2, are projected onto the nondominated points, q1 and q2, respectively, along the direction w using an achievement scalarizing function. The dashed and solid contours correspond to the objective function contours with and without the second term of the objective function, respectively.

Solving MCDM problems

Different schools of thought have developed for solving MCDM problems (both of the design and evaluation type). For a bibliometric study showing their development over time, see Bragge, Korhonen, H. Wallenius and J. Wallenius [2010].[18]

Multiple objective mathematical programming school

(1) Vector maximization: The purpose of vector maximization is to approximate the nondominated set; originally developed for Multiple Objective Linear Programming problems (Evans and Steuer, 1973;[19] Yu and Zeleny, 1975[20]).

(2) Interactive programming: Phases of computation alternate with phases of decision-making (Benayoun et al., 1971;[21] Geoffrion, Dyer and Feinberg, 1972;[22] Zionts and Wallenius, 1976;[23] Korhonen and Wallenius, 1988[24]). No explicit knowledge of the DM's value function is assumed.

The purpose is to set apriori target values for goals, and to minimize weighted deviations from these goals. Both importance weights as well as lexicographic pre-emptive weights have been used (Charnes and Cooper, 1961[25]).

Fuzzy-set theorists

Fuzzy sets were introduced by Zadeh (1965)[26] as an extension of the classical notion of sets. This idea is used in many MCDM algorithms to model and solve fuzzy problems.

Ordinal data based methods

Ordinal data has a wide application in real-world situations. In this regard, some MCDM methods were designed to handle ordinal data as input data. For example, Ordinal Priority Approach and Qualiflex method.

Multi-attribute utility theorists

Multi-attribute utility or value functions are elicited and used to identify the most preferred alternative or to rank order the alternatives. Elaborate interview techniques, which exist for eliciting linear additive utility functions and multiplicative nonlinear utility functions, may be used (Keeney and Raiffa, 1976[27]). Another approach is to elicit value functions indirectly by asking the decision-maker a series of pairwise ranking questions involving choosing between hypothetical alternatives (PAPRIKA method; Hansen and Ombler, 2008[28]).

French school

The French school focuses on decision aiding, in particular the ELECTRE family of outranking methods that originated in France during the mid-1960s. The method was first proposed by Bernard Roy (Roy, 1968[29]).

Evolutionary multiobjective optimization school (EMO)

EMO algorithms start with an initial population, and update it by using processes designed to mimic natural survival-of-the-fittest principles and genetic variation operators to improve the average population from one generation to the next. The goal is to converge to a population of solutions which represent the nondominated set (Schaffer, 1984;[30] Srinivas and Deb, 1994[31]). More recently, there are efforts to incorporate preference information into the solution process of EMO algorithms (see Deb and Köksalan, 2010[32]).

Grey system theory based methods

In the 1980s, Deng Julong proposed Grey System Theory (GST) and its first multiple-attribute decision-making model, called Deng's Grey relational analysis (GRA) model. Later, the grey systems scholars proposed many GST based methods like Liu Sifeng's Absolute GRA model,[33] Grey Target Decision Making (GTDM)[34] and Grey Absolute Decision Analysis (GADA).[35]

Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

The AHP first decomposes the decision problem into a hierarchy of subproblems. Then the decision-maker evaluates the relative importance of its various elements by pairwise comparisons. The AHP converts these evaluations to numerical values (weights or priorities), which are used to calculate a score for each alternative (Saaty, 1980[36]). A consistency index measures the extent to which the decision-maker has been consistent in her responses. AHP is one of the more controversial techniques listed here, with some researchers in the MCDA community believing it to be flawed.[37][38] The underlying mathematics is also more complicated and requires rational analysis[vague],[38] though it has gained some popularity as a result of commercially available software.

Several papers reviewed the application of MCDM techniques in various disciplines such as fuzzy MCDM,[39] classic MCDM,[40] sustainable and renewable energy,[41] VIKOR technique,[42] transportation systems,[43] service quality,[44] TOPSIS method,[45] energy management problems,[46] e-learning,[47] tourism and hospitality,[48] SWARA and WASPAS methods.[49]

MCDM methods

The following MCDM methods are available, many of which are implemented by specialized decision-making software:[3][4]

- Aggregated Indices Randomization Method (AIRM)

- Analytic hierarchy process (AHP)

- Analytic network process (ANP)

- Balance Beam process

- Best worst method (BWM)[50][51]

- Brown–Gibson model

- Characteristic Objects METhod (COMET)[52][53]

- Choosing By Advantages (CBA)

- Conjoint Value Hierarchy (CVA)[54][55]

- Data envelopment analysis

- Decision EXpert (DEX)

- Disaggregation – Aggregation Approaches (UTA*, UTAII, UTADIS)

- Rough set (Rough set approach)

- Dominance-based rough set approach (DRSA)

- ELECTRE (Outranking)

- Evaluation Based on Distance from Average Solution (EDAS)[56]

- Evidential reasoning approach (ER)

- Goal programming (GP)

- Grey relational analysis (GRA)

- Inner product of vectors (IPV)

- Measuring Attractiveness by a categorical Based Evaluation Technique (MACBETH)

- Multi-Attribute Global Inference of Quality (MAGIQ)

- Multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT)

- Multi-attribute value theory (MAVT)

- Markovian Multi Criteria Decision Making

- New Approach to Appraisal (NATA)

- Nonstructural Fuzzy Decision Support System (NSFDSS)

- Ordinal Priority Approach (OPA)[57][58]

- Potentially All Pairwise RanKings of all possible Alternatives (PAPRIKA)

- PROMETHEE (Outranking)

- Simple Multi-Attribute Rating Technique (SMART) [59]

- Stratified Multi Criteria Decision Making (SMCDM)

- Stochastic Multicriteria Acceptability Analysis (SMAA)

- Superiority and inferiority ranking method (SIR method)

- System Redesigning to Creating Shared Value (SYRCS)[60]

- Technique for the Order of Prioritisation by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS)

- Value analysis (VA)

- Value engineering (VE)

- VIKOR method[61]

- Weighted product model (WPM)

- Weighted sum model (WSM)

See also

- Architecture tradeoff analysis method

- Decision-making

- Decision-making software

- Decision-making paradox

- Decisional balance sheet

- Multicriteria classification problems

- Rank reversals in decision-making

- Superiority and inferiority ranking method

References

- ↑ Rew, L. (1988). "Intuition in Decision-making". Journal of Nursing Scholarship 20 (3): 150–154. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.1988.tb00056.x. PMID 3169833.

- ↑ Franco, L.A.; Montibeller, G. (2010). "Problem structuring for multicriteria decision analysis interventions". Wiley Encyclopedia of Operations Research and Management Science. doi:10.1002/9780470400531.eorms0683. ISBN 9780470400531.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weistroffer, HR, and Li, Y (2016). "Multiple criteria decision analysis software". Ch 29 in: Greco, S, Ehrgott, M and Figueira, J, eds, Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: State of the Art Surveys Series, Springer: New York.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Amoyal, Justin (2018). "Decision analysis : Biennial survey demonstrates continuous advancement of vital tools for decision-makers, managers and analysts". OR/MS Today. doi:10.1287/orms.2018.05.13.

- ↑ Kylili, Angeliki; Christoforou, Elias; Fokaides, Paris A.; Polycarpou, Polycarpos (2016). "Multicriteria analysis for the selection of the most appropriate energy crops: The case of Cyprus". International Journal of Sustainable Energy 35 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1080/14786451.2014.898640. Bibcode: 2016IJSE...35...47K.

- ↑ "Multiple Criteria Decision Making – International Society on MCDM". http://www.mcdmsociety.org/.

- ↑ "Welcome to EWG-MCDA website". http://www.cs.put.poznan.pl/ewgmcda/.

- ↑ "Archived copy". http://www.informs.org/Community/MCDM/.

- ↑ Köksalan, M., Wallenius, J., and Zionts, S. (2011). Multiple Criteria Decision Making: From Early History to the 21st Century. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 9789814335591. https://books.google.com/books?id=LqAw1539l_cC.

- ↑ Triantaphyllou, E. (2000). Multi-Criteria Decision Making: A Comparative Study. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers (now Springer). p. 320. ISBN 978-0-7923-6607-2. http://www.csc.lsu.edu/trianta/Books/DecisionMaking1/Book1.htm.

- ↑ An Interactive Approach for Multi-Criterion Optimization, with an Application to the Operation of an Academic Department, A. M. Geoffrion, J. S. Dyer and A. Feinberg, Management Science, Vol. 19, No. 4, Application Series, Part 1 (Dec., 1972), pp. 357–368 Published by: INFORMS

- ↑ Köksalan, M.M. and Sagala, P.N.S., M. M.; Sagala, P. N. S. (1995). "Interactive Approaches for Discrete Alternative Multiple Criteria Decision Making with Monotone Utility Functions". Management Science 41 (7): 1158–1171. doi:10.1287/mnsc.41.7.1158.

- ↑ Steuer, R.E. (1986). Multiple Criteria Optimization: Theory, Computation and Application. New York: John Wiley.

- ↑ Karasakal, E. K. and Köksalan, M., E.; Koksalan, M. (2009). "Generating a Representative Subset of the Efficient Frontier in Multiple Criteria Decision Making". Operations Research 57: 187–199. doi:10.1287/opre.1080.0581.

- ↑ Ehrgott, M.; Gandibleux, X. (2002). Multiobjective Combinatorial Optimization. Multiple Criteria Optimization, State of the Art Annotated Bibliographic Surveys. pp. 369–444.

- ↑ Gass, S.; Saaty, T. (1955). "Parametric Objective Function Part II". Operations Research 2 (3): 316–319. doi:10.1287/opre.2.3.316.

- ↑ Wierzbicki, A. (1980). "The Use of Reference Objectives in Multiobjective Optimization". Multiple Criteria Decision Making Theory and Application. Springer, Berlin. 177. 468–486. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-48782-8_32. ISBN 978-3-540-09963-5.

- ↑ Bragge, J.; Korhonen, P.; Wallenius, H.; Wallenius, J. (2010). "Bibliometric Analysis of Multiple Criteria Decision Making/Multiattribute Utility Theory". Multiple Criteria Decision Making for Sustainable Energy and Transportation Systems. Springer, Berlin. 634. pp. 259–268. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-04045-0_22. ISBN 978-3-642-04044-3.

- ↑ Evans, J.; Steuer, R. (1973). "A Revised Simplex Method for Linear Multiple Objective Programs". Mathematical Programming 5: 54–72. doi:10.1007/BF01580111.

- ↑ Yu, P.L.; Zeleny, M. (1975). "The Set of All Non-Dominated Solutions in Linear Cases and a Multicriteria Simplex Method". Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications 49 (2): 430–468. doi:10.1016/0022-247X(75)90189-4.

- ↑ Benayoun, R.; deMontgolfier, J.; Tergny, J.; Larichev, O. (1971). "Linear Programming with Multiple Objective Functions: Step-method (STEM)". Mathematical Programming 1: 366–375. doi:10.1007/bf01584098.

- ↑ Geoffrion, A.; Dyer, J.; Feinberg, A. (1972). "An Interactive Approach for Multicriterion Optimization with an Application to the Operation of an Academic Department". Management Science 19 (4–Part–1): 357–368. doi:10.1287/mnsc.19.4.357.

- ↑ Zionts, S.; Wallenius, J. (1976). "An Interactive Programming Method for Solving the Multiple Criteria Problem". Management Science 22 (6): 652–663. doi:10.1287/mnsc.22.6.652.

- ↑ Korhonen, P.; Wallenius, J. (1988). "A Pareto Race". Naval Research Logistics 35 (6): 615–623. doi:10.1002/1520-6750(198812)35:6<615::AID-NAV3220350608>3.0.CO;2-K.

- ↑ Charnes, A. and Cooper, W.W. (1961). Management Models and Industrial Applications of Linear Programming. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Zadeh, L.A., Information and Control, Wikidata Q25938993

- ↑ Keeney, R.; Raiffa, H. (1976). Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Hansen, Paul; Ombler, Franz (2008). "A new method for scoring additive multi-attribute value models using pairwise rankings of alternatives". Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis 15 (3–4): 87–107. doi:10.1002/mcda.428.

- ↑ Roy, B. (1968). "La méthode ELECTRE". Revue d'Informatique et de Recherche Opérationelle (RIRO) 8: 57–75.

- ↑ Shaffer, J.D. (1984). Some Experiments in Machine Learning Using Vector Evaluated Genetic Algorithms, PhD thesis (phd). Nashville: Vanderbilt University.

- ↑ Srinivas, N.; Deb, K. (1994). "Multiobjective Optimization Using Nondominated Sorting in Genetic Algorithms". Evolutionary Computation 2 (3): 221–248. doi:10.1162/evco.1994.2.3.221.

- ↑ Deb, K.; Köksalan, M. (2010). "Guest Editorial Special Issue on Preference-Based Multiobjective Evolutionary Algorithms". IEEE Transactions on Evolutionary Computation 14 (5): 669–670. doi:10.1109/TEVC.2010.2070371.

- ↑ Liu, Sifeng (2017). Grey Data Analysis - Methods, Models and Applications. Singapore: Springer. pp. 67–104. ISBN 978-981-10-1841-1. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9789811018404.

- ↑ Liu, Sifeng (2013). "On Uniform Effect Measure Functions and a Weighted Multi-attribute Grey Target Decision Model". The Journal of Grey System (Research Information Ltd. (UK)) 25 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s40815-020-00827-8. http://www.researchinformation.co.uk/greyarchindex.php.

- ↑ Javed, S. A. (2020). "Grey Absolute Decision Analysis (GADA) Method for Multiple Criteria Group Decision-Making Under Uncertainty". International Journal of Fuzzy Systems (Springer) 22 (4): 1073–1090. doi:10.1007/s40815-020-00827-8.

- ↑ Saaty, T.L. (1980). The Analytic Hierarchy Process: Planning, Priority Setting, Resource Allocation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ Belton, V, and Stewart, TJ (2002). Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis: An Integrated Approach, Kluwer: Boston.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Munier, Nolberto (2021). Uses and limitations of the AHP method : a non-mathematical and rational analysis. Eloy Hontoria. Cham: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-60392-2. OCLC 1237399430. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1237399430.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Jusoh, Ahmad; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras (15 May 2015). "Fuzzy multiple criteria decision-making techniques and applications – Two decades review from 1994 to 2014". Expert Systems with Applications 42 (8): 4126–4148. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2015.01.003.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Jusoh, Ahmad; Nor, Khalil MD; Khalifah, Zainab; Zakwan, Norhayati; Valipour, Alireza (1 January 2015). "Multiple criteria decision-making techniques and their applications – a review of the literature from 2000 to 2014". Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja 28 (1): 516–571. doi:10.1080/1331677X.2015.1075139. ISSN 1331-677X. http://hrcak.srce.hr/file/253067.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Jusoh, Ahmad; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Cavallaro, Fausto; Khalifah, Zainab (19 October 2015). "Sustainable and Renewable Energy: An Overview of the Application of Multiple Criteria Decision Making Techniques and Approaches" (in en). Sustainability 7 (10): 13947–13984. doi:10.3390/su71013947.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Govindan, Kannan; Amat Senin, Aslan; Jusoh, Ahmad (4 January 2016). "VIKOR Technique: A Systematic Review of the State of the Art Literature on Methodologies and Applications" (in en). Sustainability 8 (1): 37. doi:10.3390/su8010037.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Khalifah, Zainab; Jusoh, Ahmad; Nor, Khalil MD (2 July 2016). "Multiple criteria decision-making techniques in transportation systems: a systematic review of the state of the art literature". Transport 31 (3): 359–385. doi:10.3846/16484142.2015.1121517. ISSN 1648-4142.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Jusoh, Ahmad; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Khalifah, Zainab; Nor, Khalil MD (3 September 2015). "Application of multiple-criteria decision-making techniques and approaches to evaluating of service quality: a systematic review of the literature". Journal of Business Economics and Management 16 (5): 1034–1068. doi:10.3846/16111699.2015.1095233. ISSN 1611-1699.

- ↑ Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Mardani, Abbas; Turskis, Zenonas; Jusoh, Ahmad; Nor, Khalil MD (1 May 2016). "Development of TOPSIS Method to Solve Complicated Decision-Making Problems — An Overview on Developments from 2000 to 2015". International Journal of Information Technology & Decision Making 15 (3): 645–682. doi:10.1142/S0219622016300019. ISSN 0219-6220.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Zavadskas, Edmundas Kazimieras; Khalifah, Zainab; Zakuan, Norhayati; Jusoh, Ahmad; Nor, Khalil Md; Khoshnoudi, Masoumeh (1 May 2017). "A review of multi-criteria decision-making applications to solve energy management problems: Two decades from 1995 to 2015". Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 71: 216–256. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.053.

- ↑ Zare, Mojtaba; Pahl, Christina; Rahnama, Hamed; Nilashi, Mehrbakhsh; Mardani, Abbas; Ibrahim, Othman; Ahmadi, Hossein (1 August 2016). "Multi-criteria decision making approach in E-learning: A systematic review and classification". Applied Soft Computing 45: 108–128. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2016.04.020.

- ↑ Diedonis, Antanas. "Transformations in Business & Economics – Vol. 15, No 1 (37), 2016 – Article". http://www.transformations.knf.vu.lt/37/article/appl.

- ↑ Mardani, Abbas; Nilashi, Mehrbakhsh; Zakuan, Norhayati; Loganathan, Nanthakumar; Soheilirad, Somayeh; Saman, Muhamad Zameri Mat; Ibrahim, Othman (1 August 2017). "A systematic review and meta-Analysis of SWARA and WASPAS methods: Theory and applications with recent fuzzy developments". Applied Soft Computing 57: 265–292. doi:10.1016/j.asoc.2017.03.045. https://zenodo.org/record/1041452.

- ↑ Rezaei, Jafar (2015). "Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method". Omega 53: 49–57. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2014.11.009.

- ↑ Rezaei, Jafar (2016). "Best-worst multi-criteria decision-making method: Some properties and a linear model". Omega 64: 126–130. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2015.12.001.

- ↑ Sałabun, W. (2015). The Characteristic Objects Method: A New Distance-based Approach to Multicriteria Decision-making Problems. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis, 22(1-2), 37-50.

- ↑ Sałabun, W., Piegat, A. (2016). Comparative analysis of MCDM methods for the assessment of mortality in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Artificial Intelligence Review. First Online: 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Garnett, H. M., Roos, G., & Pike, S. (2008, September). Reliable, Repeatable Assessment for Determining Value and Enhancing Efficiency and Effectiveness in Higher Education. OECD, Directorate for Education, Programme on Institutional Management in Higher Education [IMHE) Conference, Outcomes of Higher Education–Quality, Relevance and Impact.

- ↑ Millar, L. A., McCallum, J., & Burston, L. M. (2010). Use of the conjoint value hierarchy approach to measure the value of the national continence management strategy. Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal, The, 16(3), 81.

- ↑ Keshavarz Ghorabaee, M. et al. (2015) "Multi-Criteria Inventory Classification Using a New Method of Evaluation Based on Distance from Average Solution (EDAS) ", Informatica, 26(3), 435-451.

- ↑ Mahmoudi, Amin; Deng, Xiaopeng; Javed, Saad Ahmed; Zhang, Na (January 2021). "Sustainable Supplier Selection in Megaprojects: Grey Ordinal Priority Approach". Business Strategy and the Environment 30 (1): 318–339. doi:10.1002/bse.2623.

- ↑ Mahmoudi, Amin; Javed, Saad Ahmed; Mardani, Abbas (16 March 2021). "Gresilient supplier selection through Fuzzy Ordinal Priority Approach: decision-making in post-COVID era". Operations Management Research 15 (1–2): 208–232. doi:10.1007/s12063-021-00178-z.

- ↑ Edwards, W.; Baron, F.H. (1994). "Improved simple methods for multiattribute utility measurement". Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 60: 306–325. doi:10.1006/obhd.1994.1087.

- ↑ Khazaei, Moein; Ramezani, Mohammad; Padash, Amin; DeTombe, Dorien (2021-05-08). "Creating shared value to redesigning IT-service products using SYRCS; Diagnosing and tackling complex problems". Information Systems and E-Business Management 19 (3): 957–992. doi:10.1007/s10257-021-00525-4. ISSN 1617-9846. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10257-021-00525-4.

- ↑ Serafim, Opricovic; Gwo-Hshiung, Tzeng (2007). "Extended VIKOR Method in Comparison with Outranking Methods". European Journal of Operational Research 178 (2): 514–529. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2006.01.020.

Further reading

- Maliene, V. (2011). "Specialised property valuation: Multiple criteria decision analysis". Journal of Retail & Leisure Property 9 (5): 443–50. doi:10.1057/rlp.2011.7.

- "An assessment of sustainable housing affordability using a multiple criteria decision making method". Omega 41 (2): 270–79. 2013. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2012.05.002. http://eprints.maths.manchester.ac.uk/1906/1/mulliner13.pdf.

- Maliene, V. (2002). "Application of a new multiple criteria analysis method in the valuation of property". FIG XXII International Congress: 19–26. http://www.fig.net/pub/fig_2002/Ts9-3/TS9_3_maliene_etal.pdf.

- A Brief History prepared by Steuer and Zionts

- Malakooti, B. (2013). Operations and Production Systems with Multiple Objectives. John Wiley & Sons.

sr:Вишекритеријумска оптимизација

|