Organization:Survey of Palestine

The Survey of Palestine was the government department responsible for the survey and mapping of Palestine during the British mandate period.

The survey department was established in 1920 in Jaffa, and moved to the outskirts of Tel Aviv in 1931.[1] It established the Palestine grid.[2] In early 1948, the British Mandate appointed a temporary Director General of the Survey Department for the impending Jewish State; this became the Survey of Israel.[3]

The maps produced by the survey have been widely used in "Palestinian refugee cartography" by scholars documenting the 1948 Palestinian expulsion and flight;[4] notably in Salman Abu Sitta's Atlas of Palestine and Walid Khalidi's All That Remains.[4][5] In 2019 the maps were used as the basis for Palestine Open Maps, supported by the Bassel Khartabil Free Culture Fellowship.[6]

History

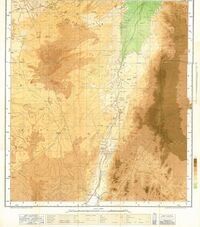

Prior to the beginning of the Mandate for Palestine, the British had carried out two significant surveys of the region: the PEF Survey of Palestine between 1872 and 1880, and a series of small-scale maps developed by General Allenby's Royal Engineers for the 1915–18 Sinai and Palestine campaign.[7][8] The Geographical Section of the War Office (G.S.G.S.), together with the Survey of Egypt, produced regional maps extending to Syria and Transjordan (scales 1:125,000, 1:250,000), copies of the PEF maps overprinted with revisions, and local maps, usually in the scale of 1:40,000.[9][10]

Immediately following the start of the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, the Zionist Organization began to pressure the British authorities to immediately begin the cadastral survey of the land, to facilitate Jewish land purchase in Palestine.[11][12] The Zionist Organization wanted to use the results of the survey work to identify land open for Jewish settlement and the strategies needed to acquire it, whether it was privately owned, state land or other types of land.[13] The Survey was initially resisted by the Palestinian Arab population, who considered it to be an attempt to sell their land from underneath them, given the differences between Ottoman land laws, customary land law and the new system which required "absolute proof of ownership".[11]

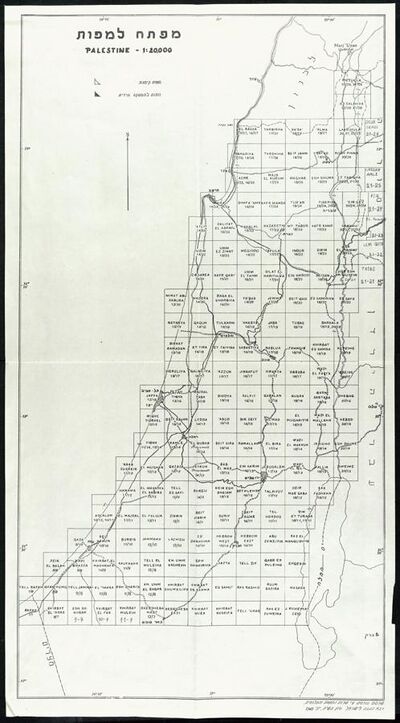

The national triangulation framework had been completed by 1930, consisting of 105 major points and c.20,000 lower-order points.[14][15] The 1:10,000 survey was completed in 1934, followed by the 1:2,500 property survey for Land Settlement; these surveys formed the basis for the published 1:20,000 and 1:100,000 topographical series.[14][16]

In 1940 the department no longer had responsibility for adjudicating land settlement claims, and began to focus fully on the survey work.[17] The February 1940 Land Transfer Regulations had divided Palestine into three regions with different restrictions on land sales applying to each. In Zone "A," which included the hill-country of Judea as a whole, certain areas in the Jaffa sub-District, and in the Gaza District, and the northern part of the Beersheba sub-District, new agreements for sale of land other than to a Palestinian Arab were forbidden without the High Commissioner's permission. In Zone "B," which included the Jezreel Valley, eastern Galilee, a parcel of coastal plain south of Haifa, a region northeast of the Gaza District, and the southern part of the Beersheba sub-District, sale of land by a Palestinian Arab was forbidden except to a Palestinian Arab with similar exceptions. In the "free zone," which consisted of Haifa Bay, the coastal plain from Zikhron Ya'akov to Yibna, and the neighborhood of Jerusalem, there were no restrictions. The reason given for the regulations was that the Mandatory was required to "ensur[e] that the rights and positions of other sections of the population are not prejudiced," and an assertion that "such transfers of land must be restricted if Arab cultivators are to maintain their existing standard of life and a considerable landless Arab population is not soon to be created"[18]

By the 1947–1949 Palestine war, the Survey of Palestine had finalized topographical maps for all of the country except the southern Negev,[19] although it had confirmed land title in less than 20% of the country, specifically in the areas of Jewish settlement.[20] A cadastral survey was not carried out in the areas which would become the West Bank until after 1948; a situation which caused significant challenges in subsequent years.[21][22]

The department grew significantly throughout the mandate period: it began with 46 professionals in 1921, of which 25 were recruited from outside Palestine, and by 1942 had 215 professionals, with only 11 recruited from outside Palestine. The Survey of Palestine printed 1,800 maps and plans in 1926, 19,000 in 1929, 64,000 in 1933 and 100,000 in 1939.[23] There were two schools for training Palestinian and Arab surveyors, one in Jenin that operated for one year starting 1942, and the other in Nazareth that opened in 1944.[24]

In early 1948, temporary Directors General of the Survey Department were appointed for each of the expected "Jewish State" and "Arab State" under the terms of the United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine, and the pre-existing files and maps were to be shared.[25] However, during the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, British lorries delivering the "Arab state" portion of their maps were diverted back to Tel Aviv.[20] Today, the historical maps are held at the Survey of Israel, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development and Israeli Ministry of Defense archives.[20]

Land disputes

In 1937, then Commissioner of Lands and Surveys, Lieutenant Colonel F. J. Salmon, described the importance of the department's work with respect to allowing land purchases:[26]

In the Ottoman days, a title to a piece of land in Palestine was a very vague document. There was no survey, recording shape, area or position; the description was usually, to say the least of it, ambiguous, and the extent which was the gauge for taxation, was almost invariably falsified to save the pocket of the owner. Big blocks were, and in areas where there has been no land settlement, still are, shared by large numbers of owners who have no defined boundaries and who often alter the position of their plots from year to year… To purchase land from a title owner, or worse still, from an occupier who had no title, was a very uncertain business, and often still is. The difficulty, however, is now being solved, though very slowly, by Land Settlement… The claims are recorded and examined by Palestinian Assistant Settlement Officers, while cases of dispute are heard by British Land Settlement Officers… Even in areas that are not under Settlement, a land-owner can apply for an authoritative registration of title on a modern survey, but if there is a dispute, this has to be settled by the Land Court, a much slower, more expensive and laborious proceeding than an investigation and judgment by a Settlement Officer.

Notable publications

- "Palestine Index to Villages & Settlements" (see here), an administrative map without relief, usually on a single-sheet 1:250,000 scale, was often used as a base for overprinted thematic maps.[27]

- 1:500,000 motor map (see here): the 1:500,000 motor map followed the 1:100,000 map.[14]

Notable survey laws (ordinances)

The Mandate government laws regulated and empowered surveying, surveyors, and survey fees.

- Cadastral Survey Ordinance 1920, published in the Official Gazette in July 1920. Initially limited to the districts of Gaza and Beersheba, extended to the whole country in February 1921 Land Surveyors Ordinance 1925[28]

- Land Surveyors Ordinance 1925, published on 1 May 1925, required registration of landed property to be based on an approved plan, and standardized the requirements for all such survey maps[28]

- Land Settlement Ordinance 1928, established the use of the Torrens system of cadastral (ownership) registration[28]

- Survey Ordinance, Surveyors Regulations 1930, required certain metric scales such as an "even multiple of 1:10,000" and for individual properties "a scale of 1:2,500, 1:625, or larger".[28]

- Survey Ordinance, Surveyors Regulations 1938, update of prior regulations, not annulled and replaced until Israel's Surveyors Regulations 1965 on 5 August 1965.[28]

Directors

- June – Dec.1920: Major Cecil Verdon Quinlan[29]

- 1920–1931/2: Major Cuthbert Hilliard Ley[29]

- 1931–1933: Robert Barker Crusher (acting)[29]

- 1933–1938: Lieutenant Colonel Frederick John Salmon "Commissioner of Lands and Surveys"[29]

- 1938–1939: James Nelson Stubbs (acting)[29]

- 1940–1948: Andrew Park Mitchell[29]

Headquarters

The first headquarters – in early 1920 – were based in Gaza City; they moved to Jaffa just a few months later.[30] On 1 January 1931 a purpose-built building was opened to house the department at the southern end of a 30-acre (12 ha) plot near the German Templar colony on the outskirts of Tel Aviv (the location can be seen on this 1930 map).[31] The location of the headquarters in the coastal plain favored for Zionist settlement, together with the fact that all other offices of the Mandate Government were in Jerusalem, have been said to emphasize "the strong link between the cadastral survey of Palestine and Zionist motives".[32] Proposals to move the office to Jerusalem were raised in 1925, 1928 and 1935, but to no avail.[33][34]

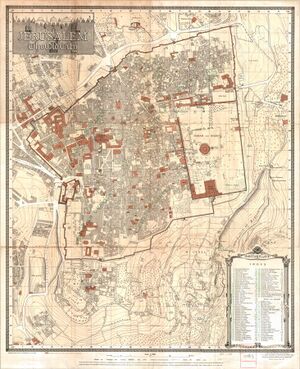

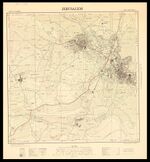

1945 maps of Jerusalem and environs

| 1:10,000 | 1:5,000 | 1:2,500 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | A | B | ||||||

|

|

1 |

|

|

1 |

| |||

|

|

2 |

|

|

2 | ||||

|

|

3 | |||||||

| Each sheet is a separate clickable image. | |||||||||

1:20,000 maps – Earliest available

See also

References

- ↑ Mitchell 1942, p. 389: "The Survey of Palestine was established in 1920 at Jaffa"

- ↑ Gavish 2005, pp. 73–75.

- ↑ "Important dates in the history of the Survey of Israel (Previously: Survey Department and Survey Section 1948-1971)". 2022-08-20. https://www.mapi.gov.il/en/Heritage/Pages/Important-dates-in-the-history-of-the-Survey-of-Israel.aspx.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Weaver, Alain Epp (2014). ""Homecoming Is Out of the Question" Palestinian Refugee Cartography and Edward Said's View from Exile". Mapping Exile and Return: Palestinian Dispossession and a Political Theology for a Shared Future. Fortress Press. pp. 25–58. ISBN 978-1-4514-7012-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=NiedAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA50.

- ↑ Rempel, Terry (2012). "Review of Atlas of Palestine, 1917–1966". Holy Land Studies 11: 225–227. doi:10.3366/hls.2012.0048.

- ↑ "Palestinian oral history map launched". Middle East Monitor. 13 June 2019. https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20190613-palestinian-oral-history-map-launched/.

- ↑ Mitchell 1942, pp. 388–389.

- ↑ Arden-Close 1942, p. 501.

- ↑ "War Office: Geographical Section General Staff and Historical Section: War of 1914–1918: Palestine Campaign: Maps" (in English). The National Archives (United Kingdom). 1880–1984. https://discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk/details/r/C14507.

- ↑ (in en) TM5-248, Foreign Maps. Technical Manuals. United States Department of the Army. 1956. pp. 116ff. https://books.google.com/books?id=ybAXAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA116.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Abu Sitta 2006, pp. 101–102: "Contrary to general practice in which country surveys started with topographical maps to describe the earth surface, there was a great rush to produce cadastral maps. The aim was to undertake “legal examination of the validity of all land title deeds in Palestine," in Weizmann's words. Thus, the extent and identity of private land ownership would be determined. All else would be "state or waste land," open for Jewish settlement… This meant that the mandate government effectively held all land in Palestine under its control and released only those lots for which the owner provided absolute proof of ownership. Since much land was held by Custom Law – by long-term recognition of ownership – or held in common ownership or used for grazing or woods, this system, and particularly the Zionist motives behind it, was resisted by the Palestinians, to the extent of chasing the surveyors away or destroying their equipment."

- ↑ Essaid 2013, pp. 97–102.

- ↑ Essaid 2013, p. 101c: “The British Government was under pressure to complete the authentication of land title in Palestine, because once titles had been validated, classification of the land would also be validated, distinguishing privately-owned land from state and waste lands, and thereby identifying lands “open for Jewish settlement."… To "implement its commitments," the government had to organize a legal land tenure system for land settlement, and as Gavish concludes, "Such a land settlement was impossible to achieve without surveying and mapping." The Zionist Organization used surveying and mapping to differentiate the types of lands (such as distinguishing "state domain and uncultivated lands") as a means towards the fulfillment of the Balfour Declaration."

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Mitchell 1942, pp. 389–391.

- ↑ Colonel Ley, 'An Outline of Cadastral Structure in Palestine', in "Report of the 1931 Conference of Empire Surveyors" (H.M.S.O., 1932)

- ↑ H. B. T. 1948, p. 325a: "The whole country except for the Beersheba sub-district had, by 1934, been surveyed without contours on 1/10,000 scale for fiscal purposes. These surveys formed the basis for a 1/20,000 (and 1/100,000) topographical series for which contours were compiled from new work. Prior to 1940 the published 1/20,000 sheets, numbering some 45, covered only the coastal plain… virtually the whole settled area north of the latitude of Beersheba had, by 1948, been covered with about 150 sheets."

- ↑ H. B. T. 1948, p. 324: "As from 1 April, 1940, the Department shed its responsibilities for land settlement – that is the actual adjudication work – and for land registration; and was thus free to concentrate upon the surveys and demarcations called for by the Land (Settlement of Title) Ordinance, 1928."

- ↑ A Survey of Palestine (Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry), vol. 1, chapter VIII, section 7, Government Printer of Jerusalem, pp. 260–262

- ↑ H. B. T. 1948, p. 325b: "By 1940 the cultivable area of Palestine was already provided with an adequate net-work of major triangulation, and in 1941 this was expanded into neighbouring territories, when Army surveyors observed a chain connecting Palestine major points south of Beersheba with Egyptian geodetic points in Sinai, thence south to the Gulf of Aqaba and north through Transjordan to close on the Palestine major net near Jericho. The area thus covered is for the most part desert. This apart, the only triangulation executed during these years was fourth-order work needed for cadastral surveys; and of this the only area still outstanding is to the south and east largely desert and without settled population."

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Abu Sitta 2006, pp. 101–102.

- ↑ Essaid 2013, p. 99: "…during the Mandate the land and villages of Palestine that currently make up the territory of the West Bank did not undergo a cadastral survey until after 1948. When the West Bank became part of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the Department of Lands and Survey employed Palestinian surveyors from the area to map the land and villages. Therefore the land of what is now the Palestinian territory of the West Bank had been surveyed by the Ottomans and others before the British Mandate of Palestine, and the cadastral survey was carried out while it was under Jordanian rule, but was not surveyed in between by the British. It was also confirmed that the land in the West Bank today was also not surveyed until the territory came under Jordanian rule. Palestinian surveyors based in Jerusalem who worked for the Jordanian Department of Lands and Survey were interviewed about this, and confirmed that since there were no British maps or notes to work from, they had to start from scratch in the cadastral survey, parcellation, and registration of title of the lands. Furthermore, at the Jordanian Department of Lands and Survey in Amman, it was observed that when an enquiry regarding the location of a piece of land could not be resolved on the basis of the Jordanian surveys, the sources utilized were the Ottoman tabus. Therefore, with the absence of cadastral maps during the British Mandate for the land of the West Bank, parcellation and registration could not exist, and official transfers of land could not take place."

- ↑ Gavish & Kark 1993, pp. 70–80: "by 1948, the Mandatory Government of Palestine had completed the land settlement of only about five million metric dunams, which represent just 20 per cent of the 26 300 square kilometers of the total land area of Palestine… This settled area is almost identical to the boundaries of the northern part of the State of Israel recognized by the United Nations in 1947. Judea and Samaria, which were occupied by the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan from 1948 until 1967, were not surveyed under the cadastral project and, therefore, have remained ever since the focus of constant disputes over landownership."

- ↑ Mitchell 1942, p. 392.

- ↑ Gavish, Dov (2010). The survey of Palestine under the British Mandate, 1920–1948. London: Routledge. pp. 173. ISBN 978-0-415-59498-1. OCLC 632081415. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/632081415.

- ↑ Important dates in the history of the Survey of Israel (Previously: Survey Department and Survey Section 1948–1971)

- ↑ Salmon 1937, p. 33.

- ↑ Levin, Noam; Kark, Ruth; Galilee, Emir (January 2010). "Maps and the settlement of southern Palestine, 1799–1948: an historical/GIS analysis". Journal of Historical Geography 36 (1): 9. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2009.04.001.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 Gavish 2005, pp. 240–244.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 Gavish 2005, p. 48.

- ↑ Essaid 2013, p. 101.

- ↑ Mitchell 1942, p. 390.

- ↑ Essaid 2013, p. 100-101: "...as Abraham Granovsky explained in Land Policy in Palestine, Zionists were only interested in using their national capital to purchase land in the coastal plain and the north of Palestine... There were other points that emphasized the strong link between the cadastral survey of Palestine and Zionist motives. One of the major ones, as discussed by Gavish, was the location of the office of the Survey Department. All offices of the Mandate Government in Palestine were based in Jerusalem, except that of the Survey Department. Gavish explained that the reason behind the different location was 'the directive to survey the coastal plain first.'"

- ↑ Essaid 2013, p. 101b: "By 1929, it was concluded that it would be more economical to construct a building, and that “the department should remain in Jaffa as long as the land settlement process was going on in the vicinity, and there was no choice but to set up a special building for the Survey." The issue, however, is that since the Survey Department's Office was in Jaffa, the lands that were surveyed and settled were those lands nearest to Jaffa, along the coast to the north and south of Jaffa, along with the northern part of Palestine."

- ↑ Gavish 2005, p. 56: “Thus, the site of the Survey of Palestine was determined by its close proximity to the heart of the region of the cadastral survey, even at the cost of efficient communications with other governmental departments and offices."

Bibliography

- Abu Sitta, Salman (2006). "Map and Grab". Journal of Palestine Studies XXXV (2): 101–102. ISSN 0377-919X. https://www.academia.edu/14941926.

- Essaid, Aida (4 December 2013). "Land Settlement, Surveys and Disputes". Zionism and Land Tenure in Mandate Palestine. Routledge. pp. 97–102. ISBN 978-1-134-65361-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=yNpJAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA98.

- Gavish, Dov (2005). "The first maps based on origin surveys". A Survey of Palestine Under the British Mandate, 1920–1948. RoutledgeCurzon Studies in Middle East History. London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon. ISBN 978-0-7146-5651-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=KBSDam2TDaEC.

- Gavish, Dov; Kark, Ruth (1993). "The Cadastral Mapping of Palestine, 1958–1928". The Geographical Journal 159 (1): 70–80. doi:10.2307/3451491. Bibcode: 1993GeogJ.159...70G.

- Mitchell, Andrew Park (1942). "Survey of Palestine: The First Twenty Years". Empire Survey Review 6 (45): 388–392. doi:10.1179/sre.1942.6.45.388.

Further reading

- Horovitz, Yechiel (Hilik). "The Survey of Israel Heritage Website (Fig Working Week Pre-Conference Workshop Eilat, 3 May 2009)". https://www.fig.net/resources/proceedings/fig_proceedings/fig2009/ppt/hs01/hs01_horovitz_ppt_3296.pdf.

- Khalidi, Walid (1992). All That Remains: The Palestinian Villages Occupied and Depopulated by Israel in 1948. Inst for Palestine Studies. ISBN 978-0-88728-224-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=_By7AAAAIAAJ.

- Loxton, J.W. (1947). "Systematic Surveys for Settlement of Title and Registration of Rights to Land in Palestine". Report of the Conference of Colonial Government Statisticians. H.M. Stationery Office. https://books.google.com/books?id=mQsiAQAAIAAJ.

- Sitta, Salman Abu (2016). Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-977-416-730-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=xpzSDAAAQBAJ.

- Sitta, Salman Abu (2010). Atlas of Palestine, 1917–1966. Palestine Land Society. pp. 689. ISBN 978-0-9549034-2-8.

- Srebro, Haim (2009). 60 Years of Surveying and Mapping Israel, 1948-2008. Survey of Israel. ISBN 978-965-91256-1-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=-WCnbnn_4JgC.

- "Detailed Map Series from the British Mandate Period". https://web.nli.org.il/sites/nli/english/digitallibrary/laor-collection/news/pages/-pal-1157.aspx.

- "Mandate for Palestine – Report of the Mandatory to the League of Nations (Report by His Majesty's Government in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland to the Council of the League of Nations on the Administration of Palestine and Trans-Jordan for the year 1930)". United Nations. https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-193812/.

|