Philosophy:I know that I know nothing

|

| Part of a series on |

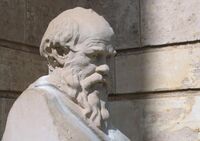

| Socrates |

|---|

|

"I know that I know nothing" "The unexamined life is not worth living" gadfly · Trial of Socrates |

| Eponymous concepts |

|

Socratic dialogue · Socratic intellectualism Socratic irony · Socratic method Socratic paradox · [[Socratic questioning]] Socratic problem · Socratici viri |

| Disciples |

|

Plato · Xenophon Antisthenes · [[Biography:AristipAristippus · Aeschines of Sphettus|Aeschines]] |

| Related topics |

| Academic Skepticism · Megarians · Cynicism · Cyrenaics · Platonism · Aristotelianism · Stoicism · Virtue ethics · The Clouds |

|

|

"I know that I know nothing" is a saying derived from Plato's account of the Greek philosopher Socrates: "For I was conscious that I knew practically nothing..." (Plato, Apology 22d, translated by Harold North Fowler, 1966).[1] It is also sometimes called the Socratic paradox, although this name is often instead used to refer to other seemingly paradoxical claims made by Socrates in Plato's dialogues (most notably, Socratic intellectualism and the Socratic fallacy).[2]

This saying is also connected or conflated with the answer to a question Socrates (according to Xenophon) or Chaerephon (according to Plato) is said to have posed to the Pythia, the Oracle of Delphi, in which the oracle stated something to the effect of "Socrates is the wisest person in Athens."[3] Socrates, believing the oracle but also completely convinced that he knew nothing, was said to have concluded that nobody knew anything, and that he was only wiser than others because he was the only person who recognized his own ignorance.

Etymology

The phrase, originally from Latin ("ipse se nihil scire id unum sciat"),[4] is a possible paraphrase from a Greek text (see below). It is also quoted as "scio me nihil scire" or "scio me nescire".[5] It was later back-translated to Katharevousa Greek as "[ἓν οἶδα ὅτι] οὐδὲν οἶδα", [hèn oîda hóti] oudèn oîda).[6]

In Plato

This is technically a shorter paraphrasing of Socrates' statement, "I neither know nor think I know" (in Plato, Apology 21d). The paraphrased saying, though widely attributed to Plato's Socrates in both ancient and modern times, actually occurs nowhere in Plato's works in precisely the form "I know I know nothing."[7] Two prominent Plato scholars have recently argued that the claim should not be attributed to Plato's Socrates.[8]

Evidence that Socrates does not actually claim to know nothing can be found at Apology 29b-c, where he claims twice to know something. See also Apology 29d, where Socrates indicates that he is so confident in his claim to knowledge at 29b-c that he is willing to die for it.[citation needed]

That said, in the Apology, Plato relates that Socrates accounts for his seeming wiser than any other person because he does not imagine that he knows what he does not know.[9]

... ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

... I seem, then, in just this little thing to be wiser than this man at any rate, that what I do not know I do not think I know either. [from the Henry Cary literal translation of 1897]

A more commonly used translation puts it, "although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is – for he knows nothing, and thinks he knows. I neither know nor think I know" [from the Benjamin Jowett translation]. Regardless, the context in which this passage occurs is the same, independently of any specific translation. That is, Socrates having gone to a "wise" man, and having discussed with him, withdraws and thinks the above to himself. Socrates, since he denied any kind of knowledge, then tried to find someone wiser than himself among politicians, poets, and craftsmen. It appeared that politicians claimed wisdom without knowledge; poets could touch people with their words, but did not know their meaning; and craftsmen could claim knowledge only in specific and narrow fields. The interpretation of the Oracle's answer might be Socrates' awareness of his own ignorance.[10]

Socrates also deals with this phrase in Plato's dialogue Meno when he says:[11]

καὶ νῦν περὶ ἀρετῆς ὃ ἔστιν ἐγὼ μὲν οὐκ οἶδα, σὺ μέντοι ἴσως πρότερον μὲν ᾔδησθα πρὶν ἐμοῦ ἅψασθαι, νῦν μέντοι ὅμοιος εἶ οὐκ εἰδότι.

[So now I do not know what virtue is; perhaps you knew before you contacted me, but now you are certainly like one who does not know.] (trans. G. M. A. Grube)

Here, Socrates aims at the change of Meno's opinion, who was a firm believer in his own opinion and whose claim to knowledge Socrates had disproved.

It is essentially the question that begins "post-Socratic" Western philosophy. Socrates begins all wisdom with wondering, thus one must begin with admitting one's ignorance. After all, Socrates' dialectic method of teaching was based on that he as a teacher knew nothing, so he would derive knowledge from his students by dialogue.

There is also a passage by Diogenes Laërtius in his work Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers written hundreds of years after Plato, where he lists, among the things that Socrates used to say:[12] "εἰδέναι μὲν μηδὲν πλὴν αὐτὸ τοῦτο εἰδέναι", or "that he knew nothing except that he knew that very fact (i.e. that he knew nothing)".

Again, closer to the quote, there is a passage in Plato's Apology, where Socrates says that after discussing with someone he started thinking that:[9]

τούτου μὲν τοῦ ἀνθρώπου ἐγὼ σοφώτερός εἰμι· κινδυνεύει μὲν γὰρ ἡμῶν οὐδέτερος οὐδὲν καλὸν κἀγαθὸν εἰδέναι, ἀλλ᾽ οὗτος μὲν οἴεταί τι εἰδέναι οὐκ εἰδώς, ἐγὼ δέ, ὥσπερ οὖν οὐκ οἶδα, οὐδὲ οἴομαι· ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

I am wiser than this man, for neither of us appears to know anything great and good; but he fancies he knows something, although he knows nothing; whereas I, as I do not know anything, do not fancy I do. In this trifling particular, then, I appear to be wiser than he, because I do not fancy I know what I do not know.

It is also a curiosity that there is more than one passage in the narratives in which Socrates claims to have knowledge on some topic, for instance on love:[13]

How could I vote 'No,' when the only thing I say I understand is the art of love? (τὰ ἐρωτικά)[14]

I know virtually nothing, except a certain small subject – love (τῶν ἐρωτικῶν), although on this subject, I'm thought to be amazing (δεινός), better than anyone else, past or present.[15]

Alternative usage

"Socratic paradox" may also refer to statements of Socrates that seem contrary to common sense, such as that "no one desires evil".[16]

See also

- Acatalepsy

- Academic skepticism

- Metamemory

- Apodicticity

- Cogito

- Dunning–Kruger effect

- Doxastic logic, Doxastic attitudes

- Epistemology

- Gnothi seauton

- Ignoramus et ignorabimus

- Maieutics

- Münchhausen trilemma

- Pyrrhonism

- Sapere aude

- Skepticism

- There are known knowns

- Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

References

- ↑ Plato. Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 1 translated by Harold North Fowler; Introduction by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1966.

- ↑ "Socratic Paradox". https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803100515858.

- ↑ H. Bowden, Classical Athens and the Delphic Oracle: Divination and Democracy, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p. 82.

- ↑ "He himself thinks he knows one thing, that he knows nothing"; Cicero, Academica, Book I, section 16.

- ↑ A variant is found in von Kues, De visione Dei, XIII, 146 (Werke, Walter de Gruyter, 1967, p. 312): "...et hoc scio solum, quia scio me nescire [sic]... [I know alone, that (or because) I know, that I do not know]."

- ↑ "All I know is that I know nothing -> Ἓν οἶδα ὅτι οὐδὲν οἶδα, Εν οίδα ότι ουδέν οίδα, ΕΝ ΟΙΔΑ ΟΤΙ ΟΥΔΕΝ ΟΙΔΑ". https://www.translatum.gr/forum/index.php?topic=918.0.

- ↑ Gail Fine, "Does Socrates Claim to Know that He Knows Nothing?", Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy vol. 35 (2008), pp. 49–88.

- ↑ Fine argues that "it is better not to attribute it to him" ("Does Socrates Claim to Know He Knows Nothing?", Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy vol. 35 (2008), p. 51). C. C. W. Taylor has argued that the "paradoxical formulation is a clear misreading of Plato" (Socrates, Oxford University Press 1998, p. 46).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Plato, Apology 21d.

- ↑ Plato; Morris Kaplan (2009). The Socratic Dialogues. Kaplan Publishing. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-4277-9953-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=SSous9E-3CwC&pg=PR9.

- ↑ Plato, Meno 80d1–3.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius II.32.

- ↑ Cimakasky, Joseph J. All of a Sudden: The Role of Ἐξαίφνης in Plato's Dialogues. Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation. Duquesne University. 2014.

- ↑ Plato. Symposium, 177d-e.

- ↑ Plato. Theages, 128b.

- ↑ Terence Irwin, The Development of Ethics, vol. 1, Oxford University Press 2007, p. 14; Gerasimos Santas, "The Socratic Paradoxes", Philosophical Review 73 (1964), pp. 147–64.

External links

|