Biography:Benjamin B. Talley

Benjamin Branche Talley (July 29, 1903 – November 27, 1998) was an American engineer. He was involved in military construction in Alaska before and after World War II, and earned the nickname "the Father of Military Construction in Alaska".[1] He was involved in planning the Normandy landings and Battle of Okinawa during World War II. After the war, Talley led various engineering districts, including the North Atlantic Division, before retiring as a brigadier general in 1956. After retirement, he was involved in civil engineering and oversaw the reconstruction of central Alaska after the Good Friday earthquake.

Early and personal life

Talley was born in Greer County, Oklahoma on July 29, 1903. He graduated from high school in Enid, Oklahoma, and attended Oklahoma A&M College. Talley graduated from Georgia Tech in 1925 with an electrical engineering degree, and from the Graduate Engineering School of Westinghouse Electric Corporation in 1926.[2][3][4] He was married three times and survived by a son.[2][5]

Army service

Talley first entered the military as a reserve officer in the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps in the mid-1920s.[6] He joined the United States Army in June 1926.[4] As a second lieutenant,[6] Talley was stationed with the 2nd Engineer Battalion in Texas and Colorado before attending the Engineer School in Virginia.[2] He was then involved in the Nicaragua Canal Survey and assisted in the aftermath of the 1931 Nicaragua earthquake.[7] Talley was assigned to put out the ensuing fire after the earthquake hit Managua.[8] When Talley returned to the United States, he worked to make maps based on aerial photographs for nine years, publishing the textbook Photogrammetry. He also invented a 'portable stereocomparagraph' and lectured at Harvard University.[2][3] He was executive officer to the district engineer based in Portland, Oregon .[6]

In Alaska

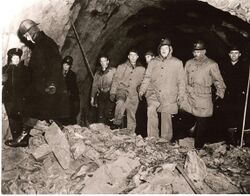

In the lead-up to the American entry into World War II, on September 11, 1940, Talley, by then a captain, traveled to Yakutat, Alaska, where he had been placed in charge of the construction of Elmendorf Air Force Base .[3][7][9] On January 15, 1941[6] he became area engineer for Army construction in Alaska, supervising the construction of twenty-eight projects totaling around 300 million dollars. He had traveled to Anchorage, through Seward, on January 7.[10] Convinced that the United States was going to enter the World War soon, he ordered construction to continue on projects such as Elmendorf throughout the winter. Talley was in the field for two-thirds of his time,[11] flying over 900 hours in two and a half years. On May 1, 1941 his role was renamed 'officer in charge, Alaska construction', and he became a member of the Alaska Defense Command's staff. He worked to improve the state's shipping capabilities and rehabilitate Anchorage's harbor.[12]

By October 1942 Talley was a colonel.[9] In November he visited John L. DeWitt, commander of the Western Defense Command, in San Francisco to get several projects approved. He arrived back in Alaska on December 6, just a day before the Attack on Pearl Harbor.[13] He oversaw construction of a secret base on Umnak that protected Dutch Harbor from a Japanese attack.[3] Talley examined numerous of the Aleutian Islands as potential locations for airfields, visiting several of them. He was given broad authority over construction and was made the head of the Army Transport Service's Alaska division, though he eventually lost that role after diverting a ship to supply Umnak. Because he employed the most people in the state, Talley represented the United States Department of Labor.[14] His obituary wrote that he "supervised virtually all Army and Army Air Corps projects in Alaska as the military prepared for the Japanese invasion of Alaska."[7] On January 11, 1943 he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for "exceptionally meritorious and distinguished service as officer in charge of Alaska construction".[15]

In Europe and to the end of World War II

In June 1943 Talley traveled to Europe, where he helped plan the Normandy landings and served as the V Corps' deputy chief of staff.[2][3][16] General Leonard T. Gerow, the Corps' commander, was impressed by Talley and assigned him to observe the landing on Omaha Beach and report back to Gerow on the progress of the invasion. The majority of the 1st Infantry Division's officers disliked Talley by the time the operation was launched, considering him "a thorn in our side" because he treated them as though they knew little about planning an amphibious invasion.[1] He was given command of the beach, overseeing supplies as they flowed into the region. As commander of the area, he oversaw up to 63,000 soldiers— responsibility that the Anchorage Daily News considered was typically held by a three star general. For this he earned the Legion of Merit and the Distinguished Service Cross. In December 1944 he assumed command of the 1st Engineer Special Brigade.[2][3][16]

Under Talley's command, the brigade headquarters returned to England, and embarked for the United States on 23 December 1944. It arrived at Fort Dix, New Jersey, on 30 December. After four weeks leave, it reassembled at Fort Lewis, Washington. Part of the brigade headquarters went by air to Leyte to join the XXIV Corps for the invasion of Okinawa—which Talley helped plan, while the rest traveled directly to Okinawa on the USS Achernar.[7][17] Talley was awarded the Croix de guerre with palm in 1945.[3] The brigade was in charge of unloading on Okinawa from 9 April to 31 May. It then prepared for the invasion of Japan. This did not occur due to the end of the war, and the brigade landed in Korea on 12 September 1945.[18] Talley was deputy commander of the Army Special Forces in Korea after victory over Japan.[2]

Later career

Talley was subsequently district engineer for Huntington, West Virginia and later Louisville, Kentucky.[2] He entered the National War College in 1949[19] and was head of the estimates branch of the intelligence division on the Army General Staff from 1949 to 1952,[5] briefing the Joint Chiefs of Staff on the Soviet Union's military capacity during the Korean War and other relevant intelligence.[2] In March 1952 it was reported that Talley had been promoted to division engineer of the North Atlantic Division by Lieutenant General Lewis A. Pick. As division engineer, he oversaw construction projects totaling around $900 million.[16] On April 7, 1955 he was promoted to brigadier general.[20] Talley became division engineer of the Mediterranean Division, Nouasseur Air Base in 1955.[16] He administered the Mediterranean division for ten months, from June 28, 1955, to May 1, 1956, refocusing the division on the Middle East from North Africa.[21] He retired as a brigadier general on April 30, 1956.[16]

Retirement and death

After retirement, Talley lived in New York City , Oklahoma, and Alaska.[2][5] He worked for Raymond International and supervised the construction of 11 buildings in Brasília as the Brazilian capital was under construction. He was resident manager of the Metcalf and Eddy group, and oversaw the group as it rebuilt Anchorage, Alaska, after the 1964 Alaska earthquake and worked in Da Nang during the Vietnam War.[7][22][23] In the 1980s, he was on a committee advising on the documentary Alaska at War, which premiered in 1986. Talley died on November 27, 1998 in Homer, Alaska, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[2] As of 2021, there is a scholarship at the University of Alaska named after Talley and his wife, Virginia.[24]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 McManus 2019, pp. 195–196.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 "Obituaries". Anchorage Daily News: p. B3. 1 December 1998.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 "Atlantan Stars As Mapper". The Atlanta Constitution: pp. 10. 1945-10-02. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53570790/atlantan-stars-as-mapper/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Oklahoman Heads NATO's Engineers". Arizona Daily Star: pp. 15. 1952-03-23. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53571255/oklahoman-heads-natos-engineers/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Benjamin B. Talley papers" (in en-US). https://archives.consortiumlibrary.org/collections/specialcollections/hmc-0241/.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Mighetto & Homstad 1997, p. 28.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 "Obituary for Benjamin B. Talley (Aged 95)". The Indianapolis News: pp. 35. 1998-11-28. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53570552/obituary-for-benjamin-b-talley-aged/.

- ↑ Ingersoll, Ernest (1931) (in en). Explorers Journal. Explorers Club. pp. 43. https://books.google.com/books?id=GmosAAAAMAAJ&q=%22BENJAMIN+BRANCHE+TALLEY-Active+Non-Resident.+When+fire+followed+the+earthquake+at+Managua,+Nicaragua,+in+March+of+this+year,+the+job+of+extinguishing+it+was+given+to+Lieutenant+Talley,+who+happened+to+be+attached+to+the+Nicaragua%22.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Chandonnet 2007, p. 59.

- ↑ Chandonnet 2007, pp. 60–61; 65.

- ↑ Chandonnet 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ Mighetto & Homstad 1997, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Chandonnet 2007, pp. 20; 61.

- ↑ Chandonnet 2007, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ "Government Honors Alean Army Officer". The Salt Lake Tribune: pp. 4. 1943-01-12. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53570675/government-honors-alean-army-officer/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 "Col. Talley Named Division Engineer". The News: pp. 19. 1952-03-26. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53570933/col-talley-named-division-engineer/.

- ↑ Heavey 1988, p. 177.

- ↑ Cullum 1950, p. 941.

- ↑ (in en) Explorers Journal. Explorers Club. 1949. pp. 18. https://books.google.com/books?id=TU1gAAAAIAAJ.

- ↑ "B. B. Talley Gets Army Star". The New York Times. April 8, 1955.

- ↑ Grathwol & Moorhus 2009, p. 94.

- ↑ "Hub Firm Finds Construction Unpredictable at the Front". The Boston Globe: pp. 14. 1967-02-03. https://www.newspapers.com/clip/53571426/hub-firm-finds-construction/.

- ↑ "Alaskan Gen. Benjamin B. Talley." ENR, vol. 242, no. 2, 1999, pp. 21.

- ↑ "Benjamin B. and Virginia M. Talley Scholarship". https://alaska.academicworks.com/donors/benjamin-b-and-virginia-m-talley-scholarship.

Bibliography

- Cullum, George W. (1950). Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the US Military Academy at West Point New York Since Its Establishment in 1802: Supplement Volume IX 1940–1950. Chicago, Illinois: R. R. Donnelly and Sons, The Lakeside Press. http://digital-library.usma.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p16919coll3/id/22314/rec/10. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- Heavey, William F. (1988). Down Ramp! The Story of the Army Amphibian Engineers. Nashville, Tennessee: The Battery Press. ISBN 0-89839-123-7. OCLC 270398219.

- Chandonnet, Fern (2007) (in en). Alaska at War, 1941-1945: The Forgotten War Remembered. College, Alaska: University of Alaska Press. ISBN 978-1-60223-135-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=p01bFVagOJYC.

- Grathwol, Robert P.; Moorhus, Donita M. (2009) (in en). Bricks, Sand, and Marble: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Construction in the Mediterranean and Middle East, 1947-1991. Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, Corps of Engineers, U.S. Army. https://books.google.com/books?id=HCAQHPJRiokC.

- Mighetto, Lisa; Homstad, Carla (1997) (in English). Engineering in the Far North: A History of the U.S. Army Engineer District in Alaska, 1867-1992. Washington, D.C.: Historical Research Associates, Inc.; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. OCLC 992714929. http://cdm16021.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/p16021coll4/id/101.

- McManus, John C. (2019) (in en). The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: the Big Red One at Omaha Beach. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-1-5247-4550-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=sWCUDwAAQBAJ&q=%22the+Father+of+Military+Construction+in+Alaska%22&pg=PA195.

Further reading

- Cloe, John Haile (2017). Attu : the forgotten battle. Anchorage, Alaska: National Park Service. ISBN 978-0-9965837-3-2. OCLC 1014124889. http://npshistory.com/publications/aleu/attu-forgotten-battle.pdf.

- World War 11 In Alaska: A Historic and Resources Plan

External links