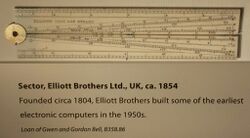

Company:Elliott Brothers (computer company)

Elliott Brothers (London) Ltd was an early computer company of the 1950s and 1960s in the United Kingdom. It traced its descent from a firm of instrument makers founded by William Elliott in London around 1804. The research laboratories were originally set up in 1946 at Borehamwood and the first Elliott 152 computer appeared in 1950.

In its day the company was very influential. The computer scientist Bobby Hersom was an employee from 1953 to 1954, and Sir Tony Hoare was an employee there from August 1960 to 1968. He wrote an ALGOL 60 compiler for the Elliott 803. He also worked on an operating system for the new Elliott 503 Mark II computer.[1] The founder of the UK's first software house, Dina St Johnston, had her first programming job there from 1953 to 1958, and John Lansdown pioneered the use of computers as an aid to planning on an Elliott 803 computer in 1963. In 1966 the company established an integrated circuit design and manufacturing facility in Glenrothes, Scotland, followed by a metal–oxide semiconductor (MOS) research laboratory.

In 1967, Elliott Automation was merged into the English Electric company and in 1968 the computer part of the company became part of International Computers Limited (ICL).

Origins

William Elliott was born in either 1780 or 1781 and apprenticed to the instrument maker William Blackwell in 1795. In 1804, Elliott began his own company to make drawing instruments, scales, and scientific instruments. In 1850, his two sons Charles and Fredrick joined his business. The company prospered, and manufactured a range of surveying, navigational, and other instruments. William Elliott died in 1853. In the 1850s the company began manufacturing electrical instruments, which were used by researchers such as James Clerk Maxwell and others. Charles Elliott retired in 1865, and when Frederick died in 1873 he left the business to his wife Susan.

In 1876, the company expanded to a new factory to manufacture telegraph equipment and instruments for the British Admiralty. There was increased demand for electrical switchboards for the growing electric power industry. Susan Elliott became partners with Willoughby Smith, who had significant expertise in telegraphic instruments; she was the last Elliott family member associated with the company when she died in 1880. Smith in turn brought his sons in to manage the company operations.

In 1893, the instrument making company Theilers joined Elliotts, with W. O. Smith and G. K. E. Elphinstone as managers. Elphinstone had useful connections with the British Navy. He was knighted for his contributions at Elliotts during World War I, with developments in gunnery instruments for the Navy.[2]

In 1898, the company moved out of London to a new site in Kent. One of the main products at this site was naval gunnery tables, which were mechanical analog computers, which were manufactured until after World War II. Aircraft instruments became an important product line with the development of heavier than air flight; instruments such as tachometers and altimeters were vital in aviation. In 1916, the company changed its name to Elliott Brothers (London), Limited.[3] In 1920, Siemens Brothers started purchasing shares of the company.

The end of Admiralty contracts after the war severely affected Elliott Brothers, which had not been involved in radar and electronics technology during the war. Siemens Brothers had sold their interest in the company, and a new director, Leon Bagrit, was instrumental in rebuilding and redirecting the firm into new areas.

In 1946, John Flavell Coales founded the Research Laboratories of Elliott Brothers at Borehamwood. This laboratory was the site of development of radar systems for the Government, and in 1947 produced a stored-program digital computer. By 1950 the laboratory had a staff of 450, and had developed the commercial Elliott 401 computer. In 1953, Elliott formed an "Aviation Division" at Borehamwood.[3] In 1957, the company changed its name to Elliott Automation Ltd.

By 1966, Elliott Automation had started their own semiconductor factory at Glenrothes, Scotland. The company had about 35,000 employees. In 1967 Elliott Automation was merged into English Electric.[3]

Elliott Automation

Elliott Automation (as it had become) merged with English Electric in 1967. The data processing computer part of the company was merged with International Computers and Tabulators (ICT) in 1968; this marriage was forced by the British Government, who believed that the UK required a strong national computer company. The combined company was called International Computers Limited (ICL). The real-time computer part of Elliott Automation remained, and was renamed Marconi Elliott Computer Systems Limited in 1969 and GEC Computers Limited in 1972, and remained at the original Borehamwood research laboratories until the late 1990s. The agreement which governed the split of computer technologies between the two companies disallowed ICT from developing real-time computer systems and disallowed Elliott Automation from developing data processing computer systems for a few years after the split. The remainder of Elliott Automation which produced aircraft instruments and control systems, was retained by English Electric.

EASAMS

EASAMS was E A Space and Advanced Military Systems (the EA was never spelled out), based in Frimley, Surrey – first at the nearby Marconi Electronic Systems plant in Chobham Road and later, when it became a limited company, at its headquarters in Lyon Way. It evolved its proprietary EMPRENT, an early program evaluation and review technique (PERT) planning system used in building North Sea oil platforms, and for the BAC TSR-2. Developments for the cancelled TSR-2 were later incorporated into multirole combat aircraft (MRCA), which finally became the Panavia Tornado.

EASAMS senior management was highly conservative, and a number of innovative engineers working on 'private venture' projects such as Hierarchical Object-Oriented Design (HOOD) and Ada language development left to form their own firms. These included Admiral Computing (which later merged with Logica), Systems Designers Ltd (which later merged with Electronic Data Systems (EDS), and subsequently became part of Hewlett-Packard (HP)) and Software Sciences (later a part of IBM UK).

EASAMS Ltd was an independent company within General Electric Company (GEC), founded in 1962 to provide services in system design, operational research and project management. In the 1990s EASAMS became part of Marconi Electronic Systems before losing its identity.

Computers

The following computer models were produced:[4]

- Elliott 152 (1950)

- Elliott Nicholas (1952)

- Elliott/NRDC 401 (1953)[5][6][7][8] - prototype computer, installed in 1954 at Rothamsted Experimental Station[9][10][11][12]

- Elliott 153 (DF computer) (1954)

- Elliott/GCHQ OEDIPUS (311) (1954)

- TRIDAC (1954) three-dimensional analogue computer system for guided missile research, built for the Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough.

- Elliott 402 (1955)[13]

- Elliott 403 (WREDAC) (1955)[14]

- Elliott 405 (1956) (One donated by Nestle to The Forest School, Winnersh and named Nellie[15])

- Elliott 802[16][17][18] (1958–1961) 6 were sold

- Elliott 803 (1959) about 250 sold, mainly 803B

- 803A had 4 or 8 K of 39-bit words of memory and all internal data was held in one 102-bit long serial path.

- 803B had 4 or 8 K of 39-bit words of memory. The single data path was split into several shorter (48-bit long) serial paths to reduce instruction execution time. A hardware floating point option was available.

- Elliott ARCH 1000 (1962)

- Elliott 503 (1963) software compatible with 803

- Elliott 900 series (1963)

- For military customers there were four models of the 900 series: 920A, 920B, 920M and 920C. Only a few of the 920A were produced, rapidly obsoleted by the faster 920B. The 920M was a miniaturised version of the 920B. They were discrete transistor machines. The 920C was a later even faster derivative built using custom integrated circuits. All were shipped in robust "militarized" cases suitable for mounting in vehicles, ships and aircraft.

- Civilian customers were sold versions of the 920A, 920B and 920C called Elliott 920A, 903 and 905 respectively. These were shipped in desk sized cabinets suitable for use in an office or laboratory environment.

- Versions of the 920B and 920C for industrial automation were sold as Arch 900 and Arch900 respectively. These were shipped in industrial cabinets similar to those used for the civilian systems.

- The 903 [19] was a desk-sized machine popular with universities and colleges as a teaching machine, with small research laboratories as a scientific processor and also as a versatile system for use in industrial process control. It was typically equipped with 8 or 16K of core store and was predominantly a paper tape based machine but card readers, line printers, incremental graph plotters and magnetic tape systems were also available. The machine was usually programmed in symbolic assembly code, ALGOL or FORTRAN II.[20] The civilian 920C was the 905, also in a desk-sized configuration. Some 905s had fixed head disk systems attached. A FORTRAN IV system was provided for the 905.

- Elliott 502 (1964)

- One 502 used to generate simulated radar signals for training operators of Linesman/Mediator system.

- Elliott 4100 series (1966) A joint development with NCR Corporation. Elliott selling to the scientific market and NCR selling to the commercial market.[21][22] The 4100 series had a two accumulator architecture with 64 K (4120 model) or 256 K (4130 model) words of 24-bit memory, of either 2 or 6 microseconds cycle time.[23][24] The 4100 could have a 4180 graphics display terminal with light pen for input connected.[25]

See also

- BAE Systems Avionics

References

- ↑ The Emperor's Old Clothes)

- ↑ Simon Lavington, Moving Targets: Elliott-Automation and the Dawn of the Computer Age in Britain, 1947–67, Springer Science+Business Media, 2011 ISBN:1848829337 pages 13–17

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 http://rochesteravionicarchives.co.uk/about-us/history-elliott-brothers/ History of Elliott Brothers, retrieved 2017 Oct 12

- ↑ Elliott computer models

- ↑ "19. Elliott-N.R.D.C. Computer 401 Mk 1" (in en). Digital Computer Newsletter 5 (3): 8. 1953. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0694609.

- ↑ "Cleaning the Elliott 401 computer". https://blog.sciencemuseum.org.uk/cleaning-the-elliott-401-computer/.

- ↑ "Elliott: NRDC 401 Mk I mainframe". http://collection.sciencemuseum.org.uk/objects/co62354/elliott-nrdc-401-mk-i-mainframe-mainframe.

- ↑ Research, United States Office of Naval (1953) (in en). A survey of automatic digital computers. Office of Naval Research, Dept. of the Navy. p. 31. https://archive.org/details/bitsavers_onrASurveyomputers1953_8778395.

- ↑ "First electronic computer in civilian research | The Elliott 401 Computer at Rothamsted | Businesses, trades, employment | Topics - from Archaeology to Wartime | Harpenden History". http://www.harpenden-history.org.uk/page_id__343.aspx.

- ↑ Lipton, S. (1955). "A note on the electronic computer at Rothamsted". Mathematics of Computation 9 (50): 69–70. doi:10.1090/S0025-5718-1955-0069612-2. ISSN 0025-5718.

- ↑ "Mainframe group of early British-designed computers". http://www.ourcomputerheritage.org/maincomp.htm.

- ↑ "Technical details of Elliott 401 computer". Computer Conservation Society. https://ourcomputerheritage.org/Maincomp/Eli/ccs-e2x1.pdf.

- ↑ "Computers, Overseas: Elliott 402 Electronic Digital Computer" (in en). Digital Computer Newsletter 7 (2): 12–13. Apr 1955. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0694616.

- ↑ "Technical detaisl of Elliott 403". Computer Conservation Society. https://ourcomputerheritage.org/Maincomp/Eli/E2Extra403.pdf.

- ↑ Higgins, Chris (4 June 2017). "Watch Nellie, the British School Computer of 1969". Mental Floss. http://mentalfloss.com/article/501480/watch-nellie-british-school-computer-1969.

- ↑ "Reference Information: A Survey of British Digital Computers (Part 1)". Computers and Automation 8 (3): Elliott Brothers Ltd, Compo Mach. Div., Borehamwood, Hertfordsh (p. 26). Mar 1959. http://www.bitsavers.org/magazines/Computers_And_Automation/195903.pdf. Retrieved 5 September 2020.

- ↑ "Computers and Centers, Overseas: 1. Elliott Brothers, Ltd., Elliott 802, London, England" (in en). Digital Computer Newsletter 11 (1): 8. Jan 1959. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0694631.

- ↑ "Computers and Centers, Overseas: 1. Elliot Brothers Ltd., National-Elliot 802, London, England" (in en). Digital Computer Newsletter 11 (2): 8–9. Apr 1959. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/AD0694632.

- ↑ 903

- ↑ Elliott 900 Series Computers: Software and Documentation Archive

- ↑ "Systems architectures for the Elliott 4100 Series computers". ourcomputerheritage.org. November 2011. http://www.ourcomputerheritage.org/ccs-e6x2.pdf.

- ↑ "Introduction to 4100 Software". NCR ELLIOTT. July 1965. http://www.memtsi.dsi.uminho.pt/ocr/ncr_4100_software.pdf.

- ↑ "Systems architectures for the Elliott 4100 Series computers". November 2011. https://www.ourcomputerheritage.org/Maincomp/Eli/ccs-e6x2.pdf.

- ↑ "Instruction sets and instruction times for the Elliott 4100 Series computers". November 2011. https://www.ourcomputerheritage.org/Maincomp/Eli/ccs-e6x3.pdf.

- ↑ Brereton, O P (1978). "The Uses of Interactive Computer Graphics For Solving Differential Equations". pp. 16-21. https://eprints.keele.ac.uk/id/eprint/6797/1/BreretonPhD1978.pdf.

Further reading

- Simon Lavington, Moving Targets: Elliott-Automation and the Dawn of the Computer Age in Britain, 1947–67, Springer, 2011.

- Simon Lavington ed 'Alan Turing and his contemporaries: Building the world's first computers', BCS, 2012

External links

- Elliott Computers, Simon Lavington, The Bulletin of the Computer Conservation Society, Number 42, Spring 2008, ISSN 0958-7403

- "Our Computer Heritage". http://www.ourcomputerheritage.org/.

- Borehamwood, Staffordshire University

- 'Nellie' (Elliott 405) Artefact at The ICL Computer Museum

- Elliott Photo Gallery, Thinking Machine

|