Biology:Gonatus onyx

| Clawed armhook squid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Gonatus onyx on the Davidson Seamount at 1,328 m depth. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Mollusca |

| Class: | Cephalopoda |

| Order: | Oegopsida |

| Family: | Gonatidae |

| Genus: | Gonatus |

| Species: | G. onyx

|

| Binomial name | |

| Gonatus onyx Young, 1972[2]

| |

The Gonatus Onyx is in the class Cephalopoda, in the phylum Mollusca. It is also known as the Clawed arm hook squid or Black-eyed squid. It got these names from the characteristic black eye and from its two arms with clawed hooks on the end that extend a bit further than the other arms. It is a squid in the family Gonatidae, found most commonly in the northern Pacific Ocean from Japan to California. They are one of the most abundant cephalopods off the coast of California, mostly found at deeper depths, rising during the day most likely to feed.

The mantle size of the Gonatus Onyx has been known to reach up to 18cm. G. Onyx size varies from region to region, with larger members of the species being found in warmer areas.

The type specimen was collected off the coast of California and was deposited at the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.[3]

Range and habitat

G. Onyx is a very common cephalopod that is found in the Northern Pacific Ocean, ranging from coastal California to the east coast of Japan, and are found as far north as the Bering Sea. The adults and juveniles inhabit different areas, with the more solitary adults tending to like deeper water and the pack hunting juveniles preferring shallow coastal waters. They have one of the lowest seasonal variations over wide areas from the members of the family Gonatidae. The depth distribution is bimodal and follows a certain diel rhythm.[4] During the day they tend to stay at deeper depths with adults found from 400-1000m, with an average depth of around 700m. Younger members are found at 0-800m during the day with an average of around 400m.[5] During the night both adults and juveniles tend to rise from the deeper water. Adults at night have a range of depths from 100-800m with a large majority found around 400-500m. Juveniles have a smaller range from 0-500m and are more evenly spread out with most found from 0-300m.[6]

Description

The Gonatus Onyx or Black-eyed squid is a relatively smaller-sized squid with an average mantle length of about 12 cm, with some warmer water individuals reaching up to 18 cm. This species shows sexual dimorphism in mantle size with females maturing faster and growing a couple of cm larger than the males. The mantle makes up a majority of their body length, the arms make up another about 40mm on average. They have characteristic black eyes on either side of their head, these highly developed sensory organs are helpful for hunting in pitch black conditions. The armature consists of five pairs, one pair with a large primary hook at the end and multiple rows of suckers, the other four pairs are generally shorter and do not have this tentacular hook, still lined with rows of suckers. The use of clawed arms are thought to be used in hunting and for better catching and handling of their prey.[7] Some individuals are harder to identify as the tentacular club is very fragile and easily damaged. The mantle’s fins are smaller than the other members of Gonatids and the tail is less tapered. G. Onyx like most squid move using a propulsive force, using water expelled from a siphon with the combination of fin movements. The juvenile G. Onyx has been observed using ink as a defensive mechanism and as a propulsive force, while the adults rarely use ink and rather choose to use a faster propulsive force. Matured members possess chromatophores, specialized small organs under the skin of the squid, which are used to change colors to hide reflective internal organs. They have a beak, like all cephalopods; it is relatively small compared to other species. The upper part of the beak is sharp and has less curvature, while the bottom is curved, duller, and shorter. This specialized beak makes it easier for squid to attack prey larger than themselves.[7]

Reproduction and spawning

G. Onyx like most cephalopods are oviparous. Fertilization is external in squids, males use specialized arms to transfer packages of sperm, spermatophores, that are transferred to a female’s seminal receptacle, a specialized internal oviduct near the female’s mouth. Unlike other species of cephalopods, females then lay eggs in egg masses; these masses are composed of two thin membranes. The membranes form chambers holding individual eggs that are arranged in honeycomb-like patterns. Membranes are fused with each individual chamber; this is the reason the egg mass is held together in a random orientation. This egg mass is dark black and there is a thin layer of greyish black membrane over the thinner sections of egg chambers. Each individual egg inside the mass are ovoid in shape, they range in size from 2.0 mm to 3.0 mm in length, and 1.8 mm to 2.1 mm in width. The egg mass can contain approximately 2000 hatchlings. Each female and male can reproduce once in their lifetime as both genders die after reproduction. Female G. Onyx are relatively unique as they hold the egg mass with their clawed arms. The females lose their normal arms after fertilization from the inability to feed while holding their eggs. Females migrate to deep water (1250 m – 1750 m) once they lay their egg masses, this is a strategy to minimize the chance of encountering a predator. They can hold these egg sacks for up to nine months as they develop, going this entire time living off of built-up lipids inside the digestive gland.[6]

Early life and behavior

The hatchling’s physiology is very different from mature individuals. Hatching specimens collected were found to be moderately large at a total length of 5.0mm. The mantle length of these hatchlings ranged from 3.2mm-3.5mm and the width was 50-60% of the mantle length. Arms and tentacles are very different, there are 4 pairs of arms that are about 18-20% of the mantle size. Arm pairs 1 and 2 have suckers and sucker buds, arm pairs 3 and 4 lack suckers. There are one pair of tentacles that are proportionally larger than the arm pairs at around 40% of mantle length on average, they both contain a large number of sucker buds and the central hook is not yet visible. Hatchlings can be identified by a characteristic chromatophore pattern, with 5-6 in a single row on the aboral surface of the tentacles, a single pair on the base of the fins on the dorsal mantle, a single pair at the anterior end of the hatching gland on the mid-dorsal mantle, and 2-3 pairs on the lateral mantle. Hatchlings move with the hop-and-sink swimming style. Hatchlings mature into juveniles in about 3 months and are very active schooling predators during this time, they develop their hooks on arms and tentacles. Juveniles tend to school because they have less of a tendency to go after members of the same species when they are not fully developed. They are still relatively small with a dorsal mantle length of 30mm on average. Juveniles quickly accumulate lipids to prepare for reproduction, however, the exact reason for schooling is unknown.[8]

Adult life and behavior

Individuals older than about 3 months move to deeper waters and change their entire lifestyle. Older G. Onyx are solitary hunters and make long vertical migrations during the night, they move closer to the surface to feed on other organisms that follow the same migration. Adults of this species have been known to be cannibalistic, with some studies indicating a rate as high as 42% of prey being of the same species. This cannibalistic behavior could serve as a reason for the more solitary behavior. Other prey tends to be fish that are around the same size as the individual, the prey is mostly composed of Stenobrachius leucopsarus. The diet of juveniles is largely unknown with some studies finding a predominant crustacean diet and then a shift to nekton when mature.[9]

References

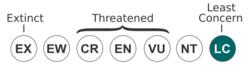

- ↑ Barratt, I.; Allcock, L. (2014). "Gonatus onyx". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T162950A957015. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T162950A957015.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/162950/957015. Retrieved 18 November 2021.

- ↑ Julian Finn (2016). "Gonatus onyx Young, 1972". World Register of Marine Species. Flanders Marine Institute. http://www.marinespecies.org/aphia.php?p=taxdetails&id=341859.

- ↑ Current Classification of Recent Cephalopoda

- ↑ Watanabe, Hikaru; Kubodera, Tsunemi; Moku, Masatoshi; Kawaguchi, Kouichi (2006-06-13). "Diel vertical migration of squid in the warm core ring and cold water masses in the transition region of the western North Pacific" (in en). Marine Ecology Progress Series 315: 187–197. doi:10.3354/meps315187. ISSN 0171-8630. https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v315/p187-197/.

- ↑ admin (2020-03-17). Running the gauntlet— Deep-sea animals face multiple dangers in their daily migration. http://119.78.100.173/C666//handle/2XK7JSWQ/245848.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hunt, J. C.; Seibel, B. A. (2000-04-01). "Life history of Gonatus onyx (Cephalopoda: Teuthoidea): ontogenetic changes in habitat, behavior and physiology" (in en). Marine Biology 136 (3): 543–552. doi:10.1007/s002270050714. ISSN 1432-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270050714.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hunt, J. C.; Seibel, B. A. (2000-04-01). "Life history of Gonatus onyx (Cephalopoda: Teuthoidea): ontogenetic changes in habitat, behavior and physiology" (in en). Marine Biology 136 (3): 543–552. doi:10.1007/s002270050714. ISSN 1432-1793. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002270050714.

- ↑ "Advances in Marine Biology", Advances in Marine Biology Volume 60, Advances in Marine Biology, 60, Elsevier, 2011, pp. iii, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-385529-9.00007-x, ISBN 9780123855299, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-385529-9.00007-x, retrieved 2022-04-22

- ↑ Hoving, H.J.T.; Robison, B.H. (2016). "Deep-sea in situ observations of gonatid squid and their prey reveal high occurrence of cannibalism". Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 116: 94–98. doi:10.1016/j.dsr.2016.08.001. ISSN 0967-0637. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2016.08.001.

External links

- "CephBase: Gonatus onyx". Archived from the original on 2005. https://web.archive.org/web/20050817053958/http://www.cephbase.utmb.edu/spdb/speciesc.cfm?CephID=323.

- Tree of Life web project: Gonatus onyx

- [1]

Wikidata ☰ Q2461048 entry